Ethics Review: Global Minimum Corporate Tax

By Carmen Pegas

130 countries and jurisdictions of the OECD Inclusive Framework, representing more than 90% of global GDP, have recently reached a historic agreement to reform international taxation rules (1). The new rules set a global minimum corporate tax of at least 15% on liable multinational corporations (MNEs) and introduce new legislation for corporations to be taxed where they operate and earn profits, even if they have no physical presence in those areas. These rules would deter MNEs from avoiding taxation by shifting profits to low-tax jurisdictions, putting an end to tax havens (2). A detailed implementation plan will be finalized in October, and the new taxation rules could be effectively implemented as soon as 2023 (2).

The current system for taxing multinational corporations is inadequate and allows for tax avoidance (3). It has also encouraged the detrimental race to the bottom on corporate taxation, which fueled inequality and lowered needed public revenue globally (4). The agreement on a global minimum corporate tax is a critical step in the right direction regarding just taxation, and will most likely have a net benefit in the global economy (5). However, the current proposal raises issues of international equity (6). It is vital that the tax works for the benefit of all economies and takes into special consideration the needs of developing countries, to not exacerbate existing inequalities (7).

The Need for an International Tax Reform

The international corporate tax system currently rests on a century-old architecture that has proved incapable of keeping up with the twenty-first century global economy (8). Reform is urgently needed to address three main problems with our current system.

Profit-Shifting and Tax Avoidance

Our outdated international tax system permits base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS). MNEs can exploit loopholes in taxation rules by, for instance, setting up a local branch in a tax haven and declaring profits there, because corporations are only legally liable to pay the local rate, even if those profits mainly come from elsewhere (9) (10). MNEs are estimated to shift $1.38 trillion worth of profit a year, equivalent to 40% of all profits (11), costing governments $245 billion in lost tax revenue every single year (3). Developing countries suffer disproportionately with this loss of revenue due to their higher reliance on corporate income taxes. Further, advanced economies have historically shaped international corporate tax rules without considering their impact on the developing world, so the complexity of the current system works to developing countries’ detriment. An IMF analysis concluded non-OECD countries suffer a $200 billion loss of revenue per year, critically impeding their ability to grow and reduce extreme poverty (12).

MNEs are estimated to shift $1.38 trillion worth of profit a year, equivalent to 40% of all profits, costing governments $245 billion in lost tax revenue every single year.

The digitization of the global economy increased tax avoidance opportunities. In the last few decades, the emergence of profitable, technology-driven business models reliant on intangible assets – such as patents, software and copyright (13) – eradicated the need for physical proximity to target markets (14). Currently, nexus rules – rules that give jurisdictions the right to tax – determining where taxes should be paid, are based on physical presence of MNEs in a country or jurisdiction (14). A country with millions of users of a social media app, for example, might receive no tax from this company because it has no physical presence in that country. Nexus rules that rely on physical presence as a legal basis for tax liability have, then, allowed profitable firms to exploit a country’s markets without being liable for taxes (9). Governments urgently need a new allocation of profit rights from income generated through cross-border activities.

Race to the Bottom in Corporate Taxation

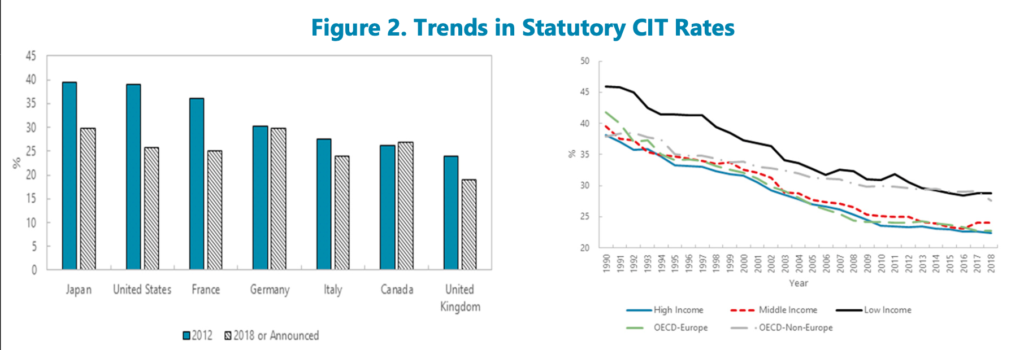

Harmful tax competition is eroding government revenue globally. For the past four decades, countries have slashed their corporate tax rates to attract MNEs and remain competitive. Chart 1 shows this problematic trend in statutory rates of corporate income taxes (12). The losses from this race to the bottom are possibly much higher than those from avoidance: OECD estimates the overall revenue loss from avoidance is around 10% of corporate income tax revenue, which would equate to a 2.5% cut in the corporate income tax rate. In the last 50 years, the global average tax rate fell by more than 15% (15).

A race to the bottom is prejudicial for all. As noted by Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz, “There is no evidence that lower taxation globally leads to more investment. If a country lowers its tax relative to others, it might ‘steal’ some investment, but this beggar-thy-neighbor approach doesn’t work globally.” (16).

Oxfam identifies the race to the bottom in corporate taxation as one of the driving forces of the inequality crisis (4). Taxation is a powerful tool to redistribute wealth and allows governments to invest in education, healthcare, and address poverty. There is ongoing debate about who bears the burden of corporate taxes, but many organizations, including the Tax Policy Centre, US Congressional Budget Office and US Joint Committee on Taxation, estimate 80% of the tax burden falls on capital and shareholders, while 20% falls on labour (17). Share ownership is strongly related to household income (18), so taxing corporate profits would be a very progressive form of taxation. The fall in corporate tax rates therefore hinders redistribution and exacerbates inequality (4).

Issues of Fairness and Political Pressure

There is political pressure to reform the international tax system because it goes against the public’s idea of fairness. French Finance minister said about the corporate tax proposal, “We owe it to our citizens and companies, especially SMEs (small and medium-sized enterprises), who pay their fair share of taxes” (19). Especially in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic that left SMEs and workers struggling financially, big multinational corporations having a lower effective tax rate than small local businesses is an unpopular policy, because it feels unfair.

Fairness has been defined as a normative principle to suggest ethical outcomes that ought to occur (20) and the concept encompasses giving to each what they deserve (21). Although definitions and applications of the term vary, agents’ moral intuitions are equipped to recognize unfairness.

In the realm of taxation, both progressive and flat rate taxation can be arguably considered fair. Flat rate taxation, that assigns the same rate to all taxpayers (22), can be justified with regards to nondiscrimination fairness: everyone, rich or poor, must contribute the same and no one is unequally burdened (of course, much can be said about the how the rich and the poor are very differently affected by having to part with the same percentage of their income). Progressive taxation, on the other hand, is based on principles of distributional fairness (23). While a flat rate ignores the differences between the rich and the poor, progressive taxation aims to lessen the tax burden on the poor, because they have less disposable income and spend a higher percentage of it on their basic needs. However, no concept of fairness justifies paying proportionately less when you have more. People recognize MNEs with much higher profits have the advantage of benefitting from international tax avoidance strategies, sometimes ending up paying less effective tax than small and medium local-only companies. Recent data show Amazon pays 11.8% in effective tax, Facebook 12.2% and Apple 14.4%. Reasonable people would label these low taxes as unfair (24).

Overview of the Proposed Global Minimum Corporate Tax Plan

The proposed tax reform rests on two pillars, that together aim to address tax challenges arising from the digitalization of the economy. Pillar 1 establishes new nexus rules and Pillar 2 imposes a floor on tax competition, which are both needed to address BEPS.

- Pillar One

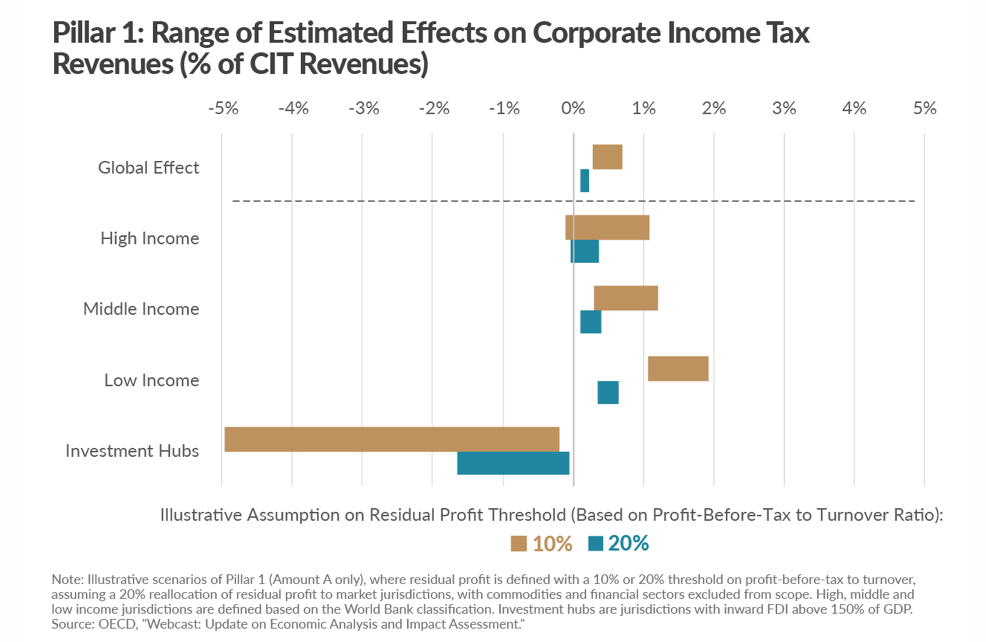

The first Pillar changes nexus rules – that determine where tax will be paid – and profit-allocation rules – that determine what portion of MNEs profits will be taxable (25). Simply put, it would reallocate some taxing rights over MNEs from where they are headquartered to the jurisdictions where they operate and earn profits – i.e. market jurisdictions – regardless of whether the corporations have a physical presence in those jurisdictions (2). It is expected to reallocate more than $100 billion of profit annually to market jurisdictions (2). Estimated effects on corporate income tax revenues are graphed in Chart 2.

Pillar One has three components: Amount A, Amount B and Tax Certainty.

Amount A allocates 20%-30% of residual profit – profit that exceeds 10% of revenue – of an MNE to market jurisdictions (25). Companies in Pillar One’s scope are MNEs with global turnover over 20 billion euros and profitability above 10%. The new nexus rules for amount A will be based solely on an MNE’s sales in a market jurisdiction. For most jurisdictions to have a right to tax an MNE, the MNE will have to derive at least EUR 1 million in revenue from it.

Let’s consider a very simple example to understand how Amount A would work in practice. Imagine an in-scope MNE that makes all its revenue from selling an app to users. All its sales are made in country 1 and 2, where it has no physical presence. The MNE derives more than EUR 1 million from sales in each country. With the current taxation system, countries 1 and 2 have no right to tax the MNE, even though it attains revenue from their populations. Amount A would allow both countries to tax a portion of the MNE’s residual profits based on the sales within each country.

Whereas amount A provides market jurisdiction with a new taxing right, amount B simplifies the administration of current tax rules. It establishes a standard remuneration for marketing and distribution arrangements – “activities involving purchasing from related parties and reselling to unrelated parties, and routine distributor functionality” – physically taking place in a market jurisdiction (26). The transactions in the scope of amount B could be, for example, an enterprise purchasing products from a foreign enterprise belonging to the same MNE group to sell to customers in its home country.

Let’s consider another simple example of this kind of transaction. An MNE group, Z, has enterprises in both country 1 and country 2, Z1 and Z2 respectively. Z1 buys hardware from Z2 to sell to its customers in country 1. Amount B would establish a standard remuneration for this transaction. The difficulty in taxing these kinds of distribution arrangements means they are often the subject of dispute between tax authorities (25). Standardization of amount B aims to simplify these processes to avoid controversy between tax administrations and taxpayers. It is hoped that it will enhance tax certainty, reduce compliance and administration costs for MNEs, and provide additional revenues for jurisdictions with low tax administrative capacity, especially in developing countries (27).

Lastly, Pillar One focuses on enhancing tax certainty across all possible areas of dispute between tax authorities. The proposals in this pillar intersect with the current profit allocation system, so there must be reconciliation between the new taxing right and the existing system to avoid double taxation. Therefore, Pillar One proposes dispute prevention and resolution mechanisms around amount A and B (25).

The threshold for a MNE to be liable for amount A will likely prove insufficient. With the current proposed threshold, Pillar One would only apply to 100 of the most profitable corporations (28), although its scope might widen a few years after its implementation. A member of MNE Tax spoke out on this issue, questioning the fairness of the threshold and highlighting that taxation problems are common with taxpayers other than with the biggest MNEs, as major multinationals often adopt conservative policies to avoid reputation issues (29). Further, major MNEs, such as Amazon, whose turnover and market capitalization have significantly increased but whose profit margin does not exceed the 10% threshold might not even be liable to the new rules. This outcome does not fulfil the reform’s goal of addressing the tax challenges arising from a digitalized economy (30). Extractives and regulated financial services are also excluded from the deal, which sparked discontent (25).

- Pillar Two

Pillar Two introduces a global minimum corporate tax to attenuate competition over corporate income tax and protect countries’ tax bases (31). In essence, it would allow a “right to ‘tax back’ where other jurisdictions have not exercised their primary taxing rights, or the payment is otherwise subject to low levels of effective taxation”. Therefore, all MNEs would pay a minimum level of tax, regardless of where they are located (31). Pillar Two with a minimum rate of at least 15% is expected to generate $150 billion in tax revenue annually (31). Pillar Two comprises two interlocking “GloBE” – “Global Anti-Base Erosion” – rules, and a treaty-based rule.

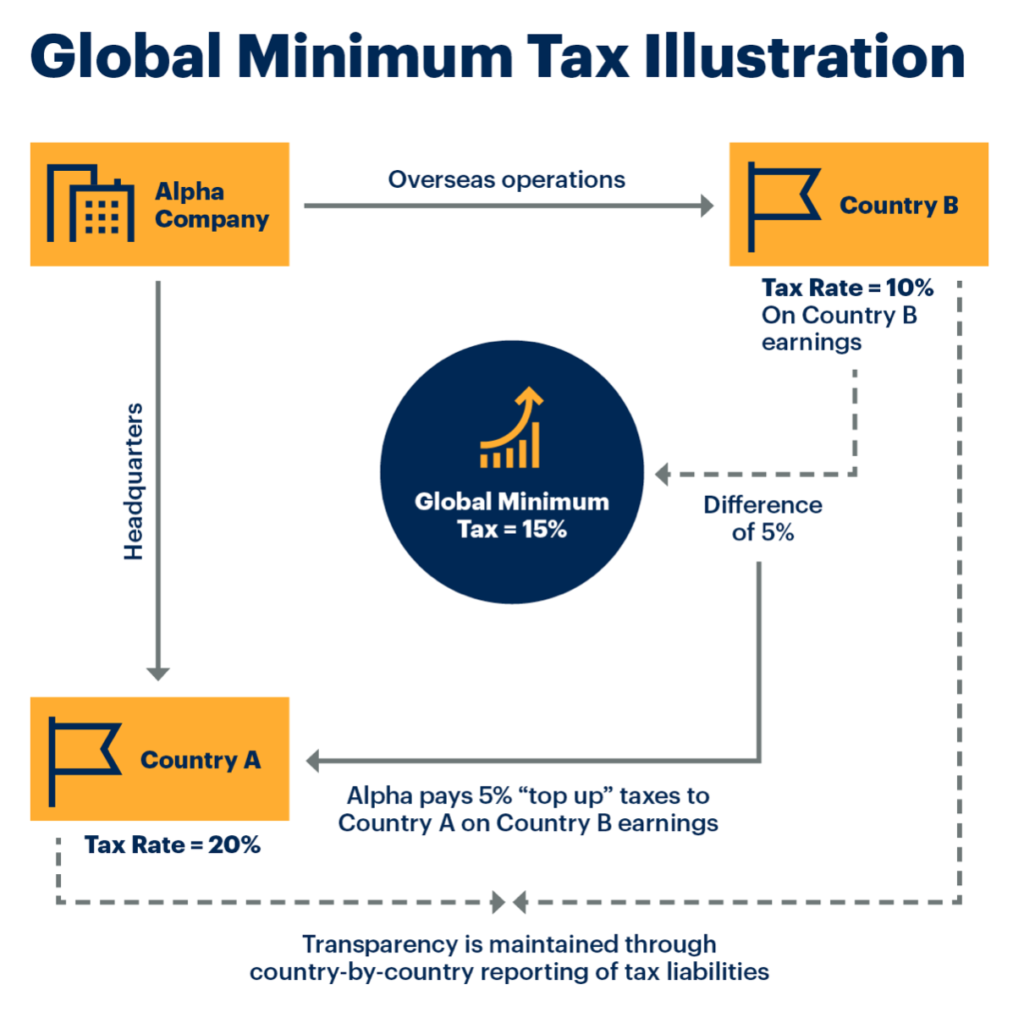

The principal GloBE rule is the Income Inclusion Rule (IIR). It creates an additional “top-up tax” to be paid in the parent entity’s jurisdiction when the profits of any of the group companies located in another country are taxed at an effective tax rate below the minimum tax rate. This minimum rate is yet to be definitively decided, but the OECD claims it should be at least 15%. Consider the example mapped in Chart 3 (31).

The Under-Taxed Payment Rule (UTPR) is a secondary rule applied when the IRR is unable to, by itself, bring low-tax countries to comply with the minimum rate (32). It denies deductions or requires an equivalent adjustment when the low tax income of a constituent entity is not subject to tax under IIR (31). This rule could apply when the parent entity of an MNE group is resident in a low tax jurisdiction, for example (33). In this case, the mechanism of the IIR explained above would be ineffective. Any top-up tax would, then, be collected by countries in which other group companies are located, until it meets the minimum threshold.

MNEs with consolidated group revenue of 750 million euros in the preceding fiscal year will fall within the scope of the GloBE rules.

Finally, the Subject to Tax Rule (STTR) complements the GloBE rules, targeting intra-group payments considered to be high-risk from a BEPS perspective (34). The tax for STTR would be set between 7.5% and 9% (33).

The proposed 15 percent minimum rate has been criticized by those advocating for more just corporate taxation. It falls well below the UN Financial Accountability, Transparency and Integrity recommendation, that called for 20 to 30% global corporate tax on profits (35). There are also fears that the rate is too low to prevent harmful tax competition and that it will spark a new “race to the minimum” (35). On the other hand, low-tax jurisdictions, such as Ireland (12.5% rate) and Paraguay (10% rate), find the proposed level too high because it would take away their competitive edge for foreign direct investment (FDI) (36).

Pros and Cons of the Tax: Utility Calculations

Utilitarianism – the view that the morally right action is the one that produces the most good or utility (37) – provides us with a helpful tool to determine whether the proposed plan should be implemented. We can predict its consequences and determine if its net impact on the global population will most likely be positive or negative.

Advantages of the Tax Reform

Firstly, the tax reform would yield around 150 billion in additional global tax revenue yearly. This is a non-negligible amount, especially now that governments need to raise revenue to handle the high level of public debt resulting from necessary but costly expenditure during the pandemic (38). The pandemic and subsequent crisis affected the poorest the most (39) and exacerbated already rising economic inequality. Crucially, therefore, low- and middle-class citizens should not bear the burden of fiscal consolidation measures like tax increases and cuts in social welfare programs. As discussed, only 20% of the Global Minimum Corporate Tax is expected to fall on labor (17), so it could serve as a crucial stream of revenue that does not strain average citizens, and may even relieve them of tax burden in times of crises (40). Total public social expenditure is negatively related to poverty and inequality (41), so increased government revenue from the tax reform might ameliorate these issues.

Secondly, the tax could stop the race to the bottom on corporate taxation occurring since the 1980’s (42). Putting an end to this harmful tax competition hinders the rise in inequality and helps restore depleted public finances (4). If the current trend in worldwide average statuary corporate tax rates prevails, it would also preserve countries’ tax bases and prevent even larger government revenue losses in the future when rates inevitably get closer to zero. Protecting tax bases in developing countries is especially important, because when not offering tax incentives, governments are able to retain more revenue for their development and rely less on borrowing and aid.

Disadvantages of the Tax Reform

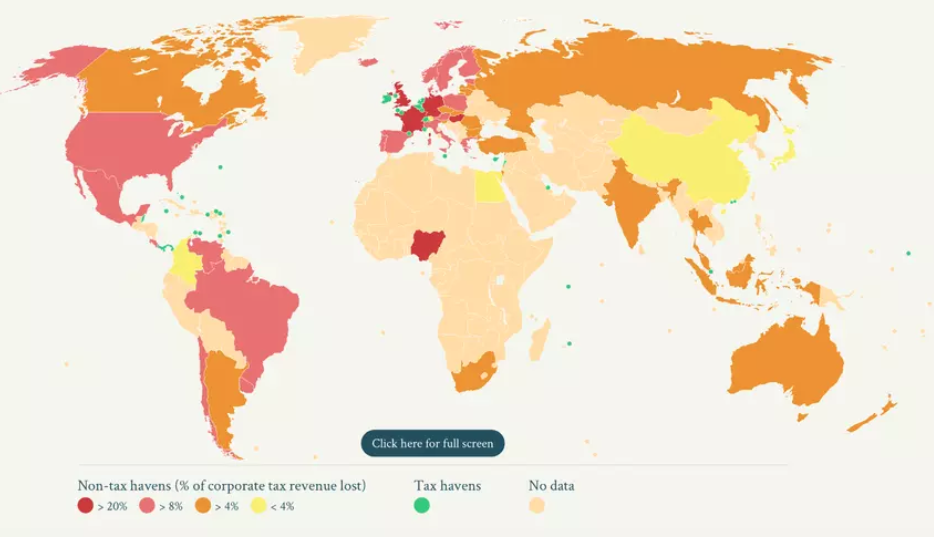

Firstly, the tax will lead to massive localized losses in zero-tax jurisdictions, such as Bermuda and the British Virgin Islands, as well as more modest but significant losses in low-tax countries, like Bulgaria and Macedonia, because of their reliance on low taxes and incentives to attract FDI (See Chart 4 for location of tax havens) (43). The British Virgin Islands, for example, although making nothing in corporate-tax revenue, heavily relies on fees from subsidiaries of large companies and from corporate-service providers that appeared in the region to serve them. Corporate and financial services accounted for over 60% of government revenue in 2018 (44). Although corporate tax havens apply lower effective tax rates, they manage to attract such large quantities of artificial profits that they are the biggest tax collectors in the world (45). This explains why many countries engage in a detrimental race to the bottom in corporate taxation, as well as how much they stand to lose with the implementation of the tax reform.

Secondly, the tax reform would increase the tax burden on business investment, which could decelerate global economic growth. The Tax Foundation notes businesses that use low-tax jurisdictions to facilitate cross-border investments would see an increase in taxes on their current projects and face a new tax deterrent on future projects, resulting in lower FDI (46). Studies looking at the cross-border investment flow do suggest FDI decreases on average 3.7%, following a 1% increase in the tax rate (47). Business investment decisions can result in reductions of operations and employment, with spillover effects for communities where they are located. However, it should be noted the empirical literature on the impact of corporate taxes on economic growth reaches ambiguous conclusions (48).

Net Effect of the Tax Reform

Utilitarian calculations seem to favor the proposed tax reform. The proposal has the potential to redistribute a substantial amount of wealth globally. The revenue collected could be utilized in welfare programs that benefit the public, potentially having a net positive effect on the life of billions. This possible consequence justifies Biden’s designation of the tax as “a foreign policy for the middle class” (49); it aims to ensure globalization and trade are harnessed for the benefit of all citizens, not just MNEs and millionaires. The localized losses the proposed tax brings to tax havens and the possible loss of FDI (and its ambiguous consequences on economic growth) are simply not enough to outweigh its possible net benefits.

International Equity and Developing Nations

OECD Secretary-General Mathias Cormann said that the tax reform “accommodates the various interests across the negotiating table, including those of small economies and developing jurisdictions” (2). However, many argue developing countries’ needs are taking a backseat in the negotiations and that the proposal is “skewed to the rich” (50).

Impact of the Proposal on the Developed World

There are concerns developing nations are being excluded from the negotiations. The Chief Executive of the Tax Justice Network said that the extremely modest benefits developing countries might collect from the reform shows that the G7 and the OECD are unfit to lead the accord, and that the negotiations should be moved to the UN to get a deal that works for all, not just the developed world (51).

As it stands, the G7 and the EU would receive more than two-thirds of the new revenue a minimum global corporate tax of 15% would yield, while the world’s poorest countries would see a mere 3% (50). Why this huge disparity? According to Pillar 2, countries where multinational companies are headquartered are given first priority to tax undertaxed profits, under the IIR rule. These countries are usually richer, capital exporting economies (52). So, even if profits and, in many cases, labor and raw materials are sourced from developing countries, the bulk of the tax revenue would go to rich countries where MNEs are headquartered (53). The distribution of benefits from taxation, then, threatens to increase already high levels of inequality between developing and developed countries, by retaining wealth in the global North (54). Clearly, the negotiations should acknowledge these issues and cater for differences in economic development.

Potential Solutions

Prominent organizations and leaders in developing countries have proposed changes to make the tax reform more equitable and in-line with the interests of the developing world.

Firstly, the narrow scope of Pillar One, that would cover only 100 of the world’s largest MNEs, leads to a low level of profit reallocation, in particular to smaller markets jurisdictions (53). The African Tax Administration Forum is calling for a tiered approach where nexus thresholds would be set lower for smaller economies (55), as a threshold for most would not be equitable due to differences in magnitude. In addition, they advise a reallocation of at least 30% of residual profit, instead of the proposed 20%-30%.

Secondly, many have warned the 15% minimum rate is not high enough because the rules for Pillar Two’s implementation will not result in much revenue for developing countries (56). The Independent Commission for the Reform of International Corporate Taxation warned that a low minimum rate could spark a race to the minimum (57). There is some evidence that a race to the bottom forces developing countries to follow suit, even though they can’t afford comparatively lower tax rates (58). So, a potential race to the minimum would be extremely disadvantageous for developing countries, many of whom have corporate tax rates well above 15%. The rate should, then, be set higher than 15%, at least at 20%, argues the Commission (54).

Thirdly, to avoid tax revenues being topped up in countries where multinational companies maintain their headquarters, developing countries could institute a domestic minimum tax to match the global rate (56).

Lastly, as explained above, due to the primary rule being IIR, developing countries might not gain much additional tax from Pillar Two because it benefits residence jurisdictions, usually rich and developed countries. Mathew Gbonjubola, head of Nigeria’s delegation of the Inclusive Framework said this outcome was “opposed to the initial understanding and expectation that the countries where those revenues arose should have first choice” to tax them. Prioritizing the UTPR rule, a source-based rule, would address the current imbalance in the allocation of taxing rights between residence – where MNEs are headquartered – and source jurisdictions – where they operate and earn revenue (59).

References:

- Thomas, Leigh. “130 Countries Back Global Minimum Corporate Tax of 15%.” Reuters, 2 July 2021, www.reuters.com/business/countries-backs-global-minimum-corporate-tax-least-15-2021-07-01.

- “130 Countries and Jurisdictions Join Bold New Framework for International Tax Reform – OECD.” OECD, 1 July 2021, www.oecd.org/newsroom/130-countries-and-jurisdictions-join-bold-new-framework-for-international-tax-reform.htm.

- Tax Justice Network. “What Is Profit Shifting?” Tax Justice Network, 25 Feb. 2021, taxjustice.net/faq/what-is-profit-shifting.

- Berkhout, Esmé. “Tax Battles” Oxfam Policy Paper, 2016.

- Goldstein, Jeff. “The Case for a Global Minimum Corporate Tax.” Atlantic Council, 7 Apr. 2021, www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/the-case-for-a-global-minimum-corporate-tax.

- Wheatley, Jonathan. “Biden’s Global Tax Plan Could Leave Developing Nations ‘next to Nothing.’” Financial Times, 10 May 2021, www.ft.com/content/9f8304c5-5aad-4064-9218-54070981fb4d.

- Keeley, Brian. “What’s happening to income inequality?”, in Income Inequality: The Gap between Rich and Poor, OECD Publishing, 2015.

- Lagarde, Christine. “Corporate Taxation in the Global Economy.” IMF Blog, 25 Mar. 2019, blogs.imf.org/2019/03/25/corporate-taxation-in-the-global-economy.

- Micossi, Stefano and Paola Parascandolo, “The taxation of Multinational Enterprises in the European Union – Views on the options for an overhaul”. CEPS Policy Brief, vol. 203, 2010.

- “Base Erosion and Profit Shifting.” OECD, 2021, www.oecd.org/tax/beps.

- Zucman, Gabriel, “Taxing Multinational Corporations in the 21st Century”. EFIP Policy Brief, vol. 10, 2019.

- International Monetary Fund, Fiscal Affairs Dept. “Corporate Taxation in the Global Economy”. IMF Policy Papers, no. 19/007, 2019.

- Kenton, Will. “Understanding Intangible Assets.” Investopedia, 29 May 2020, www.investopedia.com/terms/i/intangibleasset.asp.

- “Action 1.” OECD, 2021, www.oecd.org/tax/beps/beps-actions/action1.

- OECD, “Addressing the Tax Challenges of the Digital Economy, Action 1 – 2015 Final Report”, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, OECD Publishing, 2015.

- Stiglitz, Joseph. “The Race to the Bottom on Corporate Taxation Starves Us of the Resources We Need to Solve Our Biggest Problems.” MarketWatch, 8 Oct. 2019, www.marketwatch.com/story/the-race-to-the-bottom-on-corporate-taxation-starves-us-of-the-resources-we-need-to-solve-our-biggest-problems-2019-10-07.

- Nunns, James R. “How TPC Distributes the Corporate Income Tax.” Tax Policy Center, 13 Sept. 2012, www.taxpolicycenter.org/publications/how-tpc-distributes-corporate-income-tax/full.

- Saad, By Lydia. “What Percentage of Americans Owns Stock?” Gallup.Com, 23 Mar. 2021, news.gallup.com/poll/266807/percentage-americans-owns-stock.aspx.

- Kinder, Tabby, and Emma Agyemang. “‘It’s a Matter of Fairness’: Squeezing More Tax from Multinationals.” Financial Times, 8 July 2020, www.ft.com/content/40cffe27-4126-43f7-9c0e-a7a24b44b9bc.

- Suranovic, Steven, “International Trade Fairness” CHALLENGE, 1997.

- Velasquez, Manuel, et al. “Justice and Fairness.” Markkula Center for Applied Ethics, 1 Aug. 2014, www.scu.edu/ethics/ethics-resources/ethical-decision-making/justice-and-fairness.

- Uradu, Lea D. “Is a Progressive Tax More Fair Than a Flat Tax?” Investopedia, 31 Jan. 2021, www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/042815/progressive-tax-more-fair-flat-tax.asp.

- Dator, Jim et al.“What Is Fairness?” Fairness, Globalization, and Public Institutions: East Asia and Beyond, University of Hawai’i Press, 2006, pp. 19–34.

- “Biden’s Plans for a Global Corporate Tax Rate Could Make the World a Fairer Place.” The Guardian, 11 Apr. 2021, www.theguardian.com/politics/2021/apr/11/bidens-plans-for-a-global-corporate-tax-rate-could-make-the-world-a-fairer-place.

- OECD, “Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Report on Pillar One Blueprint: Inclusive Framework on BEPS”, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, OECD Publishing, 2020.

- “The ABCs of BEPS Pillar One Explained.” Vistra, 29 Apr. 2020, www.vistra.com/insights/abcs-beps-pillar-one-explained.

- Higinbotham, Harlow. “Amount B: Facts and Circumstances Matter—Even for Routine Distributors.” Bloomberg Tax, 5 Feb. 2021, news.bloombergtax.com/daily-tax-report/amount-b-facts-and-circumstances-matter-even-for-routine-distributors.

- Thériault, Annie. “OECD Inclusive Framework Agrees Two-Pronged Tax Reform and 15 Percent Global Minimum Tax: Oxfam Reaction.” Oxfam International, 9 July 2021, www.oxfam.org/en/press-releases/oecd-inclusive-framework-agrees-two-pronged-tax-reform-and-15-percent-global-minimum.

- Prescott-Haar, Leslie. “The Pillar One Blueprint — the Potential Future of International Taxation and Transfer Pricing –.” MNE Tax, 14 Oct. 2020, mnetax.com/the-pillar-one-blueprint-the-potential-future-of-international-taxation-and-transfer-pricing-40662.

- Jolly, Jasper. “Global G7 Deal May Let Amazon off Hook on Tax, Say Experts.” The Guardian, 7 June 2021, www.theguardian.com/technology/2021/jun/06/global-g7-deal-may-let-amazon-off-hook-on-tax-say-experts.

- OECD, “Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Report on Pillar Two Blueprint: Inclusive Framework on BEPS”, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, OECD Publishing, 2020.

- “International Tax: Pillar Two – The New Normal for Effective Tax Rates.” Baker McKenzie InsightPlus, 14 Oct. 2020, insightplus.bakermckenzie.com/bm/tax/international-oecd-pillar-two-blueprint-released-full-summary-attorney-advertising#cntAnchor4.

- Bunn, Daniel. “What’s in the New Global Tax Agreement?” Tax Foundation, 19 July 2021, taxfoundation.org/global-tax-agreement.

- Ernst & Young’s International Tax Services. “U.S. International Tax This Week for July 2.” Ernest & Young Tax Rules, 2 July 2021, taxnews.ey.com/news/2021-1292-us-international-tax-this-week-for-july-2.

- Oxfam International. “OECD Inclusive Framework Agrees Two-Pronged Tax Reform and 15 Percent Global Minimum Tax: Oxfam Reaction.” Oxfam International – Press Releases, 9 July 2021, www.oxfam.org/en/press-releases/oecd-inclusive-framework-agrees-two-pronged-tax-reform-and-15-percent-global-minimum.

- Goodbody, Will. “Ireland Not among 130 Countries to Back Global Corporation Tax Reform Deal.” RTE.Ie, 2 July 2021, www.rte.ie/news/business/2021/0701/1232531-global-minimum-corporate-tax-of-at-least-15-agreed.

- Driver, Julia. “The History of Utilitarianism.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 22 Sept. 2014, plato.stanford.edu/entries/utilitarianism-history.

- Nagle, Peter, and Naotaka Sugawara. “What the Pandemic Means for Government Debt, in Five Charts.” World Bank Blogs, 11 Jan. 2021, blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/what-pandemic-means-government-debt-five-charts.

- Romei, Valentina. “How the Pandemic Is Worsening Inequality.” Financial Times, 31 Dec. 2020, www.ft.com/content/cd075d91-fafa-47c8-a295-85bbd7a36b50.

- Guildea, Anna. “The G7 Global Minimum Corporate Tax Lacks Global Anchoring.” The Loop, 24 June 2021, theloop.ecpr.eu/the-g7-global-minimum-corporate-tax-lacks-global-anchoring.

- Cammeraat, Emile. “The Relationship Between Different Social Expenditure Schemes and Poverty, Inequality and Conomic Growth.” International Social Security Review, vol. 73, no. 2, 2020, pp. 101–23.

- Walla, Katherine. “The Case for a Global Minimum Corporate Tax.” Atlantic Council, 7 Apr. 2021, www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/the-case-for-a-global-minimum-corporate-tax.

- Willige, Andrea. “Corporate Tax Isn’t Working – How Can We Fix It, Globally?” World Economic Forum, 17 June 2021, www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/06/g7-corporate-tax-liability-emerging-economies-covid-19.

- Kambayashi, Satoshi. “Twilight of the Tax Haven.” The Economist, 5 June 2021, www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2021/06/03/twilight-of-the-tax-haven.

- Wier, Ludvig. “Tax Havens Cost Governments $200 Billion a Year. It’s Time to Change the Way Global Tax Works.” World Economic Forum, 27 Feb. 2020, www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/02/how-do-corporate-tax-havens-work.

- Bunn, Daniel. “A Global Minimum Tax and Cross-Border Investment: Risks & Solutions.” Tax Foundation, 22 July 2021, taxfoundation.org/global-minimum-tax.

- OECD Public Affairs Division, “Tax Effects on Foreign Direct Investment”. OECD Policy Brief, 2008.

- Gechert, Sebastian, and Philipp Heimberger. “Do Corporate Tax Rates Boost Economic Growth.” Macroeconomic Policy Institute – Working Paper, vol. 210, 2021.

- Wilkie, Christina. “130 Nations Agree to Support U.S. Proposal for Global Minimum Tax on Corporations.” CNBC, 1 July 2021, www.cnbc.com/2021/07/01/nations-agree-to-support-us-proposal-for-global-minimum-tax-on-corporations.html.

- Thériault, Annie. “OECD Inclusive Framework Agrees Two-Pronged Tax Reform and 15 Percent Global Minimum Tax: Oxfam Reaction.” Oxfam International, 9 July 2021, www.oxfam.org/en/press-releases/oecd-inclusive-framework-agrees-two-pronged-tax-reform-and-15-percent-global-minimum.

- “G7 Agrees ‘historic’ Minimum Corporate Tax Rate.” DW.COM, 5 June 2021, www.dw.com/en/g7-agrees-historic-global-minimum-corporate-tax-rate/a-57786417.

- Readhead, Alexandra, et al. “The End of Tax Incentives: How Will a Global Minimum Tax Affect Tax Incentives Regimes in Developing Countries? – Investment Treaty News.” International Institute for Sustainable Development, 24 June 2021, www.iisd.org/itn/en/2021/06/24/the-end-of-tax-incentives-how-will-a-global-minimum-tax-affect-tax-incentives-regimes-in-developing-countries.

- Wheatley, Jonathan, and Emma Agyemang. “Biden’s Global Tax Plan Could Leave Developing Nations ‘next to Nothing.’” Financial Times, 10 May 2021, www.ft.com/content/9f8304c5-5aad-4064-9218-54070981fb4d.

- Protto, Carlos, et al. “Perspectives on the Progress of Global Corporate Tax Reform.” International Centre for Tax and Development, 23 July 2021, www.ictd.ac/blog/perspectives-progress-global-corporate-tax-reform-inclusive-framework-beps.

- ATAF Communication. “130 Inclusive Framework Countries and Jurisdictions Join a New Two-Pillar Plan to Reform International Taxation Rules – What Does This Mean for Africa?” African Tax Administration Forum, 1 July 2021, www.ataftax.org/130-inclusive-framework-countries-and-jurisdictions-join-a-new-two-pillar-plan-to-reform-international-taxation-rules-what-does-this-mean-for-africa.

- “Experts Outline Possible Global Minimum Corporate Tax Impacts | News | SDG Knowledge Hub | IISD.” SDG Knowledge Hub, 23 June 2021, sdg.iisd.org/news/experts-outline-possible-global-minimum-corporate-tax-impacts.

- Independent Commission for the Reform of International Corporate Taxation. “International Corporate Tax Reform: Towards a Fair and Comprehensive Solution”. ICRICT, 2019.

- OECD, “Tax Policy Reforms 2018: OECD and Selected Partner Economies”, OECD Publishing, 2018.

- Ovonji-Odida, Irene, et al. “Assessment of the Two-Pillar Approach to Address the Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalization of the Economy”. South Centre Tax Initiative’s Developing Country Expert Group, 2020.