CliFin Case Study: The European Green Deal

By Lucas Tse

This CliFin Case Study of The European Green Deal is the fourth part of SPI’s CliFin (Climate Finance) Series

Introducing the European Green Deal

The European Green Deal (EGD) was first publicised in 2019 when President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen committed to the goal of European climate neutrality by 2050. She called the announcement Europe’s ‘man on the moon’ moment. In December 2019, the Commission set out the EGD for the EU and its citizens, calling climate action ‘this generation’s defining task.’ A number of reports and press releases in the first months of 2020 have provided further detail on the EGD: its institutional mechanisms and the intermediate goal of 50-55% cut in emissions by 2030 (compared to 1990 levels). The EGD is by no means the first comprehensive ‘deal’ to address climate change. Columnist Thomas Friedman first used the term ‘Green New Deal’ in 2007, and the UK Green New Deal Group released its report in 2008. More recently, the plan for a Green New Deal has received significant attention in the American context.

Voices in governance, economics, as well as climate action have discussed the EGD. UN Secretary-General António Guterres praised the EGD but advocated more ambitious goals: ‘If we just go on as we are, we are doomed.’ Economist Jeffrey Sachs also reviewed the EGD positively, while pointing out financing (both private and public) as one of the key challenges to successful implementation. A Working Paper from the Finish Institute of International Affairs points toadequate financial endowment as a key component of the EGD in the post-pandemic context. This case study describes how finance features in the EGD’s overall strategy; it then outlines the specific mechanisms proposed by the European Commission towards climate-friendly investment and a just transition; finally, it reviews major ethical issues that lie in financing the EGD.

The EGD’s Financial Strategy

While the primary focus of the EGD is in decarbonising Europe, it inevitably involves economic and financial considerations. This section describes the core elements of the EGD’s financial strategy, of which there are two: an investment plan, which includes both public and private funds; and a just transition mechanism that ensures equitable effects in the process of decarbonisation.

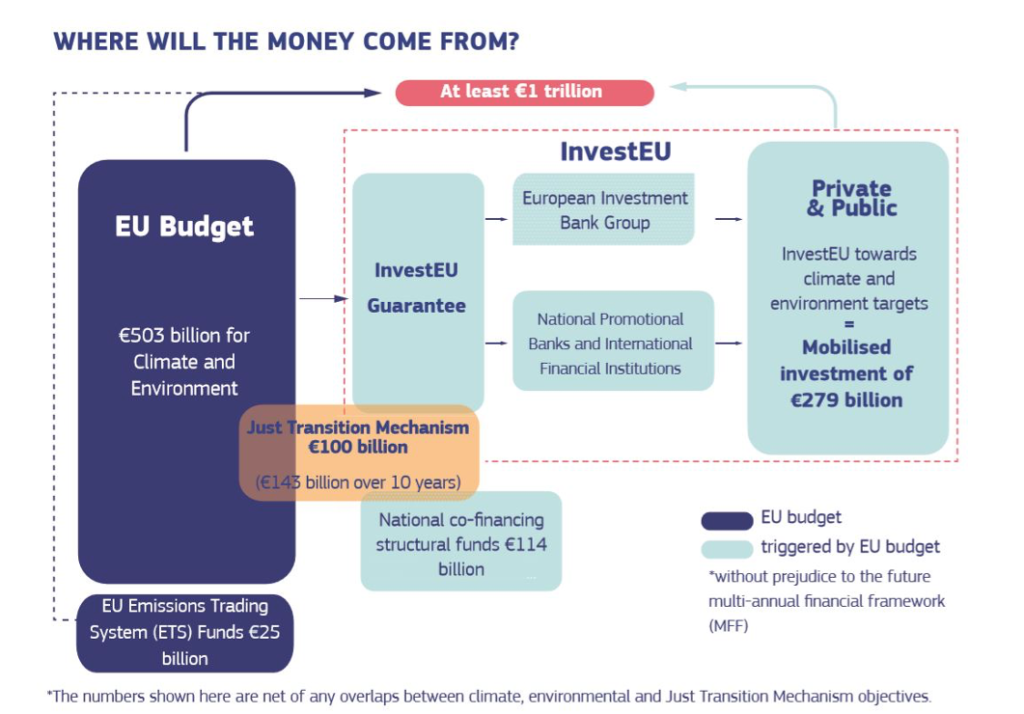

The European Commission is mobilising at least €1 trillion of sustainable investments over the next decade. It identifies a ‘green investment gap’ between currently mobilised resources and the amounts required to meet climate-related targets. The Sustainable Europe Investment Plan meets such additional need. The Commission acknowledges the large scale of investment needs: achieving current 2030 climate targets requires €260 billion in additional investments annually. (An in-depth analysis by the European Commission in 2018 suggests that these figures are most likely underestimations, since its calculations do not include ‘investment in roads, railways, ports and airports infrastructure and in systems facilitating sharing of vehicles etc […] investment or hidden costs related to behavioural or organisation structural changes or in sectors outside energy are not part of the calculation of investment expenditures either.’) The EGD’s investment plan includes public funds, starting with the next EU budget which will run from 2021 to 2027. The Commission has proposed the allocation of 25% (up from 20%) of the budget to climate action. It will also involve the multilateral European Investment Bank (EIB), which has announced the doubling of its climate investment target from the current level of 25% to 50% in 2025. The idea is to provide a budget guarantee to the EIB for risk-taking in climate-related investments and to crowd in institutional and private investors. Finally, the Commission has devised a taxonomy for sustainable finance, with clear rules for green investments.

The EGD’s investment plan also includes the mobilisation of private funds. This is crucial given the limited resources within the EU budget for large-scale investment. In other words, the EGD will have to devise a framework to incentivise ‘green investment’ from the private sector and thereby to bridge the gap between climate policy and the available private resources. The main financial vehicle at the Commission’s disposal is InvestEU, which is the successor programme to the European Fund for Strategic Investments (known colloquially as the ‘Juncker Plan’) and thirteen other EU financial instruments. It came into being in 2018 and its main purpose is to leverage the Commission’s limited resources—through EU budget guarantees—to unlock private funds. If carried out successfully, this will have two primary benefits. First, it can direct private resources towards climate-related operations and technologies, which are often riskier and more capital-intensive. Second, it can reduce the potential crowding-out effect and maintain market-driven incentives.

(Source: European Commission)

In addition to the Sustainable Europe Investment Plan, the EGD contains the Just Transition Mechanism (JTM), which targets the most vulnerable regions and sectors during the decarbonising transition. The JTM itself contains three pillars. First, there is the Just Transition Fund, which begins with €40 billion from the EU budget supplemented with national co-financing, thus potentially reaching €107 billion in capacity. Region-specific grants will target economic needs in the climate transition—such as upskilling, SME subsidies and startup funding. Second, there will be a just transition scheme within InvestEU. This scheme will mobilise up to €45 billion of dedicated investments. It will focus on directing private funds towards energy and transport projects in areas most in need of economic transition. Third, there will be a public sector loan mechanism from the EIB with EU budget guarantees. This will make funds available for governments towards climate-related operations, such as heating and building renovation. In its original announcement in December 2019, the Commission had stated that ‘this transition must be just and inclusive. It must put people first, and pay attention to the regions, industries and workers who will face the greatest challenges.’

Reviewing the EGD: Ethics in Climate Finance

What are the ethical issues at play in the financing of the EGD? Commentators have pointed to a number of issues with the EGD—including insufficient funds, the need for coordinating investment with fiscal and monetary policy, and the methods for investment accounting. This section reviews three themes of ethical concern: the conceptualisation of decarbonisation with regards to economic growth; the possibility of ‘greenwashing’; and the question of distributive justice in the processes of climate change and climate action.

The question of decarbonisation and economic growth is the broadest of the three. The EGD has revived existing debatesabout the compatibility of climate action with current economic systems. In the 1970s, economist E.F. Schumacher’s Small is Beautiful questioned the status of economic growth as the holy grail of modern life, as did the Club of Rome’s famous ‘Limits to Growth’ report. Ethics-based approaches have cautioned against the overemphasis on economic growth given the importance of other ethical concerns, such as solidarity, poverty, and ecology. On the other hand, economists such as Benjamin Friedman and Tyler Cowen have argued for the positive moral consequences of economic growth—for example, that rising standards of living lead to more open and tolerant societies. Commentators on the EGD have debated its fundamental mission, bringing such debates into the context of climate policy and finance. Recent empirical research has suggested an ethical dilemma between the priorities of economic growth and environmental sustainability. A Policy Contribution from the economic thinktank Bruegel emphasises the overarching objective of the EGD should be decarbonisation and redistribution rather than economic growth. Economist Ann Pettifor’s writing on a ‘Green New Deal’ argues against the binary framing of growth and degrowth, adopting instead the approach of the steady-state economy.

The question of ‘greenwashing’ also looms large as a concern for both private and public investment, even though the EGD is not a brand in the commercial sense. What is the proper definition of climate-related investment, and how are decision-making bodies accountable to the public? While studies on greenwashing have focused on institutional drivers within corporate contexts, there is also a need to review the ethical context of public investment. The EU has previously faced accusations of greenwashing in sustainable development. Leaders of the DiEM25 movement have questioned the public-private financing model and called the EGD a “greenwashed” status quo—in particular, the investment plan does not reduce risk, instead providing private finance with new opportunities while putting the risk burden on the public. Daniela Gabor, professor of economics at UWE Bristol, has pointed to the effects of lobbying on the EGD: ‘the first greenwashed social pact between regulators and carbon financiers, between Brussels and local elites.’ The Corporate Europe Observatory has referred to the systematic lobbying of the fossil fuel industry on the EGD. The report points out that the ‘removal’ of carbon allows for continued emissions from oil companies such as Eni and Shell within the carbon neutrality framework; and that while the EGD calls for phasing out of coal, industry has successfully lobbied for the increased role of gas.

Commentators have connected the effects of lobbying with the phenomenon of ‘greenwashing,’ in which EGD projects may end up with investments that are climate-friendly only in name. The think tank Counter Balance, which focuses on public investment banks, has reported that the predecessor instruments to InvestEU have a mixed record in green finance—for a three year period, almost 75% of projects in the transport sector were high-carbon, and a number of energy projects were based in fossil fuels. There is need for stricter definitions of sustainability in InvestEU. The European Commission’s Technical Expert Group has proposed a taxonomy in which three kinds of economic activities are considered green: sustainable, transition and enabling. The taxonomy draws on a broader range of expertise than private environmental (ESG) ratings, but the eligibility for green finance is loose, and there is mounting pressure to review the opportunities for ‘greenwashing.’ Analysts have pointed to the role of lobbying in including a very broad range of ‘green assets’ in the taxonomy. Economist Servaas Storm has further cautioned against providing additional profit-making opportunities to fossil-fuel financiers—thus rewarding those already holding large investments.

Thirdly, at the core of the EGD is a question about the disparate effects of climate change as well as climate action—a question about distributive justice that is at least as old as Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. In the EU context, social solidarity is a key ethical principle of what is called the ‘social market economy.’ A report from the thinktank Bruegel suggests that there is a need for climate policy today to be intrusive, in order to meet decarbonising targets; but the distributive side-effects can incur backlash. Social psychologists have analysed the significance of perceived inequality—especially the categorisations of ‘haves’ and ‘have nots’ in the context of increased fuel prices—to the gilets jaunes protests in France. In April 2020, Flemish nationalists blocked the Belgian government from affirming the EGD, arguing that insufficient attention to regional inequalities renders it a ‘mean deal’: ‘Flanders will not agree with the distribution of resources as currently proposed.’ Further discussions between EU climate ministers in June 2020 revealed regional divisions between member states, especially on the possibility of deepening inequalities. Such distributive effects will most likely be exacerbated by the coronavirus-induced economic downturn: the IMF has projected negative growth of 7.5% for the Euro area in 2020.

Regions and communities will not experience the climate transition in the same way. For example, a 2018 report from the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre acknowledges that the loss of coal jobs could be highly impactful on specific regions, even if coal is not a substantial industry in Europe today. By 2030, one area of Poland could lose up to 41,000 jobs and a number of regions could each lose more than 10,000 jobs. Experts on southeast Europe have further pointed out that the region does not have the same ‘starting point’ as northwest Europe and has a number of obstacles in embracing climate action. They conclude that cash injections will not be sufficient; the EGD must contain a holistic approach to regional diversity within Europe. More broadly, specific sectors are likely to decline dramatically in the climate transition—fossil fuel industries, energy-intensive manufacturing, and some forms of transport. While these jobs may in theory be replaced by others in sectors such as renewable energy and construction, the EGD will have to prove the ‘economic case’ by coordinating national policies to maintain maximal employment. The ethics of transitioning to ‘green jobs’ is now a necessary topic for discussion.

Scholars in public health and environmental sustainability have supported a triple win model, such that climate policy results in health, equity, and environmental sustainability. Frans Timmermans, Executive Vice-President of the European Commission’s Executive Vice-President, has stated that ‘we must show solidarity with the most affected regions in Europe, such as coal mining regions and others, to make sure the Green Deal gets everyone’s full support and has a chance to become a reality.’ But what is the ethical basis for such a principle of solidarity? The principle requires citizens to see other as part of a shared community—in that sense, each climate strategy already contains within it a notion of solidarity. For example, 2/3 of revenues from carbon levies in Switzerland are transferred back to the population in lump sums. In British Columbia, carbon tax revenue has been directed towards tax relief for low-income individuals, in addition to cash transfers. The EGD’s Just Transition Mechanism is therefore a case study in how the principle of solidarity can be applied towards climate policy as well as the distributive effects of structural change in the economy.

Conclusion

Implementation of the EGD must now take place in the context of post-Covid recovery. In March 2020, a report from the Centre for European Policy Studies stated that EGD proposals can be integrated with general economic recovery. While carbon emissions have temporarily fallen in early 2020, other commentators are less sanguine. Francesca Colli, a Research Fellow at the Egmont Institute for International Relations, has called this crisis a ‘make or break’ moment for climate action in Europe—miscalculated public investments could exacerbate socio-economic inequality and thwart climate action. Other commentators have called upon the Commission to stipulate ‘green conditions’ so that governmental and intergovernmental aid accord with a low-carbon agenda. The pandemic has clearly challenged solidaristic decision-making in the EU; by July 2020, earmarked funds for climate action were cut for economic recovery, although negotiations are still ongoing.

At the same time, Europe remains a potential leader for climate finance. The EU has a strong track record in reducing its emissions while maintaining economic growth. Its GDP grew by 61% between 1990 and 2018, while its emissions fell by 23%. The need for a ‘green recovery’ is being discussed from the UK to Korea and Africa—the ‘Brussels effect’ of a race to the top, as observed in other areas such as data ethics, continues to be a possibility for European climate policy.