Greenwashing: The Dow Jones Sustainability Indices Case

By Yashi Wang

In fall of 2018, the non-governmental organization Friends of the Earth publicized accusations at Dow Jones Sustainability Indices for ‘greenwashing’ (Thompson). In particular, it criticized the inclusion of palm oil company Golden Agri-Resources in the Asia Pacific index. While there are valid concerns about how Golden Agri-Resources came to be included despite evidence against ethical and sustainable conduct, the accusations of ‘greenwashing’ by the index provider are not entirely appropriate. If anything, it may be more productive to focus on the flaws in the system of evaluation.

Case of Golden Agri-Resources: Key Players

Dow Jones Sustainability Indices (DJSI)

The Dow Jones Sustainability Indices span a collection of well-regarded indices that rank the sustainability performance of thousands of publicly traded companies across the globe. They are curated through S&P Dow Jones Indices’ partnership with RobecoSAM, and they are used as reference by both investors and companies. The family influences the investment of trillions of dollars in assets (Thompson). Indices include DJSI World, Europe, Nordic, North America and Asia Pacific, industry-specific indices, etc. Broadly, companies are evaluated and filtered based on economic, social, and environmental performance, as well as long-term plans in these areas. The selection criteria evolve each year for new review, and a number of companies enter and exit the index each year.

RobecoSAM (Sustainable Asset Management)

RobecoSAM is a well-known Swiss-based investment group that assesses sustainability performance of companies across the globe and provides sustainability benchmarking reports to companies. RobecoSAM uses a rules-based selection process based on companies’ Total Sustainability Score, which is taken from its annual Corporate Sustainability Assessment (CSA). The DJSI selection process begins with approximately 10,000 companies from the S&P Global BMI. Around 4,500 companies are invited for participation but only a portion of these companies participate and receive an analysis. The final global indices include the top 10% most sustainable bodies, based on scores, while regional indices like the Asia-Pacific index include the top 20% (“DJSI Index Family”). Outside of its partnership with DJSI, RobecoSAM also participates in the S&P Fossil Fuel Free index family, ESG factor Indices, and the S&P ESG index family.

Friends of the Earth (FoE)

Friends of the Earth is an environmental nongovernmental organization (NGO). It campaigns on issues like deforestation, pollution, sustainable agriculture, and finance and economic systems’ role in a more environmentally sustainable world (tax policies, strengthening regulations, lending practices, etc.). It was the main complainant about Golden Agri-Resources’ inclusion in the DJSI for a second year in 2018, labeling the decision ‘greenwashing’.

Golden Agri-Resources (GAR)

Golden Agri-Resources (E5H:SES) is a Singapore-based palm oil company. It became the first and only palm oil company to be listed by the DJSI in September 2017. Palm oil production is crucial for manufacturing products from ice cream to cosmetics, but the scope of the industry, environmental impact, and the particularly high land usage have been problematic for the industry’s sustainability reputation. Misconduct involving deforestation and indigenous displacement seems to be recurrent (Thompson).

Golden Veroleum Liberia (GVL)

Golden Veroleum Liberia is a palm oil company in West Africa financed by Golden Agri-Resources. GVL is a subsidiary of Verdant Fund LP, a private equity fund, in which GAR is the sole investor. The close relationship means GVL’s questionable behavior also reflects upon GAR.

The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO)

This industry body is a non-profit organization set up in 2004 through negotiations between the World Wildlife Fund and companies. It gathers representatives across the palm oil supply chain and sectors — producers, processors, traders, manufacturers, retailers, banks/investors, and NGOs — in a body intended to design and implement an international standard of sustainability for palm oil. Compliant companies produce Certified Sustainable Palm Oil (“About Us”).

The organization itself has been criticized for poor oversight and greenwashing. In 2015, Grassroots and the Environment Investigation Agency (EIA) jointly produced a report identifying a myriad of problems with RSPO’s systems. These included fraudulent coverups by auditors, conflicts of interest between companies and the certification body, weak understanding of the sustainability standard within the certification body, and failure to identify labor abuses, indigenous land claims, labor trafficking, and so on (EIA and Grassroots).

Events and Allegations

The 2015 EIA report on RSPO used Golden Agri-Resources as one of its case studies, citing a body of evidence on GAR’s noncompliance that were not addressed by RSPO. In 2013, NGOs Forest Peoples Programme and TUK-Indonesia had interviewed communities in Indonesia, learning that GAR had obtained land without their voluntary consent (EIA and Grassroots 9). Yet in the fall of 2017, GAR became the first and only palm oil company listed by DJSI. Even amidst above allegations of “land grabbing, environmental destruction, and violations of international sustainability principles” filed with RSPO (Madan).

In February 2018, The RSPO acted on complaints and censured GVL for mishandling of community relations. The certification body noted the coercion and intimidation of villagers into signing agreements, destruction of local communities’ sacred sites, and continued development on lands where its ownership is disputed (Madan). GVL appealed the decision, lost the appeal, and subsequently withdrew from the RSPO body, resulting in general concern about its commitment to best practice. “This is a blatant attempt by GVL and GAR to evade their obligations to the RSPO,” said James Otto of Monrovian NGO Sustainable Development Institute. “They use their RSPO membership to attract investment and to market their palm oil but when their bluff is called they just walk away from their responsibilities.”

Because GAR is the ‘financial backbone’ of GVL, NGO representatives believe that GAR needs to be equally responsible and accountable for the environmental, human rights, and worker rights violations in the Liberian operations (Dixon). GAR spokeswoman Wulan Suling claimed that GAR lacked ‘management control’ over GVL, though it’s the majority investor. Tom Lomax, legal and human rights program coordinator at Forest Peoples Programme believes that, even without a direct management role, GAR has significant decisive influence at GVL due to its financial stake (Pye).

Thus, the FoE demands that the DJSI stop greenwashing GAR and instead recognize its many faults, or else risk betraying its mission of sustainable investing (Madan). DJSI responded that RobecoSAM, exists as an independent score provider used by DJI to determine eligibility – that it simply receives and makes decisions based on these reported scores. RobecoSAM responded that greenwashing doesn’t accurately describe the inclusion of GAR since its methodology is uniformly “robust and rules-based” in a way that GAR genuinely qualified for inclusion. GAR also defended itself against FoE, saying that it had fully cooperated and disclosed the required information during RobecoSAM’s evaluation process. GAR notes that the issues with GVL were available to RobecoSAM, and its score had been adjusted accordingly (Madan).

Through 2018, further complaints were brought against GAR itself by various NGOs, regarding land-grabbing, refusals to renegotiate unfair deals, and potential hidden ownership of shadow subsidiaries (which increase GAR’s landholdings above the land ceiling and allow destructive behavior outside of RSPO attention) (Otto and Colchester). They called for its suspension from RSPO and RSPO certifications.

Ultimately, GAR was removed from the DJSI Asia Pacific index in February 2019 following arrests of three executives for bribery and coverups of pollution and other misbehavior in Indonesia (“Palm Oil Giant”). As of February 2019, Forest Peoples Programme is criticizing RSPO for being less responsive to these accumulated events than DJSI (Dixon).

Analysis

Greenwashing

The term ‘greenwashing’ is a play on ‘whitewashing’. Conventionally, it refers to the usage of public relations and marketing to give a false impression of a company or company products’ environmental soundness, in order to capitalize on the demand for products fitting these standards. More specifically, it’s typically a diversionary tactic used to redirect consumers’ attention, away from problematic company behaviors and towards pleasant initiatives that are also far less consequential (Watson).

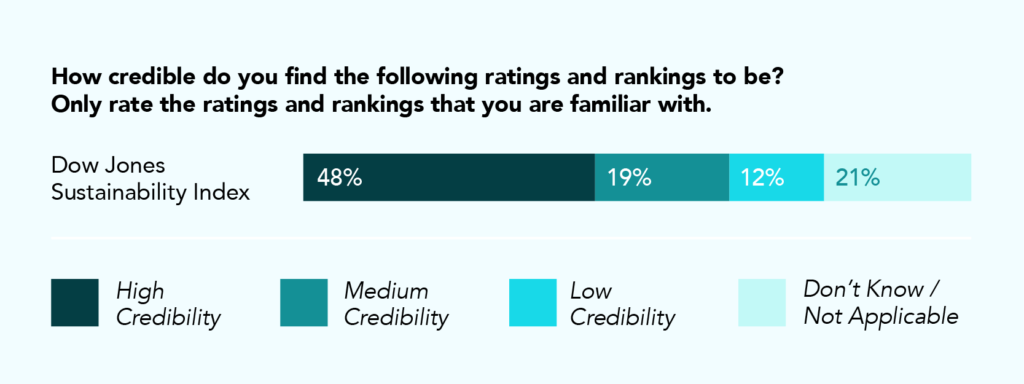

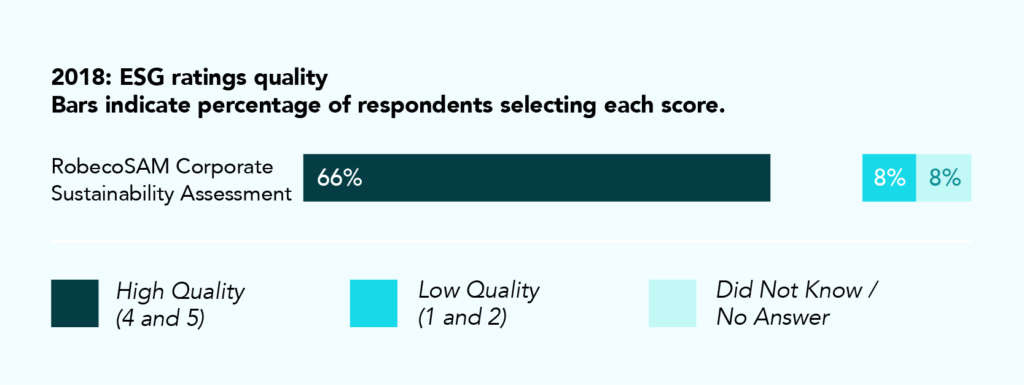

First, it’s doubtful that the inclusion of a company in a sustainability index can serve as a diversion from unsustainable behavior, when it is meant to be an evaluation of those behaviors. FoE’s attention itself already illustrates the implausibility of DJSI inclusion as a greenwashing tactic, since it only draws attention to company qualifications. Criticisms of selected companies are not new. They’ve popped up for cases like oilfield service giant Halliburton, oil company Enbridge, and other entities with well-publicized incidents that may feel like disqualifications (Siegel; Welsch). The think tank SustainAbility conducts ongoing research into ESG raters through surveying sustainability professionals across sectors. In 2012, their survey reflected that only 48% of respondents found the DJSI highly credible; this was already the highest level of confidence compared to other leading indices included by the survey (Sadowski 15). In their 2019 report, 66% of respondents rated the RobecoSAM assessment as high-quality/credibility (Wong et al. 16). While perceptions have improved over time, they reflect corporate professionals’ continual and natural response of a private evaluation when examining these compiled ratings and indices.

Secondly, to apply the concept to the current case poses a problem: the publicity and financial payoff from representation on a sustainability index flows towards the listed company. It’s true that the false impression of environmental soundness benefits the company, and it is conceivable that the company would take steps to greenwash itself. On the other hand, the accusations that DJSI, an independent entity, is greenwashing a listed company doesn’t seem to fit in the conventional definition. The narrative is further complicated by the usage of RobecoSAM, who is involved as a third-party evaluator. There is no evident conflict of interest.

Do these parties believe something went wrong? None of the three parties’ comments on FoE’s accusations addressed any sort of foul play. They have all insisted that the selection process functioned normally. Given this, the situation that avoids implying some sort of improbable coalition is a scenario where the company deliberately concealed or fabricated information, or was able to otherwise affect the ratings process to its own benefit. However, FoE accusations seem to say that DJSI and RobecoSAM missed out on public and obvious information. The alternative possibility is that the selection process itself was insufficient, that it did not take the GVL criticisms seriously enough.

Criticisms of Sustainability Assessment

It seems important to first categorize the criticisms and flaws of the sustainability rating process (and thereby the DJSI’s list inclusion process) by structural problems and behavioral problems. Structural problems reflect a byproduct of the existing system, while behavioral problems reflect an active and intentional choice. After all, greenwashing seems to imply a degree of intention, which is hard to claim here.

Structural Flaws

There is a sense in which the DJSI is especially passive. Instead of actively screening for appropriate companies, the DJSI takes advantage of the DJI as its parent index. The DJI is a broad “underlying universe” from which the sustainability index emerges through what is emphasized as a ‘rules-based’ process — that is, a reasonably efficient process to evaluate hundreds to thousands of companies (Windolph 68).

Efficiency produces some side effects. For example, tradeoffs exist due to single-value scoring — percentages, in the case of RobecoSAM. Single-value scoring is a concise method of rating that translates easily into index qualification through a superior score; it also means some stronger performances can compensate for weaknesses in other areas. The emphasis of some better-performing areas over others is, in a sense, a diversionary practice. In other words, behavioral. But the SAM weighting system is applied to swathes of companies, and a change that impacts the rating of one entity may not clarify others. This is a structural issue.

For example, RobecoSAM customizes weights on its criteria for each industry, such as ‘Construction & Engineering’ or ‘Electrical Components and Equipment’, under each industry group (in this case, ‘Capital Goods’). Criteria fall under three dimensions: the economic, the environmental, and the social. For Construction and Engineering, the total weights in 2019 for the dimensions are 35%, 31%, and 34%, respectively. For its next-door neighbor Electrical Components and Equipment, the weights are 43%, 29%, and 28%. Should the Construction & Engineering weights be adjusted, for example to match its neighbor, its companies’ performances in economic areas like risk and crisis management would be magnified, whether superior or poor, while their performances in social areas like human rights would move out of focus. This might drive one company off the index but boost another.

Behavioral Flaws

In the screening process, a lack of credible information also becomes a problem. Public data are limited, so that raters rely on companies to take part in surveys, or in the case of DJSI, a highly detailed questionnaire. However, this method is limited in its efficacy. Concealment of information certainly absolves the index and rater of greenwashing accusations. In the case of GAR, even if there was deliberate concealment of information (and based on the later discoveries that would delist GAR, there were), FoE’s criticisms targeted information that was already revealed courtesy of NGO investigations.

Bias can exist towards economic, social, or environmental dimensions. Windolph’s report suggests that SAM and DJSI are subject to an economic bias that emphasizes shareholder value. Economists criticize maximizing shareholder value (MVP) for its negative consequences (Lazonick). While this element may be a behavioral flaw, it seems to have improved since 2011.

Validity of Accusations Against DJSI

In 2018, FoE pushed a report describing how DJSI violates its own listing criteria. For example, RobecoSAM’s human rights criteria are violated by the coercive tactics and damage to local community sites that GVL and GAR have been accused of. Environmental degradation, including overconsumption of resources, water pollution, and other effects on community water services, offend criteria in the environmental dimension of the analysis. It’s possible that the economic dimension criteria are also violated through GVL’s tax optimization strategy.

Under these circumstances, the FoE report expresses disbelief that GAR was able to qualify for the index under the Food, Beverage and Tobacco sector, “the toughest sustainability index to qualify for”. While detailed knowledge of the scoring process for GAR is not available, an examination of the 2019 RobecoSAM scoring weights reveal some interesting information. The weights differ somewhat between sectors, so a comparison can be made between ‘Food, Beverage and Tobacco’ against ‘Materials (FRP Paper & Forest Products)’, which seems relevant to palm oil production in terms of similar issues like deforestation and supply chain management.

Tax strategy, an economic criterion, is weighted at 3% for forest products and only 2% for food. Human rights, a social criterion, is weighted 5% for forest products but only 3% for food. Water-related risks are weighted at 5% for forest products, and only 3% for food. The social impact on communities is weighted at 5% for forest products, but doesn’t appear in food criteria; neither does sustainable forestry practices, weighted at 6% for forest products but nonexistent for food. There is, however, a 3% regarding genetically modified organisms, an area in which GAR performed well in around 2017 and 2018 when it released new non-GMO and high-productivity seeds (“Golden Agri-Resources’ Latest Sustainability Report”).

This evidence show obvious inconsistencies that are problematic in terms of DJSI’s commitment to its own mission and its responsibility towards the investors using its service. However, the lack of motivation, intention, and even effectiveness (of ‘greenwashing’ as a diversional tactic) in this case seems to imply that greenwashing might not be the right way to characterize the issue. The label also doesn’t seem useful in a constructive context beyond pulling GAR off the list, when the same ‘rules-based’ ratings processes were applied across the board and would continue to be applied in the future. This is not a deliberate greenwash, but a structural inadequacy. In the end, inadequate assessment and methodology is not an unusual culprit, but at least an advantageous one, if exploited to help debug the system using the perceived flaws.

For example, Friends of the Earth spokesperson Gaurav Madan believed that none of the GVL content should have been unknown to DJSI, even if still unsubstantiated by RSPO. DJSI should have taken it into account regardless as part of the ‘Media and Stakeholder Analysis’ portion of the evaluation, making it more unbelievable to him that DJSI chose to include GAR. In this step, RobecoSAM monitors the media coverage and public research on companies to assess environmental, economic, and social risks (Mandan). CAS checks are made in areas like tax strategy, environmental policy, and human rights. GAR had also confirmed that RobecoSAM was aware of and took into account the negative media linked to GVL.

Much of the negative content that stands out to the accusatory NGOs existed as complaints lodged by NGOs to RSPO, but were not acted upon, and could really only be reflected in the Media and Stakeholder Analysis section as of 2017, when GAR was first selected.

In June 2018, RobecoSAM announced updated Media and Stakeholder Analysis procedures, causing serious fluctuations in company scoring. Rather than rewarding an absence of controversy, it will increase the negative score impact in proportion to severity of controversies (Vinke). RobecoSAM’s 2018 methodology review stated that it increased the Media and Stakeholder weight in response to increasing investor interest in corporate controversies. It observed that absolute scores did drop on average, though the leading companies didn’t budge much. While GAR initially made the list for a second year, it was later removed through the year-long monitoring process. This is a clear example of RobecoSAM’s dynamic and adaptive methodology that, if encouraged, would allow self-regulation.

Thus, it would be best to convert the greenwashing accusations against DJSI towards critical examinations of how the evaluation structure can better reflect sustainable and ethical intentions.

RSPO Failings

If anything, by the definitions examined, the RSPO may be the organization that engaged in noticeable greenwashing. By directing public attentions towards the palm oil industry’s awareness and apparent progress towards sustainability through its very existence, it provides a diversion from continual and even fashionably new forms of ethical violations and environmental destruction. By claiming the burden of responsibility, but not accountability, in rewarding and punishing industry entities, the RSPO does further injustice when it fails to respond to evidence of misconduct.

Prior to the RSPO’s sluggish suspension of IOI Group, a Malaysian conglomerate with a presence in palm oil, notable companies like Hershey’s and Dunkin’ sourced significant amounts of palm oil from them (Finkelstein and Glenn). While IOI’s deforestation violations were already publicized, companies used IOI’s RSPO affiliation to justify their continual transactions (Hurowitz).

The RSPO’s Board of Governors reserves four of sixteen seats for palm oil growers, and two each for processors/traders, manufacturers, retailers, banks/investors, environmental NGOs, and social NGOs (“About Us”). It’s superficially equal, but industry-dominated. As a certification body in the name of sustainability, it would not be absurd to propose a division that shifts authority towards non-corporate entities.

Even if responsibility were to be pushed further down, problems like conflicts of interest or ‘weak understanding of the sustainability standard’ within the certification body are reasonably correctable. There’s also reason to believe that its ‘certification principles’ are insufficient. A statement released by World Forest Movement and Friends of the Earth International in 2018 denounces a failure to address the industry’s reliance on qualified land. I.e. the RSPO implicitly allows the industry to continue to develop itself in the same growth trajectory that has always relied on a culture of violations.

For it to become a meaningful entity, one that companies like GVL cannot simply walk away from, the RSPO needs to reevaluate what its intentions are, what a ‘diverse’ representative body should really mean under the banner of sustainability, and how it can ensure the functional execution of its processes.

Bibliography

2018 RobecoSAM Corporate Sustainability Assessment – Annual Scoring & Methodology Review. RobecoSAM AG, 2018, 2018 RobecoSAM Corporate Sustainability Assessment – Annual Scoring & Methodology Review.

“About Us.” RSPO, www.rspo.org/about.

Dixon, Tom. “PRESS RELEASE: Palm Oil Giant Golden Agri-Resources Removed from Dow Jones Sustainability Index after Bribery and Corruption Scandal – so What next for ‘Sustainable’ Palm Oil?” Forest Peoples Programme, FPP, 6 Feb. 2019, www.forestpeoples.org/en/global-finance-trade-agribusiness-palm-oil-rspo/press-release/2019/press-release-palm-oil-giant.

“DJSI Index Family.” Robeco.com, RobecoSAM, www.robecosam.com/csa/indices/djsi-index-family.html.

EIA, and Grassroots. Who Watches the Watchmen?: Auditors and the Breakdown of Oversight in the RSPO. Environmental Investigation Agency UK Ltd., 2015, Who Watches the Watchmen?: Auditors and the Breakdown of Oversight in the RSPO.

Finkelstein, Joel and Glenn Hurowitz. “Deforestation Doughnuts.” Forest Heroes. June 6, 2014.

Friends of the Earth United States. Unsustainable Investment: GAR’s Continued Violations of Industry Standards and Sustainability Criteria, Preliminary Findings for the DJSI Index Committee. Friends of the Earth, Mar. 2018.

Golden Agri-Resources. “Are Ethical Indices Really Greenwashing the Palm Oil Sector?” Medium, Medium, 17 Oct. 2018, medium.com/@goldenagriresourcesltd/are-ethical-indices-really-greenwashing-the-palm-oil-sector-1a9594341785.

“Golden Agri-Resources’ Latest Sustainability Report Tracks Progress on Supply Chain Transformation.” Cision: PR Newswire, PR Newswire Association LLC., 29 June 2018, www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/golden-agri-resources-latest-sustainability-report-tracks-progress-on-supply-chain-transformation-300674586.html.

Hurowitz, Glenn. “RSPO: Completely Worthless, or Just Mostly Worthless? (UPDATED).” HuffPost, HuffPost, 31 Mar. 2017, www.huffpost.com/entry/rspo-completely-worthless_b_9579420.

Lazonick, William. “Profits Without Prosperity.” Harvard Business Review. 2014. Print.

Madan, Gaurav. “Is S&P Dow Jones Greenwashing Conflict Palm Oil? (Commentary).” Mongabay: News & Inspiration from Nature’s Frontline, Mongabay Environmental News, 16 Oct. 2018, news.mongabay.com/2018/10/is-sp-dow-jones-greenwashing-conflict-palm-oil-commentary/.

Otto, James, and Marcus Colchester. “5 New Complaints Filed against Indonesia’s Largest Palm Oil Company.” Forest Peoples Programme, Forest Peoples Programme, 16 Aug. 2018, www.forestpeoples.org/en/node/50274.

“Palm Oil Giant Golden Agri-Resources Removed from Dow Jones Sustainability Index after Bribery and Corruption Scandal.” Friends of the Earth, Friends of the Earth International, 5 Feb. 2019, foe.org/news/palm-oil-giant-golden-agri-resources-removed-dow-jones-sustainability-index-bribery-corruption-scandal/.

Pye, Daniel. “Palm Oil Giant’s Claim It Can’t Control Liberian Subsidiary a ‘Red Herring,’ NGO Says.” Mongabay: News & Inspiration from Nature’s Frontline, Mongabay Environmental News, 12 Sept. 2018, news.mongabay.com/2018/09/palm-oil-giants-claim-it-cant-control-liberian-subsidiary-a-red-herring-ngo-says/.

Sadowski, Michael. Rate the Raters: Phase Two, Taking Inventory of the Ratings Universe. SustainAbility, 2010, Rate the Raters: Phase Two, Taking Inventory of the Ratings Universe.

Siegel, RP. “When Pigs Fly: Halliburton Makes the Dow Jones Sustainability Index.” Environmental News Network, ENN, 24 Sept. 2010, www.enn.com/articles/41814-when-pigs-fly–halliburton-makes-the-dow-jones-sustainability-index. Accessed 21 July 2019.

Thompson, Jennifer. “Friends of the Earth Accuses Ethical Index Provider of ‘Greenwashing’.” Financial Times, Financial Times, 14 Oct. 2018, www.ft.com/content/e53bef54-fef0-3dcf-8cdc-39bc9ebf40ac?desktop=true&segmentId=d8d3e364-5197-20eb-17cf-2437841d178a.

Vinke, Nikkie. “New DJSI MSA Methodology Shakes Up 2018 Results.” Finch & Beak Consulting, Finch & Beak, 8 June 2018, www.finchandbeak.com/1373/new-djsi-msa-methodology-shakes-2018.htm.

Watson, Bruce. “The Troubling Evolution of Corporate Greenwashing.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 20 Aug. 2016, www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2016/aug/20/greenwashing-environmentalism-lies-companies.

Welsch, Edward, and Ben Lefebvre. “Wisconsin Spill Complicates Enbridge Plans.” The Wall Street Journal, Dow Jones & Company, 30 July 2012, www.wsj.com/articles/SB10000872396390444226904577559482764343646.

Windolph, Sarah Elena. “Assessing Corporate Sustainability Through Ratings: Challenges and Their Causes.” Journal of Environmental Sustainability, vol. 1, no. 1, 2011, pp. 1–22., doi:10.14448/jes.01.0005.

Wong, Christina, et al. “Rate the Raters 2019: Expert Views on ESG Ratings.” SustainAbility, SustainAbility, 25 Feb. 2019, sustainability.com/our-work/reports/rate-raters-2019/.

World Rainforest Movement, and Friends of the Earth International. “RSPO: 14 Years of Failure to Eliminate Violence and Destruction from the Industrial Palm Oil Sector.” Friends of the Earth International, 13 Nov. 2018, www.foei.org/news/rspo-violence-destruction.