Ethics Review: DOL Fiduciary Rule

By Louisa Cook

The 2015 DOL Fiduciary Rule

The U.S. Department of Labor’s (DOL) so-called ‘Fiduciary Rule’, proposed by the Obama administration in 2015, required retirement advisors and stockbrokers act in the best interests of their clients and put their clients’ interests above their own. The rule expanded the definition of ‘investment advice fiduciary’, under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) of 1974, elevating all financial professionals working within retirement plans or providing retirement planning advice to a fiduciary status. The rule intended to eliminate any room for advisors and brokers to conceal conflicts of interest and required clearer disclosures of all fees and commissions received on retirement advice and plans.

The ERISA’s Fiduciary Standard Test, released in 1975, provided a narrow definition of the fiduciary rule, materially limiting the scope of what could be considered fiduciary advice. Consequently, loopholes remained, excluding many retirement advisors, brokers and insurance agents from a fiduciary standard. Previously, only advisors who charged a fee for their services on retirement plans and provided ongoing advice, as opposed to ‘one-time’ recommendations or solicitations, could be considered fiduciaries. According to a report by the White House Council of Economic Advisers, this has allowed investment companies to collect an additional $17 billion dollars annually in conflict of interest fees from American workers. A conflict of interest occurs when an individual or entity’s vested interests (such as money, status, knowledge or reputation) raise the question of whether their judgements, activities and/or decision making can be impartial. Hence, conflict of interest fees refers to fees collected by investment companies that result from financial advisors or brokers knowingly advising clients to purchase financial products not in their best interests (too risky, too expensive or unaligned with stated objectives), yet earn the advisor or broker a higher commission.

This article supports the backbone of the Fiduciary Rule, as it ensures incorporation of ethical practice into the broker profession and prevents brokers from collecting billions of dollars annually worth of conflict-of-interest fees. The current standard of ‘suitability’ is inadequate, as the commission-based model creates an ethical issue the vague term fails to address. The standard, on the other hand, produces considerable leeway for unethical behaviour by brokers managing retirement accounts. Society may tolerate a degree of unethical conduct as a by-product of the capital raising process. Nevertheless, it is vital to reduce harm to investors through appropriate disclosure of, and consent to conflicts of interest. Employing an utilitarian analysis, it is unclear whether the benefits of introducing the 2015 Fiduciary Rule outweigh the costs. As such, it is uncertain whether the proposal maximises the overall good and, consequently, whether it should be instituted. A utilitarian analysis, nonetheless, establishes grounds for further revision of, and improvement to the rule. Further revision of, and improvement to the rule is necessary to derive an accurate quantification of the true costs and benefits of the rule and to instil more certainty for the brokerage industry, potentially decreasing costs in the long run. The DOL, under the Biden administration, ought to revise the ambiguous provisions contained in the 2015 proposal and establish precise requirements that guarantee consistent interpretations of the rule by brokerage firms and registered investment advisors (RIAs).

Court Ruling Vacating the Fiduciary Rule

The rule was abruptly vacated in its entirety in a 2-1 decision by the fifth circuit of the US Court of Appeals on the 15th of March 2018, reversing a lower District Court’s decision that upheld the measure in Texas, Louisiana and Mississippi. The plaintiffs included the US Chamber of Commerce, the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association and the Financial Services Institute. The court ruled the DOL overstepped its statutory authority under ERISA, labelling the rule an “arbitrary and capricious exercise of administrative power”. The court also declared the rule “unreasonable”, for example, the Department’s broadening of what is deemed financial advice and who may provide it. The Court of Appeals denied a motion by the AARP and the State Attorney Generals of New York, Oregon and California to intervene in the case. The vacatur became effective on June 21, 2018, when the Fifth Circuit issued its mandate and the Fiduciary Rule was no longer part of federal law. The original 2010 proposal and the DOL’s 2015 re-proposal both received high volumes of comment letters and letters to legislators. Consumer advocacy groups generally favoured implementing the rule, whilst financial institutions consistently opposed it.

History of the Court Ruling

The DOL first proposed closing the ERISA’s loopholes in 2010. The DOL’s proposal extended the definition of investment advice, providing that any investment advice, even if it was a one-time recommendation, would be held to a fiduciary standard. The financial industry eventually lobbied to discard the proposal, as critics discovered extensive flaws in the DOL’s cost-benefit analysis and urged the DOL to pursue other means for implementation. The DOL withdrew the proposal in September 2011.

President Obama, on February 23, 2015, called on the DOL to revise the rules and regulations governing financial advisors’ practices. On April 8, 2016, the Fiduciary Rule was published in the federal register and deemed effective on June 7, 2016, with a delayed applicability date of April 10, 2017. The delayed applicability date allowed financial services companies to prepare for implementation. On June 1, 2016, eight prominent trade and industry groups filed a lawsuit against the DOL in Texas, claiming that the DOL surpassed its statutory authority under ERISA. The District Court in Texas upheld the DOL’s fiduciary rule. Two months following the publication in the federal register, the Republican-held House and Senate passed resolutions overturning the rule. President Obama successfully vetoed the Congressional attempt to block the rule.

The change in administration was instrumental to the regress of the Fiduciary Rule. Subscribing to a Washington cliché, that the easiest way to eliminate a federal rule is to delay it, Donald Trump signed an executive order forcing the DOL to delay the rule until June 2017. The order also required the DOL to review the regulations potential adverse impact on product pricing, investor protection and litigation. In March 2017, Vanguard and BlackRock, the world’s two largest asset managers, requested a further significant delay, due to the confusion surrounding the particulars of the rule and the final dates. The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) then issued a 60-day delay to the applicability date. On June 30, 2017, the DOL reopened the public comment period for the proposed rule for an additional 30 days. The district of Minnesota suggested an 18-month delay to the rule’s compliance deadline in August 2017. The proposal was filed as a court document in a lawsuit in the US District Court. The OMB approved the delay and changed the deadline, once again, to July 1, 2019. Before full implementation could occur, however, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, based in New Orleans, vacated the 2015 Fiduciary Rule.

The Ethics of Suitability

Brokers, planners and insurance agents, who work within retirement plans and accounts that do not satisfy ERISA’s 1975 definition of a fiduciary standard, are obliged to follow a legal and ethical requirement to recommend ‘suitable’ investments to their clients, the so-called suitability standard. According to the FINRA Conduct Rule 2111, ‘suitable’ recommendations require two criteria. Firstly, the broker must possess a reasonable basis to believe the recommendation is suitable, based on relevant information regarding the client’s ‘investment portfolio’. Additionally, the broker must reasonably believe the client possesses adequate information and an ability to assess the recommendation and derive an independent conclusion.

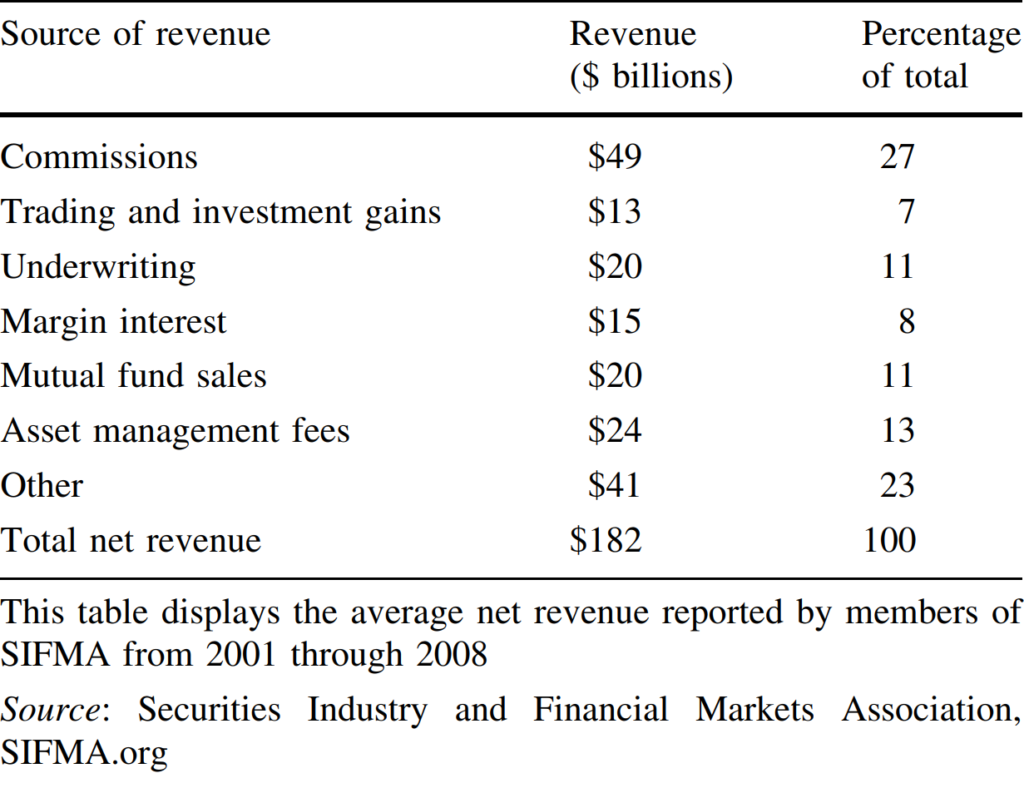

The commission-based model creates an ethical issue. Issuers depend on distribution channels within the financial services industry to market their securities and raise capital. The commission-based structure provides incentives for brokers, through the distribution channel, to conduct marketing for issuers. The ethics issue arises when an advisor may suggest the investment that yields the highest commission, over an investment that yields a lower commission but is potentially more ‘suitable’. The advisor chooses personal profit over the best interest of the customer. Table 1 displays the average total net revenue for U.S. financial firms from 2001 to 2008. On average, U.S. financial firms received a total of $49 billion in commissions, accounting for approximately one quarter of their total revenue.

Source: Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association

The suitability requirement holds the product isn’t defective. The broker provides a solution to the client’s financial problem- this does not necessarily mean it is the best solution. According to Barbara Roper, the director of Investor Protection at the Consumer Federation of America, an advisor satisfies a suitable recommendation through “recommending the worst of what’s suitable”. Since brokers only receive payment once a transaction is executed, they have a natural incentive to recommend investments that may not be in the best interest of their client. It is incorrect to assume all transactions involving commissions directly lead to unethical behaviour. Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge the incentives and opportunities the commission-based model creates.

The suitability standard fails to address this potential ethics problem. The vague language contained in the suitability standard paves the way for unethical broker behavior. Brokers must believe, on a ‘reasonable’ basis, the recommendation is suitable, based on relevant information about the client’s investment portfolio. The use of ‘reasonable’ suggests a standard. Yet, the specificities of this standard is open to broker interpretation. The way brokers evaluate the suitability of an investment strategy is dependent on their scope of reasonability. This scope may vary from aligning with one facet of a client’s investment portfolio, to the entire profile. Hence, a broker’s definition of ‘reasonable’ may rationalise a subpar investment recommendation. The suitability rule assumes the client’s capability to independently assess the advice provided. Although a client may possess a certain capability to assess investment recommendations, the final barrier to unethical practice should not be dependent on the individual who is seeking professional advice; considering the client’s vulnerable position, particularly in fully managed Investment Retirement Accounts (IRAs).

The suitability standard allows considerable leeway for self-interested investment advice by the broker. This behavior is justified by the ‘neoclassical economic rationale’, which assumes it is human nature to act in one’s own interests. The purpose of business in the economic system, according to this theory, is profit maximisation above all else. If neoclassical economics is accepted as truth, there is no basis to expect a fiduciary standard of care from the broker profession, to act in the best interests of one’s client, as opposed to one’s self. Neoclassical economic theory, which eliminates ethics from professional practice altogether, is flawed. Businesses, like other institutions, are social constructs that derive power and legitimacy to conduct their activities from society. Therefore, businesses in the financial industry, possess a social responsibility to conduct their activities in a way that benefits society as a whole and avoids inflicting harm.

Cost-Benefit Analysis of the Fiduciary Rule

Analysing the costs and benefits of imposing a fiduciary standard on brokers managing retirement accounts, constitutes a utilitarian analysis. Would requiring brokers to adhere to a fiduciary standard yield net benefits to investors, or restrain the efficiency of the industry? If benefits to investors outweigh costs to the brokerage industry, the introduction of a fiduciary standard is ethically justified.

The DOL acknowledged the difficulty of quantifying the benefits and costs associated with eradicating conflict of interest fees. Alternatively, the DOL emphasised the qualitative benefits of imposing a Fiduciary Rule, asserting that given the value of assets at stake in ERISA plans, even a small value improvement in a modest number of plans will likely result in significant economic benefits.

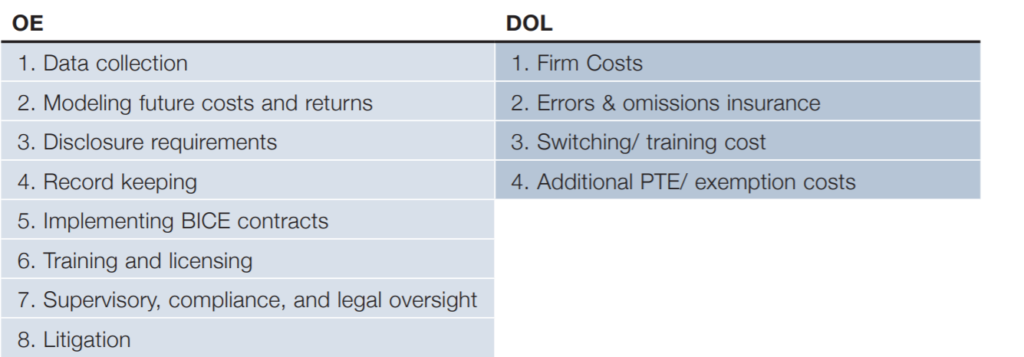

Oxford Economics (OE) conducted a thorough cost analysis of proposed regulations on broker-dealer firms, employing eight cost categories. The Financial Services Institute (FSI), an organisation representing independent financial services firms and financial advisors, provided financial support for the study and conducted it under contract with OE. FSI was one of the plaintiffs in the 2018 decision, by the Court of Appeals, vacating the fiduciary rule. Accordingly, the study is unlikely objective. Although this fact does not dismiss the validity of the study, it is important to acknowledge the incentives behind the data presented. Each cost category is listed in Table 2, alongside the four categories the DOL’s cost analysis included.

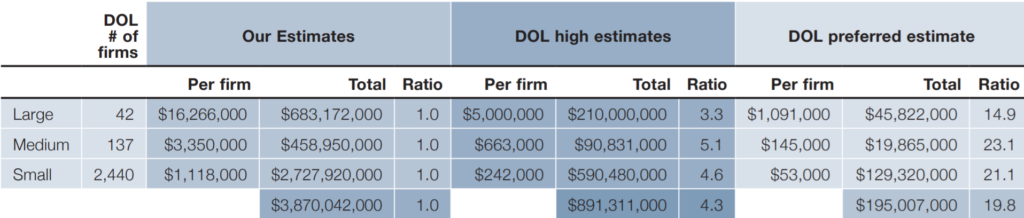

OE conducted detailed interviews and cost surveys with independent broker-dealer firms which would be most affected by the imposition of the Fiduciary Rule. OE concluded the proposed Fiduciary Rule would result in start-up costs ranging from $1.1 million to $16.3 million per firm, contingent upon firm size. Table 4 displays the average start-up costs by firm size, alongside the DOL’s estimates for comparison. OE estimates exceed the Department’s cost calculations for small, medium and large firms, by significantly higher margins. Specifically, 4.6 times as high for small firms, 5.1 times as high for medium firms and 3.3 times as high for large firms.

OE recognized that costs associated with the proposed rule would likely pass onto investors in the form of higher fees for services. Specifically, cost burdens imposed on broker-dealers would force firms to shift their business model towards fee-based advising and imposing a minimum balance for client accounts. Consequently, account minimums would result in small investors losing access to financial advisers or robo-advice accounts.

A study conducted by Oliver Wyman, estimated that 7.2 million IRA account holders would lose access to advisory services due to account minimums. Only investors possessing substantial assets would have access to financial advisors. Minority and single parent households tend to possess low or moderate net worth. Brokers provide invaluable financial advice to investors. Limiting access to such advice would adversely impact households which require it most. This outcome potentially exacerbates America’s wealth inequality, as low and moderate net-worth investors lose access to invaluable financial advice during market downturns.

Wyman asserted that 98% of small investors (classified as holding IRA accounts with $25,000 or below) possess a brokerage relationship. The DOL strongly refuted the claim the rule would result in small account holders losing access to financial advice. Rather, the Department claimed the new rule would promote innovation in the so-called ‘robo-advising’ services. OE’s interviewees were uncertain whether robo-advising would produce the same types of benefits investors receive from investment advisers. OE acknowledged that robo-investing may displace traditional investment models. Notwithstanding, OE acknowledged the success of the Fiduciary Rule is dependent upon an untested model.

OE further argued the proposal’s vague definitions and interpretations produced significant uncertainty for the brokerage industry. Any transactions, in which a financial advisor possessed a conflict of interest, would be termed ‘Prohibited Transactions’ (PT). In order to execute the transaction, an advisor required a ‘Prohibited Transaction Exemption’ (PTE). The most significant PTE was the ‘Best Interest Contract Exemption’ (BICE). If the advisor wished to continue operating on commission, in circumstances where a conflict of interest could exist, they would need to provide clients with a BICE. This guaranteed the advisor would act in the undefined ‘best interest’ of the client. The contract included vague provisions such as not receiving ‘excessive’ compensation. The Department failed to specify the precise criteria firms would be required to abide by in its Regulatory Impact Analysis. Notably, such contracts would be enforceable via state contract law courts. This suggested possible unforeseeable litigation costs.

In surveys, OE discovered that the utmost concern amongst broker-dealer firms was potential litigation costs. OE excludedlitigation costs in its estimates, as litigation risk is too difficult to quantify. The full cost of uncertainty, caused by the vague requirements in the rule, may outweigh litigation costs, as firms waste resources and sacrifice opportunities due to the risk of litigation. OE consulted with FSI’s lawyers and believed it was not misrepresenting likely interpretations of the rule by brokerage firms. The report, on the other hand, reflected an economic analysis, not a legal analysis. It purely reflected comments by brokerage firms and RIAs that would be impacted by the fiduciary rule.

It remains unclear whether the benefits of the proposed fiduciary standard outweigh the costs and vice versa. Advocates claimwhilst the exact benefits remain difficult to quantify, the economic harm, resulting from the advice provided under the suitability standard, amounts to billions of dollars annually. Imposing a fiduciary standard on brokers could generate significant investor savings.

Opponents claim the benefits do not necessarily outweigh the costs; broker-dealer firms will pass increased compliance costs onto investors, limiting access to investment accounts and reducing retirement savings overtime. To date, no clear consensus exists on the economic benefits and costs of the DOL Fiduciary Rule. This is because the costs and benefits prove difficult to measure, data is scarce (given the rule was never fully implemented) and various studies remain open to extensive criticism. The DOL’s cost-benefit analysis, for example, was critiqued by OE for failing to analyse all types and aspects of impacted accounts.

The objectivity of OE’s cost-benefit analysis, the main rejoinder to the DOL’s cost-benefit analysis, remains in question, given the study was funded by the FSI. The interviews reflect the concerns of brokerage firms and RIAs, the interests of whom FSI represent. The report failed to interview individuals or groups representing consumer interests, such as the Consumer Federation of America. The study’s biased nature therefore emphasises the potential costs of introducing the 2015 proposal to the brokerage industry and disregards its potential benefits to investors. Despite possible bias, it is difficult to justify imposing the 2015 fiduciary standard on brokers using a utilitarian calculation.

Justifying a Fiduciary Standard

In principle, this article supports imposing a legal and ethical obligation on brokers managing retirement accounts to act as fiduciaries. Brokers collect billions worth of conflict of interest fees annually under the suitability standard. Forcing brokers to disclose conflicts of interest will provide investors an opportunity to understand how conflicts may affect the advice they receive, and the ability to deliver informed consent or take their business elsewhere. These disclosures are vital because of the complexity of modern financial markets and investing, the potential damage that arises from possible broker misconduct, and the lack of knowledge, skills and experience of the average person.

The suitability standard assumes a client’s ability to assess recommendations and derive impartial conclusions. Instead of the possible victim of misconduct, the last impediment to unethical behavior should be the individual who fully understands the situation and therefore holds a degree of professional authority – the broker. A survey conducted by Infogroup revealed that 66% of 1,319 investors incorrectly believed stockbrokers owed fiduciary duties to their clients. According to Arthur B. Laby, the Co-Director of the Rutgers Center for Corporate Law and Governance, the public’s reasonable expectations justify placing a fiduciary obligation on broker-dealers providing personalised investment advice. Advertisements and titles used by brokerage firms, replete with advice language, he argues, suggest a relationship of agency. The section 913 study discovered that titles used by brokerage firms, such as ‘financial advisor’ and ‘financial consultant, suggest the broker provides investment advice. Further, use of such titles impacted clients, as respondents equated them to an investment adviser, rather than a broker-dealer. From a legal perspective, the way broker-dealers market their services as advisory, grounds a reasonable expectation they will operate under a fiduciary standard.

Imposing a fiduciary standard on brokers is a cultural shift towards incorporating greater transparency and ethical practice within the financial industry. The DOL’s 2015 Fiduciary Rule requires significant revision of its cost-benefit analysis and ambiguous requirements. The Rule produced uncertainty for the brokerage industry, given its lack of clear definitions and interpretations. The DOL maintained giving broad definitions provided broker-dealer firms flexibility. In OE’s study, firms perceived the vagueness as a potentially costly lack of clarity.

Nevertheless, US companies consistently fight new regulations by providing worst-case scenarios to defend their profits, at the expense of defending their clients.

OE’s study likely replicates a worst-case scenario, considering the FSI’s incentives to defend the profits of brokerage firms and RIAs, whose interests they represent. In Chapter 7 of the Department’s Regulatory Impact Analysis, the DOL suggests ‘regulatory alternatives’. For example, the DOL recommended issuing a prescriptive, as opposed to a contractual PTE. This offers specific criteria for broker-dealers to satisfy, as opposed to relying on the vague standards contained in the BICE. A further revision of, and improvement to, the 2015 DOL Fiduciary Rule is necessary to derive an accurate quantification of the true costs and benefits of the rule. Additionally, a good revision will create more certainty for the brokerage industry, thereby reducing firm costs in the long run. The DOL, however, is likely correct in asserting that the drastic costs associated with the rule is an expected repercussion of implementing any large-scale regulation, that will inevitably benefit millions of investors by diverting conflict of interest fees towards higher-quality investments, gradually increasing retirement savings overtime.

A Fiduciary Rule Under a Biden Administration

As the Biden administration enters office, it is likely efforts to revisit the Fiduciary Rule altered under the Trump administration, will take place through congressional and/or administrative action. In June 2020, the DOL proposed a new Fiduciary Rule, reinstating the 1975 ‘five-part test’, which provided a narrow definition of fiduciary advice. It also put forward a new class exemption from certain prohibited transactions under ERISA and the internal revenue code. The five-part test applies only to the provision of investment advice for a fee and advice received on a regular basis.

The Democratic Party, in a draft version of its 2020 policy platform, stated that financial advisers should be “legally obligated to put their client’s interests first”. They further asserted they would “take immediate action to reverse the Trump administration’s regulations allowing financial advisers to prioritise their self-interest over client’s financial wellbeing”. President Biden nominated Boston mayor, Marty Walsh, as Labor Secretary. Walsh previously served as a Massachusetts state representative and union official. In his legislative role, he was a liaison to the Massachusetts unions on labor policy issues. If confirmed by the Senate, he will likely push the DOL in a progressive direction.

Given President Biden was Vice President when the Obama administration advanced the 2015 proposal, he may adopt a similar proposal. During testimony before the House Financial Services Committee in May, Gary Gensler , Chair of the US Securities and Exchange Commission, said it is important “investors actually have brokers take their best interest at heart and that’s what we’re going to do through examination and enforcement, (and) guidance to ensure that that rule is fully complied with as written.”

Although the DOL’s proposal was flawed in its economic impact on the industry, the imposition of a fiduciary standard on brokers managing retirement accounts is both warranted and necessary to address conflicts of interest in retirement accounts. The DOL, under the Biden administration, should revise the ambiguous provisions contained in the 2015 proposal and put forward more precise requirements for brokerage firms and RIAs. The establishment of precise requirements will likely guarantee consistent interpretations of the rule by brokerage firms and RIAs and offer more certainty for the industry.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Angel, James J., and Douglas McCabe. “Ethical Standards for Stockbrokers: Fiduciary or Suitability?” Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 115, no. 1, pp. 183-193. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23433913?seq=1. Accessed 8 December 2020.

Beilfuss, Lisa. “Fiduciary Rule Dealt Blow by Circuit Court Ruling”. The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company Inc., 15 March 2018. Web. 9 December 2020. www.wsj.com/articles/fiduciary-rule-dealt-blow-by-circuit-court-ruling-1521164915

Boms, Steve. “The SEC’s Proposal Likely Doesn’t Signal the End of Washington’s Fiduciary Drama.” Journal of Financial Planning, vol. 31, no. 8, 2018, pp. 25-27. ProQuest, search-proquest-com.ezproxy.library.uwa.edu.au/trade-journals/secs-proposal-likely-doesnt-signal-end/docview/2110462511/se-2?accountid=14681. Accessed 15 December 2020.

Donachie, Patrick. “DOL Reveals Revised Fiduciary Rule.” WealthManagement.com. Informa USA, Inc., 29 June 2020. Web. 14 December 2020. www.wealthmanagement.com/regulation-compliance/dol-reveals-revised-fiduciary-rule

“Five Key Points About the DOL’s New Fiduciary Rule.” Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance. Harvard Law School, 28 July 2020. Web. 10 December 2020. corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2020/07/28/five-key-points-about-the-dols-new-fiduciary-rule/

Frankenfield, Jake. “What Is a Robo-Advisor?” Investopedia.com. Dotdash, 28 March 2020. Web. 9 December 2020. www.investopedia.com/terms/r/roboadvisor-roboadviser.asp

Freeman, David F., et al. “DOL’s Fiduciary Rule Vacated- But the Best Interest Concept Appears Here to Stay.” Arnold and Porter. Arnold and Porter, 9 July 2020. Web. 16 December 2020. www.arnoldporter.com/en/perspectives/publications/2018/07/dols-fiduciary-rule-vacated-but-the-best-interest#:~:text=On%20appeal%2C%20the%20US%20Court,unreasonable%22%20and%20an%20%22arbitrary%20and

“How a Biden Win in November Reshapes Investment Advice Rules.” Institute for the Fiduciary Standard, 15 September 2020. Web. 11 January 2021. thefiduciaryinstitute.org/2020/09/15/biden-administration-reforms-fiduciary-rule/

Laby, Arthur B. “Selling Advice and Creating Expectations: Why Brokers Should be Fiduciaries.” Washington Law Review, vol. 87, No. 3, 2012, pp. 707-776. Digital Commons, digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wlr/vol87/iss3/4/. Accessed 12 December 2020.

Lake, Rebecca. “Can the Fiduciary Rule Be Saved?” Investopedia.com. Dotdash, 25 June 2019. Web. 10 December 2020. www.investopedia.com/news/can-fiduciary-rule-be-saved-0/#:~:text=The%20Latest%20on%20the%20Fiduciary,Income%20Security%20Act%20(ERISA)

Meyer, Anne. “With a New Administration, Will the Department of Labor’s Fiduciary Rule Once Again be Revised?” JD Supra. Snell & Wilmer, 20 November 2020. Web. 11 January 2021. www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/with-a-new-administration-will-the-46273/

Ohashi-Sides, JulieAnne. “Ethical Standard for Stockbrokers in the United States: An Ethical Analysis of the Suitability and Fiduciary Standards.” Digital Commons. Western Oregon University, June 2020. Web. 13 December 2020. digitalcommons.wou.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1222&context=honors_theses.

Penn, Benjamin, et al. “Biden Names Boston Mayor Walsh to Head Labor Department.” Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg, 8 January 2021. Web. 11 January 2021. bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-01-07/biden-names-boston-mayor-walsh-to-head-labor-department

Rubin, Douglas Gary. “Advisers and the Fiduciary Duty Debate.” Business and Society Review, vol. 120, no. 4, 2015, pp. 519-548. Wiley Periodicals, Inc, https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.uwa.edu.au/10.1111/basr.12073. Accessed 14 December 2020.

Segal, Troy. “Conflict of Interest.” Investopedia.com. Dotdash, 1 December 2020. Web. 10 January 2021. www.investopedia.com/terms/c/conflict-of-interest.asp

Silver, Caleb, et al. “Everything You Need to Know About the DOL Fiduciary Rule.” Investopedia.com. Dotdash, 19 December 2019. Web. 8 December 2020. www.investopedia.com/updates/dol-fiduciary-rule/#:~:text=Under%20a%20fiduciary%20standard%2C%20financial,simply%20finding%20%E2%80%9Csuitable%E2%80%9D%20investments.&text=This%20was%20to%20guarantee%20that,best%20interest%20of%20the%20client.

“The Economic Consequences of the US Department of Labor’s Proposed New Fiduciary Standard.” Oxfordeconomics.com. Oxford Economics, 18 August 2015. Web. 17 December 2020. www.oxfordeconomics.com/recent-releases/the-economic-consequences-of-the-us-department-of-labor-s-proposed-new-fiduciary-standard

“The Effects of Conflicted Investment Advice on Retirement Savings.” Executive Office of the President, Council of Economic Advisors, February 2015. Web. 17 December 2020. permanent.fdlp.gov/gpo55500/cea_coi_report_final.pdf

United States, Congress, House, Subcommittee on Health, Employment, Labor and Pensions, Committee on Education and the Workforce. “Redefining ‘Fiduciary’: Assessing the Impact of The Labor Department’s Proposal on Workers and Retirees.” The Superintendent of Documents. United States Government Printing Office, 26 July 2011. Web. 12 December 2020. www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-112hhrg67444/pdf/CHRG-112hhrg67444.pdf

“Utilitarianism.” Sevenpillarsinstitute.org. Seven Pillars Institute for Global Finance and Ethics, 3 October 2010. Web. 9 December 2020. sevenpillarsinstitute.org/utilitarianism/