Are Museums Right to Refuse Sackler Money?

By Sariththira Selvakumar

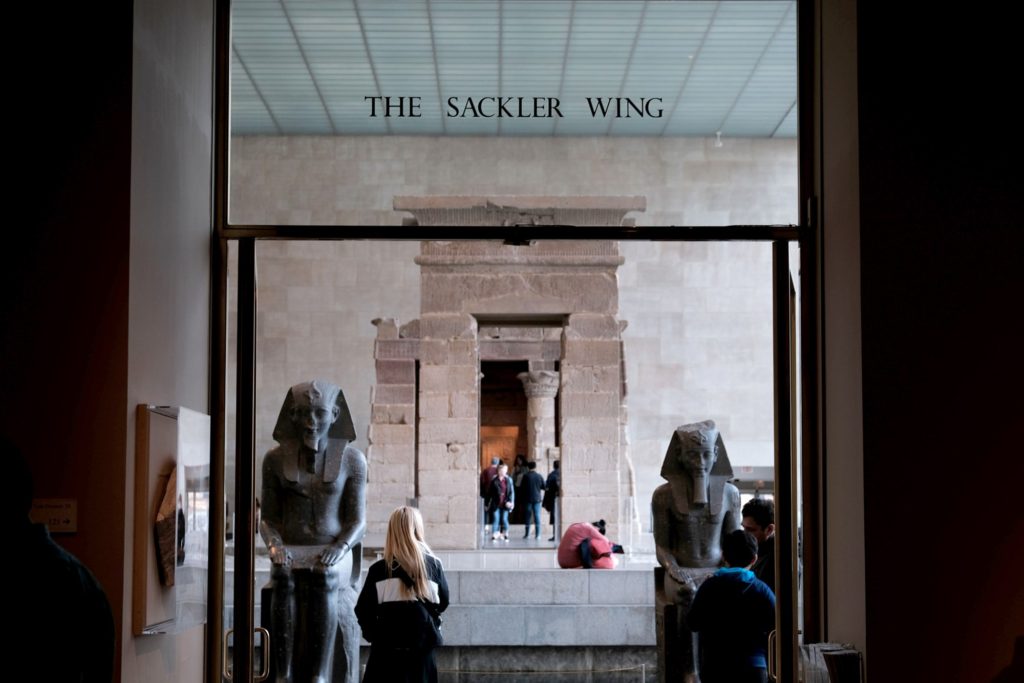

Museums, including the Tate in London, the National Portrait Gallery in London, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, have refused donations from the Sackler family, the owners of Purdue Pharmaceuticals. The institutions have taken this decision due to the numerous lawsuits filed against Purdue Pharmaceuticals for its involvement in the opioid crisis in the United States. The museums were correct to reject donations from the Sackler family given the problematic business dealings of Purdue Pharma and the unethical means through which the Sackler family acquired their wealth.

Purdue Pharmaceuticals Beginnings

Raymond and Mortimer Sackler purchased Purdue Pharmaceuticals (formerly known as Purdue Frederick Co.) 1952 and the Sackler family are still full owners the company. Arthur Sackler, the older brother, was crucial in helping Purdue Pharma advertise efficiently and develop its marketing strategies. Arthur Sackler’s research was pivotal in identifying a gap in the market for long term chronic pain relief. His foresight led to Purdue developing a pill for pain relief named MS Contin – “a morphine pill with a time release-formula” (Frazier, 2014). Once the patent for MS Contin expired, Purdue created a new pill with time-release properties called OxyContin and released it in 1996.

Promoting OxyContin Sales

In order to push sales of OxyContin and cement the reputation of Purdue Pharma amongst doctors, Purdue organised over 40 national ‘pain-management and speaker-training conferences’ between 1996 and 2001 (Bourdet, 2012). These conferences hosted over 5,000 healthcare professionals, from physicians to nurses with Purdue covering all the costs for those attending. Purdue also offered a free 7-30 day trial of OxyContin.

Up until this point, pain-relief medication was only prescribed on a short-term basis for cancer sufferers or those in palliative care. Doctors saw OxyContin as some form of “wonder drug” and would prescribe the medication to patients with debilitating chronic pain (Bourdet, 2012).

Another conspicuous way through which Purdue increased the sales of OxyContin was by using “marketing data to influence physicians’ prescribing” (Zee, 2009). Drug companies form profiles on the prescribers and individual physicians which allows them to observe prescribing habits of doctors. After collecting this data, Purdue targeted doctors who prescribed the highest amount of opioids and those who had patients with chronic pain (Zee, 2009). Tactics such as these, helped Purdue increase its profits from $45 million in 1996 to $1.5 billion in 2002, and around $3 billion by 2009 (Eban, 2011).

Besides spending large sums of money to strengthen ties with physicians, Purdue also gained their support by providing them with false information. The company stated there was a less than 1% chance of people becoming addicted to OxyContin (Meier, 2003). Purdue attributed this low addiction rate to the fact that OxyContin had slow-release properties which lasted 12 hours. The company surmised patients would not have to take as many pills frequently for pain relief. Furthermore, Purdue used studies by Porter and Jick (1980) and Perry and Heidrich (1982) to demonstrate that 4 out of 11,882 patients in the first study and no patients out of 10,000 in the second study experienced addiction due to the drug.

Yet, many more studies prove that in the treatment of chronic-pain unrelated to cancer, there is a “high incidence of prescription drug abuse” (Zee, 2009). Those who used OxyContin quickly found that by peeling back the plastic coating on the pill, they could crush it into a powder or dissolve it in water. This enabled them to inject, snort or inhale the drug (Lopez, 2018). Three Purdue executives plead guilty to charges of misleading doctors and patients about how addictive OxyContin could be and misbranding OxyContin as being “abuse-resistant” (Mariani, 2015). As a result, in 2007 Purdue paid $600 million in fines. The three executives had to complete 400 hours of community service in drug treatment programs and were sentenced to three years probation (Meier, 2007).

New OxyContin Formulation

In August 2010, Purdue Pharmaceuticals released a version of OxyContin it claimed was abuse-deterrent. It would be difficult for users to dissolve or crush the substance, thus discouraging people from injecting or inhaling it.

The New England Journal of Medicine conducted a study to determine whether the newly formulated version actually lived up to its claims. They used “self-administered surveys that were completed anonymously by independent cohorts of 2566 patients with opioid dependence” (Cicero and Ellis, 2012) and collected the data between 1 July 2009 and 31 March 2012.

The findings of the study show the abuse of OxyContin reduced by 16%. In interviews conducted with some of the participants, the study found that 24% of people managed to defeat the “tamper-resistant properties of the abuse-deterrent formulation” (Cicero and Ellis, 2012). On the other hand, 66% of people switched to a different opioid, with heroin being the most cited response. This finding was also reported in a newer working paper. The study added that deaths due to heroin were higher in areas where access to heroin and other opioids was easier before the reformulation of OxyContin – ultimately “each prevented opioid death was replaced with a heroin death” (Evans, Lieber and Power, 2018).

Additional Lawsuits Against Purdue Pharmaceuticals

The lawsuits against Purdue continue and they face nearly 2000 at present. Almost every state in the US now has a lawsuit filed against Purdue for its contribution to the opioid crisis and what this meant for the state. Two of the most notable lawsuits have been from Oklahoma and Massachusetts.

Oklahoma

The allegation put forward by Oklahoma Attorney General Mike Hunter claimed that Purdue had “violated Oklahoma law by deceptively marketing its opioid pain medications – as well as opioid products generally – so as to overstate their efficacy and falsely downplay the associated risk of addiction, which resulted in an opioid crisis and public nuisance in the State of Oklahoma” (Sullivan, 2019). Hunter had sought $20 billion in damages against various pharmaceutical firms, one of which was Purdue (Bebinger, 2019). Purdue agreed to pay a $270 million settlement with Oklahoma in line with the charges.

Massachusetts

The lawsuit filed by Massachusetts is particularly notable as it is the first lawsuit that names members of the Sackler family in the complaint. Up until this point, the Sackler family have presented themselves to be at arm’s length from Purdue Pharma and its activities. Instead, lawsuits have been filed against Purdue. This lawsuit might change the Sackler family’s accountability.

The papers presented by Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey state that Richard Sackler “embraced a plan to conceal how powerful Oxycontin was” in a bid to increase sales (Feeley, 2019). The documents also state that Richard Sackler regularly asked for sales reports and was actively involved in coaching people on how to push OxyContin to doctors. In an interview with PBS NewsHour, New Yorker journalist Patrick Radden Keefe stated the documents also called out Richard Sackler for sending emails outlining how to deal with the deaths of people from OxyContin. In the emails, Sackler provided a guideline to deal with OxyContin related deaths. The narrative was to say these people died due to their own addiction, thereby blaming the victims (PBS Newshour, 2019). Purdue has asked Healy to drop these allegations by labelling them “misleading and inflammatory” (Raymond, 2019).

Furthermore, the complaint alleges that the company aimed to profit from the addictive drug. The complaint claims that Kathe Sackler secretly pitched a plan to expand Purdue’s activities to form a drug called Suboxone to treat those addicted (Bebinger and Willmsen, 2019). According to the lawsuit, Purdue staff labelled this endeavour as an attractive market and predicted that “40-60 per cent of patients buying Suboxone for the first time would relapse and have to take it again” – increasing revenues(Bebinger and Willmsen, 2019).

Those Philanthropic Sacklers

The Sackler family have made donations to institutions globally for decades. This includes museums and universities (for example Oxford University’s Sackler Library and Columbia University’s Sackler Institute). Such acts of philanthropy have been a way for the Sackler family to solidify their contribution back to society and the arts. But various beneficiaries have rejected donations from the Sackler family amidst the numerous lawsuits filed against Purdue Pharma for its contribution to the opioid crisis.

Examples of rejected donations and gifts

- March 2019: Tate Art Galleries in London and the Guggenheim in New York decide they will no longer accept donations and gifts from the Sacklers (Marshall, 2019).

- March 2019: The National Portrait Gallery in London decides to “not proceed” with a £1 million grant from the Sackler family (Bailey, 2019).

- May 2019: The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City says it too will not accept gifts from the Sackler family as the gifts are “not in the public interest, or in our institution’s interest” (BBC, 2019a). The Met states, however, it will not remove the Sackler name from the Sackler Wing (BBC, 2019a).

Ethics Analysis

When we ask if museums are morally right to reject donations from the Sacklers, we should ask whether it is right to benefit from wealth derived from activities that cause harm to people.

An ethical approach suitable for this case is utilitarianism. This moral theory proposes that the consequences of an action are analysed to determine whether this action is ethical. The goal is to ensure more good than harm results from the action (Tan Bhala, 2019). The Institute of Fundraising in the United Kingdom takes this stance (Ricketts, 2018). A first quick glance at the case study may suggest that museums can accept Sackler family donations. The money helps fund museum activities, offers art to the public, and contributes to cultural development. However, a deeper utilitarian analysis shows that Purdue’s actions were unethical. The Sacklers, particularly David and Kathe Sackler, were involved in decision making at Purdue, and they are implicated in the unethical activity. The sale of OxyContin resulted in loss of human life and destruction of families and communities. All for the sake of wealth accumulation. Accordingly, the utilitarian approach would judge accepting donations from the Sacklers as unethical.

Drug Dealers: El Chapo and the Sacklers

Jason Smith (2015) draws an interesting and compelling argument to further illustrate the immorality of Purdue Pharmaceuticals and its practice, as well as the Sackler family who have profited greatly and endorsed the company’s activities. In his article, Smith (2015) draws a comparison between Chapo Guzman and the Sackler family. He outlines how people shun and vilify the atrocities the Sinaloa Cartel (run by Guzman) commit. That is how Guzman and the Cartel should be viewed given the violence the cartel they fuel, the poverty they perpetuate, and the killings due to narcotics sales.

El Chapo (full name Joaquin Archivaldo Guzman Loera) founded the Sinaloa cartel in 1989. The cartel had a decentralised structure. There is no direct chain of command that links the selling of drugs on the street to the Sinaloa cartel (Keefe, 2012). In fact, there is no accurate estimate of how many people work for the cartel, with many people working “for the cartel but outside it” (Keefe, 2012). For example, the cartel sells its drugs to wholesalers who then go on to distribute it. After making its way through the “drug food chain”, the drugs find their way into the hands of a local drug dealer (Smith, 2015).

The cartel’s decentralised structure helped Guzman’s control of the drug trade to continue for a long time. Bribery elevated the drug trade further. Keefe (2012) retells how a former police officer who acknowledged he worked for the Sinaloa cartel, responded that the drug cartels had ‘all’ the police on the payroll. After Guzman’s first arrest in 1993, he was kept in a fortified prison. However, Guzman had “most of the facility on his payroll” (Keefe, 2012) and continued life as usual from within prison. Guzman could send orders to his brother and host lavish parties from within his cell. Eventually, Guzman was smuggled out (Sommerlad, 2019); this would be the first of his two escapes before his third, and presumably final arrest, in 2016.

Federal authorities estimated that Guzman earned around $13 billion during his heyday (Falk, 2019), although all estimates are speculative since there is no accurate disclosure made by the cartel of its profits (Keefe, 2012).

Guzman is now facing life in prison plus thirty years after having been found guilty of all seventeen counts (BBC, 2019b). Additionally, Guzman has to pay $12.6 billion dollars in forfeiture (BBC, 2019b). This arrest comes after two previous arrests, both of which he escaped – the first through bribing prison officers and the second by escaping through a tunnel (Sommerlad, 2019).

Smith (2015) points out that this is not the standpoint taken when it comes to the Sackler family. The Sackler family, like Guzman, has profited from the deaths of those addicted to OxyContin and in some ways indirectly aided the growth in the use of heroin. For example, in 2017, 67.8% of drug-related overdoses were due to opioids (CDC, 2019). The Sacklers also facilitated the growth of El Chapo because, given the high cost of OxyContin, those addicted to OxyContin turned to street heroin to achieve the same high for a cheaper price (Falk, 2019).

Purdue Pharma did not use bribes in order to market OxyContin. Purdue compiled data to identify physicians and doctors who would prescribe their drug. They provided misinformation regarding the addictiveness of OxyContin to ensure the prescription of the drug, in turn contributing to a horrific opioid crisis. The Sackler family pocketed the profits from selling OxyContin.

Yet, unlike Guzman, there is no comparable sentencing for their crimes. Even in the 2007 case, despite paying a sum and receiving a sentence of 400 hours of community service, the lawsuit did not see any of the 3 executives incarcerated. In contrast, an addict in Florida charged with possession of OxyContin without a prescription received a three-year sentence (Smith, 2015). Like the Sinaloa cartel, the number of people implicated in the marketing ploys of Purdue Pharma extends beyond the Sackler family. However, unlike the cartel, where Guzman has been charged for his crimes, the Sackler family continue to evade any form of accountability for the opioid crisis. This exemplifies how the Sackler family are not vilified in the same way, instead, their ‘philanthropy’ is praised and celebrated.

Accepting donations from the Sackler family allows them to continue reputation washing because family members are seen as philanthropists. Attaching the Sackler name to institutions allows the display of their name and places their legacy in a positive light. Burnishing the family name ignores the deaths of OxyContin users, the families destroyed by OxyContin, and the damage OxyContin has done to communities. Purdue Pharma spread lies and misinformation at the expense of people’s lives. Continuing to accept Sackler donations ignores the consequences of the family’s drug dealing, and is thus, unethical.

Bibliography

Bailey, M. (2019) London’s National Portrait Gallery and Sackler Trust to ‘not proceed’ with £1m Grant. The Art Newspaper. Available at: https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/london-s-national-portrait-gallery-rejects-gbp1m-grant-from-sackler-trust [Accessed 15 July 2019]

Bebinger, M. and Willmsen, C. (2019) Lawsuit Details How the Sackler Family Built An OxyContin Fortune. NPR.Available at: https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/02/01/690556552/lawsuit-details-how-the-sackler-family-allegedly-built-an-oxycontin-fortune?t=1564013909660 [Accessed 22 July 2019]

Bebinger, M. (2019) Purdue Pharma Agrees to £270 Million Opioid Settlement With Oklahoma. NPR. Available at: https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/03/26/706848006/purdue-pharma-agrees-to-270-million-opioid-settlement-with-oklahoma [Accessed 20 July 2019]

BBC. (2019a) New York’s Met Museum to Shun Sackler Family Donations. BBC. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-48288803 [Accessed 20 July 2019]

BBC. (2019b). El Chapo trial: Mexican Drug Lord Joaquín Guzmán Gets Life in Prison. BBC. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-49022208 [Accessed 03 August 2019]

Bhala, T. K. (2019) The Philosophical Foundations of Financial Ethics. In: Lastra, R. M., Constanza, A. R. and Blair, W. (2019) Research Handbook on Law and Ethics in Banking and Finance. Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 2-24.

Bourdet, K. (2015) How Big Pharma Hooked America on Legal Heroin. Vice. Available at: https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/jppbxk/how-big-pharma-hooked-america-on-legal-heroin [Accessed 20 July 2019]

CDC. (2017) Drug Overdose Deaths. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html [Accessed 22 July 2019]

Cicero, T. and Ellis, M. (2012) Effect of Abuse-Deterrent Formulation of OxyContin. The New England Journal of Medicine, 367, pp. 187-189.

Eban, K. (2011) Oxycontin: Purdue Pharma’s Painful Medicine. Fortune. Available at: https://fortune.com/2011/11/09/oxycontin-purdue-pharmas-painful-medicine/?source=post_page————————— [Accessed 13 July 2019]

Evans, N. W., Lieber, E. and Power, P. (2018) How the Reforumlation of OxyContin Ignited the Heroin Epidemic. NBER Working Paper 24475. The National Bureau of Economic Research.

Falk, W. (2019) El Chapo’s Business Partner. The Week. Available at: https://theweek.com/articles/819626/el-chapos-business-partner [Accessed 02 August 2019]

Feeley, J. (2019) Opioid Maker Purdue Asks Judge to Toss Massachusetts Drug Suit. Bloomberg. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-03-04/opioid-maker-purdue-asks-judge-to-toss-massachusetts-drug-suit [Accessed 22 July 2019]

Frazier, I. (2014) The Antidote: Can Staten Island’s middle-class neighbourhoods defat an overdose epidemic? The New Yorker. Available at: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/09/08/antidote?source=post_page————————— [Accessed 17 July 2019]

Gounder, C. (2013) Who is Responsible for the Pain-Pill Epidemic? The New Yorker. Available at: https://www.newyorker.com/business/currency/who-is-responsible-for-the-pain-pill-epidemic [Accessed 03 August 2019]

Heidrich, G. and Perry, S. (1982) Management of pain during debridement: a survey of U.S. burn units. Pain, 13(3), pp. 267-280.

Jick, H. and Porter, J. (1980) Addiction rare in patients treated with narcotics. The New England Journal of Medicine, 302(2), pp. 123

Keefe, P, R. (2012) Cocaine Incorporated. The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/17/magazine/how-a-mexican-drug-cartel-makes-its-billions.html [Accessed 03 August 2019]

Lopez, G. (2018) The Maker Of OxyContin Tried to Make it Harder to Misuse. It May Have Led to More Heroin Deaths. Vox. Available at: https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2018/4/16/17234008/opioid-crisis-oxycontin-abuse-deterrent-heroin [Accessed 23 July 2019]

Mariani, M. (2015) Poison Pill: How the American Opiate Epidemic was Started by one Pharmaceutical Company. Pacific Standard. Available at: https://psmag.com/social-justice/how-the-american-opiate-epidemic-was-started-by-one-pharmaceutical-company [Accessed 16 July 2019]

Marshall, A. (2019) Tate Galleries Will Refuse Sackler Money Because of Opioid Links. The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/21/arts/design/tate-modern-sackler-britain-opioid-art.html [Accessed 16 July 2019]

Meier, B. (2007) 3 Executives Spared Prison in OxyContin Case. The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2007/07/21/business/21pharma.html?mtrref=www.google.com [Accessed 20 July 2019]

PBS Newshour (2019) Behind Purdue Pharma’s Marketing of OxyContin. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V-jxKPpMvmA [Accessed: 20 July 2019].

Raymond, N. (2019) Purdue’s Sackler Family Fights ‘Inflammatory’ Massachusetts Opioid Case. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-opioids-litigation/purdues-sackler-family-fights-inflammatory-massachusetts-opioid-case-idUSKCN1RE27A [Accessed 20 July 2019]

Ricketts, A. (2018) Ethics is not the decisive factor in rejecting donations, says IoF guide. This Sector. Available at: https://www.thirdsector.co.uk/ethics-not-decisive-factor-rejecting-donations-says-iof-guide/fundraising/article/1463813 [Accessed 10 July 2019]

Smith, J. (2015) Kingpins: OxyContin, Heroin, and the Sackler-Sinaloa Connection. Medium. Available at: https://medium.com/@jasisrad/kingpins-1fa9331c705d [Accessed 19 July 2019]

Sommerlad, J. (2019) El Chapo: Who is the Mexican drug baron and Sinaloa cartel kingpin and how was he brought to justice? The Independent. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/el-chapo-trial-joaquin-guzman-sinaloa-cartel-drug-wars-mexico-cocaine-a9008831.html [Accessed 04 August 2019]

Sullivan, T. (2019) Purdue Pharma Agrees to Pay $270 Million to Oklahoma to Settle Case Involving Deceptive Marketing Practices of Opioid Painkillers Representing 1.2% of the Total Potential State Liability. Policy & Medicine. Available at: https://www.policymed.com/2019/04/purdue-pharma-agrees-to-pay-270-million-to-oklahoma-to-settle-case-involving-deceptive-marketing-practices-of-opioid-painkillers-representing-1-2-of-the-total-potential-state-liability.html [Accessed 22 July 2019]

Zee, V. A. (2009) The Promotion and Marketing of OxyContin: Commercial Triumph, Public Health Tragedy. Am J Public Health, 99(2), pp. 221-227