Universal Basic Income: More Empirical Studies

Part 3 of SPI’s Universal Basic Income Series

New universal basic income (UBI) experiments around the world provide fresh data for evaluating the feasibility and efficacy of the idea.

Canada, 1974 – 1978:

In 1974, Canada began the largest social experiment in the country’s history. Named The Manitoba Annual Income Experiment(The Mincome Experiment), this experiment became one of the first examples of a UBI program applicable to an entire population, and thus serves as a rare example of the impact UBI has on both community and individual outcomes. Prompted by growing institutional awareness and concern over poverty proliferation within Canada, radical changes to Canada’s social-welfare structure became a public priority (Special Senate Committee on Poverty). As a solution, the Canadian government, in conjunction with the Manitoba provincial government, began the Mincome experiment to fashion a new means of welfare facilitation.

This case study focuses on just one part of the Mincome experiment. The small, rural Manitoban town of Dauphin was the only site of the Mincome experiment to receive a UBI. Other sites of the Mincome experiment such as Winnipeg or other dispersed rural sites were monitored as randomized control trials (Forget 288). Incomes in these locales were provided randomly to a very small proportion of the population and thus do not qualify as useful in an evaluation of UBI.

The objectives of Mincome fell into three major categories: evaluate economics, identify logistical challenges, and understand ramifications. Firstly, in investigating new mechanisms for welfare facilitation, the Canadian government wished to “evaluate the economic and social consequences of an alternative social welfare system based on the concept of a negative income tax” (Hum, Laub and Powell 1) and specifically what this would entail for labour supply outcomes. In the context of a UBI, a negative tax rate is defined as a tax rate which determines how much of a basic income is removed “per dollar of family income and net worth” (Simpson, Mason and Godwin 86). Secondly, and implicitly, including Dauphin as a rural “saturation” site allowed for Mincome’s operators to better understand the logistical, administrative, and social challenges associated with the implementation of a UBI program throughout an entire population (“Income Maintenance and the Canadian Mincome Experiment” 45). Thirdly, by implementing a universal program in an isolated community such as Dauphin, researchers anticipated the possibility of aggregate demand effects (Forget 289) that would aid in understanding the macroeconomic ramifications of a UBI.

The reason for the choice of Dauphin as the site for universal treatment was its classification as a low-income town, where the impacts of a UBI would be most prominently felt. Every resident of Dauphin fell within the income ceiling of $9,000 per family required to qualify for Mincome treatment (Simpson, Mason and Godwin 88). Within Dauphin, all 586 families received CAD$3,800 per year with a negative tax rate of 50%, an amount of money which in 2016 prices corresponds to approximately CAD$18,900 (Ibid 98). These payments continued for approximately three years until 1978, after which funding was cancelled following the completion of data collection. This cancellation occurred before any actual analysis of data was completed (Widerquist 54). The abrupt end to such a large experiment was the culmination of several factors: the severe lack of funding and underestimation of costs was the most significant. This factor was partly fuelled by high rates of inflation seen throughout the 1970s, as well as the changing intellectual and ideological environment of the era, which prompted a large reorganization of social priorities. Overall, this abrupt end meant no immediate evaluation of the program occurred. It was not until years or even decades later that any useful analysis of the data collected became published.

In the case of Dauphin, no researchers paid individual attention to the town until the 21stcentury. This lack of attention is likely due to the fact that Dauphin was the only site throughout the North American income experiment saga of the 1960s and 1970s which received a universal basic income, rather than serving as a randomized control trial. Economists and other social researchers of the era undoubtedly labelled this a major weakness of the experiment in evaluating the effects of income maintenance, as a lack of randomization does not allow for an “uncontaminated (econometrically consistent) estimation of behavioural response to guaranteed income treatments” (Simpson, Mason and Godwin 87), something which by default labelled the experience of Dauphin as useless in their analysis. However, this lack of randomization allowed for a number of rather unique and positive impacts on the community of Dauphin, results which would not have been possible in a randomized environment.

Improved Health Outcomes

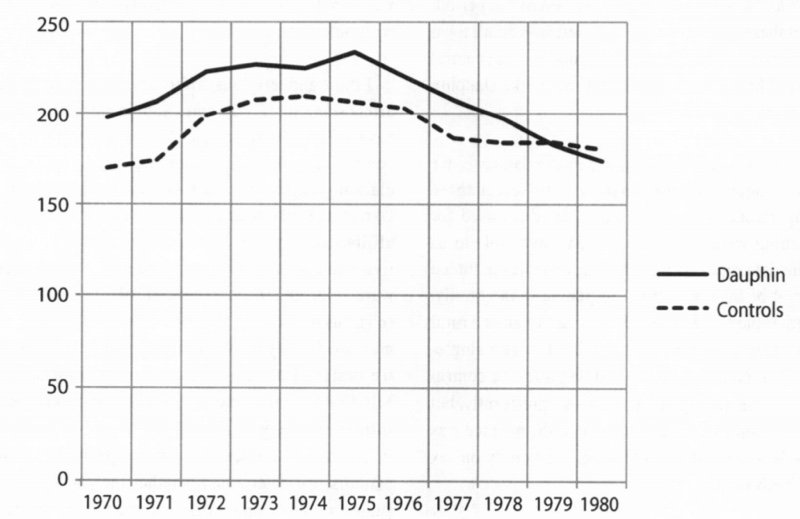

The work of Evelyn Forget has been the most significant in investigating the results of the UBI program in Dauphin. Her investigations are responsible for important and welcome improvements in health and education indicators community-wide. The most prominent findings pertain to the sizeable reductions in hospitalization rates experienced throughout the relatively short duration of Mincome. Before the Mincome experiment, hospitalization rates were 8.5% higher in Dauphin relative to the other control groups in rural Manitoba. However, as seen in Graph 1, by 1978 this gap in hospitalization rates had all but closed. Specifically, Forget found that during the Mincome experiment this reduction in hospitalization rates was most impacted by the respective decline in hospitalizations relating to both ‘injury and accidents’ as well as ‘mental health diagnoses’ (296). Forget claims these two categories of hospitalization are highly correlated with low socio-economic status, implying an impact on health outcomes via the income security provided by a UBI (Ibid). From this, Forget (300) concludes a UBI shows major potential to “improve health and social outcomes at the community level… [and] is worth examining more closely in an era characterized by concern about the increasing burden of healthcare costs”.

Graph 1: Hospitalization Rates in Manitoba (Dauphin and Rural Controls) Source: Forget p. 294

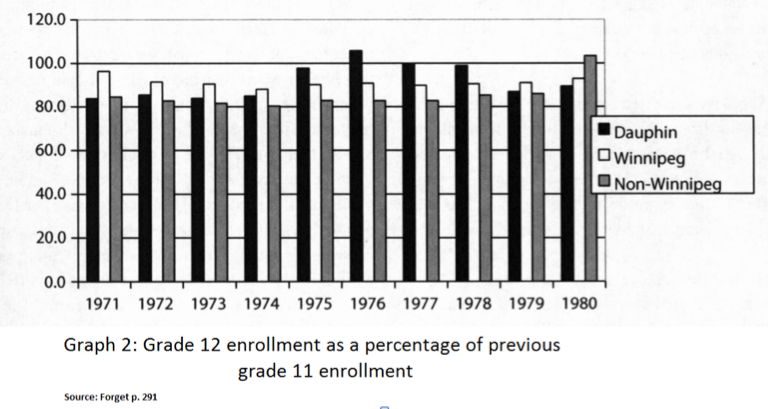

Apart from the UBI’s impact on health indicators, Forget also found that throughout the duration of Mincome, grade 12 enrolments increased markedly. As is seen below in Graph 2, throughout the experiment Dauphin residents exceeded both the Winnipeg and non-Winnipeg enrolment rates for grade 12. Forget hypothesizes a social multiplier working to improve enrolment statistics (291). In enrolling for grade 12, students would likely consider both anticipated family income (supplemented by Mincome) as well as the number of their friends also enrolling, a number reinforced by this supplementation of family income. Considering Dauphin data was deliberately ignored in research by economists, it is ironic that a key takeaway from the experience of Dauphin is derived precisely and purely from this lack of randomization, “a response that would be invisible in a classic randomized experimental site” (Forget 292).

Destigmatization of Welfare

Aside from the work produced by Forget, few researchers or studies have empirically investigated Dauphin’s experience with a UBI. Calnitsky was able to qualitatively demonstrate the impacts of Mincome, showing that in Dauphin the universality of UBI destigmatized social welfare as it did not single out unable or incapable recipients – strengthening the impact of any given government welfare. Conversely, Widerquist, as well as Hum and Simpson’s paper “Economic Response to a Guaranteed Annual Income,” state that throughout the North-American social experiment saga of the 1960s and 1970s the expected impacts of an income guarantee program on labour supply were substantially overestimated throughout both the United States and Canada. Read together, the research by Forget, Calnitsky, Widerquist, Hum, and Simpson suggest a UBI allows people to participate in social welfare without shame and does not lead to a decrease in labour productivity.

Overall, this research demonstrates clear support for the implementation of UBI schemes in the future. By demonstrating vast increases in health outcomes given the relative duration of the experiment, supplemented by very minimal side-effects in labour supply, the experience should serve as an example of the merits a UBI may hold for the future of Canadian society. It emphasises the strength of truly universal payments and makes a case against experiments which choose to implement targeted samples. All these elements of research design are no doubt in the minds of current policy makers who have this year begun a dedicated UBI experiment throughout the region of Ontario.

The Problem of Funding

However, regardless of these encouraging community outcomes, the problem of affordability remains UBI’s most pertinent criticism in evaluating the experience of Dauphin. Regardless of the benefits, as has already been stated, the Mincome experiment was promptly defunded in 1978 after the cost of the experiment was deemed too high by the Canadian federal government. However, was this due to the cost of the policy itself (implying a structural deficiency in funding a UBI), or were there other factors at play which prematurely ended the program (causing a contextual justification of its cancellation)? The latter is probably true for the following reasons.

Firstly, as Canada’s first major social experiment of this scale, the rapid overshooting of budget estimates should barely be surprising. Aside from a general naivety of funding estimates, a key reason for this overshooting can be seen in the clear lack of focus in the project design, with research priorities changing noticeably throughout the course of the experiment. Starting as a study concerned purely with the impacts of income maintenance on labour supply, the focus of data collection broadened substantially over time as those involved with Mincome became much more invested in several sociological and psychological sub-studies (Simpson, Mason and Godwin 90). What this shows is support for the notion that the problem with Mincome was its design and leadership and not a problem with UBI itself. Had the experiment facilitators been disciplined enough to maintain focus throughout its lifetime, it would have presumably lasted much longer and have been much less costly.

Secondly, the size of the Mincome research team was enormous, and is something that would not be encountered in modern circumstances. At its peak, Mincome staff numbered around 200, with most of these being involved in administration, interviewing, and questionnaire processing (Ibid). In a modern version of this experiment, given the advent of technology since the 1970s, much of these costs can be avoided through the automation of payments and data collection, something already achieved in Finland’s own pilot project. Finland presents the perfect solution to this problem of large, expensive pools of staff as it chooses to collect relevant research data through registry data instead of interviews or questionnaires. Although this approach to experiment design was adopted as a means to minimize observer effects, it has the side effect of lowering experiment costs, which contributes greatly to the affordability of a UBI.

Therefore, it seems fair to conclude affordability of the Mincome experiment came down to design and administrative faults, factors which should be interpreted as independent of the merits of UBI – and are more a reflection of Canada’s circumstances at the time.

Namibia, 2008 – 2016:

In January 2008, the village of Otjivero in rural Namibia became the site of the world’s first official UBI program, technically referred to as a Basic Income Guarantee (BIG) project. This project was a “pilot project” in that it was established with the aim of convincing the Namibian federal government the merits of such an approach to social policy. Funding for this project came from several sponsors both national and international. These sponsors are presumably associated with the Namibian BIG Coalition, although published findings did not specifically disclose donors (Osterkamp 74). It should be noted the Namibian BIG Coalition is a coalition intellectually dedicated to the core ideas of the UBI movement, with membership composed of organisations such as trade unions, missionaries, and NGOs. Additionally, this project was not at all funded by the Namibian federal government, which has been consistently dismissive of both the possibilities and results of a BIG program (Haarmann and Haarmann 7).

Empirical studies pertaining to Otjivero and the BIG project are limited to the assessment reports published by researchers affiliated with the Namibian BIG Coalition in September 2008 and April 2009, on data six and twelve months after the beginning of the project respectively. Both the lack of breadth in research and the association of its authors pose some serious issues in objectively assessing the outcomes of Otjivero (Osterkamp). Additionally, no further research was ever completed regarding Otjivero’s development after the published report in April 2009, meaning no long-term impacts of the BIG have ever been recorded. However, despite this there are still some key positive lessons from the experience of this rural Namibian village.

In January 2008, every resident of Otjivero began receiving unconditional cash payments for a two-year period, after which the payments were markedly lowered. The only people who did not receive these transfers were those over the age of 60 years, as these people qualify for state pensions. Transfers of N$100 (approximately USD$15) were made every month to the 930 eligible residents of Otjivero, whereby the mothers of relevant children were paid their respective grants (Frankman 527). After this initial two-year period, payments were cut to N$80, and finally halted in 2016as the federal government officially rejected this progressive approach to social policy in favour of one based on economic growth.

Profiled as a low-income rural area, Otjivero is located approximately 100 kilometres east of the nation’s capital Windhoek. Regarding sample size and methods, assessment reports detail that “the sample for the evaluation study was randomly drawn, covering about 50 out of 200 households” (“2008 Assessment Report” 37). Additionally, researchers claim the age and gender distribution of Otjivero are representative of Namibia as a whole, hence justifying its choice for the BIG project locale (Ibid). Payments were administered electronically via the Namibian postal service, forcing all recipients to become integrated into the formal banking system, another benefit of this BIG (Ibid 18).

Positive Health and Social Outcomes

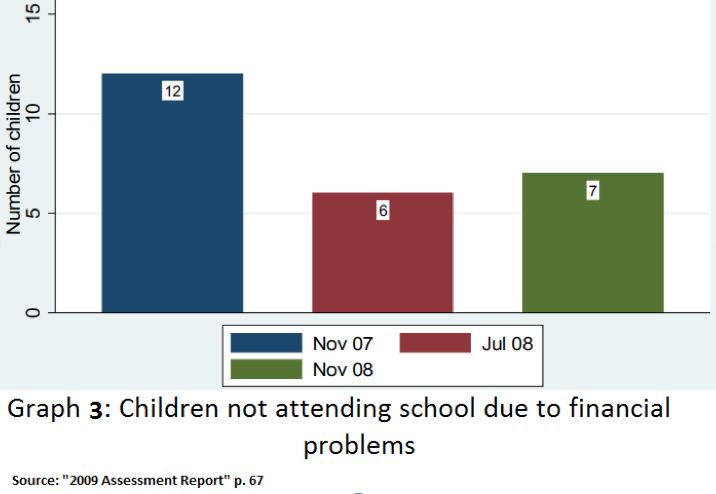

After a full year of this BIG project’s operation within Otjivero, the assessment report of 2009 showed promising results for ending the vicious cycle of poverty, which has become a staple of life within this village. Most significantly, these monthly payments seemed to have the largest impact on the rate of malnutrition for children under the age of five, which declined from 42% of all children in Otjivero in November 2007 to just 10% in November 2008 (“2009 Assessment Report” 55). The local health clinic recorded a five-fold increase in revenue, increasing from N$250 per month to N$1300 (Ibid 56). For the first time, antiretroviral (ARV) drugs for the treatment of HIV/AIDS became readily available in Otjivero as it soon became worthwhile for doctors to come and treat people now able to pay, meaning patients did not have to pay for costly transport to the nearest treatment clinic in the city of Gobabis (Ibid 59). Social indicators such as school enrollment rates improved dramatically (Ibid 66-68). The number of children not attending school because of financial struggles practically halved; as is shown in Graph 2. The BIG was also heralded for “significantly reduc[ing] crimes relating to desperation (poaching, trespassing, petty theft) and thus appears also to have improved the general quality of life in the community” (Ibid 47). What all these outcomes reflect is the impact universal incomes can have on a community, even one as small as Otjivero. However, what must also be noted in these assessment reports is the clear lack of academically consistent empirical methods, both in their design and results.

Shortcomings of Methodology

Osterkamp gives a compelling critique of the two assessment reports on the Otjivero BIG project. Osterkamp challenges the design of the research carried out by Haarmann et al., questioning whether the problems created by the design can allow objective validation of their findings. Most notably, this clear lack of transparency in methodology means there is no viable way of cross-referencing or independently evaluating their findings. No copies of the data sets constructed from sample surveys, nor the interviews used to create them, were ever made accessible to the public, as the researchers refused to release their database on the grounds of privacy for the residents of the village (Osterkamp 80). Furthermore, in the reports, ‘income’ is not consistently defined, such that figures and graphs concerning income are not directly comparable between reports. Given the gravity of the term ‘income’ in any economic report, this only adds to the ambiguity of this project’s design. Finally, Osterkamp is also keen to point out that there is a clear lack of neutral expertise in the empirical literature surrounding Namibia’s BIG project, noting all research and implementation of the BIG has been carried out by researchers and organisations which are “exclusively BIG proponents” (Ibid 79). Again, this pokes holes in the credibility of assessment reports, which should be fashioned around objective assessments where it is “of utmost importance to argue soberly and to present convincing evidence” (Ibid 90).

Overall, Osterkamp’s assessment of the research gathered surrounding Namibia’s BIG project casts a veritable shadow over the encouraging results presented by Haarmann et al. Whilst this research no doubt reinforces the positive impacts of UBI on communities already given throughout these case studies, the clear issues presented in Namibia’s case remind us of the need for comprehensive and rigorous modes of empirical research. By compromising on the quality of research, one compromises the scope of impact a project can have and may be the reason for relatively few other UBI experiments in Africa. Simply put, the lack of credibility in these reports has hampered the likelihood of governments to seriously contemplate the usefulness of UBIs in achieving social improvement despite the incredibly positive results researchers derived from them.

Iran, 2010 – Current

In December 2010, the Iranian government embarked on a series of ambitious reforms to the country’s extensive subsidy program, and as a result, became the first country in the world to provide a UBI to all its citizens. Throughout most of its history, much of Iran’s state assistance has taken the form of energy and food subsidies, whereby prices are kept much lower than international levels to ensure all members of society are allowed access to basic commodities such as food and oil. However, over time, such a system has become associated with high levels of inefficiency, waste, and inequality with 70% of the total subsidy bill going to the richest 30% of the population (“TV address by President Ahmadinejad”). Thus, in response, the Ahmadinejad administration in 2008 began plans to replace a substantial proportion of subsidy expenditures with cash subsidies, with the intent of reducing production inefficiencies and inequality in Iran.

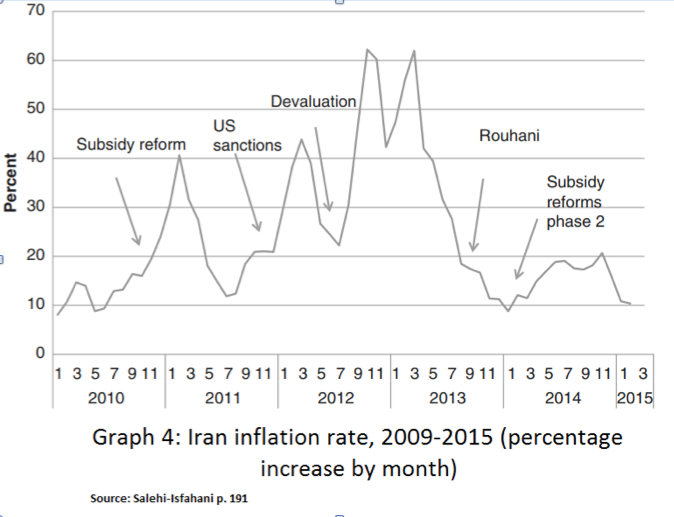

Given the extreme size of the subsidy program in Iran, this put the country in a unique position in establishing a UBI where the government needed only to redistribute current expenditures instead of incurring new revenue streams. Prior to the reforms in 2010, subsidies cost the Iranian government around USD$100 billion per year and accounted for approximately 30% of GDP (Tabatabai 4). On 19 December 2010, these price subsidies were immediately halved to maximize public support for the reforms. Support was achieved by maximising the “nominal amount of compensatory payments made to households” (Guillaume et al. 12). Unsurprisingly, this caused huge price increases throughout Iran, causing the price of bread and energy to rise by factors of anywhere between two and nine (Salehi-Isfahani and Mostafavi-Dehoozi 7). Also unsurprising is Iran experienced large fluctuations in inflation (see below). Simultaneously, a cash transfer valued at USD$45 was made to 80% of the Iranian population, a proportion which increased to 97% by mid-2011 (Tabatabai 14-15). Despite still running in its current form, falling commodity prices have put considerable strainon the Iranian government to provide a UBI for all citizens. In 2014, as a reflection of the ongoing economic turmoil in Iran and subsequent prolonged exchange rate devaluations, this UBI was officially valued at USD$17 by the Central Bank of Iran (Soleimaninejadian and Yang 2598). In 2016 these continuing circumstances resulted in an unpopular decision by parliament to cut payments to 24 million Iranian citizens.

Decreased Poverty and Inequality

The initial results of this program, prior to the cut to its universality, were quite impressive and made substantial impacts on the rate of poverty and inequality in Iran without any significantly adverse impacts on labour supply, a common critique of UBI initiatives. Unsurprisingly, these transfers had a large impact on the rate of poverty in Iran given that USD$45 accounts for 49.3% of monthly expenditures for those in Iran’s bottom quintile and 24.7% for those in the second quintile (Salehi-Isfahani and Mostafavi-Dehoozi 22). One study concludes that this UBI has had a substantial impact on poverty indicators, causing the percentage of individuals living below the poverty line (the headcount ratio) to fall from 10.2% in 2009 to 5.1% in 2012 (Salehi-Isfahani 192). Inequality also declined; Soleimaninejadian and Yang (2600) found a drop in the Gini coefficient from 0.4191 to 0.3367 between the years of 2010 and 2014, whilst Salehi-Isfahani (193) found similar results between the years of 2009 and 2012. Finally, and importantly, Salehi-Isfahani and Mostafavi-Dehoozi fail to produce empirical evidence of a general link between these subsidy reforms and Iranian labour supply, emphatic in their refutation of “cash transfers make poor people lazy” (13) as an unsubstantiated argument against UBI lacking empirical support.

Bad Timing

Despite all these encouraging economic results, a serious impediment to an institutional acceptance of UBI has been the sustained issues Iran has had with inflation since the implementation of a UBI. Much of the blame for inflation falls upon the 2010 subsidy reforms. However, one of the greatest curses of these subsidy reforms has been their timing, only months after transfers began Iran was hit with tough international sanctionsby the U.S. and other western nations in reaction against its nuclear activities. The sanctions caused a prolonged period of economic recession and a subsequent spiralling of inflation rates.

Additionally, Salehi-Isfahani (191) points towards fiscal irresponsibility of the federal Iranian government in causing another much more damaging bout of inflation in 2012. This fiscal irresponsibility was manifested through the funding of a low-income housing project, where funding occurred simply through printing the sufficient amount of money required for its construction, in turn violating one of the most rudimentary tenets of good economic management. Graph 4 does well in setting the record straight on Iran’s inflationary fluctuations. Whilst the subsidy reforms had a substantial impact on inflation, the U.S. sanctions (2011) and money printing episode by the federal government (2012) impacted the Iranian economy to either similar, or much more severe degrees.

Thus, it would be incorrect to blame the subsidy reforms as the prime catalyst of Iran’s economic instability since 2010, and therefore also incorrect to use these grounds to delegitimize their deserved place in Iranian social policy.

Overall, what we see in Iran is quite strong evidence in support of implementing more large scale UBIs throughout the world. However, the problems and particularities of Iran’s experience can be used as powerful lessons for future national implementations of UBIs. Firstly, and most interestingly, Iran has no ideological attachment to the idea of a UBI in the same manner as other (typically European) countries do, particularly regarding arguments about the human right to an income (Tabatabai 18). Essentially, the Iranian UBI arose out of a political desire to re-establish government provisions for its citizens, something that was only possible due to the incredibly extensive pre-existing pool of government revenues already being used as state expenditures. Given that Iran’s case is the first example of a UBI (de facto or otherwise) being implemented nationwide, this mode of financing raises a very important question about the logistics of funding. Would other countries, primarily those highly liberalized and free-trade orientated, ever be able to establish a UBI under this mechanism? Most likely not. Additionally, Iran’s recent scaling back of this program both in value and population scope is also indicative of the problems associated with funding major public ventures on the back of commodity revenue and exports such as oil in the case of Iran. However, this should be considered a more general critique of Iran’s economic diversity than their problems with universal transfers.

Despite the funding issue, Iran serves as a sterling example of what can be achieved with UBI. Evidence suggests the implementation of UBI leads to a decrease in poverty and inequality, without impacting levels of employment. It appears geopolitics, poor fiscal management, and volatility of commodity prices are the main factors affecting the longevity of Iran’s UBI. These factors are independent of the mechanics of the universal transfer scheme, and as such should be judged independently on its own merit.

Universal Basic Income Experiments, 2017:

Finland

In terms of publicly funded UBI projects, 2017 saw the launching of experiments in Canada and Finland, as well as in Spain. In Finland, a basic income experiment was launched on 1 January 2017 concerning an experimental size of 2,000 persons randomly selected between the ages of 25 and 58, pulled from the existing pool of unemployment benefit recipients in Finland. This program, enacted by Finnish social security provider Kela, gives program participants unconditional monthly payments of €560 which will continue until December 2018. This experiment will not conduct any interviews or questionnaires of participants throughout the duration of this project in an effort to avoid observer effects, instead opting to gather analysis autonomously via register data. No results of this experiment will be published until 2019.

Canada

In April 2017, Canada also began a basic income experiment, its second iteration in Canadian history, this time in the region of Ontario. Much like in the case of Dauphin, Ontario’s pilot projectrests largely upon the mechanics of a negative income tax as a core principle of its facilitation. This pilot project allots up to CAD$16,989 per year for single participants and CAD$24,027 for couples at a negative tax rate of 50%. Meaning that “those who work will see the amount of their basic income reduced by 50 cents for every dollar they earn” (Kassam 6). Additionally, the only criteria for program selection is low-income status and is not contingent on being a current welfare recipient. By October 2017, this program had enrolled 400 people, with plans for expansion of up to 4,000 people throughout various locales within Ontario. Surveys will be completed regularly by participants which will concern several economic, social, and psychological outcomes (unlike in Finland) with payments being distributed monthly. This experiment is planned to continue for three years, where findings are expected to be published in 2020.

Spain

In Spain, Barcelona’s trial of a basic income also looks to add to the exciting array of UBI experiments in 2017. Dubbed B-MINCOMEin a direct referenceto Canada’s original basic income experiment, this experiment is one of the few in the world being launched at the municipal level by the Social Rights Area of the Barcelona City Council. Carried out in the city’s poorest region, Besòs Axis, between September 2017 and December 2019, treatment groups are differentiated through their conditionality (or unconditionality) of treatment to test both existing and alternative means of welfare provision. Of the 1,000 treatment households, 550 will need to participate in one of four active social policies to receive their basic income. These policies, named ‘active sociolaboratory policies’, include programs such as “an occupation and education program, a social and cooperative economy program, a guaranteed housing program, and a community participation program” (Mcfarland 45). The other 450 will receive their payments unconditionally in an effort to test the merits of a UBI on social outcomes. The specific amount of payments is varied per household according to household structure and financial status, however the range of payments is given by the city council as between €100 to €1,676 per month per household. Whilst not all experiment participants will receive unconditional income payments, this experiment will serve as particularly useful in providing a direct comparison between existing means of welfare provision and UBI, something which is particularly lacking in existing literature.

Y Combinator

Aside from publicly funded UBI experiments, several privately funded experiments are also looking to expand the empirical literature of UBI in the context of both advanced and developing economies. The Silicon Valley venture capital firm Y Combinator set out a finalised proposalfor an experiment in September 2017 to go forth in 2018. Proposed to “inform academic, policy and political debate” (Y Combinator Research 3) in the U.S., this experiment plans to illuminate the ramifications of a UBI within the U.S. context as a reaction to the growing trend of poverty within it. This experiment will involve a 1,000-person treatment group receiving USD$1,000 per month from Y Combinator for 3 to 5 years, complemented with a 2,000-person control group throughout two U.S. states. In terms of measurement, the proposal claims that the experiment will engage in both interviews with participants throughout the experiment as well as a comprehensive quantitative analysis of all relevant register and interview data both during and after completion of the experiment. Instead of simply choosing a sample from one socio-economic level, or from the existing pool of social welfare recipients, this experiment looks to be the most encompassing of the term universal. Y Combinator’s sample will feature a range of races, income levels, employment statuses, number of children, and debt levels (Ibid 13). The ability to implement such a varied sample is certainly a major strength of privately funded experiments, in that they do not need to politically justify the merits of universality to a population in a pilot project.

GiveDirectly

In November 2017, the New York based nonprofit GiveDirectly extended their UBI project in Kenya and launched the largest and longest running experiment to date. Beginning with a seemingly impromptu blog post on their website,GiveDirectly began an experiment comprised of 220 Kenyan villages scheduled to run for up to 12 years with a budget of USD$30 million, a sum raised mostly via private donors (McFarland 53). Specifically, on its websiteGiveDirectly explains this experiment will be focused on testing the effects of a UBI on both long and short-term outcomes by providing it for 12 and 2 years respectively to the villages concerned. Overall, monthly payments made to individuals will be valued at USD$23 per resident, a number which roughly equates to half of the average income in rural Kenya (Ibid). These long-term transfers will be made to 40 villages, whilst 80 villages will receive the short-term transfers, further complemented by a 100-village control group. By comparing these two treatment groups, GiveDirectly claims it can effectively measure the impact of permanency in income, something particularly important in consideration of business start-ups or individual investment in human capital. The methodology and approach to publishing for this study will be very similar to GiveDirectly’s initial 2011 study, in that surveying and publication will be conducted independently and publicly so as to reduce their own institutional bias. Given the relative scope of these short-term transfers, initial results publication is expected in 2020, after these short-term transfers have ceased.

Roosevelt Institute’s UBI Model

Aside from this collection of new UBI experiments beginning in 2017, the Roosevelt Institute’s model of the hypothetical implementation of a UBI on the U.S. economy has effectively begun serious U.S. debate over the merits of a UBI and its application to a large advanced economy. In August 2017, Nikiforos et al. published Modelling the Macroeconomic Effects of a Universal Basic Incomeon behalf of the Roosevelt Institute. The model found that implementing a UBI in the U.S. could expand the economy by up to 12.56% within the first 8 years, causing a permanent increase in income even after these initial stimulative effects wore off (Nikiforos et al. 3). To show this, Nikiforos et al. used the Keynesian Levy Macroeconometric Model created by the Bard College Levy Economics Instituteto determine the effects of different sized UBIs on the U.S. economy. These three designs of a UBI were USD$250 per month per child, USD$500 per month to all adults, and USD$1,000 per month to all adults whereby even the smallest UBI for children generated 0.79% growth in GDP compared to the counterfactual, where no UBI was implemented. The elements of “Modelling the Macroeconomic Effects” which were most controversial were the micro and macroeconomic assumptions it relied on to make its findings: (1) that unconditional transfers do not impact labour supply; and (2) increasing government taxes does not impact an individual’s incentive to work. Additionally, this paper also latches onto the growing consensus in macroeconomic academia by assuming that (3) the U.S. economy is operating well below full capacity, and that growth since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) has been diminished due to a general lack of domestic aggregate demand required to generate growth (Cynamon and Fazzari; Mason; Dynan; Palley). These assumptions have serious implications for the possible impact a UBI could have on the U.S. economy by giving a mechanism through which to create aggregate demand.

Whilst at face value these assumptions may seem contentious, they are ultimately telling of the Roosevelt Institute’s more encompassing and progressive approach to economic modelling. To justify their first assumption, Nikiforos et al. refer to another recent publicationby the Roosevelt Institute which reviews labour supply research from the North American income management experiments in the 1960s and 1970s (which Dauphin was a part of) and the Alaskan Permanent Fund, whereby the author Marinescu in a blog postconcludes that “our fear that people will quit their jobs en masse if provided with cash for free is false and misguided” (4). Marinescu concludes that the only impact a UBI has on working patterns is that it makes them more flexible, and that whilst this creates minor reductions in labour supply, these are complemented by other (much more significant) increases in quality of life for the recipients. Evidence for this sentiment is also clear within the Iran case study. However, it is purely through this labour supply relationship that Nikiforos et al. derive rationale for their second assumption: that increased taxation would not impact work incentives. Believing that this assumption is a self-evident truth, they claim a lack of correlation between the large changes in effective U.S. tax rates and labour supply throughout the last several decades proves this assumption (Nikiforos et al. 15). Ultimately, this assumption comes off as a major weakness of the paper, as it lacks any substantial empirical evidence.

For their third assumption, whilst this might seem contentious for orthodox economists, the belief that an economy can perform below its productive capacity is for many an accepted feature of capitalist economies. The authors give several compelling insights as to why such a circumstance has occurred specifically in the U.S. since the GFC as an explanation for lacklustre growth since 2008. Financialization played a role in establishing unsustainable household debt levels, which caused the GFC. Household debt allowed for the continued growth of consumption despite falling wages up until the GFC (implying that post-GFC debt constraints on households are actually constraining U.S. consumption levels – thus causing demand deficiencies).

Overall, whilst one major weakness in “Modelling the Macroeconomic Effects” pervades in the form of an unsubstantiated assumption regarding the behaviour of households concerning a change in tax rates, this should not discount the overall merit of Nikiforos et al. and their findings in contributing to a discussion of UBI. As the authors note in their concluding words, this “paper is not intended to be the last word on the macroeconomic impact of unconditional cash transfers to households” (Ibid 16). The work should thus be treated as an insightful and provocative addition to the intellectual debate surrounding UBIs, a contribution which is indicative of the rapidly evolving nature of UBI’s interpretation by the academic and political mainstream.

Works Cited

National Planning Commission. “A Review of Poverty and Inequality in Namibia.” Central Bureau of Statistics, Namibia, 2008.

Calnitsky, David. ““More Normal than Welfare”: The Mincome Experiment, Stigma, and Community Experience.”Canadian Review of Sociology, vol. 53, no. 1, 2016, pp. 26-71.\

Cynamon, Barry, Fazzari, Steven. “Inequality, the Great Recession and Slow Recovery.” Cambridge Journal of Economic, vol. 40, pp. 373-399

Dynan, Karen. “Is a Household Debt Overhang holding Back Consumption?” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, vol. 2012, no. 1, 299-362.

Frankman, Myron. “Making the Difference! The BIG in Namibia; Basic Income Grant Pilot Project Assessment Report, April 2009.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies, vol. 29, no. 3, 2011, pp. 526-529.

Forget, Evelyn. “The Town with No Poverty: The Health Effects of a Canadian Guaranteed Annual Income Field Experiment.” Canadian Public Policy, vol. 37, no. 3, 2011, pp. 284-305.

Guillaume, Dominique, Zytek, Roman, Farzin, Mohammad. “Iran – The Chronicles of the Subsidy Reform.” International Monetary Fund. Working Paper: WP/11/167

Haarmann, Claudia, Haarmann, Dirk. “Piloting Basic Income in Namibia – Critical Reflection on the Process and Possible Lessons.” Paper delivered at the 14thCongress of the Basic Income Earth Network (BIEN). Munich ,14-16 September 2012, pp. 1-10.

Haarmann, Claudia, Haarmann, Dirk, Jaucha, Herbert, Shindondola-Mote, Hilma, Nattrass, Nicoli, van Niekerk, Ingrid, Samson, Michael. “Making the Difference! The BIG in Namibia; Basic Income Grant Pilot Project Assessment Report April 2008.” Namibia NGO Forum, Basic Income Grant Coalition, 2009, http://bignam.org/Publications/BIG_Assessment_report_08a.pdf.

Haarmann, Claudia, Haarmann, Dirk, Jaucha, Herbert, Shindondola-Mote, Hilma, Nattrass, Nicoli, van Niekerk, Ingrid, Samson, Michael. “Making the Difference! The BIG in Namibia; Basic Income Grant Pilot Project Assessment Report April 2009.” Namibia NGO Forum, Basic Income Grant Coalition, 2009, http://bignam.org/Publications/BIG_Assessment_report_08b.pdf.

Hum, Derek, Simpson, Wayne. “Income Maintenance, Work Effort and the Canadian Mincome Experiment.” Economic Council of Canada, Ottawa, 1991.

Hum, Derek, Simpson, Wayne. “Economic Response to a Guaranteed Annual Income: Experience from Canada and the United States.” Journal of Labour Economics, vol. 11, no. 1, 1993, pp. 263-294.

Hum, Derek, Laub, Michael, Powell, Brian. “The Objectives and Design of the Manitoba Annual Income Experiment.” Technical Report No. 1 of the Manitoba Basic Annual Income Experiment.University of Manitoba, Institute for Social and Economics Research. 1979, Winnipeg. DOI: 10.5203/FK2/XAGGJT

Kassam, Ashifa. “Ontario Plans to Launch Universal Basic Income Trial Run This Summer.” The Guardian, 25 April 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/apr/24/canada-basic-income-trial-ontario-summer

Mason, JW. “What Recovery? The Case for Continued Expansionary Policy at the Fed” Roosevelt Institute. New York, NY, 2017. www.rooseveltinstitute.org/what-recovery/

McFarland, Kate. “Overview of Current Basic Income Related Experiments (October 2017).”Basic Income Earth Network (BIEN), 19 October 2017. http://basicincome.org/news/2017/10/overview-of-current-basic-income-related-experiments-october-2017/#kenya

Nikiforos, Michalis, Steinbaum, Marshall, Zezza, Gennaro. “Modelling the Macroeconomic Effects of a Universal Basic Income.” Roosevelt Institute. New York, NY, 2017. http://rooseveltinstitute.org/modeling-macroeconomic-effects-ubi/

Osterkamp, Rigmar. “The Basic Income Grant Pilot Project in Namibia: A Critical Assessment.” Basic Income Studies, vol. 8, no. 1, 2013, pp. 71-91. DOI: 10.1515/bis-2012-0007

Palley, Thomas. “America’s Exhausted Paradigm: Macroeconomic Causes of the Financial Crisis and Great Recession” in After the Great Recession: The Struggle for Economic Recovery and Growth, edited by Cynamon, Barry, Fazzari, Steven. Cambridge, New York, 2013

Salahi-Isfahani, Djavad. “Energy Subsidy Reform in Iran” in The Middle East Economics in Times of Transition, edited by Diwan, Ishac, Galal, Ahmed. Palgrave Macmillan, UK, 2016.

Salehi-Isfahani, Djavad, Mostafavi-Dehzooei, Mohammad. “Cash Transfers and Labour Supply: Evidence From a Large-Scale Program in Iran.” Economic Research Forum, Working Paper No. 1090, 2017, http://erf.org.eg/publications/cash-transfers-and-labor-supply-evidence-from-a-large-scale-program-in-iran/.

Simpson, Wayne, Mason, Greg, Godwin, Ryan. “The Manitoba Income Experiment: Lessons Learned 40 Years Later.” Canadian Public Policy, vol. 43, no. 1, 2017, pp. 85-104.

Soleimaninejadian, Pouneh, Yang, Chengyu. “Effects of Subsidy Reform on Consumption and Income Inequalities in Iran.” International Journal of Economics and Management Engineering, vol. 10, no. 12, 2016, pp. 2596-2605.

Special Senate Committee on Poverty, “Poverty in Canada: Report of the Special Senate Committee on Poverty.” Information Canada, Ottawa 1971.

Tabatabai, Hamid. “The Basic Income Road to Reforming Iran’s Price Subsidies.” Basic Income Studies, vol. 6, no. 1, 2010, pp. 1-24.

“TV Address by President Ahmadinejad.” Tehran Times, June 25, 2008. http://www.tehrantimes.com/news/171601/Ahmadinejad-elaborates-on-economic-reform-plan

Widerquist, Karl. “A Failure to Communicate: What (If Anything) Can We Learn From the Negative Income Tax Experiments?” The Journal of Socio-Economics, vol. 34, 2005, pp.49-81

Y Combinator Research. “Basic Income Project Proposal: Overview for Comments and Feedback.” September 2017. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/599c23b2e6f2e1aeb8d35ec6/t/59c3188c4c326da3497c355f/1505958039366/YCR-Basic-Income-Proposal.pdf

Editor: Eric Witmer

Photo Courtesy of The Metric