Universal Basic Income: A Pandemic Based Reassessment

By Beulah Samuel-Ogbu

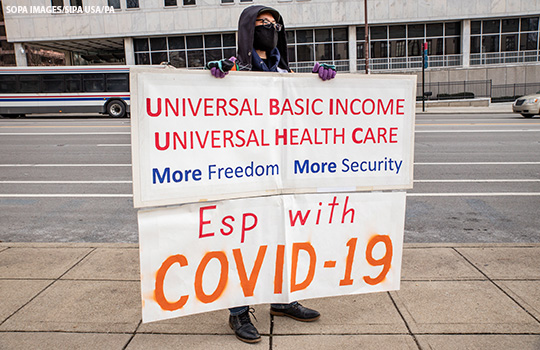

Economic consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic have led to a reassessment of Universal Basic Income and a reconsideration of Universal Basic Services.

Covid-19 poses a significant threat to the global economy. To control its spread, governments worldwide imposed isolation and quarantine policies. These strategies, although necessary to mitigate health risks, had consequential impact on the global economy. The economic shock is predicted to exceed that of the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 (Johnson et al.).The World Bank’s semi-annual Global Economic Prospects report calculated that in 2020 the world economy shrank by 4.3%, a setback only matched by The Great Depression of the 1930s and the two World Wars. Yet, this calculation still understates the actual pandemic losses. The report did not articulate what the global economy would have looked like without the global pandemic. The World Bank, when it was oblivious to the threat of Covid-19, predicted in 2020, global GDP would expand by 2.5% to $86 trillion. Covid caused a shortfall of 6.6%, which is equivalent to about $5.6 trillion (The Economist).

Lockdown measures, such as self-quarantining, restrictions on mobility and widespread closures of businesses, contributed considerably to the economic descent. These measures have had a consequential effect on consumer behaviour (Witteveen and Velthorst). Businesses have folded, and employees made redundant. The sectors most affected are tourism, culture, education, health, trade, and the oil industry (Sułkowski). The pandemic has severely affected the airline industry due to the travel restrictions. Airports Council International (ACI) World, at the start of the pandemic, determined there could be a 4.6 billion reduction of passengers in 2020. The Council also predicted a dramatic fall in revenue of around $97 billion for 2020 (Roy). Covid-19 contributed to the rapid fall in oil prices and decreased prices for oil products in the international market. This resulted in a loss in revenue for countries dependent on oil for trade (Roy). At the beginning of the pandemic, the Covid-19 outbreak in China caused major disruption to the Global Supply Chain. “Companies across the world, irrespective of size, that are dependent upon inputs from China have started experiencing contractions in production”(Baldwin et al. 45). Supply chain disruptions continue to plague the world. The pandemic has greatly distorted usual consumption patterns and created market anomalies. The aftershock of Covid-19 will cause the real national income to fall. In the UK, public sector net borrowing is predicted to rise to about 14 per cent of national income. This policy would result in the highest annual deficit since the second world war (Prabhakar). The global economy needs a solution for relieving the traumatic effects of Covid-19. Universal Basic Income has been proposed as a credible solution to the conundrum.

Universal Basic Income (UBI) is a concept often associated with alleviating financial hardships amongst the most vulnerable in a population. UBI also ensures income security to deal with redundancy amongst the threat of certain jobs being replaced by the onset of the rise of technological innovation. Andrew Yang, the 2020 Democratic United States Presidential nominee hopeful, advocated for UBI to address wealth inequities (Johnson and Roberto). Critics of UBI see the program as an expensive radical experiment. It has often been referred to as a “utopian” proposal.

Critics of UBI have significantly altered their scepticism as a result of COVID-19. The economic repercussions of the pandemic in the UK have caused even critics to support an “emergency £1,000 per month, citing favourable costs – just £60bn a month- compared to the £500 bn bank bailout of 2008” (Thompson, Matthew and Heseltine Institute for Public Policy, Practice and Place). The Spanish government is reportedly considering implementing UBI as a permanent instrument to help counter the fallout of the pandemic. The British Prime Minister Boris Johnson is openly entertaining the prospect of UBI following a letter signed by over 170 MPs calling for UBI to be used to deal with the economic consequences of the pandemic (Thompson, Matthew and Heseltine Institute for Public Policy, Practice and Place). UBI is regarded as a necessary tool in combating the current health crisis and the rapidly devolving economic conditions. UBI provides a fast and effective but arguably not the most effective response to the Covid-19 crisis. Instead, Universal Basic Services provides a more interventionist and state entrepreneurial approach (Thompson, Matthew and Heseltine Institute for Public Policy, Practice and Place).

COVID-19 Pandemic and Re-evaluation of Universal Basic Income

The COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically increased discussions surrounding Universal Basic Income as a plausible public policy solution. UBI is income transferred from the state to individuals without means test or work requirements (Parijs), through distributing a regular interval of payments. Individuals who receive the payment should have the freedom to spend the money however they choose (Johnson and Roberto). In his paper Competing justifications of basic income, Philippe Van Parijs describes Universal Basic Income as a “beautifully, disarmingly simple idea. Under a variety of names – state bonus and social credit, social wage and social dividend, guaranteed income and citizen’s wage, citizenship income and demogrant, existence income and universal grant, it has been vindicated using the widest range of arguments: liberty and equality, efficiency and community, common ownership of the Earth and equal sharing in the benefits of technical progress, the flexibility of the labour market and the dignity of the poor, the fight against unemployment and against inhumane working conditions, against the desertification of the countryside and against interregional inequalities, the viability of cooperatives and the promotion of adult education, autonomy from bosses, husbands and bureaucrats, have all been invoked in favour of what will here be called, in agreement with prevailing English usage, a basic income”(Parijs 3). Rooted in liberal thought, UBI is seen as a means of providing freedom for all. UBI is also seen as a means of dealing with the threat of automation. “Automation is thought to threaten all types of jobs in the economy, from the use of robots to perform routine tasks on factory production lines to using computer algorithms to provide professional services such as legal advice. Although automation might displace jobs, proponents argue, it may also create surplus within the economy. The idea then is to spread this surplus throughout society through a universal basic income”(Prabhakar).

Source: Thompson, Matthew, and Heseltine Institute for Public Policy, Practice and Place. Universal Basic Income: A Necessary but Not Sufficient Response to Crisis. University of Liverpool Repository, 2020. DOI.org (Datacite), https://doi.org/10.17638/03088038.

Guaranteed minimum income systems already exist, such as the UK’s social security, the Netherlands’ bijstand and France’s revenu minimum d’insertion. However, these systems are inherently different from Universal Basic Income as they remain strongly conditional and rely on an individual’s willingness to work (Parijs 4). Before the pandemic, several nations, Brazil, Canada, Finland, India, Kenya, and Switzerland, considered introducing UBI. Alaska, a conservative-leaning state of the United States, has implemented UBI since the 1980s. Oil revenues supplement this program, significantly reducing the rate of poverty among indigenous people. Despite the success in Alaska, the red blooded capitalist society of the United States has often viewed UBI in a negative light as an ‘utopian’ proposal (Johnson and Roberto). Even in the UK, which has a comprehensive social security system, sceptics tend to hold two main objections against UBI. One objection is its adequacy in tackling poverty and inequity (Prabhakar). Implementing a successful UBI is viewed as an expensive endeavour. Martinelli conducted a policy simulation for the UK and argued “an affordable UBI is inadequate, and an adequate UBI is unaffordable”(Prabhakar). A second objection points out the alternative policies that better address income inequality and poverty. “What is perhaps most frustrating for those who see little attraction in pursuing a basic income is that, while it is part of a spectrum of social protection and social security measures, giving it pre-eminence diverts from the task of promoting more feasible and sensible reforms. There is a desperate need for more investment in human capital for the least advantaged and for more equal opportunities for all” (Prabhakar)

The first objection in regards to affordability has significantly changed during the global pandemic. The global pandemic has even caused sceptics to see the need for UBI as an immediate relief for the traumatic aftershock of the pandemic. Universal Basic Income (UBI) could provide faster and more effective income relief than existing welfare measures. Regular payments to individuals can address the immediate needs of redundant employees, the closing of businesses, increased hardships and falling incomes. A stimulus package is a key component in easing the trauma of the pandemic in securing financial security for households. It “could also potentially plug the gap in the current government income support schemes (Thompson, Matthew and Heseltine Institute for Public Policy, Practice and Place).

The presence of UBI in American society has shifted. Before the pandemic, the program would have been viewed as a radical social experiment. The former conservative US President signed a bill promising $2 trillion worth of federal government assistance to households and businesses. The Federal government distributed $1200 per person per month for one year(Prabhakar). The UK government Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme provides a taxable grant for employers for furloughed employees who could receive 80 per cent of the wages (up to £2,500 a month).

These programmes show a shift in attitude towards UBI. In the past, UBI was associated with reducing poverty in low- and middle-income countries. Covid-19 has presented a strong argument for UBI to exist in a wealthy country as well. UBI has become a measure in preventing financial collapse for many middle-class families. The global pandemic has conjured era-defining levels of unemployment, and underemployment has greatly overwhelmed existing relief infrastructure (Johnson and Roberto). “A guaranteed source of revenue would provide the unemployed and underemployed with basic support while providing a safety net (should employment status change) for those with greater income to be less cautious about spending. This would lead to increased consumer confidence and spending”(Johnson and Roberto).

“At first sight, Covid-19 seems to have enlarged the realm of the possible for public spending. The immediate priority is to provide emergency help, and this has entailed mass state spending. One might claim that previous ideas about what is unaffordable no longer hold. According to this argument, the coronavirus crisis has shown the extent to which government spending is driven by political choices. A universal basic income might therefore be deemed to be affordable”(Prabhakar).

Universal Basic Income vs. Universal Basic Services

Besides the affordability of implementing UBI, another objection to the program questions whether UBI is the best method of addressing inequity. UBI is a fast and effective means of providing income support, but UBI may be harmful as an economic stimulus package during the pandemic. Eventually, implementing UBI would make it hard to find a balance between creating an affordable program and delivering diverse policy objectives such as empowering workers. Simplifying UBI could pose health risks if installed too hastily during the pandemic as encouraging people to start spending too soon could cause individuals to increase exposure to COVID-19 (Thompson, Matthew and Heseltine Institute for Public Policy, Practice and Place). Another issue with UBI is a Universal approach to dealing with economic stimulus may be unable to fulfil the needs of low-income households. “Research has shown that low paid individuals are among the worst hit by the pandemic. One-third of employees who reside at the bottom tenth earnings distribution work in sectors that have shut down. In comparison with the 5 percent of those in the top tenth of earning distribution. UBI also does not consider that poorer and richer households have different habits when spending their income” (Prabhakar). A significant percentage of income is spent on essential items for poor households, more so than richer households. “On average, the poorest fifth of households spend around 55 per cent of their budgets on essential items, while the richest fifth spent around 39 per cent. This pattern is reversed for items that have been affected by social distancing measures such as travel, leisure or eating out”(Prabhakar).

UBS deems that basic needs which are universal and necessary for human flourishing such as education, access to information, shelters, health, nutrition, and mobility, are too important to be left to the whims of the markets.

UBI is a necessary step for dealing with the economic fallout of the Covid-19 pandemic but not a sufficient response to the crisis. “UBI alone cannot bring about the revaluation of key worker roles, particularly care work; fails to address the structural roots of its target problems; and acts as a subsidy for asset owners, especially tech giants, without reforming the tax system required to fund UBI in the first place” (Thompson, Matthew and Heseltine Institute for Public Policy, Practice and Place). Poor households may benefit more from a targeted rather than a universal payment system. Sceptics of UBI have argued Universal Basic Services is a better alternative for dealing with poverty. (Prabhakar). Universal Basic Services (UBS) is a system which safeguards and develops existing public service provisions (Gough). “A core distinction between UBI and UBS concerns fungibility. The fungibility of money means that government money transfers permit people to spend income on whatever they want. Public services are not fungible but deliver specific activities or provisions” (Gough). UBS deems that basic needs which are universal and necessary for human flourishing such as education, access to information, shelters, health, nutrition, and mobility, are too important to be left to the whims of the markets. These services should be directly funded through public investment (Thompson, Matthew and Heseltine Institute for Public Policy, Practice and Place). “UBS avoids many of the problems associated with the market that UBI perpetuates (Lombardozzi and Pitts, 2019). UBS is a more direct form of UBI – a ‘social wage’ that cuts out the middleman and saves people money otherwise spent on essentials. Whereas UBI atomises and privatises, UBS is ‘prosocial’ in that it strengthens the ties of reciprocity, solidarity, and sociability that help bind society into a functional and cohesive whole. By pooling resources and governing shared public goods as commons, UBS would enhance social citizenship, increase interaction, and raise trust in society. “UBS brings the ‘hidden abode’ of production out into the visible public sphere through provision of childcare, adult, and social care. UBI may offer financial support for people to continue doing the socially valuable yet undervalued work of caring for children, the elderly and vulnerable, as well as domestic labour in the home and volunteering in the community – work often done by women. But it does not necessarily lead to greater gender equality, more equitable divisions of labour or a revaluation of paid and unpaid roles – just as it cannot by itself generate new jobs. UBS, though, does create new employment. And it provides the material foundations for the structural revaluation of work in society – as highlighted by the newfound respect for key workers during this pandemic – in ways UBI only formally could.”(Thompson, Matthew and Heseltine Institute for Public Policy, Practice and Place).

UBI is an effective measure in dealing with the immediate issues of the Covid-19 pandemic, such as stimulating consumption. However, it is not a long-term solution. UBI is unable to tackle the direct issues hindering the prosperity of low-income households. A Universal payment system may direct funds away from services towards wallets without targeting the individuals’ needs and the problems to human flourishing which the pandemic has obstructed.

Getting to UBI and UBS

Covid-19 has significantly changed perceptions of Universal Basic Income. Before the pandemic, UBI would have been a means of tackling income inequality and poverty in low- and middle-income countries. However, the prospect of an economic crisis surpassing the global financial crisis of 2008 has caused critics of UBI to reconsider their scepticism. Regular income payments may become a vital step in mitigating the economic damage of the pandemic. Lockdown measures to quell the spread of the virus, have consequentially led to era-defining redundancies, and closing of businesses. UBI has become a credible solution to this problem. The pandemic has also highlighted other forms of public spending which are better solutions in response to the aftermath of the pandemic. Rich and poor households have different spending habits and have been impacted by the pandemic differently. Universal Basic Services may be a better tool and a targeted approach in dealing with the aspect of human prosperity negatively impacted by the pandemic.

Bibliography

Baldwin, Richard E., et al. Economics in the Time of COVID-19. CEPR Press, 2020.

Gough, Ian. “The Case for Universal Basic Services.” LSE Public Policy Review, vol. 1, no. 2, Dec. 2020, p. 6. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.31389/lseppr.12.

Johnson, Andrew F., and Katherine J. Roberto. “The COVID‐19 Pandemic: Time for a Universal Basic Income?” Public Administration and Development, vol. 40, no. 4, Oct. 2020, pp. 232–35. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.1891.

Johnson, Matthew Thomas, et al. “Mitigating Social and Economic Sources of Trauma: The Need for Universal Basic Income during the Coronavirus Pandemic.” Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, vol. 12, no. S1, Aug. 2020, pp. S191–92. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000739.

Parijs, Philippe Van, editor. Arguing for Basic Income: Ethical Foundations For A Radical Reform. Verso Books, 1992.

Prabhakar, Rajiv. “Universal Basic Income and Covid‐19.” IPPR Progressive Review, vol. 27, no. 1, June 2020, pp. 105–13. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1111/newe.12198.

Roy, Shohini. ECONOMIC IMPACT OF COVID-19 PANDEMIC. 2020, p. 20.

Sułkowski, Łukasz. “Covid-19 Pandemic; Recession, Virtual Revolution Leading to De-Globalization?” Journal of Intercultural Management, vol. 12, no. 1, Mar. 2020, pp. 1–11. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.2478/joim-2020-0029.

The Economist. “What Is the Economic Cost of Covid-19?” The Economist, Jan. 2021. The Economist, https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2021/01/09/what-is-the-economic-cost-of-covid-19.

Thompson, Matthew, and Heseltine Institute for Public Policy, Practice and Place. Universal Basic Income: A Necessary but Not Sufficient Response to Crisis. University of Liverpool Repository, 2020. DOI.org (Datacite), https://doi.org/10.17638/03088038.

Witteveen, Dirk, and Eva Velthorst. “Economic Hardship and Mental Health Complaints during COVID-19.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 117, no. 44, Nov. 2020, pp. 27277–84. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2009609117.

Photo: SIPA USA/PA Images