The EU Taxonomy

By Sarah Ahmad

Good Start but Could Be Better

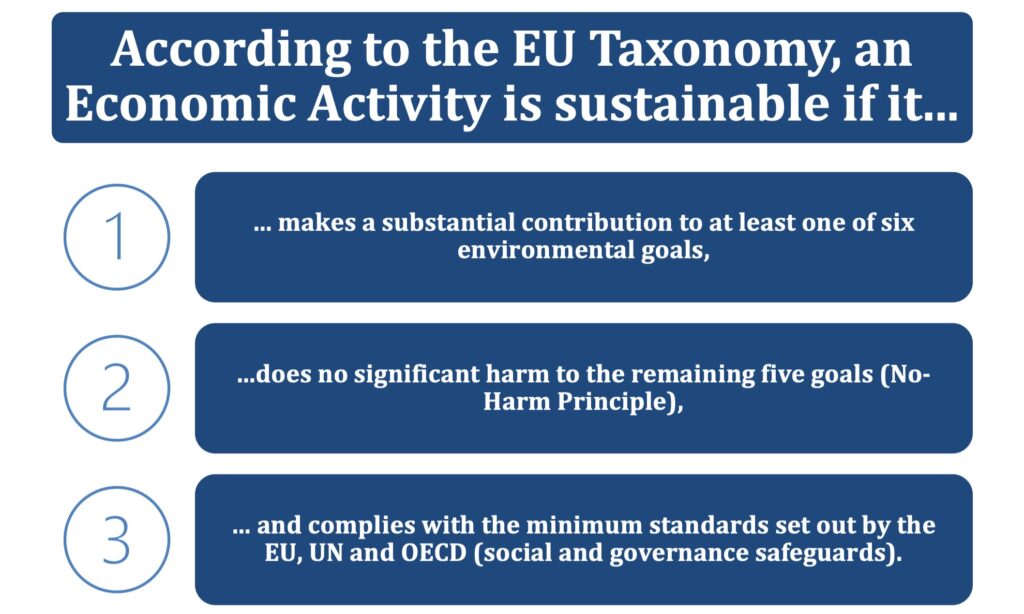

In June 2020, the European Union published Regulation (EU) 2020/852 “on the establishment of a framework to facilitate sustainable investment” and amending Regulation (EU) 2019/2088 (hereafter ‘EU Taxonomy’). In essence, the EU Taxonomy requires economic activities to (i) contribute to at least one of six identified environmental goals whilst (ii) not violate the remaining five objectives, and (iii) to comply with the minimum standards set out by the EU, UN, and OECD. As a classification tool to define which activities are sustainable and ‘green’, the EU Taxonomy is crucial for the European Union to become climate neutral by 2050 – an endeavor that will require a minimum of €1tn of sustainable investment from both public and private investors within the next decade.

Having entered into force more than a year ago (on 12th July 2020), the EU Taxonomy has sparked immense controversy and debate amongst EU Member States, investors and industry-leaders. Whilst the EU Taxonomy prima facie appears to be simple and comprehensive, upon closer inspection the presented framework turns out to be riddled with many indeterminacies and sets unclear thresholds, thereby undermining the effectiveness of the legislative framework and jeopardizing the European Union’s path to climate neutrality. What legislators have forgotten is that achieving ‘climate-neutrality’ is not as neutral as the label promises. In reality, the European Union’s energy and climate goals are heavily politicized and require major concessions from all Member States. Thus: (i) the EU Taxonomy fails to consider the economic, environmental, and socio-political heterogeneity of all Member States, which have different needs and views on what ‘becoming climate neutral’ ought to entail. Some Member States still generate most of their energy through nuclear plants or fossil fuels and are thus both unwilling and unable to implement the new guidelines as quickly and extensively as the EU Taxonomy demands. This problem is further exacerbated by unclear emission thresholds and disputed areas of application. Thus, the EU Taxonomy – though a commendable aspiration and useful tool to achieving climate neutrality – needs to be revisited and reconceptualized for the European Union to reach its energy and climate goals. Constant disputes and debates amongst Member States have delayed the implementation of key parts of the EU Taxonomy demonstrating the EU Taxonomy in its current form is deeply problematic.

I. What the EU Taxonomy Proposes: Scope and Application of the EU Taxonomy

The EU Taxonomy establishes a conceptual and doctrinal framework designed to ‘facilitate sustainable investment’, thereby setting common standards in what constitutes ‘green’ financial reporting and services. The framework applies to both private and public investments and Recital 54 of the Taxonomy Regulation defines sustainable economic activities. The EU Taxonomy therewith harmonizes the criteria for sustainable investment on an EU Level. Since Art 114 TFEU applies to such harmonization measures, the EU Taxonomy is binding on and directly applicable for all Member States. No further implementing domestic legislation is needed for the EU Taxonomy to take effect and to comply with the cardinal principles of subsidiarity and proportionality in EU Law.

In this context, it should be emphasized, although the European Union’s environmental policy was clearly influenced by international agreements and the “Do no significant harm” criterion is based on international environmental law, the EU Taxonomy currently applies only to the European Union and not to activities outside the Union. Yet, there is an undeniable overlap between European environmental law and policies and international law, as all EU Member States are bound by international law and the European Union party to most international environmental agreements concluded over the last decades. This ‘hierarchy’ and interconnectedness of legal systems gives the EU Taxonomy the potential to influence sustainable finance policies all over the world.

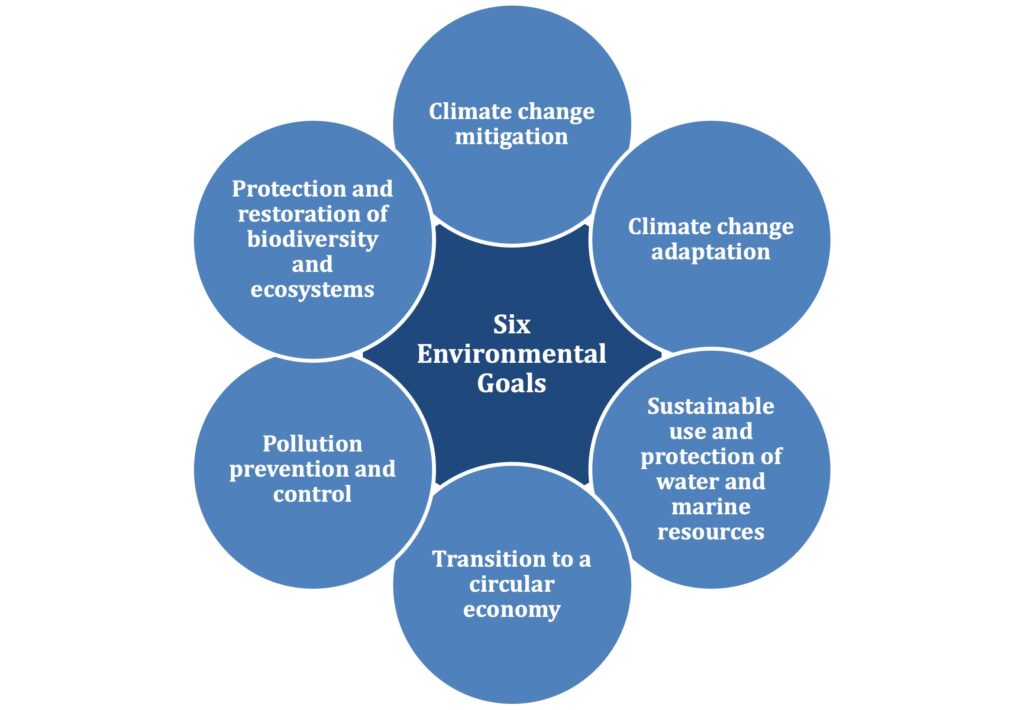

The EU Taxonomy stipulates that for an economic activity to be sustainable, it must (i) substantially contribute to one of six environmental objectives, (ii) do no harm to the other five objectives and (iii) meet international social and governance safeguards (see graphic below). In classifying economic activities, however, the EU Taxonomy does not take a binary (“sustainable or not”) approach. Rather, it includes (i) green activities contributing to climate change mitigation, (ii) enabling activities which facilitate other economic activities and emission reductions in other sectors (these are already low carbon and further contribute to the European Union reaching climate neutrality by 2050) and (iii) transitioning activities that need substantial work and revision to become climate neutral. In all three types of activities there are additional minimum standards of social and environmental protection embedded.

The EU Taxonomy reflects the rise of ‘sustainable finance’ since 2009. The European Commission defines sustainable finance as ‘the process of taking due account of environmental and social considerations in investment decision-making, leading to increased investments in longer-term and sustainable activities’ (European Commission, 2018). Whilst Lucarelli et al point out the Taxonomy framework was undoubtedly influenced by scientific literature and research, it would be wrong to consider the EU Taxonomy as inherently ‘neutral’ or ‘objective’ (Lucarelli, 2020). Rather, the EU Taxonomy is a multifaceted and heavily politicized framework that determines the future of EU finance. Thus, the EU Commission established a Technical Expert Group with industry, government, academic and civil society experts to depoliticize the process of developing the Taxonomy – an attempt that lamentably failed, as subsequent analysis will show.

The Taxonomy stipulates investment funds and large public interest entities must disclose whether and to what extent their economic activities comply with the EU Taxonomy’s definition of sustainability as part of their annual non-financial reporting obligations. By imposing additional compliance requirements on investors and financial actors, the EU Taxonomy will ‘push industry to make environmentally rational choices in terms of corporate strategy’. These new disclosure requirements apply to companies required to provide a non-financial statement under Art 29 of the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD). This applies to companies with more than 500 employees, including insurance companies, banks and listed companies. It also covers public entities ‘governed by law of a Member State’ (Art 2 NFRD). That said, voluntary disclosure for small companies and other entities not covered by the NFRD is explicitly encouraged by the European Commission. Affected firms and entities are obliged to disclose information related to (i) environmental matters, (ii) respect for human rights, (iii) treatment of employees, (iv) diversity on company boards and (v) anti-corruption and bribery.

These firms will need to make informed choices on their investments and will increasingly reject non-Taxonomy compliant investments. This, in turn, will safeguard and extend the influence and relevance of the EU Taxonomy. As Piebalgs and Jones predict, the EU Taxonomy ‘will no doubt increasingly become the baseline for many legislative provisions and requirements in other areas’ (Piebalgs and Jones, p.3). Given the complexity of the Taxonomy regulation, affected investors will have to be unusally diligent to assure compliance with the Taxonomy.

II. EU Taxonomy in Context: EU’s path to climate-neutrality

The EU Taxonomy forms part of wider efforts by the European Union to reach climate neutrality. Prior to the implementation of the Taxonomy, all policy proposals by the Commission had to comply with environmental protection (Art 114 TFEU), but each Member State set its own standards and classification systems for sustainability. This led to a lack of transparency and comparability between systems within the European Union. As Alessi et al rightly argued, ‘the absence of commonly agreed principles and metrics for assessing if economic activities are environmentally sustainable hindered the redirection of capital towards more sustainable economic activities’ (Alessi et al, 2019).[1] By standardizing the criteria for sustainability and establishing a common definition of ‘green finance’, the European Union aims to take effective steps to secure enough funding to address the estimated investment gap of approximately $27 trillion (IRENA, 2019) to reach its climate aims by 2050. The EU Taxonomy must thus be viewed together with the EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) and the Low Carbon Benchmarks Regulation, two other regulatory frameworks to implement sustainable finance. This contextualization is key to understanding the broader political, legal, and environmental factors in which the EU Taxonomy operates and to understand the problems the EU Taxonomy currently faces and to truly evaluate the current state of the EU Taxonomy.

III. Evaluation of the EU Taxonomy

Strengths

As the European Union has common climate goals and pursues common environmental policy, it is only logical that all Member States are bound by the same legislative and conceptual framework to reach such goals. However, this had not been the case before the EU Taxonomy was implemented. A multitude of varying standards and definitions of sustainability seriously undermined common climate goals and the transition to a climate-neutral economy. Having a common classification tool across all EU Member States not only makes environmentally sustainable investment comparable, but also prevents “greenwashing” and other forms of deceit. By requiring large public entities and investment funds to disclose their Taxonomy-compliance, the EU Taxonomy sets an end to the voluntary initiatives in some Member States and enforces regulatory environmental standards more effectively and rigidly. This is to be welcomed, as mandatory disclosure will positively contribute to the EU’s climate goals. Dr. Richard Teichmann, CEO at Teichmann & Compagnons Property Networks GmbH, has thus praised the EU Taxonomy as a ‘ game changer for the market’ (DGNB, p.11) and Leoni Gros from Berlin Hyp AG stated that ‘with the Taxonomy a way is opened for the transition of the economy and the financial sector’ (DNGB, p.24).

Financial investors will greatly benefit from such standardized criteria for sustainable investments, as they will have to adapt their practices to a single set of regulations, which reduces costs and makes it easier for them to comply with all environmental regulations. Thus, the EU Taxonomy ‘enhances investor confidence and awareness of the environmental impact of financial products (Gortsos, 2020).[2] By dividing activities in ‘green’, ‘enabling’ and ‘transitioning’, the EU Taxonomy also acknowledges the difficulties of transitioning to climate neutrality. Some industries will need significant time and (financial) support to successfully reduce emissions and develop Taxonomy-compliant activities. The EU Taxonomy must therefore address the ‘dynamic character of the transition’ and enable a gradual transitioning with varying thresholds for emission-intensive transition sectors (OECD, 2020).

Weaknesses

Arguably, the biggest weakness of the EU Taxonomy lies in the industry-specific emission thresholds the Taxonomy stipulates. Setting adequate thresholds in each sector is undeniably difficult: As Schütze and Stede rightly argue, if thresholds are too low, this causes ‘carbon lock-in effects’ that entrench ‘emission-intensive technologies and fossil infrastructure for many decades’ (Schütze and Stede, 2020). If thresholds are too strict, however, this causes rising financing costs for investments, as fewer investments are classified as ‘sustainable’. Looking at nuclear energy, the automotive sector, and the buildings sector, current thresholds are often too vague and incompatible with climate neutrality.

The inclusion of nuclear energy into the Taxonomy was highly disputed and decided only in April 2021. Different EU Member States have opposing views on nuclear energy: Whilst countries such as Belgium, Bulgaria, Finland, France, Hungary, and Romania advocate for the inclusion of nuclear energy, Germany and Austria are strictly against this. The polarization of EU Member States arises because nuclear energy, though low in carbon emissions, is regarded as dangerous, having the potential to destroy the planet and human species. Some Member States view the inclusion of nuclear energy as retrograde and in violation of the ‘no harm principle’ of the Taxonomy whilst others generate most electricity through nuclear energy and would thus welcome the inclusion into the Taxonomy. This example illustrates the politicization of the EU Taxonomy. The term “climate neutrality” appears to be neutral, but in reality, a variety of economic, political and social considerations and concerns are inherently tied to it. This knotty problem, it seems, has largely been forgotten. By establishing EU-wide thresholds and guidelines, the situation in the individual Member States is neglected and not enough compensation and incentives offered to States that still depend either on high-emission activities or on nuclear energy.

In the automotive sector, by contrast, strict thresholds have been implemented: Newly produced passenger cars and light commercial vehicles may not emit more than 50 grams of CO2 per kilometer until 2025. From 2026 onwards, emissions must be reduced to zero. Whilst this may seem unrealistic at first sight, the automotive sector is heavily subsidized in the European Union and environmental agencies and NGOs therefore support such a rigid threshold. The automotive industry, by contrast, demands an extension of the transition period and further financial support to meet the stipulated regulations. Other sectors such as aviation have not been included yet, as the EU Taxonomy currently covers only approximately 80% of all emissions in Europe. In the buildings sector, on the other hand, the EU Taxonomy two different thresholds, distinguishing between (i) renovation projects as stipulated by the EU Directive on the Energy Performance of Buildings (EPBD) and (ii) the energy-efficient refurbishment of existing buildings that reduces the primary energy requirement by at least 30%. The annual primary energy demand for newly constructed buildings must be 20% below the national standard for Nearly Zero activities, which sets sector-specific benchmarks as threshold.[3] Scientists and industry representatives alike have criticized these thresholds arguing that thresholds must be increased for the industry to meet its climate goals. Accordingly, Schütze and Stede conclude ‘the stringency of the respective threshold is an important factor determining the level of ambition to achieve climate neutrality’. In its current form, the EU Taxonomy sets controversial thresholds that are either unrealistic according to industry representatives or not stringent enough for industries to become climate neutral.

To conclude this section, the current criteria and thresholds are largely insufficient for the European Union to meet its climate and energy goals. Thresholds should also distinguish between new investments and existing arrangements to prevent carbon lock-in effects and to foster an environment of effective compliance (Schütze et al, 2020). This means further incentives to decarbonize the economy are needed. Such incentives must be accompanied by a profound information campaign that raises investors’ awareness of the EU Taxonomy and clearly shows them how to best avoid greenhouse gas emissions, thereby meeting the Taxonomy’s regulatory requirements. Ultimately, however, Schütze and Stede might be right in arguing a much stricter, categorical approach to classifying economic activities is needed: maybe it is time to rigidly point out ‘low-emissions activities and high-emission activities that are inherently incompatible with a low-carbon future’ and to take action to restrict the latter. The Taxonomy has been widely criticised for ignoring scientific advice and setting arbitrary emission thresholds. In its current form, the EU Taxonomy fails to defeat concerns that these politicized regulatory standards actually enable (rather than prevent) greenwashing.

Interest by private investors in ESG has been steadily increasing over the years, with Germany experiencing a 96% increase in sustainable investments in 2019 (as compared to 2018) (Schütze and Stede, 2010). Yet, prior to the implementation of the EU Taxonomy, different standards and metrics made it very difficult for investors to compare green investments. The Taxonomy operates on two different levels, the project level and the firm level. Both significantly impact a firm’s capital and costs. Whilst the project level regards the planning and realization of new investments (emission-thresholds vary and depend on the industry), the firm level evaluates a company based on its sales and expenses. The EU Taxonomy embeds enhanced human rights and social governance standards, as required by the EU, UN, OESCD. At the moment, the firm size determines whether sustainability disclosure is voluntary or, if a firm is subject to the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (Directive 2014/95), mandatory. Unfortunately, this disclosure requirement is not clear enough in the Taxonomy’s current form, as current regulations do not explain the extent and scope of the disclosure requirement and whether it applies to whole supply chains or individual companies. In its Action Plan on Sustainable Finance, the European Union highlights the importance of sustainable investments by the private sector to alleviate and close the predicted investment gap. Yet, despite the reliance on the private sector, policy-makers insufficiently consulted with industry-leaders and private experts. Rather, the Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance (TEG) developed the methodology and screening criteria of today’s Taxonomy. This resulted not only in unrealistic thresholds and harsh critique from investors and various industries, but also jeopardized the success of the European Union’s path to climate neutrality. Eurosif, a European association for the promotion and advancement of sustainable and responsible investment across Europe, has thus claimed that ‘it is unlikely that alignment with the Taxonomy will be a material factor informing investment decisions in the near future’. Similarly, Neste Analysis has titled that ‘the objective [of the EU Taxonomy] is good and welcome, but the preparation of the actual Taxonomy has taken a wrong track’. Thus, policy-makers need to revise current thresholds in consultation with industry-leaders and set more incentives to convince investors of this legislative and conceptual regulatory framework.

IV. The EU Taxonomy – the future ‘blueprint for a global standard for sustainable economic activities’

Despite all these shortcomings and flaws of the current Taxonomy framework, the EU Taxonomy has been praised as a ‘key milestone in defining legally sustainable activities’ (Gortsos, 2020) and a ‘blueprint for a global standard for sustainable economic activities’ (Schütze and Stede, 2020). This praise does justice to the immense potential of the EU Taxonomy and the global significance and impact it might have in the future: Even though the EU Taxonomy is only binding in the European Union, businesses and investors all over the world will have to adopt their economic activities to make them Taxonomy-compliant if they wish to continue to invest in and trade with the European Union. Thus, the scope and application of the EU Taxonomy will likely amplify in the near future, so the EU will lead in global efforts on effective environmental regulation. However, significant parts of the EU Taxonomy should be revisited for this legislative framework to reach its fullest potential. Improvements include a revision of sector-specific thresholds, the development of a fairer strategy for all Member States and enhanced communication and cooperation with affected businesses and investors. At the same time, law and policy-makers must not forget the science on climate change is evolving. Thus, the EU Taxonomy must reflect new scientific developments and should be updated regularly to address new knowledge and scientific predictions. Only so can the EU Taxonomy become a truly effective tool to mitigate climate change and promote sustainable investment, thereby setting a global benchmark for non-European jurisdictions which create their own taxonomies.

In light of the (anticipated) broad scope of the EU Taxonomy, there is speculation whether the United States would adopt a similar regulatory regime in the near future. Whilst an international taxonomy harmonization would make compliance with environmental standards easier and less expensive for businesses, the United States traditionally prefers a laissez-faire approach to regulation: little state intervention and the promotion of a free and competitive self-regulating market. It should also be remembered the EU Taxonomy forms part of wider efforts and strategic plans to achieve climate-neutrality within the EU. The United States currently lacks similar ambitions or political unity to promote ‘green finance’. That said, the United States will have to divert from its laissez-faire approach if the new EU-US Trade and Technology Council is to be an effective and fruitful collaboration between both partners. If the United States adopts a similar framework, scientific findings should be prioiritized over politics so the European Union’s mistakes are not repeated.

Bibliography:

Primary Source:

Directive 2013/34/EU https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32013L0034 as amended by Directive 2014/95/ https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32014L0095

Secondary Sources:

Alessi, L., Battiston, S., Melo, A.S. and Roncoroni, A., The EU Sustainability Taxonomy: a Financial Impact Assessment, EUR 29970 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2019, ISBN 978-92-76-12991-2, doi:10.2760/347810, JRC118663.

DNGB, EU TAXONOMY STUDY: Evaluating the marketreadiness of the EU taxonomy criteria for buildings, 2021.

EBI Working Paper Series; Christos V. Gortsos, ‘The Taxonomy Regulation: more important than just as an element of the Capital Market Union’, 16/12/2020.

Eurosif, The EU Taxonomy: Fostering An Honest Debate, 2021. https://www.eurosif.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/read-our-full-Position-paper.pdf

IRENA (2019), Global energy transformation: A roadmap to 2050 (2019 edition), International Renewable Energy Agency, Abu Dhabi. https://www.irena.org/publications/2019/Apr/Global-energy-transformation-A-roadmap-to-2050-2019Edition

Lucarelli, C.; Mazzoli, C.; Rancan, M.; Severini, S. Classification of Sustainable Activities: EU Taxonomy and Scientific Literature. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6460.

Teja, Natasha, ‘EU Taxonomy Regulation still has missing pieces’, International Financial Law Review ; London (May 3, 2021).

OECD (2020), “The European Union sustainable finance taxonomy”, in Developing Sustainable Finance Definitions and Taxonomies, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/5e092588-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/5e092588-en

Andris Piebalgs, Christopher Jones, ‘The Importance of the EU Taxonomy: the Example of Electricity Storage’ Policy Brief 2021/11 https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/70475/PB_2021_11-FSR.pdf?sequence=1

Schütze, Franziska; Stede, Jan; Blauert, Marc; Erdmann, Katharina (2020), ‘EU taxonomy increasing transparency of sustainable investments’, DIW Weekly Report, ISSN 2568-7697, Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung (DIW), Berlin, Vol. 10, Iss. 51, pp. 485-492