The Ethics of China’s Zero Covid Policy

Guangqian Shine Yang

Introduction

On June 1, 2022, fireworks went up in the skies over Shanghai (GT Staff Reporters). Residents of Shanghai celebrated the regained freedom after a two-month citywide lockdown. For many, it was like welcoming the new year: full of hope for the return to normal life. Yet less than two weeks later, more districts again plunged into lockdowns as positive cases picked up, and the Financial Times reports the same measures may continue into 2023 (Bloomberg; Alim, White and Lin). The lockdown in Shanghai is one instance of China’s broader Zero Covid Policy: spotted before in other Chinese cities such as Changchun, Jilin, and Xuzhou, it is now also seen in Beijing (Bloomberg News).

In evaluating the ethical implications of the recent policy responses in Shanghai, this article also applies itself to China’s policy response to the Omicron outbreak in general. The policy has lost legitimacy amongst some parts of the public as people have borne the cost of lockdown to various extents. The perceived legitimacy of a policy is partially founded upon its ethical justification, thus in investigating the policy’s ethical status, this article also has implications over its legitimacy (Fabienne). China’s Zero Covid policy is ethically flawed for its cost-inefficiency, lack of respect for truth, and disregard for people’s freedom in implementation. Although the lockdown was implemented by local authorities instead of the government per se, the government is still ethically responsible for the implementers’ conduct, as the implementation failures are inevitable given the wider policy environment. Thus, this article also concerns itself with the ethical implications of the policy implementation.

China’s Zero Covid Policy and Shanghai’s Lockdown

High Level Policy Direction

The Zero Covid policy aims to eliminate all COVID-19 cases in the region, as opposed to coexisting with the virus. The fundamental assumption and justification for Zero Covid is that infection has severe health consequences. China has adopted the ‘Dynamic Zero’ approach, which involves precisely identifying a source of infection via regular mass testing and containing infection by contact tracing and mandatory isolation (J Liu, M Liu and Liang 74). The Chinese government claims the ‘Dynamic Zero’ approach is desirable for minimizing the pandemic’s impact on the wider economy and people’s normal lives (J Liu, M Liu and Liang 74). To achieve Zero Covid, the policy must be implemented at speed, because it gets increasingly costly as the variant spreads further. The time sensitivity of the policy thus gives rise to a related concept called ‘Societal Zero’, meaning there are no infected cases in unrestricted areas, namely, areas that are not in lockdown (Brant). Both ‘Dynamic Zero’ and ‘Societal Zero’ have been expressed as policy goals throughout the pandemic, and have subsequently shaped policy outcomes.

Shanghai’s Policy Response

In pursuance of the ‘Dynamic Zero’ policy, the Shanghai municipal government issued a citywide lockdown on the 30th of March 2022 (Palmer). Travel into and out of Shanghai stopped completely to prevent new foreign cases as well as spreading to other cities in China. All 26 million residents faced repeated mandatory mass testing to detect cases. Those testing positive and close contacts of the infected were sent to centralized quarantine facilities to stop the virus from spreading. Others underwent mandatory self-isolation at home, which varied in length depending on the circumstances one’s area was in: e.g. residents in areas without positive cases in the past 14 days could travel to the nearest streets, but if positive cases were reported in the area then all residents there saw their quarantine period extended by two weeks. During self-isolation, people are not allowed to leave their place for whatever purposes. Essentials such as food were centrally distributed from the rest of China. Public health workers would also disinfect households where positive cases had been reported. Most businesses, in-person schooling, transportation and deliveries were halted for the same purpose. Later on, some hospitals were also suspended (Shanghai Municipal Health Commission). With such rigorous measures, cumulatively, 63,179 people tested positive and 595 died from Covid in the past six months (JHU CSSE).

Shanghai’s Policy Implementation

Local authorities such as JuWeiHui (居委会) were put in charge for implementing the municipal government’s policy decisions. When first announced, the lockdown was to last no longer than two weeks (Zhang and Yan). The Shanghai Municipal government also claimed there would be no lockdown merely four days prior to the lockdown (Zhuang). As a result, most local authorities were unprepared, lacked coordination skills and capacity, and responded inadequately to people’s needs, especially early on during the lockdown. Some local authorities also went very far to meet policy goals, sometimes without regard for the residents experiencing policy outcomes. This is because China’s political institutions heavily rely on accountability to ‘above’, namely, higher levels of authorities. In comparison, civil society is relatively weak. The average citizen struggles to hold officers accountable as officers are supported by their superiors. This system resulted in a moral hazard problem during the lockdown, as local authorities don’t bear the cost of their own actions. Even when local authorities hoped to be accommodating, the rigidity of the system often stopped them from being so. During this fraught time, residents of Shanghai quickly formed self-help groups where neighbours shared resources and helped those in need. Yet, the limited capacity, moral hazard, and unaccommodating system led to the tragedies reported by ‘unofficial sources’ during the months of lockdown. For example[1]:

- Centralized quarantine sites were first put into use without having been fully constructed, with leaky roofs, no working toilets, and spoiled food (東森新聞 CH51);

- A pet dog was beaten to death on the street after its owner tested positive (Yeung);

- Local officers forced entry into homes to disinfect households where someone had tested positive (夏);

- Iron fences were put up at entrances and exits to residential blocks to force residents to stay at home, despite the fire risks associated with the blockade (Yip);

- Elderly and young children in desperate need of medical assistance were denied access to hospitals for not having valid reports of negative tests;

- Residents in self-isolation banged crockery in concert in the face of food shortages (Guardian News);

- Some were forcibly taken to centralized quarantine despite having turned negative after first testing positive;

- Newborns were forcibly separated from their carers if either party tested positive (Normile)

Some Shanghai residents organized an unofficial record of lockdown-induced deaths (‘上海疫情逝者名单(不完全统计210+位)’). The record included cases such as a public health worker committing suicide due to irreconcilable pressure, a nurse who died from asthma due to lack of treatment, and a security guard who passed away after overworking. The inexhaustive list contains more than 200 profiles.

Censorship and Propaganda

In short, the two-month quarantine induced much suffering directly on the Shanghai population. Yet, not everyone was equally affected. This allowed space for propaganda and censorship, employed to various extents by all governments, but especially prominent during China’s Covid response. For example, most articles reporting negative experiences during the lockdown were quickly taken down from social media. The viral video ‘Voices of April’ also underwent a battle of remembrance where the authorities repeatedly deleted it but citizens repeatedly reposted new links (‘Voices of April’ Shanghai, 4/2022 with English Subtitles). Reports state the word ‘lockdown’ itself is also banned now – instead, one is to use the phrase ‘static management-style suppression’(Davidson). Similarly, instances of propaganda were abundant, where the Zero Covid policy was lauded as the Chinese approach, and the Shanghai Municipal government sent a letter to all citizens celebrating how the lockdown successfully dealt with the Covid outbreak under Xi’s directives, despite the high costs borne by the residents (Normile; 薛).

Utilitarian Analysis

Most policy analyses resort to utilitarianism. Utilitarians define something as ethical if it maximizes total welfare. Classical utilitarianism such as that held by J.S. Mill takes welfare to mean pleasure, i.e., a certain positive emotional state (Brink). However, the subjective nature of pleasure makes it difficult to quantify, as well as to conduct interpersonal comparisons, which are essential qualities for policy analysis. For now, I interpret welfare as Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYs) and economic measures (e.g. GDP) for the sake of impartiality (Annemans;

Savulescu et al. 623). QALY is an apt measure for this analysis as it is commonly used to evaluate health-related interventions.

In practice, utilitarian analysis involves a counterfactual analysis combined with a cost-benefit analysis. In conducting a cost-benefit analysis of a policy, one calculates its net benefit, i.e., total benefit minus total cost, where benefit is synonymous to welfare. Often, when outcomes have not yet taken place, the cost-benefit analysis involves calculating expected net benefit. This means that both total benefit and total cost would be probability-weighted. A counterfactual analysis then requires us to ask the question: ‘What would’ve happened if this policy did not occur?’. It requires us to calculate the net benefit of the best alternative to the policy (whether it is another policy or the status quo) and compare it with the net benefit of the policy under question. The counterfactual analysis is necessary for considering the opportunity cost of a policy. Going through this process allows one to discover the welfare-maximizing policy.

Utilitarianism is desirable for ethical analyses for two reasons. Firstly, it is very practical, as demonstrated by the clear scheme of actions outlined above. Provided with sufficient evidence, for example with a powerful algorithmic simulator, utilitarianism has the beauty of simplicity, like a mathematical function. Secondly, utilitarianism is egalitarian at its core. It does not discriminate between the President’s welfare from your welfare: either could be sacrificed for the sake of increasing total welfare in the society. Such egalitarianism makes utilitarianism very intuitively plausible.

Utilitarianism is categorized into two categories by J.J.C. Smart: act utilitarianism and rule utilitarianism (9). Act utilitarianism is concerned with the welfare consequences stemming from the particular action itself, in this case, from the policy actions seen during Shanghai’s lockdown. On the other hand, rule utilitarianism is concerned with the welfare consequences of the said action being performed by everyone in like circumstances. The two often give disparate conclusions. For example, although in a particular instance a starving child stealing food from a shop may increase total welfare, if every starving person steals food, then the rule of law would be undermined, leading to a reduction in overall welfare. As the Covid response involves both particular actions taken (e.g., the decision to lock down) and long-standing policy conventions (e.g., propaganda and censorship), both types are looked at in this article. Viewed from both perspectives China’s Zero Covid policy is ethically flawed.

Act Utilitarianism – Cost Inefficiency

Central to the analysis is whether the lockdown was the most cost-efficient policy possible. Below is an evaluation of the benefits and costs of locking down Shanghai, and then proposed alternatives which appear to generate greater benefits at lower costs. As there exists such an alternative, the lockdown in Shanghai is not morally justified from a utilitarian perspective because it fails to maximize welfare. For argument’s sake, two alternatives are provided: 1) vaccinate and open up; 2) more considerate NPIs.

Benefits of Lockdown

The main benefit of Shanghai’s lockdown is the lives saved across China.[2] Utilitarians are not concerned with the lives themselves but the welfare – as measured by QALYs saved (Savulescu et al 627). For simplicity’s sake, this article focuses on QALYs saved from deaths prevented only, whereas in reality, severe cases could also significantly reduce one’s life expectancy even when cured.

QALYs saved by lockdown = (Life expectancy – average age at death) x number of deaths x discount factor for quality of life

= (76.9-74) x 1.55 million x 0.7 = 3.15 million

Using transmission patterns spotted in the 2022 Shanghai Omicron outbreak, a study published in Nature estimates that with a rapid booster vaccine roll-out (of the inactive type developed by China) but no lockdowns, across China there would be 1.55 million deaths within six months[3] (Cai et al.). This would be a 0.11% death rate.[4] The model also estimates that by the end of the six-month period infection tends to zero, therefore we are solely concerned with this period (Cai et al.). Within the 1.55 million deaths, 93.6% or 1.4 million are aged 60 and over (Cai et al.). Based on data from the Omicron outbreaks in Hong Kong and Shanghai, a conservative estimate for the average age at time of death is 74 years old (Kwan; Ma et al.). The World Bank reports that life expectancy in China is 76.9 years. Consequently, a total of 4.95 million life years would be lost without the lockdown. Due to reduced health in old age, assume the quality of life in the life years saved to be 70% of the quality of life experienced by individuals with perfect health (Kocot et al.). The final QALYs saved by Shanghai’s lockdown (compared to booster but no lockdown) would be 3.15 million.

Costs of Lockdown

The main costs of lockdown include costs of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs), such as mass testing and constructing quarantine facilities, as well as the economic costs due to lost trade, productivity, and unemployment. The lockdown-induced suffering of individuals is negligible (and hard to quantify) in the face of millions of QALYs, despite its more-than-real effects on people’s quality of life.

Regular mass testing contributes significantly towards the costs of NPI-implementation. Data from the recent lockdown in Shanghai is not readily available. However, by assuming the cost of testing to consist of wages for temporary testing workers and cost of testing kits, some estimate that to test every resident once every 48 hours for the duration of the lockdown (60 days) requires 273.2 million yuan (Luo and Wu). On top of that, to build and run the 62 temporary quarantine facilities employed during the lockdown, to disinfect public spaces as well as private properties (a questionable move as the chance of catching covid from a contaminated surface is 1 in 100,000), and other measures which data cannot be obtained for all incurred further implementation costs (Xinhua; Zhang et al.).

The economic costs are more profound. Firstly, a full-scale lockdown as the one adopted in Shanghai for a month is estimated to have caused a 2.7% fall in China’s real GDP[5], nearing $0.4 trillion (Chen et al.). Almost all economic activities in Shanghai were on pause for around two months, suggesting an upfront cost of near $0.8 trillion. This estimate does not include the lockdown’s effects on expectations, saving and investment decisions, which further depress economic growth. Secondly, Shanghai’s lockdown led to an uptick in unemployment. Though Shanghai-specific data is lacking, the national average reports a 0.1% increase in urban unemployment rate between March and May (Xinhua; Chen). Youths were hit particularly hard, with unemployment rate amongst those aged 16-24 years old reaching 18.2% in April, 1.4% higher than in 2020 (Chen). Unemployment has real welfare implications, as a study finds unemployed individuals to be more likely to experience poor health and early death (Roelfs et al.). Thirdly, globalization means Shanghai’s lockdown severely impacted the global economy, too: experts at Russell Group claim export and import trade disruptions during Shanghai’s lockdown led to a $28 billion loss in global trade. Finally, in responding to the economic hardship caused by the lockdown, Shanghai has issued an economic recovery bundle amounting to $22 billion, which greatly adds to its local budgetary debt (Ren and Zhang; ‘Shanghai: Govt Finance | CEIC’). Though this bundle helps alleviate some of the economic hardship due to business interruptions and may improve employment figures, its focus on tax rebates and low-interest loans means the residents hit the hardest during the lockdown – mainly migrant workers in low-paid service industries – may still be left unsupported (Huld and Zhou; Yu and Yang).

An Alternative – Vaccinate and Open Up

This is the strategy most countries in the world adopted by the time Omicron hit. For example, in Singapore, about 91% of its total population are vaccinated (Ritchie et al.). When Omicron landed in Singapore at the end of 2021, only minimal NPIs way short of a lockdown were adopted, for example, closed international borders, mandatory masking, and self-isolation for asymptomatic to mild cases (‘MOH | Past Updates on COVID-19 Local Situation’). The Singaporean Ministry of Health has emphasized vaccination throughout the past months.

With 87.2% of total population fully vaccinated, China has a high vaccination rate (Ritchie et al.). However, it has decided to adopt costly and extreme NPIs due to the lack of protection amongst its vulnerable groups. Consistent with international findings, a study[6] conducted during Shanghai’s outbreak finds that people aged 60 and over are at higher risk of death from Omicron (‘Who Is at High Risk from Coronavirus (COVID-19)’; Ma et al.). 42.6% of China’s over-60 population are unvaccinated (Olcott et al.). Yet due to the nature of China’s domestic vaccines, only three doses of vaccines would be 98% effective at preventing severe illness in the older population (Olcott et al.).

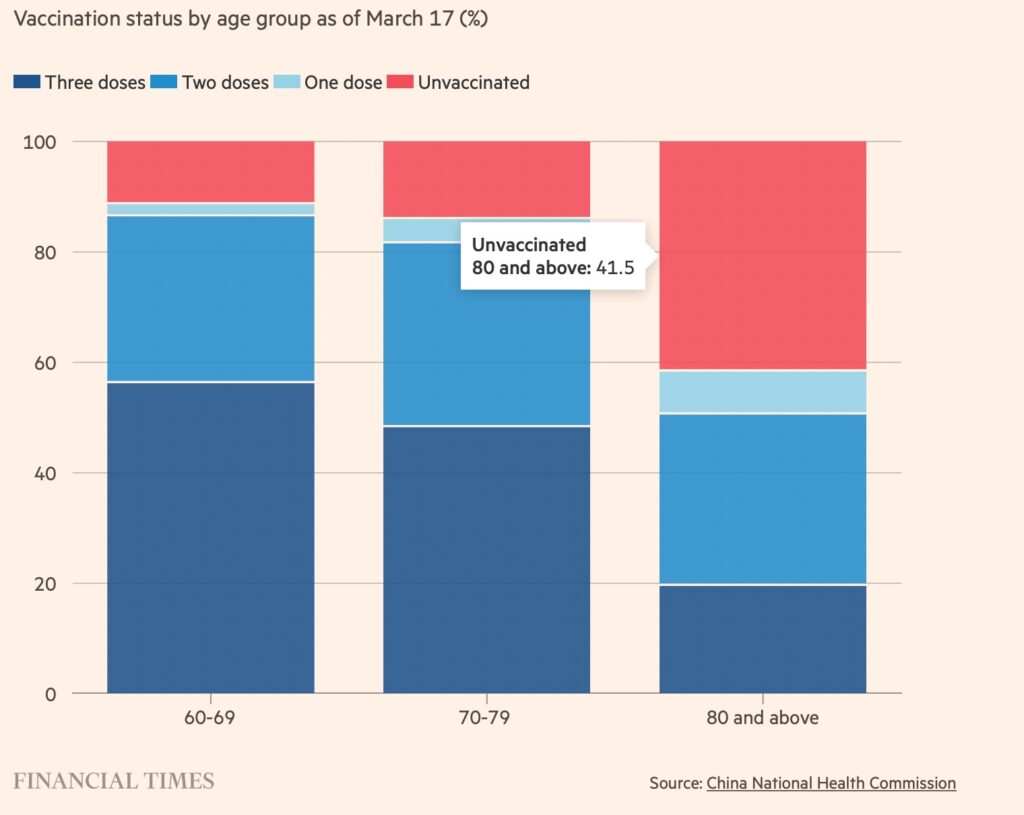

Figure 1: China’s vaccination rate amongst senior citizens

Source: Financial Times

Individual behaviours partially explain the low vaccine uptake amongst the aged: vaccine hesitancy due to potential side effects is more common amongst them, and China’s low incidence in the past two years leads to a false sense of safety (Olcott et al.). However, China’s Zero Covid policy is also partially to blame. Because the policy emphasizes zero infection instead of zero death from infection, China’s vaccination strategy throughout the past two years has largely focused on those with higher risks of infection – often those in work, as Zhengming Chen, a professor in epidemiology at Oxford University, states (Burki). China is now speeding up vaccination amongst the elderly by offering free vaccine insurance to all those aged 60 and over to combat vaccine hesitancy (Yu). But had it moved sooner, the costly lockdowns would not have been necessary.

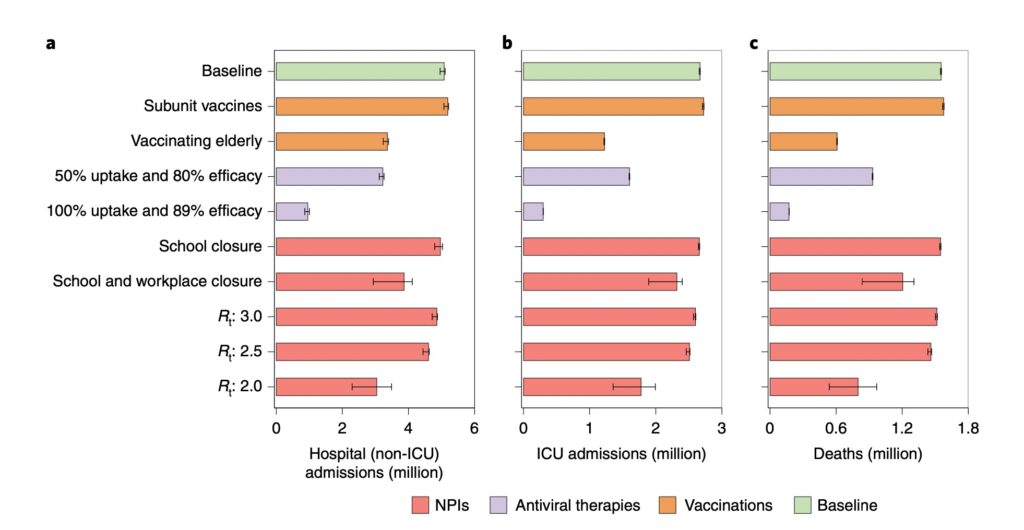

Figure 2: Hospital admissions, ICU admissions and Deaths under different scenarios

Source: Nature

From Figure 2, where the top bar labelled ‘Baseline’ indicates the aforementioned 1.55 million death nationwide, it can be seen that ‘Vaccinating elderly’ may reduce death by 0.95 million, to 0.6 million (Cai et al.). Assuming average age at time of death remains at 74, the total QALYs saved by this alternative is 1.93 million.

QALYs saved by vaccine = (Life expectancy – average age at death) x number of lives saved x discount factor for quality of life

= (76.9-74) x 0.95 million x 0.7 = 1.93 million

This may seem incomparable to the 600 deaths Omicron has caused China to date. Yet, a robust and well-targeted vaccination campaign combined with inexpensive and moderate NPIs such as those seen in Singapore is likely to save as many lives as the lockdowns implemented in China, evidenced by the fact that by end of March 2022, the Omicron virus in both countries had similar effective reproduction numbers (R) – a measure of the transmission rate of the virus (‘Updates to Health Protocols’; ‘Covid-19: Estimates for Singapore’; ‘Covid-19: Estimates for China’). Further, vaccination is less costly and more sustainable, especially because barring any significant further mutations in the virus, there is little need to vaccinate the population repeatedly in the face of a future wave, unlike with lockdowns.

As of March 2022, 52 million people aged 60 and over in China remain unvaccinated (Cai et al.). Assuming that on average every person requires 1.5 additional jab to be fully protected, this amounts to 78 million jabs. Though vaccines are provided for free to citizens, the maximum retail price is $10.5 per dose (CodeBlue). The cost of administering vaccines in China is unavailable. However, a study looking at costs of vaccine delivery in developing countries estimates vaccine administration to be $2.67 per dose, including the cost of campaign (Banks et al.). Thus, the total cost of this alternative is approximately $1.03 billion, less than 0.13% of the cost of Shanghai’s lockdown alone.

Comparing the costs and benefits of this alternative to that of locking down Shanghai, its superiority in terms of cost-effectiveness is obvious: with 0.13% of cost, it is capable of saving 60% of lives. Thus, China’s Zero Covid policy, in particular its lockdown measures as seen in Shanghai, is not ethically justified from a utilitarian point of view.

Perhaps one issue remains: what if the 0.6 million deaths under this alternative actually outweighs the 99.87% of cost saved? This is unlikely to be the case: EU Research finds that a QALY in the UK is worth $37,867 (Himmler). Assume a QALY in China is worth the same, the 0.6 million deaths are worth $46.12 billion in monetary terms, 5% of the cost of lockdown.

A Second Alternative – More Considerate NPIs

Some may take issue with the above analysis as it tries to assign a monetary value to life, or QALYs. However, Shanghai’s lockdowns and other similar lockdowns that constituted China’s Zero Covid policy can still be proven to be suboptimal in terms of cost-efficiency even without assigning a monetary value to life. Consider the 200 and counting deaths caused by Shanghai’s lockdown.[7] Any alternative adopting more considerate NPIs coupled with greater support for the residents could at least reduce the number of lockdown-induced deaths in Shanghai, without impacting the benefits yielded by the whole of China. Only minor and inexpensive adjustments need to occur for that to be possible. For example, allow residents experiencing asymptomatic to mild cases to self-isolate at home instead of taking them to quarantine centres; make emergency hospitals and pharmaceuticals readily available and relax requirements on negative test results for patients seeking emergency assistance; local residential blocks to relax entry and exit requirements for emergencies. Although some adjustments may not have been possible due to the unpreparedness the Shanghai Municipal government and local authorities were in at the beginning of the lockdown, the adjustments just listed require little resources. As these adjustments could have been possible and are more cost-effective than the lockdown seen in Shanghai, again the latter is shown to be not welfare-maximizing, thus ethically flawed from a utilitarian point of view.

Rule Utilitarianism – Lack of Respect for Truth

Act utilitarians seek to maximize welfare of their actions by collecting evidence and analysing effects of different options. There are some general rules they follow to ensure they find the optimal action. These rules are ethically desirable from the perspective of rule utilitarians because when followed they are most likely to lead to welfare-maximizing outcomes. For example, one such rule is to always update one’s beliefs when there is new evidence (Savulescu et al. 627).

However, some aspects of Shanghai’s lockdown and China’s Zero Covid policy in general have violated these rules, rendering them unethical from the rule utilitarian point of view. In particular, the censorship and lack of transparent communication prevalent during China’s lockdowns, as well as the inflexibility in the face of evidence constitute such a violation. Both display a lack of respect for truth, either in trying to obfuscate truth, or in not responding to it.

Censorship and Opaque Public Communication

Censorship or the lack of clear communication from the authorities to the public is not conducive to welfare maximization for the following reasons.

Firstly, by concealing something that has happened, one conceals evidence from which new conclusions may be made. Without access to such evidence, one cannot respond to it to maximize welfare. For example, early on in Shanghai’s lockdown, a shared spreadsheet was circulated amongst residents to organize voluntary help for those in need (for example, helping seniors obtain food). However, perhaps because it hinted at the inadequacy of government provisions, it was taken down from Weibo, the Chinese equivalent of Twitter. Censoring the shared spreadsheet made it more difficult for help to reach those in need, reducing their welfare. Such censorship also means the government has little incentive to learn from their mistakes, as few people remember their mistakes, let alone to hold them accountable.

Moreover, by obfuscating the truth in this manner, it may lead to distrust of the government amongst citizens. This is already seen when Beijing’s residents rushed to buy groceries when the government insisted that there was abundant food (‘The Way Chinese Think about Covid-19 Is Changing’). This is unfavourable for carrying out welfare-maximizing policies as it could eventually lead to an uncooperative civil society, thereby increasing the cost of implementation.

Evidence Insensitivity

China’s Zero Covid policy demonstrates its insensitivity to new evidence, especially evidence about its past mistakes. For example, the same kind of unaccommodating NPIs were seen in the 2020 Wuhan lockdown and similarly led to preventable deaths (‘The Way Chinese Think about Covid-19 Is Changing’). However, measures had not changed much in the 2022 Shanghai lockdown. Another such example lies in China’s persistence to use its domestically developed vaccines despite studies citing its lower effectiveness compared to other vaccines such as Pfizer (Olcott et al.). Such insensitivity demonstrates a lack of commitment to welfare maximisation, which is anti-utilitarian.

Issues with Utilitarianism

Utilitarians seek to maximise welfare. Though we have reinterpreted welfare as QALYs and economic gains/losses so far, under classical utilitarianism welfare means pleasure. Pleasure is subjective: how much pleasure one derives from a certain outcome depends on the individual’s opinion about its desirability.

An issue arises. There are many who are unaffected by the policy. By definition, these individuals do not experience any lockdowns. So far in the analysis I have assumed them to be indifferent. However, it is not inconceivable for them to be extremely pro-lockdown. This could be partially because they are not negatively affected themselves. It could have to do with their risk attitudes: they may be very risk averse. It could also be partially because of how lockdowns and the Zero Covid policy in general have been portrayed as the best policy available, and an absolute zero seen as absolutely necessary. In fact, Nancy Qian, a professor of Managerial Economics and Decision Sciences at Northwestern University cites the unwillingness of parts of the population to diverge from Zero Covid as an obstacle for China to open up.

If a large number of people do derive intense satisfaction from pursuing Zero Covid policy and demand lockdowns which consequently maximize welfare, then utilitarians would demand locking down, regardless of the suffering it may cause[8]. Is this acceptable? Stripping away from the particulars, this is not dissimilar to the problem faced by the ones who walk away from Omelas. Omelas is a fictional city constructed by Ursula Le Guin. Residents of Omelas experience eternal happiness by subjecting a single child to eternal suffering. They are ignorant of the child until they turn adults. When they finally see the child for the first time, they inevitably ask themselves: Can the happiness of the masses justify the suffering of the few? Moreover, can my happiness be built upon others’ suffering?

Utilitarians say yes[9]. But you may want to walk away from Omelas instead.

A Kantian Analysis

Kantian ethics is the system of morality developed by Immanuel Kant. It is deontological, meaning whether an action is right or wrong for a Kantian depends on the action itself instead of its consequences. It is the stark opposite of utilitarianism, which is only concerned with the consequences of actions and is consequentialist. Considering these contrasting theories of ethics gives us a more comprehensive understanding of the matter at hand.

The notion of rights is central to Kantian ethics. For Kant, each person has a set of inviolable rights which everyone (including oneself) has a duty to uphold. These are intrinsic rights which one obtains by nature of being a human. It would be immoral to not perform one’s duty. Kant holds that by having the ability to self-legislate, humans are distinct from animals and objects in general. The ability to self-legislate, otherwise known as autonomy, means that as humans our actions are not determined by the Law of Physics. It is in this way autonomy gives us freedom which for Kant nothing else possesses. Kantian ethics motivates moral actions by resorting to freedom: insofar as one is human, one must strive to self-legislate to maintain freedom, otherwise one ceases to be human. To self-legislate by definition requires one to follow a Law of actions. This Law should be universal in the sense that it should apply to all free beings at all times. Similarly, the Law of Physics is universal in that it applies to all objects at all times. Kant names this Law the Categorical Imperative. The Categorical Imperative establishes actions that one must and must not do, i.e., one’s duties. In being an autonomous free being, humans must follow the Categorical Imperative.

The Categorical Imperative is thus an implication of and a condition for one’s freedom. It is most often expressed in the form of the formula of universal law, which states: “Act only according to that maxim through which you can at the same time will that it become a universal law”. (Kant)

A maxim is a rule that an action can be generalized to. For example, “To borrow money and not return it when I need it” is a maxim. The formula of universal law then asks us to assess whether a state in which everyone behaves this way is practically possible. If it is not, then it is one’s duty not to do so. By applying the formula, we find that it is indeed immoral to borrow money without returning it because if everyone were to do so, then no one would lend money to anyone as they know that they would never get the money back. In this way, the action “to borrow money” would be impossible in the first place because it is impossible to borrow without anyone willing to lend. In applying the formula of universal law and following the Categorical Imperative, one shows full respect for the equality between all free beings.

However, the formula of universal law cannot be used to judge the ethical status of government policies because it is dealing with inner freedom – namely, an individual’s moral status as a free will. Government policies affect citizens’ capacity to act in accordance with their will – what Kant calls external freedom – instead (Kant and Reiss 22). Kant develops the Universal Principle of Rights based on the Categorical Imperative to elucidate the implications of equal moral beings’ claim to external freedom. The Universal Principle of Rights says: “Any action is right if it can coexist with everyone’s [external] freedom in accordance with a universal law” (Kant and Reiss 136). With this, we are able to assess the ethical status of government policies, including the policies adopted as part of China’s Zero Covid policy.

Rawls’ Original Position

The Universal Principle of Rights is rather abstract and hard to apply. How do we know if the actions demanded by a policy are capable of ‘coexisting with everyone’s freedom’? Rawls’s thought experiment of the original position helps us decide (Freeman).

The original position is unlike the pre-social state of nature (Freeman). Instead, it is ‘original’ in the sense that it requires people to temporarily strip away from their particular social characteristics- e.g., one’s gender, class, race, skills and wealth, in order to think first and foremost, as equally free moral beings (Rawls 102). This is in line with Kant’s idea that the most fundamental human characteristic is the ability to behave morally by following the Categorical Imperative. Under such an original position, people together decide the policies they would follow (Rawls 118). This process of co-legislation ensures that procedurally, everyone’s external freedom is equally respected by giving them equal capacity to choose (ibid). This is the formal representation of Kant’s requirement that right actions must ‘coexist with everyone’s freedom’. Meanwhile, the ‘stripping away’ from the particulars which constitutes the famous ‘veil of ignorance’ aims to prevent people from making biased actions in favour of their private interests (ibid). Applying the veil of ignorance also ensures that people’s equal claim to external freedom is substantive. Otherwise, in the process of co-legislation those with certain social characteristics may have greater decision-making power compared to others, inconsistent with the moral equivalence of all beings. Thus, this thought experiment proposed by Rawls helps concretize Kant’s Universal Principle of Rights and is adopted in the evaluation below.

Shanghai’s Lockdown as Seen From the Original Position

To evaluate the ethical status of Shanghai’s lockdown from the Kantian perspective, we ask ourselves: Would I endorse such actions in the original position? If the answer is ‘no’, then the policy is inconsistent with our moral status as equal and free beings, and it is inadequate within the Kantian framework which values equality and freedom above all else.

In practice, the veil of ignorance forces people in the original position to factor in the risk that they themselves may end up in unfavourable situations in the society (outside of the original position) (Freeman). This means that people would endorse actions that take care of people in unfavourable positions (Rawls 53). This solves the moral hazard problem where those acting do not suffer the consequences of their own actions, leading to irresponsible actions. Behind the veil of ignorance, one does not know whether oneself would be the one bearing consequences. Thus, it is wise to endorse actions which could fulfil the policy goal with the least negative consequences to all stakeholders. Many implementation strategies seen in Shanghai’s lockdowns were instances of the moral hazard problem. For example, officers would take residents who reported positive results to quarantine centres after they had already tested negative because the officers themselves needed not to experience the distress. How some residents requiring emergency assistance were refused entry at hospitals due to lack of a valid negative test result is another such example. People in the original position would object to such treatments, rendering these actions unethical.

Yet there is a more fundamental injustice lying behind these moral hazard problems: the policy goal of Zero Covid in itself. The political accountability to ‘those above’ prevalent in China exerts downward pressure on officers to follow orders. This in part gives rise to many of the moral hazard problems observed by providing those acting (the officers) with an incentive to disregard the consequences borne by ordinary residents. It does so by attaching potentially high costs to divergence from order. Consider the second example just quoted. If an officer lets the emergency patient into the hospital without a valid test and the patient later tests positive, the officer risks fines and may even lose their job. The fact the officer strayed from order with the best intentions may play little role in alleviating the punishment, because the only thing that matters to their superior is the act of allowing someone into the hospital has led to an instance of failure to attain Zero Covid. To avoid this high cost, officers may rationally choose to follow orders regardless of the residents’ experience. People in the original position would take issue with this as no one knows whether they may end up in the same precarious position as the unfortunate officer. The institution may not be open to change in the short to medium term, but the policy goal itself could have been different. People in the original position would likely endorse a policy goal that at least places a lesser emphasis on achieving the number ‘Zero’ but with a greater emphasis on ensuring people’s adequate access to basic goods such as health and essential rights instead.

This brings us to the final question of whether people in the original position would endorse the lockdown. There seems to be more uncertainty around this. On the one hand, not knowing their own susceptibility to death from Omicron, co-legislators may be inclined to endorse lockdowns to minimize the risk of dying. On the other hand, in the face of Omicron’s relatively low death rate and the heavy economic burdens and turmoil individuals in lockdowns face, without the knowledge of whether they may be subject to lockdowns, a more likely event than getting fatally ill due to Covid, people in the original position may endorse coexistence instead. What is more certain is that if lockdowns were chosen, people in the original position would advocate mitigating the negative effects imposed upon those in lockdowns by adopting more moderate NPIs. Likewise, if they chose to coexist with Omicron, they would minimize the number of deaths with vaccination campaigns and less intrusive measures such as wearing masks and hand washing.

Conclusion

By considering two ethical theories founded upon completely different principles, i.e., utilitarianism and Kantian ethics, I argue that from both perspectives, the Zero Covid Policy and its implementation seen in China are ethically flawed. From the utilitarian point of view, it does not maximize welfare, and incorporates aspects unconducive to the goal of welfare maximization. From the Kantian point of view, the policy diverges from the choices of free and equal agents in the original position, indicating a lack respect for the equal freedom of all. This article also highlights the issue of moral hazard as one of the causes of the implementation failures seen in Shanghai’s lockdown. As the fight against Covid goes on in China, this article calls for a more scientific and flexible policy-making process with regard to the pandemic response, a more serious attempt to cater policy goals to the particular policy environment of the country, and a greater consideration for all citizens across all aspects.

Bibliography

Alim, Arjun Neil, et al. ‘China Digs in for Permanent Zero-Covid with Testing and Quarantine Regime’. Financial Times, 9 June 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/d3f3b52c-e4bb-40c2-b2e9-afc2b22f0c19?accessToken=zwAAAYHfhO7_kdPT87Us5LtAwtOy6a_Csi8MGQ.MEUCIHoIkT94IfF7pdVBKr8MNDYB8cLPnO9fkVHEebzEBKtDAiEAwm1bLtI70kJxsBvGeiquCndEFCRLO2ALkqB9oVK2dAw&sharetype=gift?token=856ed5dc-9632-4825-99f0-4f4ddb7c8b9e.

Allen, Douglas W. ‘Covid-19 Lockdown Cost/Benefits: A Critical Assessment of the Literature’. International Journal of the Economics of Business, vol. 29, no. 1, Jan. 2022, pp. 1–32. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1080/13571516.2021.1976051.

Annemans, Lieven. ‘Do You Know What a QALY Is, and How to Calculate It?’ CELforPharma,https://www.celforpharma.com/insight/do-you-know-what-qaly-and-how-calculate-it. Accessed 6 July 2022.

Banks, Christina, et al. ‘Cost of Vaccine Delivery Strategies in Low- and Middle-Income Countries during the COVID-19 Pandemic’. Vaccine, vol. 39, no. 35, Aug. 2021, pp. 5046–54. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.06.076.

Bhandari, Bibek, et al. ‘Memory Project: The Shanghai Lockdown’. Sixth Tone, https://interaction.sixthtone.com/feature/2022/Memory-Project-The-Shanghai-Lockdown/. Accessed 6 July 2022.

Bloomberg. China to Lock down 8 Districts, Test Millions as Covid Cases Rise Again | Business Standard News. 10 June 2022, https://www.business-standard.com/article/international/china-covid-19-cases-8-districts-to-lockdown-test-millions-as-covid-cases-rise-again-122061000153_1.html.

Brant, Robin. ‘Shanghai Moves to Impose Tightest Restrictions Yet’. BBC News, 11 May 2022. www.bbc.co.uk, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-61404082.

Brink, David. ‘Mill’s Moral and Political Philosophy’. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta, Spring 2022, Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, 2022. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2022/entries/mill-moral-political/.

Burki, Talha. ‘Dynamic Zero COVID Policy in the Fight against COVID’. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, vol. 10, no. 6, June 2022, pp. e58–59. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00142-4.

Cai, Jun, et al. ‘Modeling Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron in China’. Nature Medicine, May 2022. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01855-7.

Chen, Jingjing, et al. The Economic Cost of Locking down like China: Apr. 2022, p. 43.

Chen, Yawen. ‘Breakingviews – This Chinese Jobs Crisis Could Be Its Worst’. Reuters, 20 June 2022. www.reuters.com, https://www.reuters.com/breakingviews/this-chinese-jobs-crisis-could-be-its-worst-2022-06-20/.

China Brief: Shanghai Enters Full COVID-19 Lockdown. https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/03/30/china-shanghai-covid-lockdown/. Accessed 8 July 2022.

CodeBlue. ‘Sinovac Retail Price Cap RM77 Per Dose, Excluding Other Charges’. CodeBlue, 13 Jan. 2022, https://codeblue.galencentre.org/2022/01/13/sinovac-retail-price-cap-rm77-per-dose-excluding-other-charges/.

‘Covid-19: Estimates for China’. Epiforecasts, 27 Apr. 2022, https://epiforecasts.io/covid/posts/national/china/.

‘Covid-19: Estimates for Singapore’. Epiforecasts, 27 Apr. 2022, https://epiforecasts.io/covid/posts/national/singapore/.

Covid-19 Lockdown Cost/Benefits: A Critical Assessment of the Literature. https://www-tandfonline-com.gate3.library.lse.ac.uk/doi/epub/10.1080/13571516.2021.1976051?needAccess=true. Accessed 6 July 2022.

CSSEGIS and Data. COVID-19 Data Repository by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University. 2020. GitHub, https://github.com/CSSEGISandData/COVID-19. Accessed 27 June 2022.

Davidson, Helen. ‘Shanghai Reportedly Bans Media Use of the Term “Lockdown” as Lockdown Ends’. The Guardian, 2 June 2022. The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/jun/02/shanghai-reportedly-bans-media-use-lockdown-china.

Freeman, Samuel. ‘Original Position’. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 3 Apr. 2019, https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2019/entries/original-position/.

GT Staff Reporters. GT on the Spot: Shanghai Residents Embrace and Celebrate New Start at Midnight of June 1 – Global Times. 1 June 2022, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202206/1267114.shtml.

Guardian News. Shanghai Residents Bang Pots and Pans in Covid Lockdown Protest. 2022. YouTube,https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p5J1jYxYPJY.

Himmler, Sebastian. ‘Estimating a Monetary Value of Health: Why and How? | News | CORDIS | European Commission’. CORDIS EU Research Results, 18 Nov. 2019, https://cordis.europa.eu/article/id/411538-estimating-a-monetary-value-of-health-why-and-how.

Huld, Arendse, and Qian Zhou. ‘What Are the 50 New Support Measures to Restart Shanghai’s Economy?’ China Briefing, 13 June 2022, https://www.china-briefing.com/news/shanghai-releases-50-new-support-measures-to-restart-economy-may-29-2022/.

Kant, Immanuel. Immanuel Kant – On Moral Principles. Thompson Rivers University/BCcampus, 1785, https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/classicreadings/chapter/immanuel-kant-on-moral-principles/.

kant, Immanuel. Political Writings. Edited by Hans Siegbert Reiss, Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Kocot, Ewa, et al. ‘The Application of the QALY Measure in the Assessment of the Effects of Health Interventions on an Older Population: A Systematic Scoping Review’. Archives of Public Health, vol. 79, no. 1, Nov. 2021, p. 201. BioMed Central,https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-021-00729-7.

Koetse, Manya. ‘Infants with COVID-19 Separated from Parents: Shanghai “Baby Quaratine Site” Sparks Online Anger’. Whatsonweibo.Com, 2 Apr. 2022, https://www.whatsonweibo.com/infants-with-covid-19-separated-from-parents-shanghai-baby-quarantine-site-sparks-online-anger/.

Kwan, Rhoda. ‘How Hong Kong’s Vaccination Missteps Led to the World’s Highest Covid-19 Death Rate’. BMJ, vol. 377, May 2022, p. o1127. www.bmj.com, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.o1127.

LE GUIN, URSULA K. ‘The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas (Variations on a Theme by William James)’. Utopian Studies, vol. 2, no. 1/2, 1991, pp. 1–5.

Liu, Jue, et al. ‘The Dynamic COVID-Zero Strategy in China’. China CDC Weekly, vol. 4, no. 4, Jan. 2022, pp. 74–75. weekly.chinacdc.cn, https://doi.org/10.46234/ccdcw2022.015.

Luo, Yahan, and Peiyue Wu. ‘What Does It Cost to Test China for COVID-19?’ SixthTone, 9 June 2022, https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1010523/https%3A%2F%2Fwww.sixthtone.com%2Fnews%2F1010523%2Fwhat-does-it-cost-to-test-china-for-covid-19%253F.

Ma, Xin, et al. ‘Dynamic Disease Manifestations Among Non-Severe COVID-19 Patients Without Unstable Medical Conditions: A Follow-Up Study — Shanghai Municipality, China, March 22–May 03, 2022’. China CDC Weekly, p. 7. Zotero, https://doi.org/10.46234/ccdcw2022.115.

‘MOH | Past Updates on COVID-19 Local Situation’. Ministry of Health of Singapore, https://www.moh.gov.sg/covid-19/past-updates. Accessed 6 July 2022.

Normile, Dennis. ‘An Undebatable Political Decision’: Why China Refuses to End Its Harsh Lockdowns. https://www.science.org/content/article/undebatable-political-decision-why-china-refuses-end-its-harsh-lockdowns. Accessed 6 July 2022.

Olcott, Eleanor, et al. ‘China’s Patchy Vaccine Campaign Leaves Elderly at Risk’. Financial Times, 29 Mar. 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/a0dd80f7-3dda-4ea2-bfc2-480c5f10ef06.

Palmer, James. China Brief: Shanghai Enters Full COVID-19 Lockdown. 30 Mar. 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/03/30/china-shanghai-covid-lockdown/.

People’s Republic of China – Place Explorer – Data Commons. https://datacommons.org/place/country/CHN?utm_medium=explore&mprop=lifeExpectancy&popt=Person&hl=en. Accessed 6 July 2022.

Peter, Fabienne. Political Legitimacy. Edited by Edward N. Zalta, Apr. 2010. plato.stanford.edu,https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2017/entries/legitimacy/.

Qian, Nancy. ‘What Is China’s COVID Endgame? | by Nancy Qian’. Project Syndicate, 13 Apr. 2022, https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/china-unsustainable-zero-covid-policy-by-nancy-qian-1-2022-04.

Rawls, John. A Theory of Justice. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1999.

Ren, Daniel, and Shidong Zhang. ‘Shanghai Offers US$22 Billion Aid for Businesses to Survive Lockdown’. South China Morning Post, 29 Mar. 2022, https://www.scmp.com/business/banking-finance/article/3172250/shanghai-offers-140-billion-yuan-lifeline-tax-rebates-rent.

Ritchie, Hannah, et al. ‘Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19)’. Our World in Data, Mar. 2020. ourworldindata.org, https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations.

Roelfs, David J., et al. ‘Misery Loves Company? A Meta-Regression Examining Aggregate Unemployment Rates and the Unemployment-Mortality Association’. Annals of Epidemiology, vol. 25, no. 5, May 2015, pp. 312–22. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.02.005.

Savulescu, Julian, et al. ‘Utilitarianism and the Pandemic’. Bioethics, vol. 34, no. 6, May 2020, pp. 620–32. Wiley Online Library, https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12771.

‘Shanghai: Govt Finance: Source of Fund: Budgetary Local Debt | Economic Indicators | CEIC’. Ceicdata.Com,https://www.ceicdata.com/en/china/local-government-shanghai/shanghai-government-finance-source-of-fund-budgetary-local-debt. Accessed 6 July 2022.

‘Shanghai Lockdown Delivers $28 Billion Hit to Global Trade’. Russsell.Co.Uk, 5 May 2022, https://www.russell.co.uk/ProductStories/2757/shanghai-lockdown-delivers-28-billion-hit-to-global-trade.

Shanghai Municipal Health Commission. 4月27日市、区主要医疗机构暂停医疗服务情况__上海市卫生健康委员会. 27 Apr. 2022, https://wsjkw.sh.gov.cn/xwfb/20220427/791363aadc084af4a87fe95509e0e044.html.

Smart, J. J. C., and Bernard Williams. Utilitarianism: For and Against. Cambridge University Press, 1973.

‘The Way Chinese Think about Covid-19 Is Changing’. The Economist, 16 Apr. 2022. The Economist, https://www.economist.com/china/2022/04/16/the-way-chinese-think-about-covid-19-is-changing.

‘Updates to Health Protocols’. Singapore Government Agency, 22 Apr. 2022, http://www.gov.sg/article/updates-to-health-protocols.

‘Voices of April’ Shanghai, 4/2022 with English Subtitles《四月之声》上海,2022年4月. 2022. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8mFmfCyIB3c.

‘Who Is at High Risk from Coronavirus (COVID-19)’. Nhs.Uk, 1 Mar. 2021, https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/coronavirus-covid-19/people-at-higher-risk/who-is-at-high-risk-from-coronavirus/.

Xinhua. ‘China’s Surveyed Urban Unemployment Rate at 5.5% in Q1’. The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, 18 Apr. 2022, https://english.www.gov.cn/archive/statistics/202204/18/content_WS625cfaadc6d02e533532983f.html.

—. ‘Shanghai’s Temporary Hospitals Expected to Accommodate over 70,000 Patients’. The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, 5 Apr. 2022, https://english.www.gov.cn/news/topnews/202204/05/content_WS624c374dc6d02e5335328cab.html.

Yeung, Jessie. Shanghai Covid-19: Video Shows Health Worker Beating Dog to Death after Owner Tests Positive – CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2022/04/08/china/shanghai-corgi-death-china-covid-intl-hnk/index.html. Accessed 6 July 2022.

Yip, Waiyee. ‘Shanghai Installs Metal Barriers and Fences around People’s Homes to Stop Them from Going out, in Its Latest Brutal Measure to Battle Covid’. Insider, https://www.insider.com/shanghai-lockdown-metal-barriers-and-fences-seal-off-peoples-homes-2022-4. Accessed 6 July 2022.

Yu, Sun. ‘China Offers Covid Vaccine Insurance to Win over Jab Sceptics’. Financial Times, 7 June 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/a191cbdf-218c-4968-a494-36082e350018.

Yu, Sun, and Yuan Yang. ‘Why China’s Economic Recovery from Coronavirus Is Widening the Wealth Gap | Free to Read’. Financial Times, 18 Aug. 2020, https://www.ft.com/content/e0e2940a-17cb-40ed-8d27-3722c9349a5d.

Zhang, Phoebe, and Alice Yan. Shanghai Enters Second Phase of Lockdown in West of City – but Covid-19 Restrictions Remain in Other Parts | South China Morning Post. 1 Apr. 2022, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/3172721/shanghai-enters-second-phase-lockdown-west-city-covid.

Zhang, Xin, et al. ‘Monitoring SARS-CoV-2 in Air and on Surfaces and Estimating Infection Risk in Buildings and Buses on a University Campus’. Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology, Apr. 2022. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-022-00442-9.

Zhuang, Pinghui. Shanghai Rules out Citywide Covid-19 Lockdown to Protect China’s Economy | South China Morning Post. 26 Mar. 2022, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/science/article/3171977/shanghai-rules-out-citywide-covid-19-lockdown-protect-chinas.

‘上海疫情逝者名单(不完全统计210+位)’. Airtable, https://airtable.com/shrQw3CYR9N14a4iw/tblTv0f9KVySJACSN. Accessed 6 July 2022.

夏松. ‘“大白”入室消杀 上海青年回呛 爆红网络 – 大纪元’. 大纪元 www.epochtimes.com, 13 May 2022, https://www.epochtimes.com/gb/22/5/12/n13734703.htm.

東森新聞 CH51. 上海方艙「漏水如雨下」 民眾嘆:屋頂都塌了. 2022. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GifLoHNWb0g.

薛佩菱. ‘【新冠肺炎】封城两个多月后解封 上海市发“致全市人民的感谢信” | 国际’. 東方網 馬來西亞東方日報, 1 June 2022, https://orientaldaily.org/news/international/2022/06/01/490070.

Endnotes

[1] For more on individuals’ experiences during the Shanghai lockdown, see https://interaction.sixthtone.com/feature/2022/Memory-Project-The-Shanghai-Lockdown/ .

[2] Economic disruption mitigated is disregarded because evidence from countries such as the UK show that coexisting with the virus has a limited negative effect on the economy. Without a lockdown, China’s healthcare system would also be under strain. However, when estimating number of deaths, Covid deaths due to limited health system capacity are also included.

[3] The accuracy of such estimations has been called into question, e.g. Allen 2022. However, due to the lack of reliable alternatives it is nonetheless adopted for the purpose of this article.

[4] Calculated by number of deaths / total population in China.

[5] 2019 GDP figure.

[6]This article was first made available online on China’s CDC Weekly on 18th June, 2022. On 24th June, 2022, I discovered that the article has been pulled down from https://weekly.chinacdc.cn/index.htm.

[7] Figure from unofficial records collated by Shanghai’s residents. See https://airtable.com/shrQw3CYR9N14a4iw/tblTv0f9KVySJACSN (in Chinese).

[8] Insofar as the level of suffering does not change the fact that lockdowns are welfare-maximizing.

[9] Insofar as welfare maximization is satisfied.