Council for Inclusive Capitalism: Greenwashing Dangers

By Cassie Ransom

The Council for Inclusive Capitalism (CIC) seeks to reform the current financial system to foster a more just and inclusive model of capitalism. Given existing systemic issues with greenwashing in companies’ Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance (ESG) reports, the CIC is at risk of being used as a platform for greenwashing. Accepting members as stewards of inclusive capitalism whose overall ESG practices contradict the Council’s values is likely to further erode social capital, the opposite of the Council’s goal. Since greenwashing impedes accountability for real change, it undermines the Council’s vision of equality of opportunity, equity of outcomes and intergenerational equity, and it violates the Council’s values of trust, sustainability, responsibility and fairness. Greenwashing thus incurs a significant detriment to the common good. The success or failure of the CIC’s mission to maximise the common good resides in the systems it puts into place to ensure members are truly committed to inclusive capitalism. Recommendations are provided to guide the Council in this process.

The Council for Inclusive Capitalism

Inclusive capitalism is a movement to reform our current financial system to address its inequities. According to the newly formed Council for Inclusive Capitalism (CIC), this modified capitalism is ‘fundamentally about creating long-term value for all stakeholders – businesses, investors, employees, customers, governments and communities’. Among other things, inclusive capitalism aims to ensure a just distribution of opportunities and outcomes, a financial system which is fairer to those prevented from full participation, and intergenerational equity.

The Council for Inclusive Capitalism with the Vatican marks an alliance between Pope Francis and a group of influential financiers and global leaders called the Guardians. The Council describe its efforts as providing ‘a moral and market imperative to make economies more inclusive and sustainable with a movement of bold, business led actions which span the economic system’.

The Guardians meet annually with Pope Francis for moral guidance on how to reform the private sector to reflect a more just and inclusive model of capitalism. The Pontiff has publicly endorsed a financial system which ‘leaves no one behind, that discards none of our brothers or sisters’ (Francis, 2020).

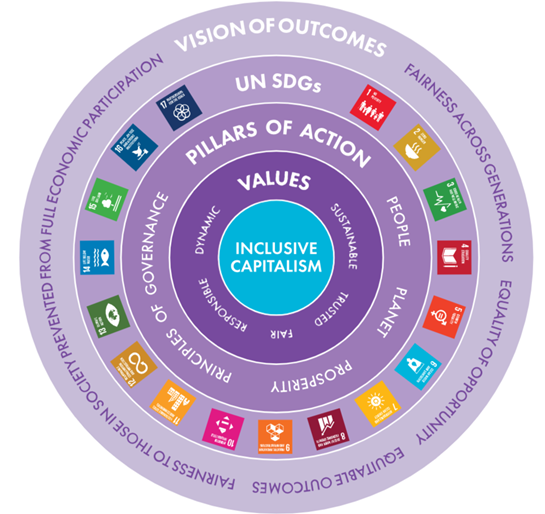

In practice, organisations will work to realise these values by making actionable commitments aligned with the World Economic Forum International Business Council’s Pillars for sustainable value creation—People, Planet, Principles of Governance, and Prosperity- which promote the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The Council collectively represents over $10.5 trillion worth of assets under management, $2.1 trillion in market capitalisation and 200 million workers over 163 countries and territories. Among the members are BP, Allianz, Bank of America, Estee Lauder, Mastercard, Visa and Johnson and Johnson. As of February 2021, the Council boasts 278 commitments from 44 organisations.

The Ideological Debate: Stakeholder vs. Shareholder Capitalism

The CIC’s reforms are necessarily driven by a critique of capitalism as it stands. The Council itself offers the appraisal in only a rather limited and superficial way, stating ‘capitalism lifts people out of poverty and powers global innovation and growth. But to address the challenges of the 21st century, capitalism needs to adapt’.

More comprehensive critiques of pure free market capitalism have been expounded by Council members such as UN special envoy Mark Carney, founder Lynn Forester de Rothschild and Pope Francis.Carney attacked market fundamentalism, or the belief in the power of the market to solve most social and economic issues, in his 2014 speech as the Governor of the Bank of England. He argued: ‘Capitalism loses its sense of moderation when the belief in the power of the market enters the realm of faith. In the decades prior to the [Global Financial Crisis], such radicalism came to dominate economic ideas and became a pattern of social behaviour’. Likewise, the Pontiff challenged the sanctity of pure free market capitalism when he argued in Fratelli Tutti the need for civil institutions which ‘look beyond the free and efficient working of certain economic, political or ideological systems, and are primarily concerned with individuals and the common good’. Finally, Rothschild challenged the view in Modern Finance Theory (MFT) that ethics and finance are fundamentally separate when advocating for the notion that reforming capitalism requires moral guidance. In an interview with Reuters, she argued ‘there are many efforts to make capitalism inclusive and sustainable, but what we have been missing is a moral base for the movement – the poetry to the prose of our action’ (Balch 2020).

The Council’s arguments fit broadly into the debate between shareholder and stakeholder capitalism. The movement the Council seeks to advance is a variant of stakeholder capitalism, a theory authored in 1984 by Edward Freeman. Stakeholder capitalism proposes businesses and firms should consider their impacts on all stakeholders. Stakeholders include employees, consumers, investors and members of the public whose interests may be damaged by negative externalities. For example, corporations with large carbon footprints have a duty under stakeholder capitalism to consider the effects of their GHG emissions on future generations.

Conversely, shareholder capitalism holds the sole responsibility of businesses and firms is to maximise profits for their shareholders (MSV), not to consider the interests of wider stakeholders. Shareholder capitalism shares the view propounded by Milton Friedman that businesses’ sole social responsibility is to their shareholders. Friedman argues when businesses reduce shareholder payouts and invest profits into social initiatives instead, they are effectively ‘spending somebody else’s money’ (Detrixhe, 2020). He goes so far as to claim company executives with a social conscience “are unwitting puppets of the intellectual forces that have been undermining the basis of a free society” (1970).

Friedman’s views were instrumental in the development of Modern Finance Theory (MFT), which has dominated the financial sphere since the 1970s (Perez et al., 2010). Foremost among the assumptions of MFT is the view that human beings are self-interested rational agents who seek to maximise profit. Friedman authored the separation thesis, saying economics can be viewed as a positive science and thus separate from ethical concerns, which are primarily evaluative (Joakim 2008). The latter views have calcified into an unquestionable ideology over time, and for the past several decades have served as the central tenets of finance. However, MFT has been subject to increasing scrutiny in recent years. The Seven Pillars Institute critiqued MFT and free market capitalism in early 2010, and the views expressed by Carney, Rothschild and Pope Francis all target MFT in some form.

The financial crisis is often cited as highlighting issues with MFT and the maximisation of shareholder profit to the exclusion of other values. The crisis shone a light on rising inequalities and drew attention to the injustices of the market. Forester’s own transition to Inclusive Capitalism followed the 2008 global financial crisis (GFC), prior to which she claimed “Basically, I was a money-is-good, neo-liberal person who believed in the sanctity and sanity of free markets. A rising tide lifts all boats, and all that,” (Balch 2020). Carney (2014) argues the identification of bubbles, banks that were ‘too big to fail’ and equity markets that favoured ‘technologically empowered’ investors over retail investors eroded public trust. The resulting losses in social capital, or the networks and relationships among market participants which operate on the basis of shared values and beliefs, threatens the long-term trajectory of the market. Inclusive capitalism is thus part of a broader movement to reconsider the primacy of MSV in the wake of the GFC, seeking to promote outcomes of equality, justice, and the interests of all stakeholders.

The Council for Inclusive Capitalism’s Vision and Values: An Ethics Analysis

The Council justifies its vision of equality of opportunity, fairness, intergenerational equity and equity of outcomes with a consequentialist argument. The CIC asserts the current financial system ‘has lifted billions of people out of poverty, but many in society have been left behind and the planet has paid a price’. Likewise, Carney (2014) argues that over the past few decades, economic inequality has risen whilst social mobility and equality of opportunity have fallen, creating an unjust distribution of goods and resources and challenging long-term economic stability. Inclusive capitalism in its operational form, by contrast, is purported to foster equality of opportunity, equitable outcomes and fairness across generations. The Council argues ‘there is growing evidence that equality of opportunity is good for economic growth, that feeling a sense of that inclusion and fairness contributes much to happiness and well-being’. Inclusive Capitalism thus effectuates more socially desirable consequences, guided by the Council’s values of trust, fairness, responsibility, dynamism and sustainability as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Infographic of the CIC’s values, the WEF/IBC’s pillars for sustainable value creation, the SDGs and the Council’s vision. From CIC’s ‘About Us’ section on their website.

While the Council’s ethics are undoubtedly influenced by Pope Francis’ guidance, it aims to be non-sectarian. In an interview with Quartz magazine, Lynn Forester de Rothschild said of the Council’s work “this is of course informed by the [Christian] gospel, but it speaks about what Aristotle was speaking about 300 years before Christ about humanity’s need to be responsible for each other” (Quito, 2020). The Aristotelian concept of ‘common interests’ denotes, among other things, that communities are ‘bound together in a social relationship marked by a certain form of mutual concern: members care that they and their fellow members live well’ (Hussain, 2018). The secular Artistotelian concept of ‘common interests’ bears similarity to the Catholic notion of the common good, which is clearly evident in the Council’s vision.

The Catholic Catechism defines the common good as ‘the sum total of social conditions which allow people, either as groups or as individuals, to reach their fulfillment more fully and more easily’. In short, according to the common good, all people ought to have access to goods and resources necessary to attain healthy and fulfilling lives. The primacy of the common good is frequently reinforced by Pope Francis, who made over thirty references to it in his October 2020 Fratelli Tutti. The Pontiff even stressed the ethical imperative to foster the common good in his formal address to the Council, stating; ‘Your efforts remind us that those who engage in business and economic life are in fact possessed, as bears repeating, of a noble vocation, one that serves the common good by striving to increase the goods of this world and make them more accessible to all’ (Francis, 2020). While the Council does not explicitly reference Catholic social teaching, the notion of creating social conditions which enable people to thrive is clearly evident in the Council’s vision of equality of opportunity, equity of outcomes and intergenerational equity.

Employing the notion of the common good, the Council’s ethics can be viewed as a utilitarian form of consequentialism. Broadly summarised, classical utilitarians conceive of maximising the good as realising ‘the greatest amount of good for the greatest number’, where ‘the good’ constitutes happiness or well-being (Drew, 2017). The Catholic notion of the ‘common good’ is different in a few key ways: ‘the good’ is defined in terms of the provision of the appropriate conditions which enable one’s capabilities to prosper, as opposed to straightforwardly in terms of actual happiness or well-being. The moral imperative to reform the capitalist system in a way that fosters the common good is nonetheless a utilitarian ideal. The utilitarian calculation of benefits and costs demonstrates a system which is ‘inclusive’, which affords equality of opportunity to all, trumps a system which benefits only an elite minority. Inclusive capitalism is predicted to produce a greater amount of good for a greater number than shareholder capitalism. The ethical concept of the common good will thus be invoked throughout the present paper to evaluate the Council’s work, particularly its vulnerability to greenwashing.

Notably, the idea that most people favour a social distribution which is approximately equitable over one which favours an elite minority does not require a utilitarian ethical justification. Carney, in his 2014 speech, offered a more secular ethical argument for Inclusive Capitalism. He contends that societies value intergenerational equity, equality of opportunity and equity of outcomes because 1) these factors drive economic growth, and most people disvalue a social order which disproportionately benefits an privileged subgroup; 2) inequality reduces well-being by reducing peoples’ sense of community and 3) an equal social distribution ‘appeals to a fundamental sense of justice’, words directly replicated on the CIC website, along with the trinity of outcomes stated above. Carney argues that these three values (equality of opportunity, intergenerational equity and equity of outcomes) comprise a Rawlsian social contract which is in the interests of most people because, ‘Who behind a Rawlsian veil of ignorance – not knowing their future talents and circumstances – wouldn’t want to maximise the welfare of the least well off?’

The Commitments

Organisations working with the CIC make public commitments to contribute to the advancement of inclusive capitalism. Such commitments consist of internal company changes, such as Allianz’s commitment to phase out coal-based business models from its portfolios by 2040, or external grants for issues of social importance, such as fostering environmental sustainability. The organisations are required to provide a summary, objective, metrics and targets and affiliated SDGs for each commitment they make.

So far, there is limited information available on how the Council plans to hold organisations accountable to their commitments. Since they are not legally binding, the companies face no penalties for eschewing their commitments besides ‘the risk of disappointing the pope’, as one New York Times article notes (Sorkin et al., 2020). Although disclosure is clearly expounded as one of the CIC’s central values it is unclear whether Council members are obligated to report their progress, and if so, to what standard. In an article for Quartz magazine, Anne Quito (2020) obtained a statement claiming that organisations’ commitments would be ‘audited annually via a scorecard system’. There is so far no information available to corroborate this claim on the CIC website, but the Council’s Director of Communications Amanda Byrd wrote via personal communication that ‘This is a priority for us, and the Council is working to solidify our annual evaluation process in the coming months’.

Greenwashing and ESG Reporting

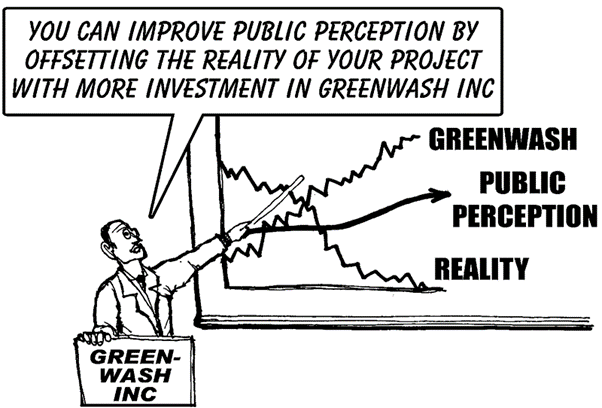

Since membership on the Council provides organisations with an opportunity to tout their progress on Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance (ESG), it may facilitate greenwashing or ‘faux-ESG’ (Cherry & Snierson, 2010). Greenwashing or ‘faux ESG’ occurs when firms only engage superficially with ESG in ways that are beneficial to their brand while engaging in or failing to modify practices which are environmentally or socially detrimental.

The threat that greenwashing poses to the integrity of the CIC’s work can be delineated into two forms. First, as noted above, the processes for auditing and evaluating organisations’ progress toward their commitments is important in preventing greenwashing. Second, because greenwashing is already a significant problem in sustainability reporting, the Council may be unable to identify when stewards are greenwashing due to a dearth of reliable information on companies’ environmental and social impacts. Eighty-five percent of S&P companies now release sustainability reports (Gaetano, 2019). Such reports are frequently appropriated as a public relations tool rather than for their intended purpose of informing stakeholders about ESG developments. For example, Bhatia (2012) concluded that British Petroleum (BP), a steward on the Council, used ESG reporting following its 2010 Deepwater Horizon spill as a method of diminishing public criticism.

The Council acknowledges that the disclosure and auditing practices organisations use in their independently produced ESG reports will be a key determinant in the transition to inclusive capitalism. In a statement released on January 27th, 2020, the Council commented: ‘to display our progress in contributing to an inclusive capitalism, we recognize that companies and organizations need to measure the positive impact that they are having on their stakeholders. Additionally, measurement and disclosure that is comparable, consistent and material accelerates the sustainable investment necessary to drive needed structural changes’.

The Council encourages the convergence of multiple ESG reporting frameworks toward the development of a universal global standard. The Council also encourage organisations ‘to disclose [their] ESG metrics in line with currently accepted approaches such as WEF/IBC, TCFD, SASB and GRI. However, there are a number of issues with current reporting standards. Without effective mechanisms to ensure that Council members’ statements and metrics are accurate and complete, the Council’s guiding value of ‘trust’ will provide only a vague ethical imperative which lacks safeguards against several serious issues with ESG reporting.

For example, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), one of the frameworks recommended by the CIC, is an international independent standards organisation which seeks to educate companies on disclosure practices relating to sustainability concerns. GRI is the most widely applied framework globally, and is already used by a number of the Council’s stewards. However, several studies argue the GRI is insufficient to prevent greenwashing (Laufer, 2003). Some of the issues with frameworks like the GRI are:

- Ambiguity and Selectivity: organisations may use misleading illustrative examples, omit relevant issues from their materiality analyses and foreground projects with a positive environmental or social impact. For example, a chemical company might highlight its donations to a water charity, but neglect to mention the environmental degradation caused by a chemical effluent it produces. A recent study by the Oxford Brookes Institute found that 72% of the Financial Times Stock Exchange 100 Index used very narrow reporting boundaries in their sustainability assessments (Miles and Ringham 2019), many of whom used the GRI framework.

- Sustainability accounting lacks the infrastructure of finance reporting; finance reports have firm and unambiguous frameworks and standards, are externally audited and legally obligated. Sustainability reports like the GRI lack the equivalent weight and rigour because their standards are not legally enforceable and external audits are voluntary.

Additionally, Companies with worse environmental records may be more motivated to highlight their positive contributions. Charles Cho from the Schulich School of Business has authored multiple scientific papers to this effect, including a 2012 paper in which he found that ‘based on a cross-sectional sample of 92 U.S. firms from environmentally sensitive industries, environmental performance is negatively related to both reputation scores and membership in the Dow Jones Sustainability Index’ (Gaetano 2019). He reasons that ‘if poor environmental performance induces companies to increase their environmental disclosure, and if the disclosure moderates the image of that performance, then poor performance may not result in negative impacts on reputation—and this is obviously not good for the environment,” (Gaetano 2019).

It is also worth noting ESG reports may be misleading without qualifying as greenwashing. Greenwashing requires that discrepancies between actual impact and reported impacts be deliberate, often for the purpose of increasing profit. As co-founder of GRI Alan White notes, sometimes these discrepancies arise due to a failure to accurately predict or measure outcomes, a mistaken application of frameworks, or even internal flaws in those frameworks (Gaetano 2019).

The issues outlined above hinder the Council’s ability to identify members using CIC credentials to disingenuously present themselves as environmentally and socially progressive. If the Council is affiliated with organisations whose net impacts are actually socially and environmentally detrimental, social capital with key stakeholders, such as environmental agencies, is likely to be eroded.

Further, greenwashing effectively enables companies to continue to profit from activities which produce negative social externalities, such as pollution, without public awareness. Since inclusive capitalism aims to ensure the interests of all stakeholders are considered, the socialisation of costs and the privatisation of profit obstructs the mission. In this sense, greenwashing undermines the common good and has the potential to subvert the Council’s core values of trust, responsibility, fairness and sustainability. Greenwashing also impairs the Council’s ability to quantify its own impact by making it difficult to differentiate real reforms from faux-ESG. In fact, the Council may add to existing greenwashing with its commitments system, which magnifies the selectivity issues in ESG reporting by exclusively highlighting companies’ positive contributions. Several of the Council’s stewards promote their socially and environmentally advantageous goals whilst simultaneously eschewing obligations to pay for the externalities of their prior actions. Two case studies illustrate the greenwashing problem.

Greenwashing Case Study I: DuPont

First Sell Toxic Chemical PFAS

DuPont’s commitments to the CIC shows organisations selectively highlight their positive social and environmental contributions while omitting their negative externalities. Since 1998, the company has been facing lawsuits over the environmental and health impacts of the chemical PFAS used in the production of Teflon. A study by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency found PFAS associated with several serious health conditions, including foetal malformation, kidney and testicular cancer and high cholesterol (Martyn et al. 2018). Internal records indicate the company had known about the health risks of PFAS since the 1960s. Among DuPont’s legal challenges was a federal class action lawsuit filed by attorney Robert Billot for the contamination of drinking water in West Virginia and Ohio, which DuPont settled in 2004 (Gillam, 2019). Since then, it has faced numerous individual personal-injury lawsuits. Litigation is currently ongoing.

In 2015 Dupont commenced the process of restructuring itself, consequently transferring its obligations onto entities without the power to pay for ongoing PFAS settlements (Morgenson 2020). Dupont formed a new spin-off company for its former chemical business, Chemours, in 2015 and a second, Corteva Inc. in 2019. A final transaction saw the creation of the ‘new DuPont’ which specialises in electronics, transportation and construction (Morgenson, 2020). The latter company joined the Council in 2020 as a steward of inclusive capitalism. The new company is two steps removed from the legal obligations for PFAS, while Chemours, which has ‘primary responsibility for the estimated tens of billions of dollars in PFAS obligations’ does not have the funds or assets to pay (Morgenson, 2020).

Although DuPont denies the allegations, many claim the restructure was a deliberate attempt to avoid making further settlements: Williams-Derry of the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis stated: “Spinning off your legacy liabilities into a separate corporation and to some other responsible party appears to be part of the standard playbook in these industries’ (Morgenson, 2020). Chemours attempted to sue DuPont in 2019 on the basis that DuPont had concealed the extent of the liabilities it would face for PFAS (Randall, 2020). Environmental protection groups, such as the Sierra Club, voice concern that if Chemours is not solvent, the cost of clean-up will be transferred to taxpayers (Morgenson, 2020).

Then Profit from Cleaning up PFAS

DuPont also specialises in water purification, and in 2019 purchased the company Desalitech Ltd, which uses reverse osmosis to clean chemicals such as PFAS and PFOS out of municipal water utilities (Formuzis 2019). As noted by the Environmental Working Group, this move may enable DuPont to profit from the clean-up of pollution it was responsible for (Formuzis 2019). The damage to DuPont’s legitimacy and social capital resulting from the PFAS scandal is apparent in quotes such as the following from Ken Cook, President of the Environmental Working Group (EWG): ‘After making billions contaminating the nation’s drinking water with PFAS chemicals, now DuPont will profit off the backs of local governments and taxpayers trying to clean up the mess […] this outrageously cynical move is right on brand for DuPont, which knew decades ago that PFAS chemicals were hazardous to human health but covered it up for the sake of profit’ (Formuzis 2019).

Finally, Greenwash Through CIC

The ‘new DuPont’ has made multiple commitments to the Council. Such commitments include ‘committing to enable millions of people access to clean water by 2030 through leadership in advanced water technology and enacting strategic partnerships’ and implementing ‘holistic water stewardship strategies across all facilities prioritizing manufacturing plants and communities in high-risk watersheds by 2030.’ At the same time, Dupont is allegedly eschewing its legal obligations to pay for the clean-up and damages resulting from the presence of PFAS in the water of towns where Teflon was produced. The emphasis on providing clean water in DuPont’s commitments is a prime example of selective disclosure. To the uninformed reader, DuPont’s commitments appear promising. However, once DuPont’s collective ESG record over the past several decades is accounted for, its claims appear duplicitous. On the Council’s website, DuPont proclaims: ‘Throughout DuPont’s history, we have proven the most valuable and enduring business outcomes are those beneficial to society and the planet.’

Clearly, DuPont does not represent the Council’s values of trust, sustainability, responsibility and fairness. Even if DuPont intends to enact these values going forward, the issue of restorative justice remains. Without taking responsibility for and paying the damages associated with PFAS, it seems highly unlikely a corporation which so recently failed to enact the values of inclusive capitalism could possibly be genuinely motivated to transform the ethics of the private sector. It seems more probable DuPont is attempting to distance itself from its legacy by aligning itself with the Council in a greenwashing public relations move.

Greenwashing Case Study II: BP

Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill

Perhaps the most glaring example of greenwashing among the Council’s stewards is energy company British Petroleum (BP). Under Lord John Browne, BP deliberately cultivated an image portraying itself as an environmental steward and highlighting its investments in renewable energy (Cherry & Snierson 2010). The oil company had been running lucrative but misleading advertising campaigns since 2000, touting slogans such as ‘beyond petroleum’ and ‘the best way out of the energy fix is an energy mix’ prior to its infamous oil spill off the Gulf of Mexico in 2010 (Haley, 2010). In the wake of the spill, the extent of the company’s greenwashing became apparent. BP had been wilfully negligent about safety risks it was taking whilst enjoying a reputation as an ESG leader in its field (Cherry & Snierson 2010). Further, the company invested 93% of its yearly spend into oil and natural gas and only 4.18% into biofuel and solar initiatives, according to Greenpeace U.K, a reality which was clearly misrepresented in its public relations (Haley, 2010).

New management subsequently divested from most of BP’s renewables, further exposing how shallow the company’s commitment to sustainability had been (Haley, 2010). As Cherry and Snierson (2010) note ‘It seems that BP’s benevolence was limited primarily to areas that would be profitable for the firm’s shareholders; it did not engage in CSR beyond that level and importantly did not act in socially responsible ways where there would be no profit or public relations upside.’ BP as it stood a decade ago certainly would not have upheld the CIC’s values of trust, responsibility, and sustainability. In fact, it used stakeholder capitalism largely as a PR front whilst operating on the basis of MSV.

Still Investing in Oil and Gas

More recently, BP was embroiled in yet another greenwashing case. In 2018, ClientEarth argued that BP’s new campaign, the largest global campaign since the Deepwater Horizon Spill, was misleading. The campaign highlighted the company’s efforts to make natural gas ‘cleaner’, and to roll out a network of electric car charging stations, featuring the slogans ‘keep advancing’ and ‘possibilities everywhere’. ClientEarth argued because 96% of the company’s annual spending was invested into oil and gas, the campaign’s focus on BP’s lower carbon products exploited an informational asymmetry between the company and the public (Montague 2020). ClientEarth was found to have a legitimate interest in the complaint by the NCP, a division of the U.K.’s Department of International Trade. BP removed the ads. Lawyer for ClientEarth, Sophie Marjanac said ‘Oil and gas companies are spending millions to convince the public of their social licence to operate and deflect from their role in rapidly heating the planet […] Fossil fuel companies using advertising to mislead the public over their climate impact have been put on notice’ (Montague, 2020). Just two years ago, BP still was not upholding the CIC’s values of trust, responsibility and sustainability.

Just months after the ClientEarth case, BP’s new CEO Bernard Looney announced plans to ‘reinvent’ BP. Although new to the role, Looney is a veteran of BP, having worked for the company for three decades. In February of 2020, he released ambitious plans for BP to reach net zero by 2050 (Doyle, 2020). The plans involve increasing investment in renewables tenfold in the next decade, reducing the carbon intensity of the products it markets by 50% by 2050 and a commitment to no new oil or gas exploration, among other goals (Doyle, 2020). BP’s commitments to the CIC appear to be a duplication of this plan. As one New York Times article notes, ‘The corporate pledges are meaningful, but some aren’t new: BP, for example, restates a commitment to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2050 that it announced in February’ (Ross Sorkin et al. 2020).

Given BP’s history of greenwashing, environmental protection agencies and other stakeholders are justifiably cautious about the company’s new plans. It is likely the transformation is driven to a large extent by its $17.4 billion dollars in total write downs, a strong signal that the value of oil and gas will fall as renewables increase in contribution to global energy use (MacFarlane, 2020). Further, BP’s 2020 outlook predicts that growth in the demand for oil will curb in the next few years. BP’s reinvention is thus just as likely to be commercially motivated as ethically motivated. To avoid the cost of plugging and retiring oil wells after growth declines, BP will divest early and simultaneously cut its emissions (McKenzie, 2019). BP’s decision reflects a rising awareness among corporations that transitioning to a lower-carbon business model may be a necessary survival strategy as global warming increases. BlackRock CEO Larry Fink wrote in his annual letter in 2019 “climate change has become the defining factor in companies’ long-term prospects.”

Commitments to CIC

Divestment is not enough, however. BP’s wells will likely continue to be pumped after BP has divested from them due to the terms of their leases (MacKenzie, 2019). In addition, since BP’s petrol stations stock oil from suppliers other than its own wells, BP may simply end up altering the supply chain without reducing the net amount of oil being extracted and sold (Wockner & Chadwick 2020). Greenpeace thus urges BP to extend its emissions goals to sales as well as production (Wockner & Chadwick 2020). Given BP’s ongoing legacy in oil, the issue of restorative justice is pertinent. It must go further than divesting to actively foster a more sustainable future. Indeed, some of BP’s commitments to the CIC, although small in scale in comparison to its gross carbon footprint, seem to be headed in this direction. BP commits to:

- Help countries, cities and corporations around the world decarbonize, aiming to partner with 10-15 cities and 3 industrial sectors: high-tech and consumer products, heavy transport and heavy industry

- Support the market for Natural Climate Solution [NCS] to grow, aiming to have access to carbon credits from around 100 NCS projects in our portfolio.

- Increase the proportion of investment [they] make into our non-oil and gas businesses, by up to eight-fold by 2025 and 10-fold by 2030 to around $5 billion per year

- More actively advocate for policies that support net zero, including carbon pricing

Still Only 3% in Renewables

Nonetheless, the Council ought to be cautious in its endorsement of BP. In 2019, BP invested only 3% of its annual spend on renewables. Environmentalists are doubtful as to whether BP’s claims are legitimate. Greenpeace U.K notes BP and other big oil companies have ‘used their PR clout and political influence to delay meaningful climate action, sacrificing whole communities and habitats in their pursuit of profit’ in the past (Wockner & Chadwick 2020). Such concerns may not be entirely unfounded.

For example, BP and other big oil companies wrote to the EU as part of the International Association of Oil & Gas Producers (IOGP) in December of 2020 requesting they go against scientific advice and classify fossil fuel gas as a sustainable energy source in their upcoming taxonomy (ClientEarth, 2020). The taxonomy will ‘classify what business activities are deemed sustainable and will help re-orient finance flows toward genuinely green businesses and to avoid greenwashing’ (ClientEarth, 2020). Environmentalists are arguing BP’s signature on the letter, given their new commitments, signals BP is more interested in ‘moving the goalposts’ than engaging in true sustainable practices. Lawyer for ClientEarth Johnny White said: “The gas lobby appears to be doubling down on greenwashing in Brussels: lobbying to water down green investment standards, when it can use the same standards to camouflage continued access to capital for unsustainable fossil gas’ (ClientEarth, 2020). If the IOGP’s demand is met, it could have disastrous environmental consequences, resulting in investments in projects which will produce untenable carbon emissions. The Council risks losing credibility in aligning itself with organisations such as BP, whose actions continue to violate the values of trust, sustainability, and responsibility.

Greenwashing, Faux-ESG and Free-Ridership:

The previous sections focussed on issues with sustainability reporting, particularly the Council’s ability to discern when they are being used as a platform for greenwashing. In evaluating whether a given commitment aligns with the Council’s values: People, Planet, Principles of Governance, and Prosperity (PPPP) and the SDGs is also significant. Without clear frameworks and accountability to guide commitments, organisations may default to free ridership, setting goals which fall short of fulfilling their ethical responsibilities. Faux-ESG and greenwashing by definition require organisations actively promote disinformation about their ESG to foster a socially responsible image. Engaging in free-ridership requires organisations to actively promote their ESG efforts, while avoiding setting goals which require existing practices to be significantly altered.

For example, Allianz’s commitment to ‘fully phase out coal-based business models across [their] proprietary investments and property-casualty portfolios by 2040 at the latest’ seems incongruent with their goal to ‘set long-term climate targets for [their] proprietary investments and business operations in line with the Paris Climate Agreement’s goal to limit global warming to 1.5°C’. While Allianz has made progress toward their commitment to divest from coal, ceasing to ensure new coal projects, their deadline of 2040 does not comply with the goal to limit global warming to 1.5°C.

Developing and urbanising countries favour coal because it is considerably cheaper than natural gas, but emits higher concentrations of carbon dioxide when burned. Ethical concerns over global inequity place constraints on the West’s ability to limit the coal consumption of developing and industrialising countries insofar as it is seen as a necessary means to leverage these countries out of poverty. As such, carbon emitted from coal is projected to be a major contributor to continued global warming over the next decade. As one study noted, “the success of the Paris Agreement and international climate mitigation efforts may therefore depend on curtailing growth of coal‐based energy and emissions in now‐industrializing and urbanizing countries” (Meng et al. 2018, p. 5).

Allianz’s competitor, AXA insurance, has set an example by outlining two dates for divestment from coal-based business models: OECD countries by 2030, and the rest of the world by 2040, which aligns with the Paris Agreement goals (Buberl, 2019). Allianz, which boasts ‘more than 100 million retail and corporate customers in more than 70 countries’ according to the CIC, must follow in AXA’s footsteps if it is to honour its commitment to the CIC to align its climate targets with the Paris Agreement’s target of limited global warming to 1.5°C.

Although Allianz’s commitment matches the values of sustainability and responsibility, it only does so in a limited way. Given that increases in global temperatures above 1.5 degrees Celsius is likely to result in runaway climate change, which will have a catastrophic impact on the world’s biodiversity and the well-being of future generations, corporations like Allianz have an ethical responsibility to ensure their actions align with the Paris Climate accord.

One might argue the CIC’s values are only supposed to offer ethical guidance, while the WEF/IBC’s pillars for sustainable value creation,People, Planet, Principles of Governance, and Prosperity (PPPP), and the SDGs are intended to govern actionable commitments. However, the SDGs are deliberately non-prescriptive to allow for a plurality of approaches. An action might advance the SDGs, but still absolve organisations of the responsibility to act in a timely manner.

The latter dilemma is a collective action problem, insofar as responsibility for advancing the SDGs is diffuse, and individual parties are unlikely to be motivated to undertake costly enterprises to pursue the SDGs. The CIC leaves the degree of change organisations wish to foster to self-determination, allowing them to be highly selective about these goals. Indeed, many of the commitments the stewards have made are simply copied from their existing ESG reports, thus are not new. Unless the CIC introduces a framework for assessing the suitability of stewards’ goals, it risks merely advertising insufficient actions or would have taken place anyway without driving real reforms.

Summary and Recommendations:

Without proper precautions, the Council leaves itself vulnerable to being used – as a platform for greenwashing or ‘faux-ESG’ by companies looking to rebrand themselves or manage their public relations. The Council inherits issues which already plague sustainability reporting, emphasising positive actions without contextualising them against a company’s broader ESG performance. Further, in allowing organisations to determine their own commitments, many of which are simply replications of their existing ESG targets, the Council risks encountering the issue of free-ridership and only partially fulfilling organisations’ stated values. The Council proclaims on its website ‘To date, we have 278 commitments from 44 organisations’. In reality, however, these statistics tell us very little about the Council’s impact as it is difficult to differentiate organisations making real reforms from those simply highlighting their positive environmental and social actions.

If companies whose ethics are in violation of the Council’s core values pose as ‘stewards’ of inclusive capitalism, the movement is likely to further erode social capital and be viewed as yet another disingenuous attempt to salvage the legitimacy of the private sector. Affiliating the Council for Inclusive Capitalism with such companies risks stakeholders viewing the Council’s efforts as part of a larger culture of systemic greenwashing. Failing to adequately address these issues, the Council’s ability to effect real change is likely to be compromised. Further, the CIC may even have a net negative social impact on the common good insofar as it facilitates greenwashing, which violates the values of inclusive capitalism.

The following recommendations aim to safeguard the Council against the latter problems:

- Require sustainability reports in compliance with major frameworks for large organisations: currently, sustainability reporting is voluntary. While the CIC cannot legally obligate the organisations it works with to produce sustainability reports which comply with major standards, such as WEF/IBC, TCFD, SASB and GRI, compliance can be a condition of membership. As formerly noted, such frameworks may not be sufficient to prevent certain forms of duplicity. For example, narrow sustainability reporting boundaries or selectivity may continue to be an issue. However, on February 16th the Council endorsed a new framework released by the World Economic Forum’s International Business Council (WEF-IBC), the first attempt to create common metrics for sustainable value creation.

- Auditing: one of the primary issues with sustainability reporting is that auditing is not mandatory. As suggested above, the CIC could make auditing of sustainability reports a requirement of membership. Professional auditing of companies’ reports in accordance with international frameworks for non-financial auditing such as the International Standard on Assurance Engagement (ISAE) 3000 and the AA 1000 Assurance standard would reduce the risk of companies utilising the CIC as a public relations opportunity. It is worth noting, however, there are several limitations to non-financial auditing. Cho (2019) argues attestation in sustainability reporting lacks the degree of rigour in financial auditing because: a) there is a ‘lack of authoritative bodies like the Securities and Exchange Commission which could add real accountability’, b) the standards lack ‘weight or authority’ and c) non-financial auditing is voluntary and limited in scope, thus more akin to consultancy (Gaetano, 2019).

- Evaluate Organisations’ commitments: put together a team of Council members responsible for reviewing organisations’ commitments to ensure that they align with the Council’s values, the PPPP and the SDGs. Create a framework to guide this process. For example, when evaluating whether a company’s commitments align with the value of responsibility, its efforts to neutralise previous social and environmental externalities should be considered. Likewise, commitments under the ‘Planet’ pillar sustainable value creation ought to align with major environmental agreements, such the Paris Climate Agreement.

- Hold organisations accountable to their commitments: if the statement obtained by Anne Quito is accurate, the Council will be auditing metrics provided by the organisations annually using a scorecard system. To instate further transparency, the Council could contextualise progress against the firm’s overall performance as detailed in their audited sustainability report to give an overall score for each pillar of the PPPP. For example, the Council could factor in both a company’s investments in alternative energy and the carbon footprint of its production process to give an overall score for the ‘planet’ pillar of PPPP. Notably, this would be a complex and administratively costly process.

- Invest in research and public education regarding greenwashing: many of the issues the Council faces are more general issues to sustainability reporting. Funding research on ESG reporting, pledging support for organisations looking to improve existing frameworks and develop new ones, and investing in the development of educational resources for investors, employees, consumers and the general public would a) align with the Council’s value of trust in enabling better disclosure and b) eventually be beneficial in refining the Council’s ability to identify stewards whose overall ESG aligns with their vision. Note the Council has already pledged its support for the formation of a global ESG reporting standard.

References:

‘DuPont, 3M Concealed Evidence of PFAS Risks’. Union of Concerned Scientists, 22 March, 2019, https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/dupont-3m-concealed-evidence-pfas-risks Accessed February 13 2021.

Balch, Oliver. ‘Lady de Rothschild’s road to the Vatican’. Reuters Events: Sustainable Business, Dec. 15 2020, https://www.reutersevents.com/sustainability/lady-derothschildsroad-vatican#:~:text=%E2%80%9CThe%20guidance%20of%20Pope%20Francis,social%20teachings%20of%20all%20faiths.%E2%80%9D. Accessed 13 February 2021.

Bhatia, Aditi. “The corporate social responsibility report: The hybridization of a “Confused” genre (2007–2011).” IEEE transactions on professional communication 55.3 (2012): 221-238.

Brendan, Montague. ‘BP ‘using advertising to mislead the public’’. Ecologist: Informed by Nature, 22 June 2020, https://theecologist.org/2020/jun/22/bp-using-advertising-mislead-public Accessed February 13 2021.

Buberl, Thomas. ‘AXA launches a new phase in its climate strategy to accelerate its contribution to a low-carbon and more resilient economy’. AXA Magazine, 27 Nov. 2019, https://www.axa.com/en/press/press-releases/axa-launches-a-new-phase-in-its-climate-strategy-to-accelerate-its-contribution-to-a-low-carbon-and-more-resilient-economy Accessed February 13 2021.

Carney, Mark. “Inclusive Capitalism: Creating a sense of the systemic.” speech given by Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England, at the Conference on Inclusive Capitalism, London. Vol. 27. 2014.

Catechism of the Catholic Church. Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1994. Print.

Chase, Randall. ‘Court upholds dismissal of Chemours lawsuit against DuPont’. AP News, 17 Dec. 2020, https://apnews.com/article/lawsuits-delaware-environment-courts-us-news-9c2ba2777ab8f5db3d40aa4f0ae8711c Accessed February 13 2021.

Cherry, Miriam A., and Judd F. Sneirson. “Beyond profit: Rethinking corporate social responsibility and greenwashing after the BP oil disaster.” Tul. l. rev. 85 (2010): 983.

Detrixhe, John. ‘The difference between shareholder and stakeholder capitalism’. Quartz, 7 Oct. 2020, https://qz.com/1909715/the-difference-between-stakeholder-and-shareholder-capitalism/. Accessed 13 February 2021.

Doyle, Amanda. ‘BP reveals strategy to reach net zero’. The Chemical Engineer, 7 Aug. 2020, https://www.thechemicalengineer.com/news/bp-reveals-strategy-to-reach-net-zero/#:~:text=FOLLOWING%20its%20announcement%20in%20February,production%20by%2040%25%20by%202030.&text=It%20aims%20to%20have%2050,from%202.5%20GW%20in%202019. Accessed February 13 2021.

Drew, Bryan T., et al. “Salvia united: The greatest good for the greatest number.” Taxon 66.1 (2017): 133-145.

Formuzis, Alex. ‘DuPont Made Billions Polluting Tap Water With PFAS; Will Now Make More Cleaning It Up’. The Environmental Working Group, 12 Dec. 2019, https://www.ewg.org/release/dupont-made-billions-polluting-tap-water-pfas-will-now-make-more-cleaning-it Accessed February 13 2021.

Francis. ‘Address Of His Holiness Pope Francis To The Members Of The Council For Inclusive Capitalism’. Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 11 Nov. 2020, http://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/speeches/2019/november/documents/papa-francesco_20191111_consiglio-capitalismo-inclusivo.html Accessed February 13 2021.

Francis. ‘Fratelli Tutti’. On Fraternity and Social Friendship, 3 Oct. 2020, http://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/encyclicals/documents/papa-francesco_20201003_enciclica-fratelli-tutti.html. Accessed 13 February 2021.

Friedman, Milton. “The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits.” Corporate ethics and corporate governance. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2007. 173-178.

Gaetano, Chris. ‘Rise of Sustainability Reporting Brings Questions of Motivation, Agenda’. The Trusted Professional, 16 Sept. 2019, https://www.nysscpa.org/news/publications/the-trusted-professional/article/rise-of-sustainability-reporting-brings-questions-of-motivation-agenda. Accessed 13/02/2021.

Gillam, Carey. ‘Why a corporate lawyer is sounding the alarm about these common chemicals’. The Guardian, 27 Dec. 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/dec/27/chemicals-dupont-rob-bilott-toxic-america Accessed February 13 2021.

Hinks, Gavin. ‘Narrow sustainability reporting boundaries can amount to greenwashing’. Board Agenda, 21 Jan. 2020, https://boardagenda.com/2020/01/21/narrow-sustainability-reporting-boundaries-can-amount-to-greenwashing/ Accessed February 13 2021.

Hussain, Waheed, “The Common Good”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2018/entries/common-good/

Kirk, Martyn, et al. “The PFAS health study: systematic literature review.” (2018).

Laufer, William S. “Social accountability and corporate greenwashing.” Journal of business ethics 43.3 (2003): 253-261.

McFarlane, Sarah. ‘BP Takes $17.5 Billion Write-Down, Expects Oil Price to Stay Low’. WSJ, 15 June 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/bp-takes-17-5-billion-write-down-expects-oil-price-to-stay-low-11592211169 Accessed February 13 2021.

Meng, Jing, et al. “The rise of South–South trade and its effect on global CO 2 emissions.” Nature communications 9.1 (2018): 1-7.

Miles, Samantha, and Kate Ringham. “The boundary of sustainability reporting: evidence from the FTSE100.” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal (2019)

Morgenson, Gretchen. ‘How DuPont may avoid paying to clean up a toxic ‘forever chemical’. NBC News, 2 March 2020, https://www.nbcnews.com/health/cancer/how-dupont-may-avoid-paying-clean-toxic-forever-chemical-n1138766 Accessed February 13 2021.

Pérez Caldentey, Esteban, and Matías Vernengo. Modern finance, methodology and the global crisis. No. 2010-04. Working Paper, 2010.

Quito, Anne. ‘Pope Francis is backing a new movement to redefine capitalism as a force for good’. Quartz, Dec. 9 2020, https://qz.com/work/1942727/pope-francis-backs-the-Council-for-inclusive-capitalism/ Accessed February 13 2021.

Ross Sorkin, Andrew., Karaian, Jason., de la Merced, Michael J., Hirsch, Lauren and Ephrat Livni. ‘The Pope Blesses Business Plans: A New Initiative Brings the Vatican and CEOs together’. The New York Times, 8 Dec. 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/08/business/ dealbook/pope-vatican-inclusive-capitalism.html Accessed February 13 2021.

Sandberg, Joakim. “Understanding the separation thesis.” Business Ethics Quarterly (2008): 213-232.

The Council for Inclusive Capitalism with the Vatican Announces Support of Convergence Toward Common Metrics and Standards Around ESG and SDG-Aligned Investments. The Council for Inclusive Capitalism, 27 Jan. 2021, https://www.inclusivecapitalism.com/news-insights/the-council-for-inclusive-capitalism-announces-support-of-convergence-toward-common-metrics-and-standards-around-esg-and-sdg-aligned-investments/ Accessed February 13 2021.

Walker, Haley. ‘Recapping on BP’s long history of greenwashing’. Greenpeace U.K., 21 May 2010, https://www.greenpeace.org/usa/recapping-on-bps-long-history-of-greenwashing/ Accessed February 13 2021.

Wockner, Samantha and Mal Chadwick. ‘One of the world’s biggest oil companies has promised to produce much less oil. Here’s what you need to know’. Greenpeace U.K., 19 Aug. 2020, https://www.greenpeace.org/new-zealand/story/bp-oil-update-2020/ Accessed February 13 2021.