CliFin: Investing in Sustainable Real Estate

By Angelique Nivet

Real Estate and Climate Change

Real Estate’s Impact on Climate Change and the Environment

The building industry accounts for a considerable consumption of energy and resources, making it a top polluting sector (Gonçalves, “Green Buildings Are More Ecological and Cost-Effective”). The construction, occupation, and use of buildings, notably as regards heat, water, and light, call for innovative and sustainable strategies to help reduce real estate’s environmental impact. In 2018, buildings accounted for 3.101 million tons of oil equivalent of final energy consumption on a global scale (AIM, “Sustainable Impact Investing in Real Estate: An Investor’s View”). This represents 31% of total final energy consumption. According to the 2020 Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction, the operation of buildings accounts for 28% of total energy-related CO2 emissions globally (UNEP FI, “Responsible Property Investment”). This number rises to 38% when considering emissions from the construction industry. In the United States alone, building operations are the source of roughly 40% of all energy consumption (Sisson, “As Risks of Climate Change Rise, Investors Seek Greener Buildings”). The intensive energy use generated by buildings is thus responsible for a high portion of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. This, coupled with population growth and rising urbanization, stresses the need to decarbonize the real estate sector if we are to effectively transition to a low-carbon economy (AIM, “Sustainable Impact Investing in Real Estate: An Investor’s View). Buildings offer the largest cost-effective GHG mitigation potential as well as attractive economic gains through the implementation of sustainable design and technologies (UNEP FI, “Responsible Property Investment”).

In the United States alone, building operations are the source of roughly 40% of all energy consumption

In recent years, the perception of risk associated with climate change has prompted investors to steer money towards higher-performing green assets. New standards and measurement tools have empowered such investors to raise the bar both for environmental and economic performance. This rise in awareness as regards climate change’s impact on real estate is fueled by the ever-increasing frequency of natural disasters such as Hurricane Ida which caused an estimated $27 billion to $40 billion in property damage in late August and early September 2021 (Sisson, “As Risks of Climate Change Rise, Investors Seek Greener Buildings”). In the last four decades, the frequency of natural disasters recorded in the Emergency Events Database has increased almost three-fold (ADB, “Global Increase in Climate-Related Disasters”). Consequently, it is not surprising 88% of large companies have had a physical asset affected by extreme weather according to Cervest, an A.I. platform which assesses corporate climate risk (Sisson, “As Risks of Climate Change Rise, Investors Seek Greener Buildings”). Real estate’s significant environmental footprint coupled with the realization of climate change’s growing impact on the sector has altered the strategies and objectives of key financial players that now seek more transparency and long-term risk assessments. For example, the Canadian real estate firm Ivanhoe Cambridge has linked $6.87 billion of its debt to the environmental performance of its portfolio. Crucially, a robust motivational driver for companies lies in the fact that hitting sustainability goals means paying less interest (Sisson, “As Risks of Climate Change Rise, Investors Seek Greener Buildings”).

CliFin and Sustainable Real Estate Investment

‘CliFin’ or Climate Finance refers to any financial service, instrument, vehicle, or regulation designed to bring about climate change mitigation or adaptation (Tan Bhala & Wilkinson, “CliFin: Climate Finance to Avoid Climategeddon”). According to this perspective, sustainable real estate investment can be considered a powerful and dynamic CliFin tool. In 2025 for example, the developer Lendlease is expected to open a $600 million eco-efficient residential and office complex in Los Angeles. The latter will display the typical hallmarks of sustainable living including an all-electric residential tower, solar panels, proximity to a light-rail stop, and a pedestrian plaza (Sisson, “As Risks of Climate Change Rise, Investors Seek Greener Buildings”). Here, sustainability represents a core feature of the development’s financing plan rather than a mere token of corporate responsibility (Sisson, “As Risks of Climate Change Rise, Investors Seek Greener Buildings”). Lendlease forms part of a broader movement of investors steering money towards sustainable real estate as new standards and technology allow for better monitoring of a development’s carbon footprint. Other big players worth mentioning include Hudson Pacific Properties, the owner of Epic, a Hollywood solar-paneled office tower occupied by Netflix, and the international industrial giant Prologis which sells green bonds that fund the construction of sustainable warehouses (Sisson, “As Risks of Climate Change Rise, Investors Seek Greener Buildings”).

Sustainable real estate is nevertheless not a new concept. For nearly three decades, the Green Building Council has promoted eco-friendly pathways through its standard for building sustainability LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design). By increasingly betting on sustainable real estate, developers seek to tap the growing hunger for investing focused on Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) criteria. This trend is channeling significant capital: in 2020, mutual funds and exchange-traded funds had already invested close to $300 billion in sustainable assets globally (Sisson, “As Risks of Climate Change Rise, Investors Seek Greener Buildings”). Developments such as Lendlease’s Los Angeles project also aim to appeal to a high-end clientele while getting ahead of regulation to create more valuable assets, attracting more investors in the process. In April the global investment management firm Invesco launched an exchange-traded fund for green buildings. Meanwhile, a similar green real estate fund started by Foresight last year has already shown double-digit returns (Sisson, “As Risks of Climate Change Rise, Investors Seek Greener Buildings”).

Investing in Sustainable Real Estate

ESG and Impact Funds

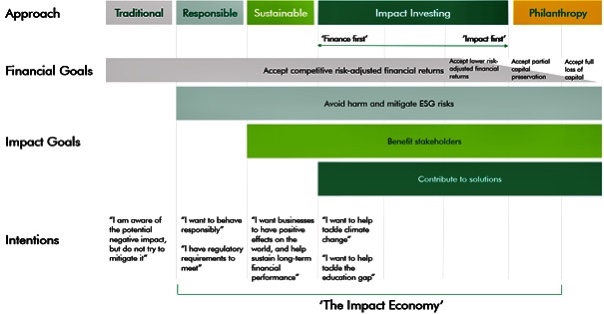

ESG funds and impact funds both focus on the three key Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) objectives. If ESG funds seek to promote ESG characteristics, however, such goals are fully embedded in the overall investment strategy of impact funds (Impact Investing Institute). Impact investments can thus be defined as investments designed to generate a positive and measurable social, governance and environmental impact alongside a financial return (Global Impact Investing Network – GIIN). Moreover, an investment can be considered ‘green’ if it fosters energy efficiency and the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions (Robins & Sweatman, “Green Tagging: Mobilising Bank Finance for Energy Efficiency in Real Estate”). In the real estate sector, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set by the United Nations importantly provide high-level global ESG guidelines. In addition, to prevent green washing at the European level the European Commission has launched the Sustainable Financial Disclosure Regulations (SFDR) which outline actions for disclosure of sustainability targets as well as reporting mechanisms (INREV).

In Focus: BNP Paribas REIM’s Impact Fund

BNP Paribas’s Real Estate Investment Management (REIM) branch recently launched the first real estate impact fund in Europe that aims to comply with the 2015 Paris Agreement’s objective to reduce carbon emissions by 40% (BNP Paribas Real Estate, “BNP Paribas Reim Launches New Climate Impact Fund in Europe”). The European Impact Property Fund (EIPF) illustrates the drive in the real estate sector to implement effective sustainable transition solutions. Importantly, the EIPF seeks to refurbish and bring buildings up to date with the energy-efficient technology, equipment, and regulations of today by adopting a threefold pathway: investing in buildings, involving all stakeholders of the value chain, and optimizing operating expenses. BNP Paribas’s EIPF further aims to inspire other institutional investors in Europe and Asia who recognize real estate’s role in the reduction of energy and carbon emissions. BNP Paribas REIM is one of the first European real estate companies to publish an annual ESG report and to receive a green award for one of the best green office funds in Europe.

Attractions, Benefits, and Challenges For Investors and Fund Managers

Like most investments, sustainable development initiatives seek out effective, profitable, and easy-to-implement business models (Gonçalves, “Green Buildings Are More Ecological and Cost-Effective”). Not only does the real estate sector play a pivotal role in the transition to a low-carbon economy, but the sector also has a high potential to positively impact both the environment and society. Positive environmental impacts stem from performance of the buildings such as their energy efficiency, whether they have been set up with grey or rainwater recycling systems, their waste management solutions, and whether they display cyclist facilities. In turn, social impacts stem from the purpose of the buildings, for example, schools, hospitals, and community buildings (AIM, “Sustainable Impact Investing in Real Estate: An Investor’s View).

If ESG investments in the real estate sector face several challenges such as the lack of common guidelines and technology as well as a fear of ‘green washing’, their benefits seem to largely outweigh the costs (Sisson, “As Risks of Climate Change Rise, Investors Seek Greener Buildings”). ESG investment strategies, indeed, have proved to help investors gravitate towards stronger, more profitable assets. According to a study of London office space by JLL, sustainable buildings attract higher-quality tenants and allow for higher rent of up to 10% more (JLL, “The Impact of Sustainability on Value in Central London”). New technology makes it increasingly easier for asset managers and investors to compare portfolio performance but also to evaluate and retrofit existing buildings. Not betting on sustainability entails higher costs in the long run as buildings that fail to lower their carbon footprint in the future will likely depreciate in value (Sisson, “As Risks of Climate Change Rise, Investors Seek Greener Buildings”).

Green Buildings

What Are ‘Green Buildings’?

Green buildings are characterized by their efficient lighting, heating, plumbing, and insulation systems. Further key characteristics include renewable energy generators such as photovoltaic panels, sustainable waste management, eco-friendly building materials and a reduction of volatile organic compounds (VOC) emissions (Gonçalves, “Green Buildings Are More Ecological and Cost-Effective”). Strict labels are used to certify infrastructure designed in accordance with the green building criteria such as the BREEAM (Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method) label and Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) ratings in the United Kingdom, and the LEED in the United States.

Ecological and Financial Benefits of Green Buildings

Green buildings tend to boost property values in the long term. On average, certified green buildings have a higher occupancy rate than non-certified buildings. This corresponds to a 4% increase for LEED-certified buildings and a 9.5% increase for office buildings (Gonçalves, “Green Buildings Are More Ecological and Cost-Effective”). Certified buildings are thus easier to rent and stay less idle which reduces operational costs. In addition to their higher rental price, the resale value of certified buildings is worth 8 to 10% more compared to the original property value (Gonçalves, “Green Buildings Are More Ecological and Cost-Effective”). Certified sustainable buildings promote lower maintenance costs through their smarter use of energy and resources. According to the World Green Building Council, green buildings allow for 25% to 35% of energy savings and up to 39% of water savings compared to conventional buildings (World Green Building Council, “World Green Building Council Annual Report 2020”). A major obstacle facing the green building industry is the overestimation of its costs. More than 60% of people believe the cost of green buildings is considerably higher than conventional buildings (Hamad, “Is It Affordable to Build Green?”). The U.S. Green Building Council challenges this misconception and reports the cost of a green building is on average only 2% higher than its non-green counterpart (Knox, “Green building costs and savings”).

Case Studies

Located in the British town of Milton Keynes, Magnitude 314 is a logistics warehouse designed to WELL principles that has achieved both a BREEAM 2014 Excellent and EPC A rating. The WELL Building Standard identifies seven concepts that comprehensively address not only the design and operations of buildings, but also how they affect human behaviors related to health and well-being (International WELL Building Institute). The seven concepts are: air, water, nourishment, light, fitness, comfort, and mind. Magnitude 314 is also the world’s first Net Zero Carbon for Construction verified building, in line with the UKGBC Net Zero Carbon Buildings Framework Definition (Chetwoods, “Magnitude 314”). The building’s design has resulted in a 25.8% reduction in embodied carbon compared to a standard logistics warehouse (UKGBC, “Case Study: Magnitude 314”). A key consideration during the construction period was the building’s structural capacity to allow for solar photovoltaic panels on the roof once occupied. After the embodied carbon of the building was effectively reduced, the next step was to offset any remaining carbon using the Gold Standard for carbon offsets. The carbon offsets for Magnitude 314 represent an estimated $2 million of wider value to society, including 12,000 mangrove trees planted in Mozambique and Madagascar (UKGBC, “Case Study: Magnitude 314”). In addition, the warehouse’s innovative design tested principles of grid-based modular systems and standardization to improve elevations and interiors, reduce waste, facilitate construction, as well as maximize efficiency and flexibility (Chetwoods, “Magnitude 314”).

Vertical is a pioneer development located in Amsterdam’s Sloterdijk-Centrum which consists of 168 owner-occupied homes spread over three sub-areas: West, East, and Center. Vertical’s construction started in 2020, drawing inspiration from different greeneries that harmoniously matched the surrounding Bretten landscape (Amsterdam Vertical). The development’s three sub-areas each focus on different sustainability goals, most notably preserving biodiversity. ‘Sustainable by default’, Vertical uses wind, sun, and geothermal heat for power (Amsterdam Vertical). Water is efficiently used, and rainwater recycled while gardens and green façades populate the structure, providing habitat space for local fauna while naturally cooling the buildings. Several of the habitations have furthermore been designed for professionals working from home to minimize commutes (Iamsterdam, “Six sustainable buildings changing the way Amsterdammers live, work and play”). Vertical has its own heat and cold storages, solar panels, bicycle facilities and a supply of electric cars in the garage. By extending the biodiversity of the Bretten landscape in its facades and roof gardens, Vertical increases the nesting opportunities and food supplies for birds and insects. A connector rather than an obstacle, Vertical aims to show that buildings can positively connect with their natural environment and become active enablers of change (Amsterdam Vertical).

Seattle’s Bullitt Center is a commercial office building opened on Earth Day in 2013. The first heavy-timber office building in Seattle since the early twentieth century, it is the first commercial building in the United States to earn Forest Stewardship Council Project Certification. The Bullitt Center is designed to use just a third of the energy consumed by a typical office building its size (Llanos, “Could this $30 million green tower be the future of world cities?”). In addition to the building’s central features which include radiant heating, composting toilets, rainwater harvesting, bike racks instead of car parking and an active design which promotes the use of stairs, the Bullitt Center highlights that it is possible to build entirely with responsibly sourced wood. Wood was a construction material of choice not only because of its natural beauty and strength but also because of its renewability and ability to imprison carbon through the lifespan of the building, designed to last 250 years (Bullitt Center). Interestingly, the Bullitt Center’s eco-friendly features are both structural and behavioral as tenants must commit to using only computers and electronic devices with high energy efficiency and to shut them down at night (Kaye, “Seattle’s Bullitt Center is set to push the boundaries of green building”).

Conclusions and Future Challenges

Covid-19 Disruptions and Responses

The Covid-19 pandemic has brought both new challenges and opportunities to the sustainable real estate sector. Some governments have notably chosen to tie recovery packages to improved climate change mitigation and adaptation measures. This was the case in Canada where state-backed loans and funding were offered to companies on the basis that they commit to future climate disclosures and environmental sustainability objectives (AIM, “Sustainable Impact Investing in Real Estate: An Investor’s View). There is hope the economic recovery following the pandemic will drive further green real estate incentives and eco-efficient building projects to be financed under sustainable investing.

Regulation, Sustainability Objectives and Emerging Key Issues

The adoption of new regulation may also play a role, with key past examples setting the tone such as New York’s 2019 law requiring building owners to reduce their carbon footprint and a similar law recently passed in Massachusetts (Sisson, “As Risks of Climate Change Rise, Investors Seek Greener Buildings”). To tackle the challenges that lie ahead of sustainable real estate investment, it is crucial to facilitate widespread access to essential information and to promote voluntary best practices among the real estate investment community. In this perspective, investors and real estate professionals must be handed the necessary tools to apply and integrate ESG criteria into their decision-making. It is also important to collect evidence highlighting the positive impact of sustainable property investments as they create environmental and social goods while increasing financial performance throughout the lifecycle of buildings (UNEP FI, “Responsible Property Investment”). Lastly, the shaping of bold policy and regulatory frameworks is necessary to durably implement low-carbon, climate-resilient building habits on a global scale (UNEP FI, “Responsible Property Investment”).

References

Amsterdam Vertical. https://www.amsterdamvertical.com/.

“BNP Paribas Reim Launches New Climate Impact Fund in Europe.” BNP Paribas Real Estate, Jan. 2021, www.realestate.bnpparibas.com/bnp-paribas-reim-launches-new-climate-impact-fund-europe.

Bullitt Center. https://bullittcenter.org/.

Global Impact Investing Network. https://thegiin.org/.

“Global Increase in Climate-Related Disasters.” ADB, Nov. 2015, Working Paper, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/global-increase-climate-related-disasters.pdf.

Gonçalves, André. “Green Buildings Are More Ecological and Cost-Effective.” Youmatter, Dec. 2019, youmatter.world/en/green-buildings-are-more-ecological-and-cost-effective/.

Hamad, Samar. “Is It Affordable to Build Green?”. The Sustainabilist, May 2020, https://thesustainabilist.ae/is-it-affordable-to-build-green/.

Impact Investing Institute. https://www.impactinvest.org.uk/.

INREV. https://www.inrev.org/.

International WELL Building Institute. https://legacy.wellcertified.com/en/explore-standard.

Kaye, Leon. “Seattle’s Bullitt Center is set to push the boundaries of green building.” The Guardian, Sept. 2011,https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/seattle-bullitt-center-green-sustainable-building?newsfeed=true.

Knox, Nora. “Green building costs and savings.” U.S. Green Building Council, March 2015, https://www.usgbc.org/articles/green-building-costs-and-savings.

Llanos, Miguel. “Could this $30 million green tower be the future of world cities?”. MSNBC, March 2012, https://web.archive.org/web/20120321121913/http:/usnews.msnbc.msn.com/_news/2012/03/20/10226909-could-this-30-million-green-tower-be-the-future-of-world-cities.

“Magnitude 314”, Chetwoods. https://www.chetwoods.com/projects/magnitude-314/.

Tan Bhala, Kara, and Tom Wilkinson. “CliFin: Climate Finance to Avoid Climategeddon.” Seven Pillars Institute, July 2019. https://sevenpillarsinstitute.org/clifin-climate-finance-to-avoid-climategeddon/.

“The Impact of Sustainability on Value in Central London.” JLL, May 2020, www.jll.co.uk/en/trends-and-insights/research/the-impact-of-sustainability-on-value.

“Case Study: Magnitude 314.” UKGBC. https://www.ukgbc.org/solutions/magnitude-314/.

“Responsible Property Investment – United Nations Environment – Finance Initiative.” UNEP FI, Aug. 2021, www.unepfi.org/investment/property/.

Robins, Nick, and Peter Sweatman. “Green Tagging: Mobilising Bank Finance for Energy Efficiency in Real Estate.” Report from the Bank Working Group 2017, Green Finance Platform, Dec. 2017, https://www.greenfinanceplatform.org/research/green-tagging-mobilising-bank-finance-energy-efficiency-real-estate.

Sisson, Patrick. “As Risks of Climate Change Rise, Investors Seek Greener Buildings.” The New York Times, Oct. 2021, www.nytimes.com/2021/10/26/business/climate-change-sustainable-real-estate.html.

“Six sustainable buildings changing the way Amsterdammers live, work and play.” Iamsterdam, Feb. 2019, https://www.iamsterdam.com/en/business/news-and-insights/news/2019/six-sustainable-buildings-in-amsterdam.

“Sustainable Impact Investing in Real Estate: An Investor’s View.” AIM, Nov. 2020, affirmativeim.com/sustainable-impact-investing-in-real-estate-an-investors-view/.

“World Green Building Council Annual Report 2020.” World Green Building Council, 2020, worldgbc.org/news-media/annual-report-2020.

“2020 Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction.” Globalabc, 2020, globalabc.org/resources/publications/2020-global-status-report-buildings-and-construction.