ANZ, Deutsche Bank, Citi: Criminal Cartel Case

By: Harry Cui

Australia’s Competition Commission has brought criminal cartel charges against ANZ, Deutsche Bank and Citigroup. The case underlines the significance of financial stability and the role of equity. The trial encroaches on past traditions and may forge new legal precedents for ethics and underwriting in Australia. Although the current financial thinking is dominated by deontological thought, deviation from the ethics of law is occasionally required.

Key Parties

The Prosecutor: ACCC

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) is an independent statutory agency responsible for promoting competition and fair trade in Australia.[1]The Commission was created by statute in 1995.[2]It employs 874 members of staff and is chaired by Rod Sims.[3]One of the Commission’s chief functions is to investigate potential cartel activity and take appropriate action against illicit cartel involvement.[4]Although the purview of the ACCC extends to all breaches of anti-competitive and anti-consumer conduct, the recipients of its sanctions are primarily large commercial parties.[5]The ACCC can bring civil action in court against offending parties. Criminal cartel litigation is handled by the Attorney-General’s department on its behalf.[6]

The Accused

ANZ

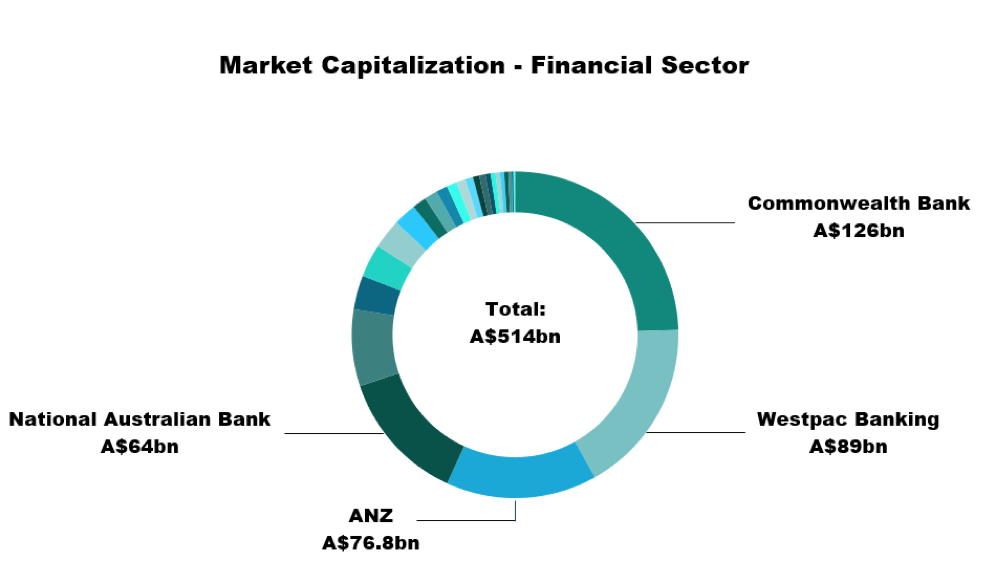

The Australia and New Zealand Banking Group (ANZ) is the third largest bank in Australia.[7]It is colloquially recognised as one of the “big four” banks in the country which accounts for 70% of the financial sector market share.[8]It provides a full range of banking services for both commercial and retail customers. ANZ is a publicly listed company and operates in 34 countries.[9]Due to its size and extensive presence, it is an integral part of the Australian economy and is dubbed as one of the “four pillars.”[10]

The “big four’s” market capitalization in Australia[11]:

Deutsche Bank AG

Deutsche Bank AG is a multinational bank headquartered in Germany and is the 17thlargest bank in the world.[12]It provides banking services for both private and corporate parties. On top of its banking services, Deutsche engages in active and passive fund management with 700 billion EUR in assets under management.[13]The Australian branch of Deutsche is one of its four major hubs in the Asia Pacific region and prioritises its corporate clientele.[14]

Citigroup

Citigroup is a global investment bank centred in the United States. It is the 4thlargest bank in the U.S. and 16thglobally with $1.8 trillion total assets.[15]Citi is divided into two subsidiaries, Citicorp and Citi Holdings. Citicorp is responsible for its retail and corporate banking services while Citi Holdings represents its asset management division. The Australian branch of Citi offers both retail and corporate banking services.[16]

Background

Financial System Inquiry

In November 2014, a Committee appointed by Australia’s Treasurer published the Financial System Inquiry (FSI).[17]Previous financial system inquiries, such as the “Campbell Report” and the “Wallis Report,” were the catalysts for major economic reforms.[18]The FSI examines the state of the Australian financial system and produces recommendations which are pertinent to the underpinnings of the financial sector. The report emphasized the need for banking resiliency and the banks responded. The FSI instigated an effort by the major banks to raise additional capital from its investors. This capital raising was the genesis of the criminal cartel case. The critical recommendations which engendered the banks’ response relates to capital levels, leverage ratio, and mortgage risk weights.[19]

- Unquestionably strong capital levels

The FSI indicates that capital levels for the Registered Deposit-taking Institutions (ADI) in Australia should be “unquestionably strong.”[20]The term “unquestionably strong” is defined as a level which mirrors the highest quartile of internationally active banks. The Australia Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) in its information report concerning international capital comparison clarifies that the fourth quartile is the minimumthreshold of compliance and that an “unquestionably strong” standard may exceed the fourth quartile.[21]

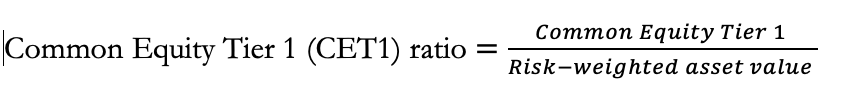

The FSI’s definition of “capital levels” is a reference to Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) which is recognised internationally by the Basel Accords, a global regulatory financial framework.[22]CET1 is comprised of shareholders’ common equity and acts as a primary defence against insolvency and bank failure.[23]CET1 is subordinated to all other elements of funding as it is the first to absorb loss if it occurs. The aggregate number for CET1 is less relevant than the ratio. The ratio measures a bank’s solvency and capital strength and the formula is as follows:

At the time of publication of the FSI in 2014, the CET1 ratio of the Australian major banks comparatively averaged in the third quartile of internationally active banks.[24]

- Introduction of a leverage ratio

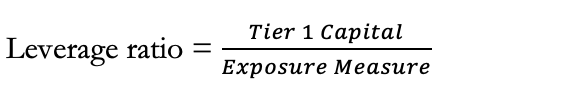

The FSI proposes the introduction of a requisite banking leverage ratio which alludes to Australia’s intention to comply with the international standards set in the Basel framework.[25]The nominated leverage ratio measures the ADIs’ resistance to financial shock. Empirical evidence highlights the elevated levels of risk associated with improper leverage.[26]The inquiry advocates for a departure from the risk-weighted approach in setting the leverage floor. The formula for the leverage ratio is as follows:

Tier 1 capital represents CET1 in addition to other instruments which can be converted into equity easily. Exposure measure is defined by the APRA as the sum of on-balance sheet exposure, exposures to non-market-related on-balance sheet items, derivative exposures, and securities and financing exposures.[27]

The minimum requirement for the leverage ratio is projected to be at 4%.[28]The introduction of a minimum leverage ratio requires banks to re-examine the adequacy of its tier 1 capital and exposure.

- Narrow mortgage risk weight differences

The ratios pertaining to capital levels are adjusted for risk. There is a disconnect between the risk-adjusting process of standard ADIs and Accredited ADIs (IRB banks).[29]ANZ is among one of the five IRB banks operating in Australia that utilise an internalised risk-adjusted system. Risk is evaluated by attributing weighting to various asset markets. The standard ADI adjustment weighs mortgages at 39% while the IRB adjustments attribute only 18% to mortgages.[30]The objective is therefore to close the distance between how banks evaluate risk, with the target for the new IRB mortgage risk rate at 25%.[31]

The practical impact of narrowing the mortgage weights is that IRB banks are required to raise their capital levels to maintain the same ratio.

ANZ’s Response

On the 6thof August 2015, in light of the publication of the Financial System Inquiry, ANZ announced its intention to raise new capital through the sale of ordinary shares. This approach copied the National Australia Bank’s, another member of the “big four,” to bolster its own capital levels.[32]ANZ endeavoured to raise $2.5 billion from its institutional investors and $500 million from retail investors.[33]The minimum price at which investors would pay per share was at $30.95.[34]

Prior to the announcement of the issuance of new shares, ANZ contracted with Deutsche Bank, Citigroup and JP Morgan Australia.[35]An agreement was reached in which the investment banks would fully underwrite the $2.5 billion worth of shares offered to institutional investors. Unfortunately, ANZ overestimated the demand and one third of the shares were not sold.[36]As a consequence of the underwriting agreement, 31% of the shares were acquired by the underwriters.

Allegations and Aftermath

Allegations

In June 2018, the ACCC charged ANZ, Deutsche Bank and Citigroup with criminal cartel offences following a two-year investigation.[37]Those who were accused held senior positions within each of their banks respectively. They are as follows[38]:

- Rick Moscati – Former ANZ treasurer

- Stephen Roberts – Former head of Citi Australia

- John McLean – Head of capital markets for Citi Australia

- Italy Tuchman – Former head of markets for Citi Australia

- Michael Ormaechea – Former CEO of Deutsche Bank Australia

- Michael Richardson – Former head of markets for Deutsche Bank Australia

JP Morgan and its executives were not charged despite participating in the underwriting process due to an alleged immunity deal.[39]The Director of Public Prosecutions, on behalf of the ACCC, has discretion to grant immunity for criminal offences.[40]Those who are given immunity must be “the first person to apply for immunity in respect of the cartel” which is similar to other forms of whistle-blower immunity policies.[41]

The accused banks promised to vigorously defend the charges against its senior members.[42]The initial court hearing of first instance will be on the 5thof February 2019, the result of the criminal cartel case is therefore pending.[43]Consequently, there is a paucity of information surrounding the exact action of the accused as details could prejudice the jury.

On the 6thof August 2015, ANZ announced the placement of A$3 billion fully paid ordinary shares through its Share Purchase Plan which was divided into A$2.5 billion for institutional investors and A$500 million for retail investors.[44] The placement was fully underwritten by Citi, Deutsche, and JP Morgan. If the totality of the shares were not sold, the underwriting agreement obliged the underwriters to acquire the shortfall. The eventual shortfall amounted to 31% of the placement with institutional investors, valued at A$789 million, which was not disclosed by ANZ nor the underwriters.[45]The approved disclosure statement announced that ANZ had “raised $2.5 billion in new equity” without mentioning the shortfall.[46]

The ACCC has yet to reveal its submission against the banks given the unresolved status of the case. However, it is not impossible to surmise the potential argument against the banks. The ACCC’s case reportedly focuses on how the underwriters distributed the shortfall, [47]specifically whether there was an “understanding” between ANZ and the underwriters on the allocation of the excess shares.[48]The prosecutor would contend that ANZ knowingly worked in concert with underwriters to manipulate the price of ANZ shares. This would have been done by intentionally overestimating the demand for its shares and subsequently reaching an agreement with the underwriters about the distribution of the shortfall. By withholding or through tactical assignment of the eventual shortfall, ANZ would theoretically be able to restrict the available shares in the market and artificially inflate the share price. A pertinent question to ask is therefore: Is it plausible for one of the largest banks, advised by well-researched underwriters, to overestimate the demand for its shares in its domestic market by 31%?

Cartel activity is defined in Australian competition law.[49]It primarily includes conduct relating to:

- price-fixing

- restricting outputs in the production and supply chain

- allocating customer or suppliers

- bid-rigging.

If the banks reached an agreement, implicit or explicit, concerning how the shortfall would be distributed, the offence committed pertains to a restriction of output. Intentional output restrictions “substantively lessen” competition in Australia which is a punishable cartel offence.[50]However, the output restriction offence is typically endemic to goods and services.[51]The ACCC’s past case against Tasmanian Atlantic, in which the supply of salmon was culled, highlights the nature of the offence. A stock of salmon perhaps differs from the stocks of ANZ. Whether ordinary shares in a company qualifies as either a good or service for the purposes of the cartel offence is yet to be determined by the courts. The qualities which constitute a good or service is not immediately obvious, which is exemplified by the discussions on digital goods in both Australia[52]and around the world.[53]Hence, the claim brought against the banks will likely contain previously unaddressed and novel submissions. It is ultimately impossible to discern the extent to which competition law was breached before the conclusion of the case in February 2019.

Consequences

The potential sanctions for criminal cartel activity differs from civil proceedings. ACCC’s maximum pecuniary penalty for civil cartel activity is $10 million per act or omission for corporations and greater for criminal offences.[54]Individuals who commit civil cartel offences are fined up to $500,000 per offence whereas the criminal penalty ceiling is up to $420,000. Although the pecuniary penalties are similar, criminal cartel offences carry the added penalty of time in jail. The ACCC may allocate a maximum of 10 years for each convicted offender. Due to the disparity of punishment, criminal cases are understandably more difficult to prove. Civil cases require ACCC to prove an offender’s culpability “on the balance of probabilities,” namely with a probability of over 50%. Criminal proof requires the “beyond reasonable doubt” standard, which is a much higher threshold.[55]Criminal action is brought by the ACCC solely for “serious cartel conduct.”[56]

Since June 2018, in the wake of the announcement by the ACCC of the criminal case against it, ANZ’s share price dropped 6.97% (from $26.66 to $24.80). This is an empirical exhibit of bounded rationality.[57]Bounded rationality underlines a person’s limited cognitive abilities. A fully rational person cannot exist as the ambit of their rationality is closely affixed to their limited knowledge. It would therefore be unsurprising for an investor to have a skewed willingness to buy and sell ANZ shares after news of its criminal charges. The decline in the share price is a depiction of a loss of confidence which uncovers the truth that the ramifications of unethical practice can exist outside of the courtroom.

Ethics Discussion

Deontology: Rules and regulation

An important ethical position in finance is deontological. The premise of deontological ethics is that one’s conduct must conform to a series of inviolable rules. Those rules exist in the modern world as laws and regulations which govern business conduct. The absolute moral position is, therefore, the one in which the laws are followed. In theory, the rules ought to be perfect. To that effect, Kant claimed that “a conflict of duties is inconceivable” which suggests all eventualities must have been within the contemplation of the lawmakers.[58]However, reality is characterised by imperfection.

Regulation cannot address every possibility of human behaviour and modern laws cannot be infallible.[59]It is clearly depicted in the present criminal cartel case. Whether the accused banks contravened the law is currently in dispute. Citi comments that “underwriting syndicates… have operated successfully in Australia in this manner for decades.”[60]The case therefore introduces a new ethical question: In instances where no legal guidelines are present, how should a business entity operate? It is to the advantage of the law that the rules governing finance are interpreted textually. A textualistic approach safeguards the clarity and certainty of the law. Yet, ethics, unlike the law, ought to be discernible. The accused parties potentially breached duties of which they were unaware. Although it is no excuse to insinuate they were ignorant of the laws, it is a plausible ethical explanation to suggest the laws were insufficiently clear in instituting the boundaries of conduct. Thus, the ethics of the banks’ conduct should not be determined solely on deontological thought.

Virtue: A Company of Characters

If deontological ethics is insufficient to determine whether the banks’ conduct was ethical, virtue ethics is an appropriate solution. Virtue ethics emphasises the importance of developing good habits of character, focusing on motivations of moral behaviour.[61]Aristotle’s concept of eudaimonia underpins the theory regarding virtue ethics.[62]The concept may be divided into four basic attributes:[63]

- Virtuous character

Ethical conduct which is virtuous focuses on an “internal” good. It can be described as characteristics which are morally good such as kindness, generosity or wisdom. This is contrasted with “external” goods such as property or possession.[64]Although banks are business entities, it is possible to apply the internal virtue test independently. The test is whether the conduct of the accused bankers was completed for the purposes of an internal pursuit. The accused bankers did not disclose the shortfall nor their agreement of how the excess shares would be distributed. Their actions are evidently formulated for the pursuit of external and pecuniary means, which is contrary to a virtuous character.

- Community

Firms and organisations are at the heart of the community. The role of the firm is to create an infrastructure which nurtures ethical practice. The role of an organisation should be active rather than passive.[65]Banks should not promote subterfuge and secrecy. In the present case, the bankers actively damaged the reputation of banking which is an organisational structure at the center of a greater community.

- Moral Judgment

The concept of moral judgment argues against deontological ethics. This facet of virtue ethics rejects rule-based moral philosophy. MacIntyre posits that in the pursuit of ethical excellence, one should “exhibit a freedom to violate the present established maxims.”[66]This does not insinuate that banks ought to ignore rules and regulations, it suggests that laws are a foundation for ethical conduct which may be contravened for the purposes of moral excellence. ANZ and its underwriters contravened this principle as their potential violation of competition law is driven by the desire of pecuniary interests rather than moral excellence.

- Moral exemplars

Virtue ethics emphasises the importance of suitable moral examples. The emulation of ethical conduct is a necessity for professionals as a role model is at times more intuitive than a set of rules.[67]Banking professionals should therefore model their behaviour after other accomplished professionals. However, the controversy generated by the potential cartel conduct contradicts the image of an ethical exemplar. The case is particularly damning due to the status of ANZ as one of Australia’s premiere banking institutions. The decisions of the bankers should be theoretically lauded as the pinnacle of ethical behaviour, not publicly disparaged. Ethical conduct ought to be emulated, yet the banks’ actions leave much to be desired.

Although virtue ethics is predominantly applied on an individualistic level, the framework could be extended to produce a broad ethical guideline for organisational entities. Consequently, the banks’ conduct proves to be below the ethical threshold required by virtue ethics.

Utilitarianism: Ends Justifying Means

If it is accepted that laws cannot encompass all possible eventualities, then it follows that a person or company may at one point be in an unprecedented ethical position. The utilitarian approach may supplement virtue ethics in uncovering the correct moral action if such a position is reached.

Utilitarianism is a consequentialist approach to ethics in which conduct is evaluated by the total amount of “good” or “utility” generated.[68]The potential application of utilitarian principles is not unique to finance. In the field of medicine, utilitarian tenets are often contemplated.[69]Physicians are at times tasked with the decision to treat one person or group over another due to a scarcity of time or resources. An ethical utilitarian decision would examine the possible stakeholders affected by the physician’s decision to treat one patient over another. Similarly, the conduct of ANZ and its underwriters should be scrutinised by its impact on the affected stakeholders.

- Investors and shareholders

Investors are the first to be affected by the decisions of banking institutions. One of the functions of ANZ’s agreement was to preserve or inflate the price of its shares. However, it had an opposite effect. The value of ANZ shares declined steeply after news of the criminal cartel case.[70]The monetary loss depicts a loss of investor confidence. ANZ owed a fiduciary duty to continuously disclose any information which would be pertinent to market participants that would otherwise be generally unavailable.[71]The undisclosed shortfall in conjunction with the underwriting agreement further damages the goodwill of the bank. The result for investors and shareholders is a loss of money and trust.

- Customers and the public

As a deposit-taking institution, ANZ’s customers are also its creditors. 60% of Australian banks’ funding is from domestic household and business deposits.[72]Adverse effects on its customer base therefore affects its profits and functionality. Potentially unethical conduct fosters mistrust among the banks’ customers. The financial services industry is perceived to be one of the least ethical industries.[73]Action which generates mistrust perpetuates this notion. A lack of trust in the banking system may lead to greater macroeconomic concerns in the long-run such as recession or bank failure.[74]The public would be the ultimate recipient of the consequences of an accentuated macroeconomic risk. As such, the actions of ANZ and its underwriters foster mistrust in the banking system which, in the long-run, exposes the public to an elevated level of financial risk.

The adverse effects observed by the stakeholders of ANZ’s conduct illustrates a contradiction to utilitarian ethics. ANZ’s decision did not distribute the greatest amount of utility nor the greatest amount of good.

Conclusion

ANZ, Deutsche Bank, and Citi are faced with criminal cartel charges. The result of ACCC’s claim against these banks is pending trial in February 2019. Although rules-based ethics is the common school of thought in finance, it is insufficient in covering this case in its entirety. Under the lens of the major normative ethical approaches, the banks operated unethically as management did not exibit virtuous behaviour and the banks neglected to consider effects on stakeholders and the wider community.

Editor: Eric Witmer

Endnotes

[1]Australian Competition and Consumer Commission. “About the ACCC.” Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, 2018, https://www.accc.gov.au/about-us/australian-competition-consumer-commission/about-the-accc.

[2]Competition and Consumer Act 2010, s 6A(1).

[3]Australian Competition and Consumer Commission. ACCC & AER Annual Report 2017-18, Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, 2018. https://www.accc.gov.au/publications/accc-aer-annual-report/accc-aer-annual-report-2017-18.

[4]Australian Competition and Consumer Commission. 2018 ACC Compliance and Enforcement Policy and Priorities, Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, 2018. https://www.accc.gov.au/publications/compliance-and-enforcement-policy.

[5]Australian Competition and Consumer Commission. ACCC & AER Annual Report 2017-18, Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, 2018. https://www.accc.gov.au/publications/accc-aer-annual-report/accc-aer-annual-report-2017-18.

[6]Ibid.

[7]“ASX 200 List of Companies.” ASX 200 List, 2018, https://www.asx200list.com.

[8]Ibid.

[9] “Annual Report/Annual Review” ANZ personal banking, 2018, https://shareholder.anz.com/annual-report-annual-review.

[10]Guadalquiver, J. “Mitigating TBTF: The Australian Four Pillars Policy.” Seven Pillars Institute, 2016, https://sevenpillarsinstitute.org/mitigating-tbtf-australian-four-pillars-policy/

[11]“ASX 200 List of Companies.” ASX 200 List, 2018, https://www.asx200list.com.

[12]“Top 100 banks in the word” Banks around the world, 2 April 2018, https://www.relbanks.com/worlds-top-banks/assets.

[13] “DWS” Deutsche Bank, 27 March 2018, https://www.db.com/company/en/dws.htm.

[14]“Deutsche Bank in Australia

Deutsche Bank,2018, https://www.deutschebank.com.au/australia/index.html.

[15]“Top 100 banks in the word” Banks around the world, 2 April 2018, https://www.relbanks.com/worlds-top-banks/assets.

[16]“Our business” Citi Australia, 2018, https://www.citi.com/australia/ourbusiness.html.

[17]“Final Report” Financial System Inquiry, 2014, http://fsi.gov.au/publications/final-report/.

[18]“Financial System Inquiry”Financial System Inquiry, 2014, http://fsi.gov.au/.

[19]Eyers, J. “ANZ to be hit with criminal cartel charges” Australian Financial Review, 2018, https://www.afr.com/business/banking-and-finance/anz-hit-with-criminal-cartel-charges-20180601-h10tpv.

[20] “Final Report” Financial System Inquiry, 2014, http://fsi.gov.au/publications/final-report/. At (xviii)

[21]APRA. International Capital Comparison. 2015, https://www.apra.gov.au/information-papers-released-apra. At page 24.

[22]“Basel III: a global regulatory framework for more resilient banks and banking systems” Banking for international settlements, 2011. https://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs189.htm.

[23]“Final Report” Financial System Inquiry, 2014, http://fsi.gov.au/publications/final-report/. At page 40.

[24]APRA. International Capital Comparison. 2015, https://www.apra.gov.au/information-papers-released-apra. At page 21.

[25]“Final Report” Financial System Inquiry, 2014, http://fsi.gov.au/publications/final-report/. At page 84.

[26]IMF. Taxation, Bank Leverage, and Financial Crisis. 2013. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/31/Taxation-Bank-Leverage-and-Financial-Crises-40341.

[27]APRA. Leverage ratio requirements for ADIs. 2018. https://www.apra.gov.au/file/10871.

[28]Ibid

[29]“Final Report” Financial System Inquiry, 2014, http://fsi.gov.au/publications/final-report/. At page 60.

[30]Ibid at 61.

[31]“APRA reaffirms revised mortgage risk weight target.” Australian Prudential Regulation Authority, 2016. https://www.apra.gov.au/media-centre/media-releases/apra-reaffirms-revised-mortgage-risk-weight-target.

[32]“NAB posts profit of $3.4b, raises $5.5b in extra capital.” Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 2015, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-05-07/nab-posts-profit-growth-raises-capital/6451200.

[33]“ANZ to raise $3 billion from shareholders to increase capital levels.” Sydney Morning Herald, 2015,https://www.smh.com.au/business/banking-and-finance/anz-to-raise-3-billion-from-shareholders-to-increase-capital-levels-20150806-gismo0.html.

[34]Ibid.

[35]“Concise Statement” Australian Securities and Investments Commission, 2018, https://asic.gov.au/about-asic/news-centre/find-a-media-release/2018-releases/18-268mr-asic-commences-civil-penalty-proceedings-against-anz-for-alleged-continuous-disclosure-breach-in-relation-to-2015-institutional-equity-placement/.

[36]“ANZ cartel case: What is underwriting and why is it key for share markets?” Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 2018, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-06-06/anz-underwritten-share-sale-gone-wrong-why/9839728.

[37]“Criminal cartel charges laid against ANZ, Citigroup and Deutsche Bank.” Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, 2018. https://www.accc.gov.au/media-release/criminal-cartel-charges-laid-against-anz-citigroup-and-deutsche-bank.

[38]“Citigroup, Deutsche Bank face Australian court in landmark cartel case.” Reuters, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-australia-banks-cartel/citigroup-deutsche-bank-face-australian-court-in-landmark-cartel-case-idUSKCN1MJ0B4.

[39]Durkin, Eyers, Shapiro. “ANZ, Deutsche and Citigroup face criminal cartel charges.” Australian Financial Review, 2018, https://www.afr.com/business/banking-and-finance/jpmorgan-granted-immunity-in-anz-cartel-case-20180601-h10u5a

[40]“ACCC immunity and cooperation policy for cartel conduct” Australian Competition and Consumer Commission,2014, https://www.accc.gov.au/publications/accc-immunity-cooperation-policy-for-cartel-conduct.

[41]Ibid at page 4.

[42] “ANZ cartel case: What is underwriting and why is it key for share markets?” Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 2018, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-06-06/anz-underwritten-share-sale-gone-wrong-why/9839728.

[43]“Current Australian Competition Cases.” Australian Competition Law, 2018. https://www.australiancompetitionlaw.org/casescurrent.html.

[44]“Concise Statement” Australian Securities and Investments Commission, 2018, https://asic.gov.au/about-asic/news-centre/find-a-media-release/2018-releases/18-268mr-asic-commences-civil-penalty-proceedings-against-anz-for-alleged-continuous-disclosure-breach-in-relation-to-2015-institutional-equity-placement/.

[45]Ibid at page 2.

[46]“ANZ completes $2.5 billion Institutional Equity Placement.” ANZ, 2015, https://media.anz.com/posts/2015/08/anz-completes–2-5-billion-institutional-equity-placement.

[47]Thomson, J. “Capital raising shortfall at the heart of ANZ’s cartel case.” Australian Financial Review, 2018, https://www.afr.com/brand/chanticleer/capital-raising-shortfall-at-heart-of-anzs-cartel-case-20180601-h10txl.

[48] Durkin, P. “Video conference call at the heart of criminal cartel case against ANZ.”Australian Financial Review, 2018, https://www.afr.com/business/banking-and-finance/video-conference-call-at-heart-of-criminal-cartel-case-against-anz-20180603-h10war.

[49]Competition and Consumer Act 2010, s45.

[50]Ibid.

[51]“Output Restrictions.” Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, 2018, https://www.accc.gov.au/business/anti-competitive-behaviour/cartels/output-restrictions.

[52]“Applying GST to digital products and services imported by consumers.” Parliament of Australia, 2015, https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/BudgetReview201516/Digital.

[53]Green, S. Saidov, D. “Software as Goods.” 2007, http://www.cisg.law.pace.edu/cisg/biblio/green-saidov.html.

[54]“Fines and penalties.” Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, 2018, https://www.accc.gov.au/business/business-rights-protections/fines-penalties.

[55]“Burden of proof.” Australian Law Reform Commission, 2018, https://www.alrc.gov.au/publications/9-burden-proof-0.

[56]“Cartels.” Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, 2018, https://www.accc.gov.au/business/anti-competitive-behaviour/cartels#accc-referral-of-matters-for-possible-criminal-prosecution.

[57]Selten, R. “What is bounded rationality?” 1999.

[58]Kant, I. The Metaphysical Elements of Ethics. 1780.

[59]Kofman. Payne.A Matter of Trust. Melbourne University Press, 2017.

[60]“ANZ cartel case: What is underwriting and why is it key for share markets?” Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 2018, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-06-06/anz-underwritten-share-sale-gone-wrong-why/9839728.

[61]Fieser, J. “Ethics.” Internet encyclopedia of philosophy, 2018, https://www.iep.utm.edu/ethics/.

[62]Dobson, J. “Applying virtue ethics to business: The agent-based approach.” 2007, http://ejbo.jyu.fi/articles/0901_3.html.

[63]Ibid.

[64]MacInytre, A. After Virtue: A study in Moral Theory, 1981. Chapter 14.

[65]Dobson, J. “Applying virtue ethics to business: The agent-based approach.” 2007, http://ejbo.jyu.fi/articles/0901_3.html.

[66]MacInytre, A. After Virtue: A study in Moral Theory, 1981.

[67]Hintzman, D. Ludlam, G. Differential forgetting of prototypes and old instances: Simulation by an exemplar-based classification model. 1980.

[68]“History of Utilitarianism.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2014, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/utilitarianism-history/.

[69]Mack, P. Utilitarian Ethics in Healthcare. International Journal of the Computer, The Internet and Management Vol. 12, 2004.

[70]“Australian and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (ANZ) – Share price information” ASX, 2019, https://www.asx.com.au/asx/share-price-research/company/ANZ.

[71]Corporations Act 2001, s674.

[72]Munchenberg, S. “Banks have to balance interests of all stakeholders.” Australian Financial Review, 2016, https://www.afr.com/business/banking-and-finance/banks-have-to-balance-interests-of-all-stakeholders-20160804-gqkxti.

[73]“Health professionals continue domination with Nurses most highly regarded again; followed by doctors and pharmacists.” Roy Morgan, 2017. http://www.roymorgan.com/findings/7244-roy-morgan-image-of-professions-may-2017-201706051543.

[74] Redwood, J. “Could loss of confidence in the banks tip into a recession?” https://www.ft.com/content/4fe4726e-d3d0-11e5-829b-8564e7528e54.