Wells Fargo Fake Accounts Scandal

By: Harley Comrie

Republicans in Congress and Donald Trump want to roll back Dodd-Frank regulations to help banks become more profitable, and remove ‘burdensome’ regulations. These politicians apparently forget that so-called ‘light touch regulation’ was a reason for the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008, the effects of which haunt us still and carried President Trump to power. It is helpful to remember even after the GFC, bank scandals recur with dismal regularity and that regulations form the thin red line protecting consumers from the greed of financial institutions.

The following is a description and an evaluation of the continuing multi-faceted scandal featuring Wells Fargo & Company. Revelations about the behavior of bank employees and executives are ongoing.

Parties Involved

The main parties involved in the scandal are listed below.

- Wells Fargo & Company. A United States based international banking and financial services institution. In 2016 Forbes magazine and Bloomberg magazine respectively listed Wells Fargo as the 7th largest public company internationally and the 2nd largest bank internationally.

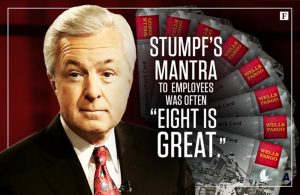

- John Stumpf, Former CEO of Wells Fargo. A self-professed small town American, John Stumpf was the CEO of Wells Fargo since 2007. He stepped down as CEO following extended press coverage of the fake account scandal. His yearly salary as CEO was US $19 million in 2015.

- Tim Sloan, Current CEO & President of Wells Fargo. Before the scandal Tim Sloan was the chief operating officer and president of Wells Fargo. Following the scandal he replaced John Stumpf as CEO and kept the position of president. His yearly salary as COO and president was US $11 million in 2015.

- Carrie Tolsedt, Former Head of Retail Operations for Wells Fargo. Nicknamed “the watchmaker” by colleagues for her excessive attention to detail, Carrie left Wells Fargo following the scandal. Her yearly salary as head of retail operations was US $9 million in 2015.

- Customers of Wells Fargo. Customers were exploited, often without their knowledge or consent.

- Employees of Wells Fargo. Many employees were victims of this scandal and many were complicit.

- Prudential is a Fortune 500 insurance company. It placed self-service computers in Wells Fargo retail-banking branches to sell life insurance policies.

Instruments Involved

The main instruments involved in the scandal are listed below.

- “Eight is great”. A saying that was the foundation for an aggressive cross-selling target scheme advocated by Former CEO John Stumpf in the Wells Fargo retail-banking division. The “eight is great” scheme set the target for accounts per customer at eight. Employees had to reach “eight is great” targets in order to earn commissions and avoid termination.

- Perverse incentives. Refers to incentives that have unintended and undesirable results. Some economists argue perverse incentives were partially to blame for the recent 2008 financial crisis. Perverse incentives played a large role in the Wells Fargo fake account scandal.

- U5 forms. Banks record information about former employees on these forms. This information is then shared between banks. This practice was developed in-order to bar fraudulent employees from the banking industry. Negative feedback on a U5 form ensures a former employee will have difficulty regaining employment in banking.

- Forced arbitration. Under forced arbitration a customer can only submit disputes to a binding arbitration process. Customers in this process have waived their right to sue, to participate in a class action lawsuit, or to appeal the outcome of arbitration. Forced arbitration is often biased in favor of corporations.

- Clawback provision. These stipulations are usually in executive employment contracts. They allow companies to reduce or cancel bonuses as a punitive measure against former and current employees. Bonuses subject to clawback are usually unvested stock awards.

Events

The first indication of rampant unethical practices at Wells Fargo emerged from a 2013 report by the Los Angeles Times. The report stated Wells Fargo had an unhealthy “pressure-cooker” sales culture. Several regulatory bodies opened investigations into Wells Fargo following the article.

Californian and federal regulators took three additional years to take action against Wells Fargo. On September 8, 2016 they finally fined the bank $185 million US. Investigators discovered the “pressure-cooker” sales culture led Wells Fargo employees to create of over 2 million accounts without customer consent. The “pressure-cooker” sales culture was a result of CEO John Stumpf’s “eight is great” sales targets. Accounts fraudulently created by employees included credit cards, checking accounts, saving accounts, mortgages, and loans. Wells Fargo profited $5 million dollars from fraudulent accounts during the 5 years the practice was widespread.

“Eight is great” targets were set to an unattainable level. Whilst the target for average number of accounts per customer at Wells Fargo was 8, the actual number of accounts per customer was 5.9 in 2011 and 6.1 in 2015. Four years of “eight is great” targets and widespread fraudulent behavior had only increased the average by 0.2. This unrealistic goal made it extremely difficult for employees to meet their targets, which resulted in fraudulent behavior. Perverse incentives arising from “eight is great” targets played a significant role in the scandal.

Wells Fargo retail-banking employees revealed they often faced abuse if they did not meet their “eight is great” targets. Employees reported incidences of managers yelling in their faces and feeling an “unbearable” pressure to achieve sales targets. Managers even threatened underperforming employees they would “…end up working for McDonalds”. Employees terminated for not reaching targets reported facing retaliatory U5 forms that effectively barred them from employment in the banking industry.

Wells Fargo has admitted fault for a well-documented attitude of seemingly willful ignorance towards fraud committed by employees dating back to 2011. Employees were ignored or retaliated against when reporting fraudulent behavior to confidential ethics lines or upper management.

In a particularly egregious case a former employee claimed his store manager targeted him after he reported fraudulent behavior by other employees to a state manager. The store manager forced him to retract his statement, then framed him for fraud. The termination reason on his U5 form was listed as fraud, which barred him from employment at other banks.

During the period of “eight is great” Wells Fargo was one of the most profitable banks in the US, and executives were awarded large bonuses. John Stumpf profited 200 million dollars solely from the increase in Wells Fargo’s stock price over those years.

Outcome

Resignations and Clawbacks

Upon internal investigation into fraudulent accounts Wells Fargo dismissed 5300 retail-banking employees. These dismissals came after the bank was fined by the regulatory agencies. The scale and timing of the dismissals suggests Well Fargo executives had systematically mismanaged incidences of fraud.

Following the dismissals John Stumpf was called to testify in front of the US House of Representatives Financial Services Committee on the 20th of September 2016. Senator Elizabeth Warren sternly stated to Stumpf that he should resign, return his profits and be criminally investigated.

Almost a month afterwards on the 12th of October 2016 John Stumpf resigned and was succeeded by Tim Sloan, COO and President of Wells Fargo. Stumpf was subject to a clawback provision and forfeited $41 million of unvested stock awards due to his role in the scandal.

Carrie Tolsedt, the executive responsible for the retail-banking division faced a similar punishment. She had already left the retail-banking division role in July but had continued with the company. When she resigned she received a $124.6 million dollar payout and forfeited $19 million of unvested stock awards in a clawback. The practice of giving executives large payouts when dismissed is commonly referred to as a soft landing.

Unvested stock awards are paid to executives based on performance. The total value would only be paid to executives if the company enjoyed robust future performance. Realistically the punitive figures released to the public are much lower, and the inflated figures have given us a false sense of justice.

Wells Fargo tries to lessen its punishment and payouts

Wells Fargo’s public response to the scandal was to admit fault and embark on an extensive advertising campaign. Privately the bank is attempting to minimize costs and avoid responsibility. The cost of the scandal is relatively low for Wells Fargo, with legal fees estimates of $700 million.

Wells Fargo stopped individual and class action lawsuits against them by enforcing forced arbitration clauses. When opening new accounts at Wells Fargo, customers consent to forced arbitration. Victims of the fraudulent accounts scandal have stated they could not have given consent to forced arbitration as they never gave consent to opening the accounts. Judges have ruled against that argument in favor of Wells Fargo and forced arbitration. US Senator Sherrod Brown has introduced a bill to the senate, which would override forced arbitration cases for Wells Fargo customers. It has not yet passed into law. The bill did not pass, but was reintroduced by Rep. Brad Sherman (D) in March 2017. The bill is still not likely to pass in the Republican controlled Congress.

Prudential suspends Wells Fargo selling its insurance products

A group of Prudential’s former employees filed a wrongful termination suit in November 2016 claiming they were dismissed for escalating concerns about fraudulent conduct at Wells Fargo. Upon investigation, the former employees claim Wells Fargo employees were also creating unauthorized life insurance policies. The fraudulent policies were often created on behalf of minorities, especially those who were non-native English speakers. Wells Fargo retail-banking employees are not licensed to sell insurance. Yet these same employees were assigned sales targets for insurance policies. Prudential responded to the lawsuit going public by suspending Wells Fargo’s ability to sell Prudential’s life insurance products.

Racist practices at the bank extended to denying student loans to young immigrants, according to a lawsuit filed by plaintiff and young immigrant student Mitzie Perez in March 2017.

The Department of Justice and the California attorney general started criminal investigations into Wells Fargo executives in November 2016. Two Californian Wells Fargo executives have subsequently departed from the bank in March 2017. Four lower-level executives were fired in weeks prior, and high-level executives including Tim Sloan had their wages cut by $32 million in total. The bank stated the pay was intended to ensure the “accountability of the company’s leadership for the issues arising from the community bank’s sales practices”.

The outcome of numerous cases against Wells Fargo and the total sum of consequences they face from the scandal is yet to be determined.

Ethics Analysis

Perverse Incentives

Executive Compensation & Clawback Provisions

Executive compensation schemes are designed to avoid conflicts of interest between executives and shareholders. This is achieved via partially remunerating executives with company stock. Perverse incentives arise from these compensation schemes, as stock ownership encourages executives to aim for short-term growth and engage in risky behavior. This focus can endanger the long-term health of a company. Clawback provisions are added to executive employment contracts to discourage excessive risk-taking. Unfortunately in regards to Wells Fargo, clawback provisions proved to be weak and ineffectual.

Executives are economically rational actors. The perverse incentive structure of “eight is great” would not have become company policy if executives believed clawback provisions represented a considerable risk to their compensation. This same logic follows for demonstrably willful ignorance regarding the high incidence of fraud in the company. John Stumpf profited $200 million from stock awards during the scandal. He was penalized only $41 million as remedy for “eight is great”. It is clear from these numbers that clawback provisions at Wells Fargo lacked the severity required to effectively punish executives.

Professors Lucian Arye Bebchuk and Jesse M. Fried of Harvard and Berkley respectively, studied the role of executive compensation schemes in encouraging dishonest behavior by executives. In their 2005 study titled “Executive compensation at Fannie Mae: a case study of perverse incentives, nonperformance pay” they found empirical evidence of executive compensation encouraging executives at Fannie Mae to fraudulently misreport company earnings. Following the discovery of this fraudulent activity, executives at Fannie Mae left the bank with large severance packages. Carrie Tolsedt enjoyed a similar ‘soft landing’ arrangement with Wells Fargo. Clawback provisions were adopted at Wells Fargo to avoid encouraging fraudulent behavior such as that encountered at Fannie Mae. Evidently clawback provisions need reform as similar behavior occurred at Wells Fargo despite their use. More severe action is required.

Employees & “Eight is Great”

The “eight is great” targets were designed to be unattainable for a vast majority of employees. Staff who were least capable of reaching their targets faced abuse, termination, and U5 forms. Confidential ethics lines and complaint processes were corrupted, as they did not help executives and management reach their goals. The employees who committed fraud failed to act ethically, however it cannot be understated they were immersed in an unethical working environment. Executives and management allowed numerous unethical practices to occur as they demanded higher productivity from employees. The Wells Fargo fake account scandal exemplifies how consequences of perverse incentives spread through a company from high to lower level employees.

Customers & Shareholders

Customers and shareholders of Wells Fargo were the main victims of perverse incentives. Minorities were targeted and fraudulently sold insurance policies. Customers who are attempting to seek justice are unfairly blocked by forced arbitration. Punitive clawbacks were reported at an inflated rate in an attempt to quell public outrage. Fines directed at public companies such as Wells Fargo are simply passed onto stockholders and consumers. While customers were charged $5 million for the accounts, the real cost to them is unknown. Bad credit, overdrawn accounts and flow on effects from fees would have certainly destroyed many lives. The most vulnerable Americans suffered the most from this scandal.

Ethical Considerations

Deontological ethics states that agents have a duty to act in accordance to a moral principle. For executives the moral rule was to uphold the interests of shareholders, employees and other stakeholders by avoiding excessively risky behavior. Wells Fargo executives failed to fulfill this duty. As people do not always adhere to deontological ethics, the agent-principal dynamic is inherently flawed. Hence, executive compensation schemes aim to align the interests of executives and shareholders via stock bonuses. Unfortunately this solution created its own perverse incentives, which were not effectively mitigated by clawback provisions. The top-down spread of perverse incentives led to pervasive of unethical practices throughout the organization, from executives to employees.

Unethical practices by executives and employees at Wells Fargo included:

- Setting unattainable targets

- Abusing employees

- Creating fraudulent accounts

- Fraudulent insurance selling

- Ignoring reports of fraud

- Targeting minorities

- Forced arbitration

- Exploitation of U5 forms

Recommendations

Seven Pillars Institute discussed the lack of ethical and economic justification for current rates of executive compensation in the case study on the subject. We have further established in this case study we cannot always expect ethical behavior from executives or employees. If people are incentivized to act fraudulently we can expect fraud. To effectively deal with the issue of fraudulent activity we need to address executive bonuses, as perverse incentives spread from the top-down. Reducing the incentive for executives to allow and contribute towards fraudulent activity can be achieved via harsher clawback provisions, enforcement of criminal and fiscal penalties for executives, deferred compensation or removal of stock incentives completely.

Executives are powerful and financially motivated; we cannot expect reform of executive compensation to occur quickly. In a capitalist society wages equal labor power, not labour worth. Often the level to which executives exploit employees matches the exploitability of employees. From 1994 to 2002 union membership in the finance, insurance and real estate industries fell from 2.7% to 2.0%. In the retail sector it fell from 5.4% to 4.1%. Both of these industries are significantly lower than the nationwide average in 2002 of 11.9%. The nationwide average in 1955 was 27%.

Unions provide legal representation for employees who face abuse by management and unfair U5 forms. Strong union membership would reduce the ability of executives to pass the burden of perverse incentives onto employees. This would not fix the issue of perverse incentives, but would protect otherwise easily exploited employees.

In the case of Wells Fargo, almost all significant progressive actions to bolster the rights of consumers have been undertaken by Democrats. Yet, regulation of banking and protection of the public and employees must be advocated as bipartisan values and fought for by those who wish to avoid recurrence of similar bank frauds in the future.

Photograph courtesy of Forbes.com