CliFin: Climate Finance to Avoid Climategeddon

By Kara Tan Bhala and Tom Wilkinson

The world is probably on the brink of climate change catastrophe. Financial institutions must eventually be part of the solution rather than enablers of the problem. CliFin, or climate finance, refers to any financial service, instrument, vehicle, or regulation designed to mitigate, or adapt to, the effects of climate change.

It appears legislative bodies are finally moving to take dedicated climate change action, due in no small measure to recent research. In 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) published a special report predicting the ecological effects of human activity. In this report, the IPCC finds that ecosystems have already been altered by climatic change. If global temperature rise continues at its current rate, the planet will be 1.5ºC warmer than pre-industrial levels between 2030 and 2052 (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, “Executive Summary”). With predictions like these, what can the financial world do to mitigate climate change?

Climate Change: Background

Scientists in the 19thcentury carried out some of the earliest research in the field. The work of individuals such as Joseph Fourier (who discovered the ‘greenhouse effect’) and John Tyndall (proposed the disproportionate influence of molecules such as carbon dioxide on global temperature) is crucial to the field. Modern climate science owes much to these early works, but one of the most influential studies was the 1967 work of Syukuro Manabe and Richard T. Wetherald, entitled “Thermal Equilibrium of the Atmosphere with a Given Distribution of Relative Humidity”. This study lays the foundation for many modern climate studies, and is the first to utilise predictive modelling to determine what influence human activity had, and would continue to have, upon climatic conditions. This study is so significant, that it occupies the top spot in CarbonBrief’s analysis of influential climate science papers (CarbonBrief, “The Most Influential Climate Change Papers of All Time”).

The Influence of Carbon Dioxide

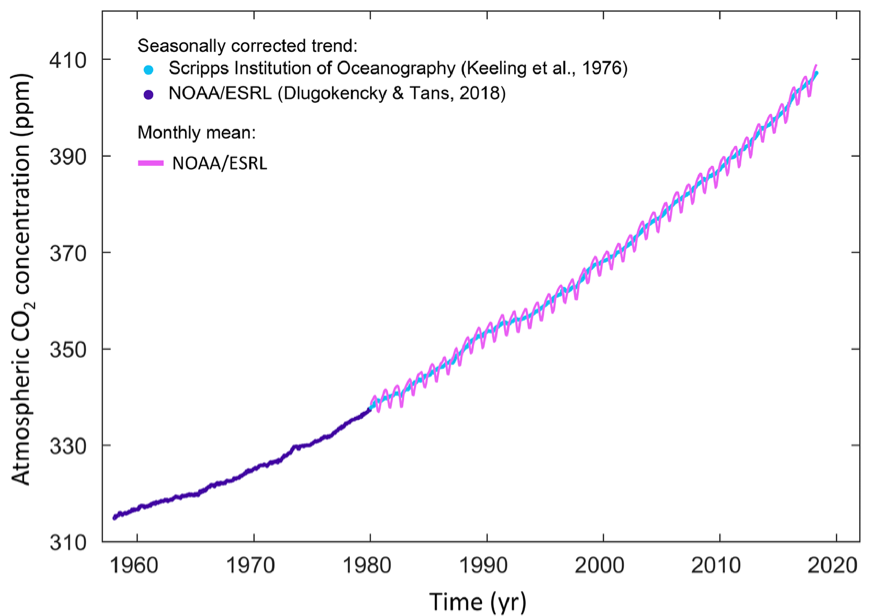

Greenhouse gases are the main drivers of climate change. There are multiple greenhouse gases, each emitted from human activity and from natural sources. Of these gases, carbon dioxide is the most important. Human activity over the past 250 years has drastically increased the amount of CO2being emitted per year. Prior to the Industrial Revolution, CO2concentration in the atmosphere was roughly 227 parts per million. By 2017, these levels had almost doubled, reaching 405 parts per million (Le Quéré et al., 2143). This immense increase is forecast to grow further if no action is taken.

(Le Quéré et al., 2018)

Human activity has tapped into multiple sources of CO2, but the biggest contributor to atmospheric increases is the combustion of fossil fuels. Through the burning of coal and other fossil fuels, carbon trapped centuries ago is combined with oxygen and released into the atmosphere. Once it is in the atmosphere, there are only four ways in which it is removed;

1. It reaches its ‘natural lifespan’ of 100 years, and subsequently breaks apart.

2. Reforestation occurs, and these new ‘carbon sinks’ absorbs excess CO2.

3. Oceans absorb CO2 and the gas undergoes dissolution.

4. Oceans absorb CO2 and the gas becomes a carbonate precipitate on the seafloor.

Each of these CO2 breakdowns has negative effects. Once CO2 reaches the atmosphere, it contributes to the ‘greenhouse effect’, trapping solar energy within the atmosphere. This increased solar energy subsequently causes temperatures to rise, with follow-on effects: ocean absorption of some of this heat energy warms the water, leading to the death of wildlife and atmospheric increases lead to degradation of environmental conditions and increased aridity. The one-hundred-year lifespan of a CO2 molecule means that emissions from today will influence the greenhouse effect in the early 22nd century.

Reforestation, while a possible solution to climate change, is likely to adversely impact human life and activity. The amount of reforestation to reverse CO2 to pre-Industrial Revolution levels comes at the cost of less living space. This potentially means removing established human settlements to regain land for forests. While there may be some who feel the ends justify the means, convincing those affected by reforestation will be arduous and may ultimately require the use of force.

CO2 absorption by the ocean creates problems with ocean acidity. More CO2 in the ocean changes the chemical composition of the seafloor (with a negative effect on sea life).

Impact of Climate Change

The effects of climate change are already visible, and have been for many years. One major impact is the increased frequency (and intensity) of extreme weather events. The widespread wildfires in California in 2018 are an example, as are the intense tropical storms which struck the Atlantic coast earlier in the same year. Climatic effects are also causing damage to the planet’s poles. One of the most memorable images of climate change in recent years was on the front cover of the Time Magazine in 2006. The cover, reproduced below, is a visceral reminder that climate change will affect global ecosystems in drastic ways.

More recent developments drive home just how dire the climate situation has become. In July of 2017, an iceberg twice as big as Luxembourg broke off the West Antarctic Ice Shelf (The Guardian, “Iceberg Twice Size of Luxembourg breaks off Antarctic Ice Shelf”). While icebergs break off of shelves in Antarctica fairly regularly, they are not usually the size of a European nation. Early in 2018, reports emerged that the Great Barrier Reef was dying off (The Atlantic, “Since 2016, Half of All Coral in the Great Barrier Reef Has Died”). The major cause of this destruction is the growing increase in ocean temperature throughout the world, as the ocean attempts to absorb the extra solar energy being trapped by the greenhouse effect. As soon warm water strikes the Great Barrier Reef, coral starts dying out (some, in fact, die instantly). Further increases in ocean temperature, which have been predicted, will likely kill off coral reefs throughout worldwide.

CliFin: Financial Impact of Climate Change

While the environmental effects of climate change are well documented, the financial consequences tend to be overlooked. Ongoing climatic change has major implications for the financial world. Three main areas of risk are of concern (Carney, “A Transition in Thinking and Action”). The physical impacts of climate change have increased in magnitude for some time. While the environmental cost is enormous, financial costs also will continue to mount. Between 1980 and 2017, the economic losses related to weather events have more than tripled. In 2017 alone, weather-related financial losses were around US$130 billion. (Carney, “A Transition in Thinking and Action”). With the expected increase in severe weather events associated with climate change, these costs will grow. It stands to reason that longer-term climatic shifts will result in increased costs throughout various industries. For example, increased aridity or decreased rainfall from global temperature increases will subsequently lead to increased costs for the agricultural sector. This extra expense makes the sector less attractive to investors, decreasing capital available to those trying to improve crop growing conditions.

The second set of CliFin risks focus on the liability of climate change. With climate change threatening communities worldwide, affected groups will seek compensation for environmental damage climate change has caused (Bank of England, “Enhancing Banks’ and Insurers’ Approaches To Managing The Financial Risks from Climate Change”). In order to do so, questions need to be asked, such as:

- Who is responsible for climate change?

- How far back should a company’s impact on climate be measured? (i.e. should older companies, which have been emitting longer, shoulder a greater share of the blame?)

- Are national entities (for example, state-owned enterprises) to face the same repercussions?

- Do investors bear responsibility for climate issues?

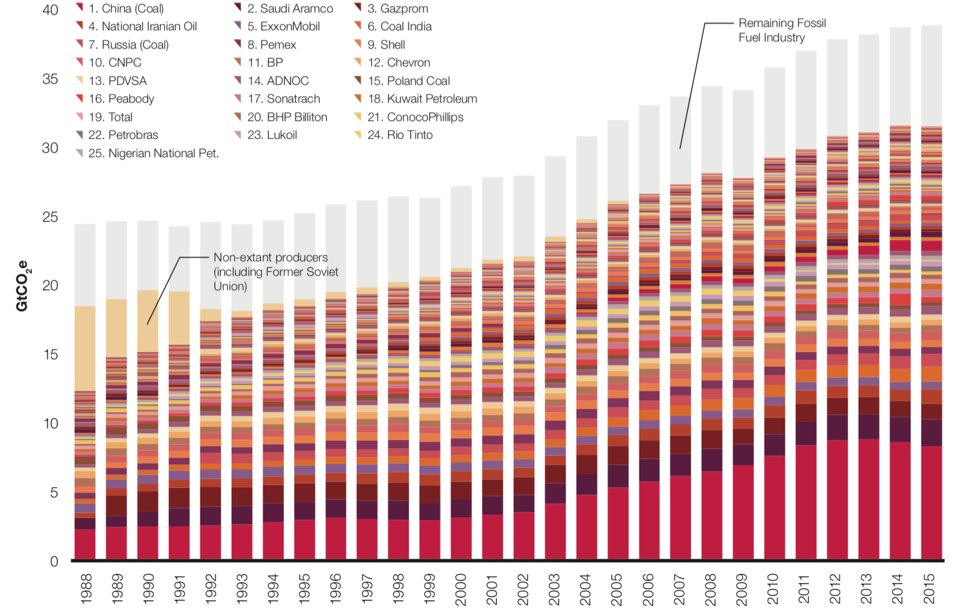

The main responsibility for increased CO2 emissions over the past 250 years lies with large corporations and state-owned enterprises. The graph below, reproduced from the 2017 Carbon Majors Report, shows the greenhouse gas emissions of the top 100 active fossil fuel producing entities. It is worth noting that some of the largest emitters are state-owned corporations, or those with significant government investment, which leads back to the question of liability. Compared to this, the carbon footprint of any individual person is incredibly low.

(Carbon Disclosure Project, 2017)

Some of the questions raised by the issue of liability are not easy to answer. For example, while it may be tempting to blame investors for continuing to fund large CO2 emitters, in some cases it may not be obvious to the investor that her actions encourage this action. Many corporations are not required to disclose the effects their actions have on the environment, and arguably, investors who do not have this information cannot be held accountable for resulting climate related problems. Other concerns point to the lack of a major framework or minimum standards for climate-related disclosures (Financial Conduct Authority, “Climate Change and Green Finance”).

Carney identifies a third financial risk: ‘transition’ risks. This term refers to the risks associated with the shift towards a low-carbon economy. First, the transition to low-carbon economies must occur earlier, rather than later because the worst effects of climate change will not be felt for some years. It is precisely because of the future-focused nature of climate change that there is minimal incentive for change in the present. Shifting to a low-carbon system will be costly, and its curative effects will not be felt for immediately. Another major risk raises concerns of a successful transition to a low-carbon economy being negative for wider financial markets. For example, if large firms were forced to re-evaluate the risks posed by climate change, it could subsequently deter investors from providing capital to mitigate the challenges. This, in turn, could cause greater losses, and to quote Mark Carney, result in a “climate Minsky moment”. As such, it is important to effectively manage the shift to a low-carbon economy, ensuring it occurs within decent regulatory and financial frameworks.

CliFin: Financial Mitigation of Climate Change

With limited methods to remove CO2 from the atmosphere, current management strategies rely on reducing the quantities being emitted, or financially penalising large emitters. There are multiple paths to achieve these objectives within current financial frameworks. While doing nothing is another possibility, and saves money in the short term, many industries will suffer as a result of climate change. The social and economic effects of climate change make this choice the least ethical option.

The purchasing of so-called ‘carbon credits’ is currently one of the major strategies to minimise the effects of climate change. The carbon credit system relies on setting a fixed price on CO2 emissions. A large number of credits are subsequently purchased to offset the emissions generated by the actions of the purchaser, and in doing so is supposed to fulfil corporate obligations to mitigate climate change. While this system has been in place for some time, it does not necessarily present the best way forward.

The system seems to be inherently short-term in nature. Rather than actually addressing the emissions, it places a financial penalty upon it, akin to a fine or a tax. There are arguments both for and against the system. On the plus side, it helps to preserve corporate freedom, and minimises government interference in private business. On the minus column, it is a system that favours entities with economic means. It is much easier for a large petrochemical corporation to pay for its emissions than a local or national producer, for example. This system has also created a financial industry surrounding the purchasing and trading of carbon credits. As the transition to a low-carbon economy occurs, this entire industry is placed at risk. To some, this would raise an ethical conundrum: is the destruction of a financial sector justified, in order to prevent global climatic change?

Carbon credits are not the only CliFin solution currently in practice. There are many corporations taking some moral responsibility for emissions, and in doing so they seek to minimise or mitigate their contributions to climate change through their own actions. In New Zealand, one of the major petrochemical companies is doing just that. Z Energy recognises the fossil fuel industry is an inherently unsustainable one, and continued investment in this area is detrimental to future generations. Instead, the energy company uses its profits to invest in biodiesel initiatives (The Spinoff, “The Petrol Company That Says It Wants To Save The World”). By providing an alternative to fossil fuels, Z Energy is attempting to counteract the negative results of its main business. While this course of action is not applicable to all corporations, there are paths forward for corporations to take moral responsibility for contributing to climate change and to mitigate their actions independently.

CliFin: Impact Investment

Climate change also provides financial opportunities for those willing to take the risk. Impact investment as CliFin offers a way. By seeking to maximise the social and environmental impact of their investments, individuals and investment groups influence social and technological developments. Investing in technologies and funds that work to mitigate the effects of climate change allows investors to take an active interest in developments that improve the environment. For example, in order to mitigate the effects of increased CO2 emissions, investing capital in initiatives decrease these emissions. There are two major vehicles for impact investment in the climate sector identified by the Global Impact Investment Network (GIIN): the Energy Access Debt Fund (EADF, managed by responsAbility Investments AG), and the Beyond the Grid Fund (BtGF, managed by SunFunder).

Both funds focus on the promotion of clean energy sources in less-developed parts of the world. The EADF focuses on Sub-Saharan Africa and the Asia-Pacific region, while BtGF focuses on Sub-Saharan Africa, India, and the Pacific. It has typically been the case that as a nation or region develops, it goes through a period of reliance on fossil fuels for energy. This industrialisation is then followed by a drive towards alternative energy sources. However, the promotion of clean energy sources will serve to bypass this reliance on fossil fuels. By doing so, CO2 emissions from energy generation is minimised. The BtGF has already shown some promising results. Due to the financing provided, 412,000 tonnes of CO2 emissions have been mitigated annually, while 4.5 million individuals now have access to fossil-free energy (Global Impact Investing Network, “Sunfunder Beyond The Grid Fund”). Impact investment may be one of the best financial options for investors to directly mitigate climate change through their own actions. It provides a way for financial capital to mitigate climate change, while obtaining tangible climate related benefits in the short term.

Works Cited

Bank of England, “Enhancing banks’ and insurers’ approaches to managing the financial risks from climate change”, Consultation Paper, October 2018.

Bennetts, Mike. “The Petrol Company That Says It Wants To Save The World.” The Spinoff, www.thespinoff.co.nz/partner/nzi-sbn-awards/22-11-2018/the-petrol-company-that-says-it-wants-to-save-the-world/

Carney, Mark. “A Transition in Thinking and Action”, International Climate Risk Conference for Supervisors, 6 April 2018, De Nederlandsche Bank, Amsterdam. Address.

Carbon Disclosure Project, Carbon Majors Report 2017. Accessible via www.cdp.net/en/articles/media/new-report-shows-just-100-companies-are-source-of-over-70-of-emissions

Davis, Nicola. “Iceberg twice size of Luxembourg breaks off Antarctic ice shelf.” The Guardian, www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jul/12/giant-antarctic-iceberg-breaks-free-of-larsen-c-ice-shelf

Financial Conduct Authority, “Climate Change and Green Finance”, Discussion Paper, October 2018.

Global Impact Investing Network, “Energy Access Debt Fund”, https://thegiin.org/case-study/energy-access-debt-fund

Global Impact Investing Network, “Sunfunder Beyond the Grid Fund”, https://thegiin.org/case-study/sunfunder-beyond-the-grid-fund

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, “Speical Report on Global Warming of 1.5ºC.” 2018, https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/

Le Quéré et al., “Global Carbon Budget 2018”, Earth System Science Data,vol. 10, no. 4, December 2018, 2141 – 2194.

Meyer, Robinson. “Since 2016, Half of All The Coral in the Great Barrier Reef has Died.” The Atlantic, www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2018/04/since-2016-half-the-coral-in-the-great-barrier-reef-has-perished/558302/

Pidcock, Roz. “The Most Influential Climate Change Papers of All Time.” CarbonBrief, www.carbonbrief.org/the-most-influential-climate-change-papers-of-all-time

Time Magazine Cover retrieved from http://content.time.com/time/covers/0,16641,20060403,00.html