Labor Exploitation: Case Study of Top Glove

By Londra Ademaj

This case study examines the allegations of forced labor in the manufacturing process of gloves by Top Glove, a prominent Malaysian rubber glove manufacturer. Malaysia, a diverse Southeast Asian country situated on the Malay Peninsula, serves as the home of this multinational corporation. Founded in 1991 by Tan Sri Dr. Lim Wee Chai in Malaysia, Top Glove Corporation Bhd has emerged as the global leader in rubber glove manufacturing, making a profound impact on the industry. Starting as a small local enterprise with just one factory and a single glove production line, Top Glove has experienced rapid expansion, solidifying its position as a global leader in the glove manufacturing industry (Top Glove). The case study explores the factors behind Top Glove’s success, examines the labor exploitation allegations that tarnished its reputation, considers the ethics regarding worker treatment, and details the responsibilities of corporations and governments.

Unravelling Top Glove’s Path to a Distinguished Status

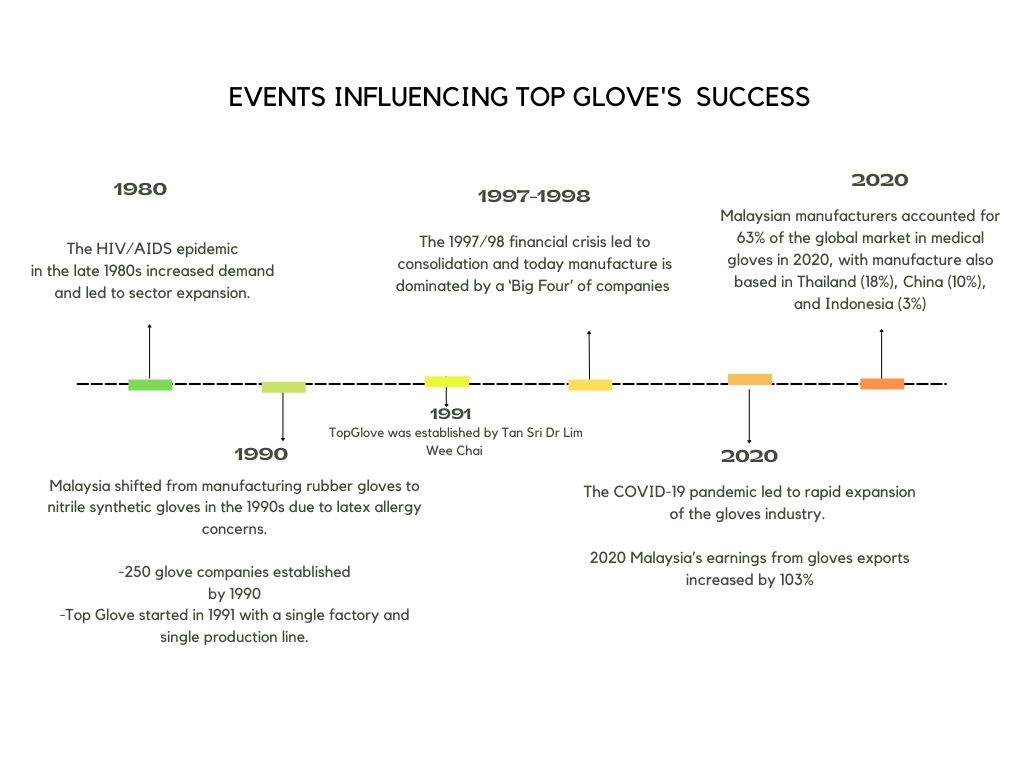

Figure 1 – Data sourced from (Hughes et al.)

The growth of multinational corporations like Top Glove in the rubber glove industry is heavily influenced by the contextual factors at play. The diagram presented below serves as a visual representation of the pivotal events that have played a significant role in contributing to its global success [Figure 1].

Remarkably, the expansion of Top Glove can be traced back to a series of unforeseen events, which carried both positive and negative consequences for the company. Although these events may not have been favorable for the overall economy, they played a pivotal role in propelling Top Glove’s ascent into the realm of a multinational corporation:

- In 1980, the demand for rubber gloves surged due to the HIV and AIDS epidemic. However, Top Glove was not established until 11 years later when regulatory changes mandated the transition from latex to synthetic nitrile gloves to address latex allergies. This move placed Top Glove in a highly competitive market, with approximately 250 other glove companies already operating by 1990 (Hughes et al.) Product differentiation was minimal, and competition was fierce.

- The Asian financial crisis of 1997-98 brought about an unexpected shift in the industry. Glove manufacturers collaborated, resulting in the formation of an oligopoly market where a few dominant players, known as the “big four,” controlled the industry (Hughes et al.). Since this development, the demand for gloves has remained stable over time due to their essential nature in hospitals and healthcare settings. This inelastic demand has provided a foundation for Top Glove’s continued expansion. This market structure presented an opportunity for Top Glove to consolidate its position and experience growth on an international scale.

- Since the Asian financial crisis, the COVID pandemic emerged as the next significant global event. The growth during the pandemic was significant, prompting Top Glove to expand its product line by manufacturing face masks. In 2020, Malaysian manufacturers, including Top Glove, captured a substantial 63% share of the global medical glove market, truly cementing their international presence. (Hughes et al.).

While the journey of Top Glove in the glove industry may seem remarkable, it is important to critically assess the factors that have contributed to its growth. Regulatory changes, financial crises, and the recent pandemic have all played a role in shaping Top Glove’s fortunes. The company has capitalized on market opportunities and adapted to changing circumstances. Yet, there exists broader implications, including the potential for labour exploitation to occur.

Labor exploitation can be challenging to define precisely. Marxists view exploitation as the unequal exchange of labor for goods (Roemer 30–65), while Adam Smith argues that it stems from the private property system, making worker justice unattainable under capitalism, particularly with profit-driven multinational corporations (Fairlamb 193–223). In the context of this case study, labor exploitation contains an element of criminal offences of forced labor or human trafficking which themselves constitute modern slavery.

Behind The Scenes: Top Glove

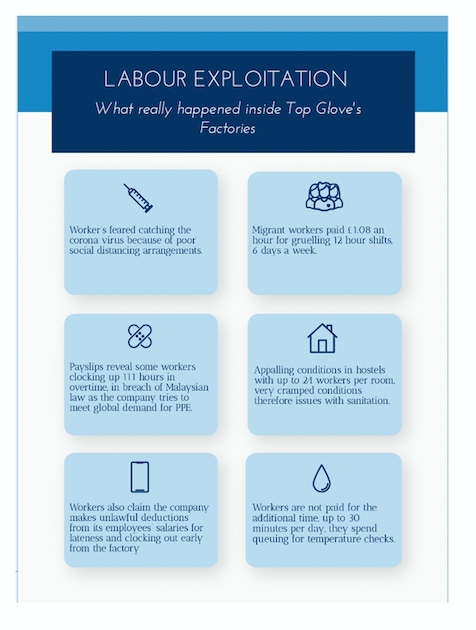

Top Glove has faced significant criticism and scrutiny regarding its labor practices. In 2020, the company came under the spotlight for alleged labor exploitation and poor working conditions (Business & Human Rights Resource Centre). Reports revealed mistreatment of migrant workers, excessive overtime, low wages, cramped living quarters, and other labor rights violations. These revelations raised concerns about the ethical practices and social responsibility of Top Glove, leading to international backlash and investigations by various organizations and authorities.

The allegations first emerged in 2018 through the diligent efforts of investigative journalists. The British Department of Health treated these accusations with utmost seriousness, recognizing the immediate need for further investigations (Marmo and Bandiera). As the investigations progressed, the shocking reality of illicit and inhumane practices resembling modern-day slavery became apparent. Top Glove, a prominent industry player, found itself implicated in a range of exploitative activities, including debt bondage, and forced labour (Marmo and Bandiera). For a more comprehensive understanding of the specific incidents that unfolded within the Top Glove factories, please refer to Figure 2.

Figure 2- Data Sourced from Marmo and Bandiera

Understanding the Roots of Labor Exploitation

Top Glove, Hartalega, and Kossan, the major Malaysian players in this industry, collectively employ nearly 34,000 workers (Zaugg). A significant proportion of these workers are recruited from abroad, primarily from countries like Indonesia, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Myanmar. This recruitment pattern is driven by the limited job opportunities available in their home countries, further intensifying their dependence on securing a job within these renowned Malaysian manufacturing companies.

The dependence on specific factories for employment creates an unjust power imbalance between employers and workers, leading to a range of adverse consequences. Employers are aware of the desperate need for jobs among workers, leaving the latter susceptible to exploitation. In their fear of unemployment and with limited options, workers may be compelled to accept unfavorable conditions such as low wages, long working hours, and inadequate safety measures. This power asymmetry perpetuates a cycle of disadvantage and erodes workers’ rights and well-being. Low wages not only impede their ability to meet basic needs but also hinder social mobility and trap them in a cycle of poverty. At the same time, workers are frequently subjected to long working hours without sufficient rest or breaks, leading to physical and mental exhaustion. This unfortunate outcome compromises their health and overall well-being.

Moreover, the absence of proper safety measures within these factories exposes workers to a multitude of significant risks and hazards inherent in the glove manufacturing process. Accidental exposure to toxins is a grave concern, as workers may come into contact with harmful chemicals and allergens during various stages of production (Boersma). Due to a lack of proper training and limited access to personal protective equipment (PPE), workers are exposed to the risk of developing occupational illnesses and enduring long-term health consequences. The improper handling of chemicals without adequate precautions can lead to immediate injuries, such as burns or skin irritations. The manufacturing industry for latex gloves is known to carry a high level of risk due to the presence of carcinogens, acids, strong alkalis, and dangerous drugs, posing significant health hazards (Yari et al.).

The lack of resources became apparent during the COVID-19 pandemic when groups of workers contracted the virus. Despite engaging in a global effort to supply protective equipment for the coronavirus, the company experienced a troubling situation. While enjoying record profits from shipping gloves worldwide, critics argue the company’s low-paid workers in Malaysia faced a severe outbreak of Covid-19 due to inadequate protections provided by the company(Beech).

Furthermore, the rubber glove industry operates under an oligopoly market structure, exacerbating the problem of exploitation. In the Malaysian market, Top Glove reigns as the dominant force, holding an impressive 26% share of the world market (Top Glove), ironically, keeping their position at the “top”. During the pandemic, the market control of Top Glove was further intensified as there was a significant increase in global demand. To meet production targets, labour had to operate beyond maximum capacity.

Making the situation worse, Top Glove introduced a scheme called “Heroes for COVID-19,” where workers were requested to voluntarily work up to 4 additional hours on their day off to package gloves. However, this scheme has been criticized for bypassing labor regulations and coercing workers into working 7 days a week (Marmo and Bandiera). The intention was to portray these workers as heroes for those hospitalized by COVID-19, but in reality, it was merely a ploy to lure in workers. The harsh reality is that over 5,000 Top Glove workers tested positive for COVID-19, and tragically, one worker lost their life, making Top Glove facilities responsible for Malaysia’s largest cluster of COVID-19 cases(Marmo and Bandiera).

Labor exploitation allegations predate the COVID-19 pandemic, indicating that it was not solely caused by the health crisis. However, the pandemic acted as a catalyst, making labor exploitation more noticeable and drawing attention to the issue. It is important to understand that labor exploitation may have been an ongoing problem before the pandemic, extending beyond its time frame. Top Glove’s dominant position in the industry often leads to cost-cutting measures, including the minimization of labor costs. Unfortunately, this strategy results in the exploitation of workers to maintain competitive pricing and maximize profits. Surprisingly, despite its monopoly power, Top Glove’s operating profit margin of 12.3% indicates inefficiencies in operating costs. These relatively small profit margins may directly contribute to labor exploitation, particularly when compared to competitors like Riverstone Holdings Limited, which enjoys a higher operating profit margin of 39.3% (Gek).

Exploring the Factors that Keep Workers in Harsh Conditions

Migrant workers are issued with a Visit Pass Temporary Employment (VP TE) for Malaysia. The VP TE enables a stay of 12 months after which it must be renewed if the worker remains in employment. Unfortunately, the Immigration Regulations prohibit a change of employer or employment, meaning a migrant worker’s VP TE is tied to a single employer and workers are unable to move elsewhere (Hughes et al). This means labor is de facto [la1] immobile, and individuals cannot work elsewhere unless in illicit forms of employment.

As the reliance on foreign labor has increased, there has been a corresponding rise in concerns regarding working and living conditions faced by workers. Consider the labor laws and regulations in Malaysia, Thailand, China, and Vietnam, where these manufacturing facilities are located. While these countries have labor laws in place to protect workers’ rights, the effectiveness of implementation and enforcement can vary. Large corporations, including glove manufacturers, may take advantage of loopholes and weaknesses in the system, exploiting leeway’s in laws and regulations. Additionally, inadequate labor inspection systems and limited regulatory oversight further compound the issue. Notably, Malaysian law allows for working hours that exceed the widely accepted maximum of 60 hours per week and permits work on designated rest days (Lee et al.). This highlights how labor exploitation is more likely to occur when labor laws are inadequate or lacking in their protective measures.

Global Impact of Labor Exploitation

As investigations delved deeper into working conditions within the factories, the impact of these extends far beyond national borders, making waves in the international trading market. In response to the distressing revelations, many countries took swift action by imposing bans on Malaysia’s exports of medical gloves, starting with the USA in 2020.

This sudden shift cast Malaysia as the focal point of forced labor issues, attracting attention and concern from around the globe. Rosey Hurst, and the founder of Impactt, a London-based ethical trade consultancy, succinctly expressed, “Malaysia has become the poster child” for these pressing labor concerns (Lee et al.).

The ban on US imports on July 2020 was triggered by a tragic incident at Top Glove, where an employee succumbed to Covid-19. The virus rapidly spread throughout the company’s factories and worker dormitories, leading Malaysian authorities to describe the conditions as overcrowded, uncomfortable, and lacking proper ventilation. Subsequent measures were implemented to contain the outbreak (Palma). As a result, the US Customs and Border Protection took decisive action by ordering the seizure of Top Glove’s products upon arrival at American ports, citing allegations of forced labor. The consequences of such a reputation are not confined to public perception but also manifest in tangible economic damage. This development had a significant impact on the reputation of one of the world’s largest corporate beneficiaries during the pandemic (Palma). It contributed to double-digit declines in revenue and net profit. Revenue and profit fell 22% and 29% respectively (Kumar). It is a stark reminder of how labor exploitation can have profound and far-reaching implications, impacting not just individuals but also international trade dynamics (Lee et al.)

Around the time the ban was introduced, Top Glove released a press statement firmly denying all allegations and emphasizing their unwavering dedication to labor governance. In their official communication, the company asserted (Alam):

- “Top Glove’s workers do not perform excessive overtime and are given rest day in line with the Malaysia labor law requirement, which is 104 hours of overtime per month and one (1) rest day per week, respectively. “

- “Maximum allowable overtime is 4 hours per working day and solely on a voluntary basis.”

- “To ensure compliance with Malaysian labor law requirements, Top Glove has implemented a digital monitoring exercise.”

Just a few months after the press release, there came a significant development as the United States decided to lift the import ban on Malaysia’s Top Glove. As a testament to their ongoing efforts, Top Glove published a comprehensive improvement report, detailing the actions taken since the allegations surfaced, despite consistently refuting any involvement in exploitative practices. In this report, they highlighted significant improvements in several areas, including (Top Glove):

1.Fair Recruitment Practices of Foreign Workers

2. Continuous Improvement of Workers’ Accommodation

3. Fair Working and Wages of Workers

4. Continued Safety and Health of Our Workforce

5. More Stringent Safety Measures to Safeguard Our Workforce Post COVID 19

Not only did Top Glove make information about its standards available, but other leading companies also contributed by sharing their assessments. Amfori, a prominent global business association focused on open and sustainable trade, recently conducted a social audit of Top Glove. In this assessment, Top Glove was proudly awarded an ‘A’ rating, signifying their dedication to upholding exemplary social standards. This recognition from Amfori highlights Top Glove’s commitment to transparency and responsible business practices (Jaafar).

Top Glove’s ‘A’ rating was the outcome of a comprehensive social audit conducted from June 23 to 26. The audit results reflected 12 areas assessed as “very good” and one area as “good,” showcasing some improvements. It is worth noting that Top Glove engaged with various organizations to enhance its social compliance and performance (Jaafar).

Because of these improvements, the bans on Top Glove’s products were lifted, causing an initial boost in the market. Top Glove shares rose by as much as 10% during early trading, although they later experienced a decline. With the ban lifted, Top Glove can now proceed with their previously disrupted plan of a $1 billion dual listing in Hong Kong, which was postponed due to the import ban (Ruehl and Langley).

Bengtsen argues that the import ban on Top Glove achieved what decades of voluntary corporate social responsibility (CSR) efforts by the global medical sector and actions by Malaysia’s labor inspectorate failed to accomplish. He suggests that the ban’s effectiveness was due to its direct impact on the company’s revenues, making it a crucial aspect to consider (Fanou).

These unfolding events give rise to critical questions regarding accountability and necessitate an examination of potential challenges within Malaysia. It raises the question of whether the responsibility should solely rest on Top Glove as a multinational corporation or if there is a larger systemic issue at play. The absence of appropriate legislation and the presence of exploitative practices indicate the need to scrutinize the wider labor landscape and regulatory framework within Malaysia (Palma).

The initial lack of response from Malaysia’s labor department regarding potential changes to the country’s labor laws, and the trade ministry’s silence on inquiries about potential investment losses, raises concerns about addressing labor rights issues (Lee et al.). However, as time progressed, the labor department in Malaysia has charged Top Glove with 10 counts of failing to provide worker accommodation that meets the minimum standards of the labor department in 2021. (Lee) Despite this, an independent consultant, Impactt, said it “no longer” found any indication of systemic forced labor at Top Glove, which was making progress on some indicators, such as living conditions (Lee).

These observations emphasize the need for greater attention and efforts from both multinational corporations and government bodies involved in the industry to address and mitigate labor exploitation.

It calls for a deeper understanding of the challenges that allow labor exploitation to persist and raises the urgency to address them to ensure the well-being and dignity of workers for a more equitable and just society.

Ethics Evaluation

The emergence and growth of Top Glove, coupled with the allegations of labor exploitation, raise intricate ethical considerations that demand in-depth examination. The treatment of workers within the company’s operations reveals a troubling disregard for their fundamental rights and well-being.

One of the fundamental ethical considerations centers around the principle of human dignity. Human dignity is crucial as it forms the foundation for justifying and upholding human rights.

At its core, the concept of human dignity asserts that every individual possesses inherent worth and value solely by virtue of being human. This belief is reflected in Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which proclaims that “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” (Soken-Huberty)

The idea of human rights is as simple as it is powerful: that people have a right to be treated with dignity. Human rights are inherent in all human beings, whatever their nationality, place of residence, sex, national or ethnic origin, color, religion, language, or any other status (Heard).

The alleged mistreatment of workers, including excessive working hours, low wages, and inadequate living conditions, violates their inherent dignity as individuals. Such practices strip workers of their basic rights, compromise their physical and mental well-being, and perpetuate a cycle of exploitation. Upholding the principle of human dignity is crucial in ensuring fair and equitable treatment of all individuals within the workforce.

Transparency and accountability are also critical ethical dimensions. Corporations like Top Glove have a moral obligation to operate transparently and be held accountable for their actions. The alleged labor exploitation within the company brings to light concerns regarding corporate responsibility, corporate governance, and supply chain management. Holding corporations accountable for their actions is crucial in fostering a culture of ethical behavior and ensuring labor rights are upheld.

Today, human rights have taken on a profound significance, akin to a form of religion. They serve as a powerful moral compass, guiding us in evaluating how a government treats its people (Heard). When it comes to addressing the ethical concerns surrounding labor exploitation, a multifaceted approach becomes crucial.

The approach entails a commitment from corporations to prioritize the well-being and rights of workers, regulatory bodies to enforce and strengthen labor standards, and society at large to raise awareness and demand ethical practices. By fostering a culture of ethics and social responsibility within the industry, it becomes possible to create a labor environment that upholds the dignity and rights of all workers.

The United Nations’ “Protect, Respect, and Remedy” framework serves as a global standard for preventing and addressing the potential negative impact on human rights associated with business activities (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights). This framework consists of three pillars:

- The duty of the state to protect human rights.

- The responsibility of corporations to respect human rights.

- The necessity for enhanced access to remedies for victims of human rights abuses linked to business practices.

While international human rights treaties generally do not impose direct legal obligations on businesses, the International Bill of Human Rights, and the core conventions of the International Labour Organization (ILO) provide fundamental guidelines for businesses to comprehend the essence of human rights, how their own operations may influence them, and how to ensure proactive measures are in place to prevent or mitigate potential adverse impacts (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights).

While recognizing challenges in ensuring strong protections for human rights and labor rights in Malaysia, significant efforts have been made to improve the situation.

For instance, the Bureau of International Labour Affairs collaborated with the Malaysian government on projects aimed at enhancing labor rights and enforcement. These initiatives have included assisting the national government in drafting laws, decrees, and regulations to strengthen labor protections. Efforts have also been focused on providing information and guidance to employers regarding these regulations, promoting compliance and awareness (Bureau of International Labour Affairs).

Additionally, there have been endeavors to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of labor administration in Malaysia. This involves initiatives such as strengthening labor inspections to ensure that legal instruments are enforced. The labor ministry or relevant authorities play a key role in overseeing and conducting these inspections (Bureau of International Labour Affairs).

Mechanisms for resolving labor disputes have been established to provide workers in Malaysia with accessible avenues to seek justice and find resolution in case of rights violations. These measures aim to ensure that workers’ rights are upheld and protected in the country (Bureau of International Labour Affairs).

Labor rights involve not just corporations and the state, but civil society as well, playing a vital role. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) focusing on social and economic rights are particularly instrumental in providing direct services to individuals who have suffered human rights violations.

These services offered by NGOs can take various forms, such as providing humanitarian assistance to those in need, offering protection for vulnerable individuals, or facilitating training programs to empower individuals with new skills. In cases where labour rights are legally protected, NGOs may engage in legal advocacy, offering advice and guidance on how to present claims or seek legal recourse. (Council of Europe)

The involvement of civil society organizations adds an essential dimension to the overall effort in promoting and safeguarding labor rights. Their direct services and support help bridge the gap between human rights violations and the necessary assistance needed by those affected. Through their dedicated work, NGOs contribute to creating a more just and inclusive society where individuals can assert their labor rights and access the support they require. (Council of Europe)

In Malaysia, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have played a significant role in combating labor exploitation across various industries. Notably, Transparentem has emerged as a prominent NGO dedicated to bringing about transformation in the industry by shedding light on uncomfortable realities.

Transparentem’s primary objective is to uncover and disclose hidden truths, ultimately driving positive change within industries. By exposing the harsh realities and working conditions, the organization aims to raise awareness and prompt necessary action to address labor exploitation.

Transparentem’s leaders have learned from past experiences that when investigators reveal appalling conditions in Asia, embarrassed Western customers tend to hastily terminate their relationships with suppliers but make little effort to rectify the abuses (Greenhouse). To avoid this pattern, Transparentem takes a different approach. When they uncover serious problems, instead of rushing to publicize them and expose the factories’ Western customers, the organization discreetly informs these companies and urges them to collaborate with the factories to address the issues. The underlying understanding is that Transparentem will eventually disclose its investigative findings and how companies have responded. Western companies are aware that their reputation will be tarnished if they fail to take appropriate action (Greenhouse).

In conclusion, the case study of Top Glove, a Malaysian rubber glove manufacturer, highlights both the remarkable success achieved by the company and the concerning allegations of labor exploitation that have marred its reputation. The growth of Top Glove within the global industry can be attributed to various factors such as regulatory changes, financial crises, and the COVID-19 pandemic. The revelations of labor exploitation shed light on the ethical considerations and responsibilities that corporations and governments must address. Upholding human dignity, ensuring transparency and accountability, and fostering a culture of ethics and social responsibility help create a good labor environment.

Works Cited

Alam, Shah. “Press Release.” Www.topglove.com, 2020, www.topglove.com/single-press-release-en?id=98&title=top-glove-remains-firm-on-its-labour-governance.

Beech, Hannah. “A Company Made P.P.E. For the World. Now Its Workers Have the Virus.” The New York Times, 20 Dec. 2020, www.nytimes.com/2020/12/20/world/asia/top-glove-ppe-covid-malaysia-workers.html.

Boersma, Martijn. “Do No Harm? Procurement of Medical Goods by Australian Companies and Government.” Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation & the Australia Institute, Apr. 2017, https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.11024.61443.

Bureau of International Labor Affairs. “Support for Labor Law and Industrial Relations Reform in Malaysia.” DOL, www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/support-labor-law-and-industrial-relations-reform-malaysia.

Business & Human Rights Resource Centre. “Malaysia: Top Glove Denies Migrant Workers Producing PPE Are Exposed to Abusive Labour Practices & COVID-19 Risk; Incl. Responses from Auditing Firms.” Business & Human Rights Resource Centre, 2020, www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/malaysia-top-glove-denies-migrant-workers producing-ppe-are-exposed-to-abusive-labour-practices-covid-19-risk-incl-responses-from-auditing-firms/.

Council of Europe. “Human Rights Activism and the Role of NGOs.” Council of Europe, 2012, www.coe.int/en/web/compass/human-rights-activism-and-the-role-of-ngos.

Fairlamb, Horace L. Adam Smith’s Other Hand: A Capitalist Theory of Exploitation. 2nd ed., vol. 22, Florida State University Department of Philosophy, 1996, pp. 193–223, www.jstor.com/stable/23560336.

Fanou, Temisan. Literature Review: Forced Labour Import Bans. 2023, gflc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Forced-Labour-Import-Bans.pdf. Accessed 12 July 2023.

Gek, Tay Peck. “Among Glove Makers, Riverstone Has Most Attractive Margins.” The Business Times, 2022, www.businesstimes.com.sg/companies-markets/among-glove-makers-riverstone-has-most-attractive-margins.

Greenhouse, Steven. “NGO’s Softly-Softly Tactics Tackle Labor Abuses at Malaysia Factories.” The Guardian, 22 June 2019, www.theguardian.com/business/2019/jun/22/ngos-softly-softly-tactics-tackle-labor-abuses-at-malaysia-factories.

Heard, Andrew. “Introduction to Human Rights Theories.” Www.sfu.ca, 2019, www.sfu.ca/~aheard/intro.html.

Hughes, Alex, et al. “Global Value Chains for Medical Gloves during the COVID‐19 Pandemic: Confronting Forced Labour through Public Procurement and Crisis.” Global Networks, vol. 23, no. 1, Jan. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12360.

Jaafar, Syahirah S. “Top Glove Accorded ‘A’ Rating in Recent Social Audit by Amfori.” The Edge Malaysia, theedgemalaysia.com/article/top-glove%C2%A0accorded%C2%A0-rating-%C2%A0recent-social-audit-amfori.

Kumar, P. Prem. “Malaysia’s Top Glove Q3 Earnings Dented by US Import Ban.” Nikkei Asia, June 2021, asia.nikkei.com/Business/Companies/Malaysia-s-Top-Glove-Q3-earnings-dented-by-US-import-ban.

Lee, Liz, et al. “Analysis: Malaysia’s Labour Abuse Allegations a Risk to Export Growth Model.” Reuters, 22 Dec. 2021, www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/malaysias-labour-abuse-allegations-risk-export-growth-model-2021-12-21/.

Lee, Liz “Malaysia Charges Top Glove over Poor Quality of Worker Housing.” Www.zawya.com, 2021, www.zawya.com/en/legal/malaysia-charges-top-glove-over-poor-quality-of-worker-housing-q1xsk52r. Accessed 8 July 2023.

Marmo, Marinella, and Rhiannon Bandiera. “Modern Slavery as the New Moral Asset for the Production and Reproduction of State-Corporate Harm.” Journal of White Collar and Corporate Crime, vol. 3, no. 2, June 2021, p. 2631309X2110209.

Miller, Jonathan. “Revealed: Shocking Conditions in PPE Factories Supplying UK.” Channel 4 News, 16 June 2020, www.channel4.com/news/revealed-shocking-conditions-in-ppe-factories-supplying-uk.

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. “The Corporate Responsibility to Respect Human Rights- an Interpretive Guide.” OHCHR, 2012, www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/publications/hr.puB.12.2_en.pdf.

Roemer, John. Should Marxists Be Interested in Exploitation? Wiley, 1985, pp. 30–65, www.jstor.org/stable/2265236.

Ruehl, Mercedes, and William Langley. “US Lifts Import Ban on Malaysia’s Top Glove over Alleged Forced Labour.” Financial Times, 10 Sept. 2021, www.ft.com/content/6e46bde0-355e-46fb-920b-f059fc5b84b5.

Soken-Huberty, Emmaline. “What Is Human Dignity? Common Definitions.” Human Rights Careers, 7 Apr. 2020, www.humanrightscareers.com/issues/definitions-what-is-human-dignity/.

Top Glove. “Continuous Improvement Report .” Www.topglove.com, www.topglove.com/continuous-improvement-report.

Palma, Stefania. “US Import Ban Bursts Top Glove Bubble.” Financial Times, 17 June 2021, www.ft.com/content/1f0634c0-8916-442b-a06a-ecde5507d2ea.

Top Glove. “The World’s Largest Manufacturer of Glove.” Www.topglove.com, 2023, www.topglove.com/corporate-profile#:~:text=Top%20Glove%20Corporation%20Bhd%20was.

Yari, Saeed, et al. “Assessment of Semi-Quantitative Health Risks of Exposure to Harmful Chemical Agents in the Context of Carcinogenesis in the Latex Glove Manufacturing Industry.” Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, vol. 17, no. sup3, June 2016, pp. 205–11, https://doi.org/10.7314/apjcp.2016.17.s3.205.

Zaugg, Julie. “The World’s Top Suppliers of Disposable Gloves Are Thriving because of the Pandemic. Their Workers Aren’t.” CNN, 2020, edition.cnn.com/2020/09/11/business/malaysia-top-glove-forced-labor-dst-intl-hnk/index.html.

Image courtesy of Top Glov