Income Inequality and Its Effect on Political Inequality

The third in SPI’s series on Inequality

By: Remy Smith

Political races are expensive. Candidates are pressed by consultants and campaign management to raise exorbitant amounts of money to create lit pieces and other advertisements that may sway potential voters. Recently, the advent of SuperPACs allows large donors to circumvent campaign contributions.

Though limited in direct contributions to a campaign (so called hard money), any individual can donate unlimited sums to a SuperPAC or soft money. The latter is used for issue advocacy or support of a candidate. SuperPACs are controversial because they allow a few wealthy citizens to dominate political outcomes by filling a candidate’s SuperPAC with large amounts of money. Some argue SuperPACs are a major cause of inequality in America’s political system. A small percentage of Americans control vast sums of funds and they now have a disproportionate degree of political influence. Is this political inequality permissible and does it pose a threat to the political system?

The Importance of Opportunity

Political inequality is, in many ways, akin to economic inequality. Both appear to be growing problems in the US and their solutions require some level of equal opportunity. Inequality of outcome is justified and even beneficial to any system as it incentivizes hard work and rewards individuals based on merit. Inequality of opportunity, in contrast, is not only unjust but also perilous.

Opportunity is arguably a right. Everyone deserves a chance to succeed and none should be denied opportunity. Polls suggest a majority of Americans support the idea of equality of opportunity. The concept of equality of opportunity is may be applied to political inequality.

Virtues of Equality of Political Opportunity

Democracy relies on and is defined by equal political opportunity. It is a basic principle of democracy that citizens who meet rudimentary requirements (like age and national birth) are able to run for elected office. This implies a fundamental equality in democracy: the equality of opportunity to declare candidacy for an elected position.

When all members of society can run for office, it increases representation from all segments of society, from farmers to industrial workers to financiers. A community leader from a minority group will not be barred from candidacy for, say, not owning property or for belonging to a certain racial group. This notion runs is true from municipal level to the federal level. People have a say in governance through the election of those who best serve the their interests.

Ability to Run for Office

Prior to the Progressive Era, the U.S. had a system that restricted candidacy for political office. The U.S. Senate, instead of being elected by the people, comprised of individuals selected by state senates. America’s founders intended such a system because they wanted to restrict the power of the people (Jefferson and others feared the tyranny of the masses), but it resulted in a congressional body that did not serve the will of citizens and thus faced no accountability to the people.

Not everyone had an equal chance to become senator. In this early America, being born to a poor family who did not own land, or to an ethnic minority meant the individual would not have the connections or power to be elected by a state senate. It was a select few who were wealthy enough to attend high school or college and could become involved in matters of state that were most likely to be elected. That system closed off equal opportunity.

Importance of the Vote

The most common means by which inequality of political opportunity occurs is through voter suppression or limiting the electorate. Voting is inherently equalizing. A citizen has one vote to cast for the candidate she believes will best represent and better her interest. One person, one vote – completely equal. When this principle is corrupted voices are silenced and political inequality results.

Returning to the early-American example, it is obvious how the voices of certain groups were stifled: there were significant impediments voting. Preventing certain segments of society from voting largely prevented the interests of the poor and the working class from being pursued in government. This neglect contributed to many Americans working in dire conditions. Few elected officials found it in their self-interest to go against business and property owners i.e., voters, in favor of policies that favored Americans without significant political heft. It took a populist movement and dedicated reformers to change American politics to favor, or at least be receptive to labor. Voter suppression is clearly a force that drives inequality.

Virtues of Political Inequality

Political inequality is not necessarily detrimental. On the contrary, some elements of political inequality are necessary for a well-structured and incentivized political system. Much like economic outcomes, inequality in result is justifiable. Those who actively engage in the political system and seek to shape political outcomes rightfully have a louder voice in politics.

There are many ways to be politically engaged and doing so is necessary to be heard: “equal consideration of the preferences and needs of all citizens is fostered by equal political activity among citizens” (Sidney Verba). To influence policymakers, voters can, for instance, work on campaigns, contact congress members, participate in protests, and vote.

Studies find that policymakers are overwhelmingly responsive to the whims and wants of the highest income earners. Naturally, many people are offended by this reality. Is it really an equal democracy when the will of the majority is disregarded? Yet, democracy reflects those who engage in the democratic process. Political inequality, if a result of unequal engagement, is beneficial to the system and offers justifiable reason for the more influential will of the affluent.

Engagement

Politicians, while swayed by money, also are responsive to those who seek to influence political outcomes. A recent study done by Page, Bartels and Seawright finds that the views of American politicians are increasingly reflective of those of the affluent. This is partly because of substantial campaign donations, but it is also due to the political engagement of wealthy voters. Politicians respond to those who are engaged.

In 1990, nearly 50% of the top quintile income earners contacted a congress member versus 25% of the poor. The study by Bartels et al finds that 47% of the wealthy made “at least one contact with a congressional office”, 40% contacted their own senator, 37% their own House member, and “about one quarter contacted a representative or senator from another district or state”. The wealthy are not afraid to take to the streets either. Protests, “which demand little in the way of skills or money and which is often thought of as ‘the weapon of the weak’” (Schlozman et al), are also dominated by the wealthy. The 1990 survey finds more than twice as many of those from the top income quintile than the bottom quintile engage in protests. While working on campaigns, contacting political officials, and protesting do not necessarily influence policy outcomes, they are an opportunity to aid the campaign of sympathetic politicians and to make one’s voice heard.

The Importance of the Vote, Part 2

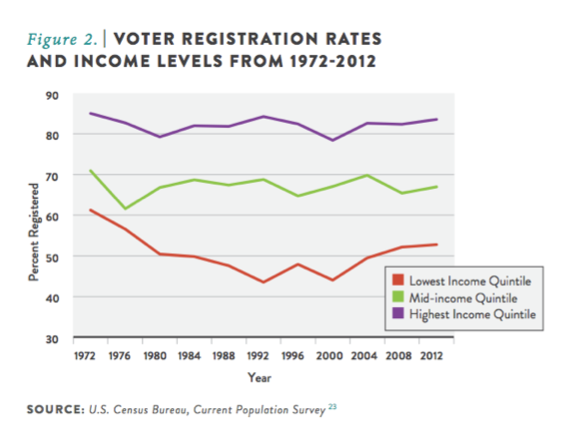

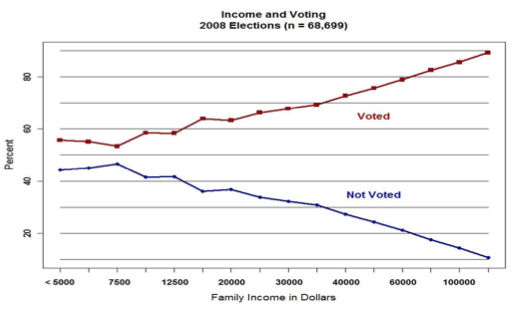

Perhaps the easiest and most effective way to exert political opinion is to vote. Voting, the basic tenet of a democracy, holds elected officials accountable to the public. But for many, the right to vote is wasted. The two graphs below depict an alarming trend in American politics: the discrepancy of voter registration and turnout between the affluent and the poor.

Source: voteview.com

The first graph demonstrates the lower voter registration of those in the lowest income quintile. For the majority of the years covered by the survey, voter registration was below 50% for the lowest quintile and it rose in the first Obama campaign to get out the minority vote. As income increases, so does the percentage of those who register to vote. The second graph is for the 2008 election and shows the increase in actual voting as income rises. For families earning less than $50,000, which was about the median family income in 2008, only between 50 and 75% voted – worrying especially considering this was a presidential election and the Obama campaign’s focus on bringing minority voters to the polls. Of note: 99% of the wealthiest Americans (the test group had a median wealth of $7.5 million) surveyed by Page, Bartels, and Seawright voted in the 2008 election.

Why do large numbers of low- and medium-income voting-age citizens neglect to vote? One explanation is lack of time. Low-income Americans often find themselves working multiple jobs to make ends meet and therefore may not have time to make it to the polls. An easy solution to this would be to make Election Day a national holiday so no voter has to compromise work in order to vote. Another theory is that low- and medium-income voters find political outcomes, both in elections and policy, so skewed to the will of the affluent they do not find it worthwhile to vote. This of course creates a perpetual cycle whereby outcomes will be even more dependent upon the desires of the wealthy and other voters will be even more disincentivized to vote. A new trend emerging in conservative states is also damaging voter turnout. Voter ID laws and the limitation of absentee voting in some states negatively impacts turnout for poor and minority voters. Often seen as racially motivated, this move is thought to be designed to keep the Republican Party in power in state legislatures because the new requirements make it more difficult for some segments of the population to vote.

Influence of the Politically Active

It is no wonder wealthy Americans have a strong say in policy outcome – they vote presumably, for candidates who best represent their interests. Benjamin Page and Martin Gilens, in a new study called “Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens”, find that “it makes very little difference [in policy] what the general public thinks.” Such results are caused by inequality in political activity. In this way, the potential for unequal outcomes incentivizes political engagement and, at the least, awareness in order to assure responsive governance.

The Role of Money

One of the most divisive issues in campaign finance and in the theory of equality of political opportunity is the role of money. Opponents of hard, soft, and shadow money contend the ability to contribute unlimited sums has a corrupting effect on politicians. Proponents of unlimited financial contributions argue political funding is a provision of the freedom of speech: a person makes a political statement when donating money to a campaign or to an organization supporting a certain candidate.

Whatever the case, unlimited campaign contributions, in the form of hard, soft, or shadow money, create inequality of political opportunity. Those who are well positioned in the economic hierarchy immediately have a resource advantage versus those who are poorly placed.

Three Categories of Political Activity

We can divide political activity into three categories:

(1) Voting

(2) Political engagement

(3) Monetary donations

Categories (1) and (2) are necessarily equal in that everyone has one vote and everyone has the ability to volunteer in a campaign. Money, however, is a not an equalizer. Assuming unlimited contributions, there is no initial equality. Take this example: there are two voting citizens, Rob and Joe, both of whom vote in every election and volunteer on the campaign of their favorite candidates (who happen to be competing). Rob has an income of $200,000 a year with a large savings account and is willing to donate a substantial portion of this year’s income to candidate R. Joe, on the other hand, only makes $30,000 a year and needs to save all that he can in order to put his son through college and thus cannot contribute as much as he would like. That is not equality of opportunity. Rob’s opportunity is 6 times that of Joe’s because of his income and, taking account Joe’s need to save, Rob’s opportunity is even higher. Even if each person were limited to contributing 15% of total income, Rob’s opportunity to sway political outcomes is much higher than Joe’s. The problem with campaign contributions is a person’s financial success determines his ability to alter political outcomes.

Willingness and Ability

With monetary contributions, there are two variables affecting equality: willingness and ability to donate. Categories (1) and (2) are limited to the sole variable of willingness. In contrast, not everyone has the equal ability to donate. Unlimited campaign contributions prohibit true equality of opportunity. There are some who argue political engagement is also subject to the variable of ability – in this case, the ability to allocate time to political engagement. This argument has merits. After all, retirees and the affluent can afford to spend more time volunteering on campaigns. However, with the advent of the internet and social media, it is a quick and easy process to be politically engaged. Volunteering can be done remotely in the form of phone banking which can be done remotely at any reasonable time. With candidate and office-holder websites, it is relatively easy and takes minutes to write a message to a politician. The same applies for Facebook and Twitter. Statuses or tweets explaining one’s support of a candidate are simple and easy ways to voice support. These technological advances have helped in reducing the use of time for political engagement.

Campaign Contributions

To assure true equality in the ability to donate, contributions must be limited to a level equal to the lowest amount voters are willing to give, a number that almost certainly will be $0. Eliminating campaign contributions restricts freedom of speech, necessarily limiting one’s ability to impact political outcomes. It seems equality of opportunity and justifiable unequal outcomes cannot be attained at the same time.

Perfect equality is perhaps unattainable, but we cannot cease trying to create equality in the political system. A contribution limit should be enacted and soft and shadow money banned as they create overwhelming inequality of opportunity. The new limit may be based on any number of factors. One possible means by which the limit is determined is to use the average of the median contribution across a variety of contests. Another way is to survey a consortium of voters who reflect the demographics of active voters and use the median of their willingness to donate as the contribution limit. Some public money should also be made available to all candidates and parties that achieve a certain threshold in the previous election.

There are many benefits to imposing a limit on campaign contributions besides equality of opportunity. One other benefit is a political candidate will tend to court more voters. Limiting campaign contributions has a populist effect.

Equality of political opportunity is a basic tenet of democracy. It allows for all citizens to have equal potential to sway political outcomes though the actual effect on political outcomes will vary based on political activity. The introduction of money into the political system opens the possibility of destroying the equality of political opportunity. A limit in political contributions can actually have a populist effect because politicians need to reach and appeal to more people in order to raise necessary funds.

However, failing to ban soft and shadow money and establishing more stringent regulations on hard money can have a very negative effect on the political system. The continuation of SuperPACs and the infiltration of money into America’s democracy have adverse effects. An extrapolation of Benjamin Page’s study points to the U.S. slowly evolving into an oligarchy. The continuation of increasing money into the political system leads to barriers to entry in political activity, either through dollars needed to have a voice heard or through the election of officials acting in accord to the will of the wealthy. These elected officials may enact legislation that further obstructs political engagement. This facet of politics is evident in some states where barriers to voting already have been erected. The effects of not limiting money in politics could be dire.

Editor: Dr. Kara Tan Bhala