The Case of Danske Bank and Money Laundering

By Blythe Logan

In September 2018, Danske Bank went from one of the most respected European financial institutions to being implicated in what may be the world’s largest money laundering scandal. Before the controversy, Danske’s home nation of Denmark topped international transparency rankings as one of the world’s least corrupt places (Wienberg). Following the news of the money laundering scheme, Danske assigned blame to poor communication between the executive board of the bank in Copenhagen and corrupt management in the bank’s Estonian branch. Subsequently Danske introduced many new policies to improve anti-money laundering (AML) efforts in the bank (Investigations into Danske Bank’s Estonian Branch | Danske Bank). Despite these claims and endeavors to change the bank’s culture, it is likely executives in Copenhagen knew unethical behavior was taking place at the Estonian branch from 2007-2015 but chose to turn a blind eye (Coppola). Given deontological and utilitarian analyses of the case, Danske Bank’s financial decisions during the past decade can be understood as unethical.

Cleaning Dirty Money

Money laundering is the process of making money generated by criminal activity (such as drug trafficking or embezzlement), appear to come from a legitimate source. The technique gets its name from obscuring the illegal origins or “laundering” dirty money, which then becomes “clean” or legal money that can be integrated into the economy. Money laundering typically involves three steps: placement, layering and integration (Money Laundering – Financial Action Task Force (FATF)).

In the placement stage, the launderer introduces its illegal money into the financial system, often by using a technique called smurfing, which entails depositing the money in smaller sums across multiple bank accounts. This technique further disguises the source of the money from banks, financial institutions or law enforcement agencies (“Money Laundering”).

In the layering stage, the launderer shifts the money through a series of transactions and/or conversions to further conceal its source from investigators. Layering might include sending wire transfers between accounts across the globe, making property or service transactions with shell companies (inactive companies that exist only on paper and perform no real economic function besides use for launderers), and purchasing luxury goods or real estate.

In the integration stage, the launderer makes a legal transaction to secure the funds for herself in the legitimate economy, often with the sale, transfer or purchase of real estate, securities or luxury assets in the name of the launderer (Money Laundering – Financial Action Task Force (FATF)).

Money laundering can be much more complex, especially with the rise of electronic transfers and cryptocurrencies, but nearly all laundering attempts involve these three steps. Danske Bank’s scandal is linked to the Azerbaijani and Russian laundromat schemes which transfers illegally earned money by Azerbaijani and Russian criminals to offshore accounts, often in the form of weakly regulated UK-based Limited Liability Partnerships (LLP) and Scottish Limited Partnerships (SLP). These shell companies in turn transferred the money to Azerbaijani and European elites (Garside). The launderers moved the large sums of money to offshore accounts because of lower transparency standards for owners of LLPs and SLPs in the UK and other countries to open corporate bank accounts. Shifting the funds to countries where regulation is not as stringent helped the criminals further avoid being caught by regulators and auditors in Russian or Azerbaijani based banks (Garside).

Although financial institutions involved in money laundering may not have a role in the production of the illegal funds, their laundering of the funds is a crime for many reasons. If illegal money is processed easily through a particular financial institution, whether it is due to bribery or internal auditors turning a blind eye to suspicious accounts, the institution may be actively complicit with illegal activity. Such a reputation among regulators, financial intermediaries, and customers is damaging for the institution. Complicit behavior will also have macroeconomic effects on international capital flows and exchange rates (Money Laundering – Financial Action Task Force (FATF)). Although money laundering does not affect legal customers directly, it enables criminal activity to continue, which could imperil ordinary clients.

Breaking Down Danske’s involvement in Money Laundering

The scandal surrounding Danske Bank is the most significant recent instance of money laundering, with $236 billion in laundered money estimated to have passed through its Estonian branch. Large regulatory bodies as well as individual customers of the bank have questioned how much of the issue was excusable misunderstanding between the branch and Executive Board of the bank and how much was deliberate Board negligence.

Early Stages and Growth of Nonresident Business

On February 1, 2007, Danske Bank completed the acquisition of AS Sampo Bank for $4.57 billion. This purchase included a branch in Tallinn, Estonia, which would go on to function as the center of Danske’s money laundering operations (Coppola). A few months after Danske took over the branch, Russia’s central bank warned Danske that the branch was being used for dubious transactions, possibly entailing tax evasion or money laundering, on the order of billions of rubles per month (Milne and Winter). Soon after, Estonian financial regulators also criticized the bank for underestimating compliance risks and the possible problems with its know-your-customers (KYC) rules. During the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008, Danske did not devote sufficient focus in integrating AS Sampo Bank branches into the Danske Bank system. The Estonian branch remained under its own management and largely independent from operations in Danske’s headquarters in Copenhagen (Coppola). In 2008, Danske’s plans to migrate the Baltic branches onto the Danske’s main IT platform were abandoned on the grounds of cost, and those branches’ AML checks suffered as a result (Milne and Winter). Control from Copenhagen was further impaired by most of the documents at the Estonian branch being written in Estonian or Russian, a practice the branch sustained until its closure (Danish Financial Supervisory Authority).

In 2009, Thomas Borgen was appointed as Head of International Banking Activities, and much of his responsibility in that position was directly overseeing the Baltic branches. Borgen made clear in his discussion of goals for 2010 that he intended to expand the base of nonresident business, which mostly consisted of Russian and Ex-Soviet nation customers (Milne and Winter). Following this announcement, the Danske Bank Executive Board observed suspicious activity as per reports on the Estonian branch. Yet, the Board expressed indifference to the “substantial Russian deposits” as the amount of profit the Estonian branch earned from foreign accounts increased dramatically (Milne and Winter). January 25, 2010 was the first time Estonian-based media linked a particular nonresident account and currency exchange business at the Tallinn branch to a money laundering scheme (Bruun and Hjejle 42).

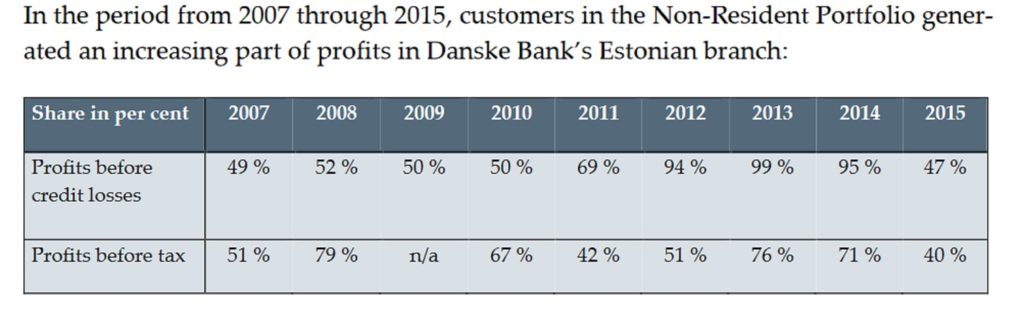

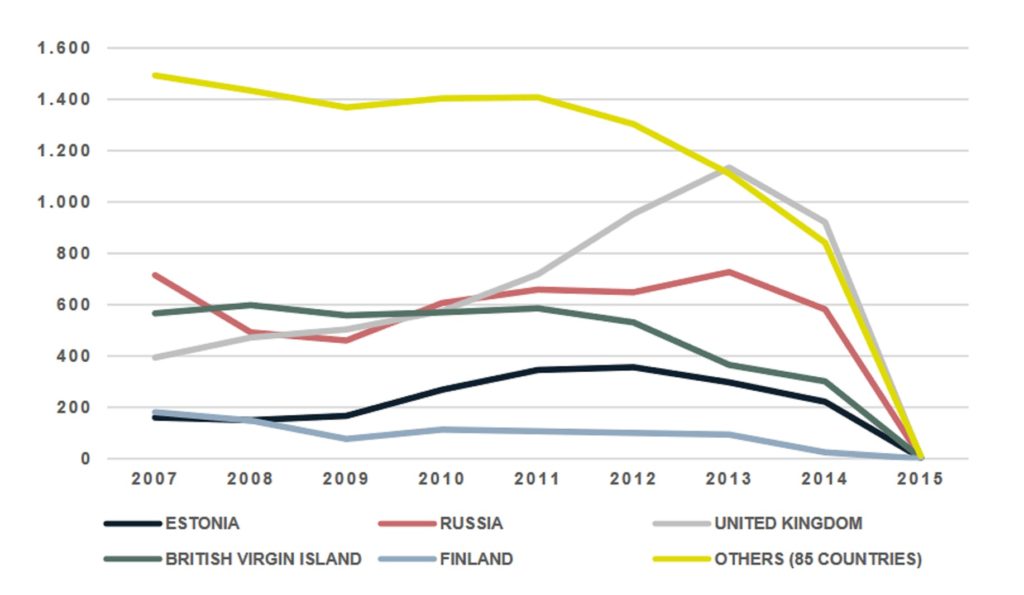

From 2010 until 2015, the Estonian branch’s nonresident portfolio grew, and from 2007 to 2013, the percent profits before credit losses of the nonresident accounts for the Estonian branch rose from 49% to 99% of the branch’s total profits (Bruun and Hjejle 26). The majority of nonresident customers were corporate entities from Russia, the UK and the British Virgin Islands (Bruun and Hjejle 23). In 2011, the Estonian branch also generated 11% of Danske’s total profits before tax, despite only making up 0.5% of the bank’s assets (Milne and Winter). In that same year, internal auditors at Danske reported less than satisfactory AML regulation at the Estonian branch to the Executive Board, and then in 2012 the Danish Financial Supervisory Authority (FSA) also notified Danske’s compliance group about its lack of improvement in risks related to AML in the Estonian branch (Bruun and Hjejle 47).

In 2012, Borgen accepted the position of CEO of Danske Bank and left his previous position as Head of International Banking Activities. In 2013, Danske’s head office had no person responsible for anti-money laundering, as required by Danish law, all year until November. JPMorgan stopped being a correspondent bank for dollars to the Estonian branch, citing concerns with non-resident customers. Despite wariness from correspondent banks like JPMorgan, Bank of America and Deutsche Bank, Borgen expressed unwillingness to scale back nonresident accounts in a 2013 meeting between the management of the Estonian branch and Danske’s head management (Milne and Winter).

The Business Banking group at Danske noted several money laundering signs in a 2013 report on the Estonian branch. Firstly, the number of transactions among nonresident accounts was much larger than normal. Secondly, the branch generated over-normal profits and demonstrated a lack of price sensitivity with certain customers. Finally, many of the branch’s customers were “so called” intermediaries in the form of non-regulated entities. The group also commented on the reputational risk associated with assisting “capital flight” from Russia in a meeting with the Executive Board, but Borgen deflected these concerns over nonresident accounts in the Baltic branches. In a 2013 meeting with the group about these concerns, Borgen emphasized a “need for a middle ground,” In a 2018 press conference Borgen claimed he did not recall to what he was referring in making this statement. (Bruun and Hjejle 50).

Whistleblower Reports Suspicious Activity

In 2014, Howard Wilkinson, a mid-tier executive at the Estonian branch, released a report about suspicious nonresident accounts moving large sums of money through the bank, often from rubles to U.S. dollars. Wilkinson initially sent the message via email to Danske’s internal audit, Baltic banking group, and Compliance group, which included members of the Executive Board (Milne and Winter). The whistleblowing report detailed customers like Lantana Trade LLC., a British company transferring up to $20 million per day through the Estonian branch. Despite these transactions, Lantana had financial records implying dormancy in the UK registry. The LLC held the same address in London as 64 other companies with accounts at the Estonian branch and was owned by individuals from Seychelles and the Marshall Islands, countries known for banking secrecy and money laundering. According to Wilkinson, some nonresident account holders also had connections to individuals entrenched in money laundering schemes such as Igor Putin (Kroft).

In addition to Wilkinson’s evidence of inconsistent information about the identities of the customers of the Estonian branch, the internal audit group at Danske published a critical report of the nonresident business noting suspicious activity. Despite these concerns, CEO Borgen expressed unwillingness to take firm action in a 2014 Board meeting because exiting the offshore business strategy might “significantly impact any sales price” (Milne and Winter). Following that statement, Danske faced regulatory sanctions from the Estonian FSA in 2015, and the Danish FSA enforced similar sanctions after conducting inspections in 2016 that concluded “the bank’s risk-management measures… have been totally insufficient and in violation of the local AML rules” (Bruun and Hjejle 68). In 2015, Deutsche Bank and Bank of America also ended their banking relationships with Danske Bank due to the large amounts of Russian money moving through nonresident accounts at the Estonian branch (Bruun and Hjejle 70). About two years after Wilkinson released the whistleblowing report, Danske completed the closure of its nonresident business at the Estonian branch in 2016 after considerable pressure from AML regulators (Bruun and Hjejle 63).

Several Investigations Launched, Danske Owns Up to Mistakes

In 2017, Danske’s alleged involvement in Russian money laundering schemes became more public as Danish magazine Berlingske published a number of reports investigating if the bank assisted in investing, hiding or converting the proceeds of crimes in an organized manner (Jung, Lund, et al.). The U.S. based consultancy firm Promontory also conducted a root cause analysis on Danske in 2017 and concluded that billions of dollars passed through the Estonian branch in 2013. Promontory cited insufficiencies in AML efforts within the branch, lack of compliance with the recommendations of regulatory bodies assessing risk, and over dependence on local management as reasons why Danske struggled to control nonresident accounts (Investigations into Danske Bank’s Estonian Branch | Danske Bank; Milne and Winter). In the first half of 2018 more reports were published in mainstream media, and consequently Estonia’s general prosecutor, The Danish Public Prosecutor for Serious Economic and International Crime (SØIK), the Danish FSA, the U.S. Department of Justice, and Danish law firm Bruun and Hjejle all launched investigations into the Estonian branch’s involvement in money laundering (Milne and Winter).

On September 19, 2018 Danske released the findings of the investigation from Bruun and Hjejle. According to the findings, $236 billion of nonresident money passed through the Estonian branch from 2007 to 2015 because of inadequate control and money laundering checks at the branch (Bruun and Hjejle 3). CEO Thomas Borgen and Chairman of the Board of Directors Ole Anderson resigned at this time, and Estonian prosecutors detained ten former employees at the Tallinn branch on the basis of knowingly enabling money laundering with Russian customers (Milne). Following these assessments, Danske made the $225 million in profits from the nonresident accounts available “for the benefit of society,” by assuring their donation to an organization that combats financial crime. The bank also invested millions of dollars into improving the IT systems, increasing the number of employees working on AML, increasing employee training on AML and whistleblowing, and closing down banking operations in the Baltic region (Investigations into Danske Bank’s Estonian Branch | Danske Bank).

Involvement of Correspondent Banks

Although the Estonian branch of Danske bank is the central focus of investigation for these regulatory bodies, correspondent banks of Danske are also embroiled in the scandal. Deutsche Bank especially is implicated in the money laundering scandal because of its Moscow based branch’s mirror trading (Jung, Bendtsen, et al., Chan).

Mirror trading, in this case, involves an individual who owns a Russian based company, which buys a stock from Deutsche Bank or Citibank with rubles. The same individual also owns an offshore company in the UK or Cyprus. This offshore company sells the same stock to Deutsche in U.S. dollars (Jung). With this method, the owner converts rubles to dollars while circumventing Russian capital controls. The owner layers the proceeds from crime and “launders” the rubles by passing them through a reputable bank and switching currency. In this transaction the bank would make commissions on the trades and the customer would often make a loss (Jung, Bendtsen, et al.).

Even if the money is not from criminal sources, the bank is still involved in circumventing Russian currency law and should know the identities of its customers well enough to recognize the suspicious behavior of these often loss making trades. Deutsche is embroiled in Danske’s money laundering scandal, even though each mirror trade often occurred in only one bank at a time. The reason is that many of the suspicious nonresident customers exposed in investigations on Danske’s Estonian branch held accounts with similarly suspicious trades at Deutsche (Jung, Bendtsen, et al.) Correspondent banks like Deutsche often assisted Danske with wire transfers and currency exchanges while acting as an intermediary between different countries. As these transactions, including mirror trades, are often key in money laundering schemes, Danske’s correspondent banks are also implicated in the scandal. These banks ignored suspicious activity from nonresident accounts and facilitated the movement of dirty money out of Russia and the Baltic region into clean U.S. dollars (Milne and Winter).

Ethics Considerations

Deontological Analysis and Duty of Care

Danske Bank failed in its fiduciary responsibility to further investigate the identities and transactions of nonresident accounts, improve the AML procedures at the Estonian Branch, and comply with the recommendations made by regulators like the Estonian FSA and Danish FSA, while billions of dollars were laundered through the Estonian branch from 2007 to 2015 (Carlson). Thus, the bank violated the following deontological principles: do not break promises, do not lie, and do not cheat in its conduct with its customers. In addition, Danske failed in its duty of care at the time of the money laundering (Investigations into Danske Bank’s Estonian Branch | Danske Bank).

Duty of care requires fiduciaries “inform themselves ‘prior to making a business decision, of all material reasonably available to them’” (Carlson). Given the number of warnings from financial regulatory bodies and infringements found in AML practices by internal auditors, executives at Danske Bank were likely not acting with care when processing transactions for nonresident accounts. The Bruun and Hjejle investigation indicates the Executive Board did not see issues with the nonresident business earlier because the Estonian branch was so cut off from Copenhagen to the point that any news from the Estonian FSA or internal auditors was severely watered down once it reached the Board. Members of the Board did comment on the Estonian branch’s nonresident affairs prior to 2018, as noted in a 2013 meeting with the Business Banking Group. The Board must have been aware of banks like JPMorgan ending their relationships with Danske over suspicious nonresident accounts. Despite mounting evidence suggesting malpractice in Tallinn, Danske executives turned a blind eye and failed in their duty of care. They likely did so, despite running the risk of being found out and wrecking their bank’s reputation, for reasons left out of the report.

The Bruun and Hjejle press release goes into great detail about the finances of the Estonian branch from 2007 to 2015, but its scope ends there as information about the financial status of the bank as a whole over that time is absent. Like most banks, Danske suffered huge losses after the GFC and struggled to generate profits. Its share price dropped from $43.20 in February 2007 to $6.40 in February 2009. Just as it began to recover, Danske was hit hard by the Eurozone Crisis and the ensuing Irish property crash in 2011, nearly halving its share price to $12.48 from $24 in 2010 (Coppola).

Through all this turmoil, the bank had one glaringly successful profit line: the Estonian branch. With steadily increasing income and a growing customer base, the branch managed an excellent, if not suspiciously alarming, 47% return on equity in 2011. The gains from the nonresident business were not enjoyed solely by shady bookkeepers at the Estonian branch; they bolstered Danske’s profits as a whole as the bank absorbed enormous losses from financial crises (Coppola). If news of corrupt bankers or suspicious behavior found its way to the Board, which it did according to meeting minutes and press conference notes, the executives had profit motives to look the other way (Bruun and Hjejle 45).

Even if communication was poor between the Estonian branch and the headquarters in Copenhagen, there is a conflict of interest as the former head of Baltic operations, Thomas Borgen, later became Danske’s CEO. He made many decisions regarding the nonresident business during his stint managing the Estonian branch. Borgen was unsurprisingly offered the CEO position after his Baltic branches had great success instead of suffering through the GFC like the rest of the bank. He expanded the nonresident business and delayed its closure, even though the Estonian FSA, Danish FSA, and internal auditors expressed concerns about the transactions of and identities behind those accounts (Bruun and Hjejle 84). Had the Bruun and Hjejle press release included information about Danske’s overall finances during the money laundering scandal, the bank would have had a harder time absolving its executives of the blame on the basis of poor communication.

Danske’s executive’s actions violated the trust customers placed in the bank to act ethically. Instead the bank pursued profits unethically so as to speed its recovery from the GFC. (Tan Bhala, 14). The duty of care requires fiduciaries to place their customer’s interests before their own, and to treat people with dignity, as ends in themselves (Carlson). Aside from perhaps putting the interests of the nonresident money laundering customers before those of the bank, Danske put its interest of generating profits, even if in potentially illegal ways, before customers’ interests. By facilitating illegal behavior and failing to protect their customers from the immoral choices of the Estonian branch, Danske compromised its integrity as a trusted financial institution.

Utilitarian Analysis of Danske Bank’s Response

In classical utilitarian thought, ethical decisions are ones that bring the most pleasure or happiness to the greatest number of people (Tan Bhala, 10). In the case of the Danske Bank money laundering scandal, happiness can be understood in the following ways: (1) money earned by bankers at the Estonian branch, (2) money earned by the Executive Board or nonresident customers, (3) the sense of security ordinary customers feel in banking with Danske, (4) the illegal activity reduced when proper AML regulations are followed, and (5) the untainted reputations of Estonian and Nordic finance, including the reputations of Danske and its corresponding banking partners.

Utilitarian analysis consists of choosing the most ethical decision by weighing different outcomes against each other on the basis of the amount of good each one entails. Conversely, deontological analysis arrives at the most ethical decision based on the idea that certain actions, like lying for example, are intrinsically right or wrong. Although the process for arriving at the most ethical decision is different with each theory, both approaches most often arrive at the same verdict of ethical or unethical conduct for a given set of circumstances (Tan Bhala, 9).

In the discussion of fiduciary responsibility and duty of care, a deontological approach concludes that executives at Danske were unethical, according to the principle of the duty of care. In the following section, an utilitarian approach determines if the changes Danske proposed to reduce money laundering going forward adequately compensates for its previous misconduct.

Danske’s Response

Danske has launched several initiatives to make amends for the money laundering scandal and avoid future instances of financial crime within the bank. Danske has ceased banking operations in Estonia, the Baltic region, and Russia following an order on February 19, 2019 from the Estonian FSA. Before electing to focus only on Nordic customers and international customers with “a strong Nordic footprint,” the bank strengthened control over management in the Baltic branches and migrated all branches to the same IT platform for increased transparency (Investigations into Danske Bank’s Estonian Branch | Danske Bank).

To develop a culture of compliance, Danske founded an AML center with 1,200 employees working to fight financial crime and educated approximately 20,000 of its 20,683 employees with an AML e-learning training course. The bank has also provided more information to employees about whistleblowing procedures and scheduled yearly mandatory training to remind them of how the bank protects its employees when reporting on improper conduct. Danske has implemented risk management and compliance in the performance agreements of members of the executive board and senior managers as well as invested over $300 million into improving control routines and IT systems that will better detect suspicious activity in automated transactions. Danske has introduced a compliance position to the Executive Board to encourage earlier detection and executive awareness of suspicious activity (Investigations into Danske Bank’s Estonian Branch | Danske Bank).

Finally, and perhaps most costly, Danske decided to donate the gross income from the nonresident accounts in Estonia from 2007 to 2015 estimated at $225 million “to an independent foundation, which will be set up to support initiatives aimed at combating international financial crime, including money laundering.” This contribution is assured on the condition that the profits are not confiscated by authorities currently investigating the accounts (Investigations into Danske Bank’s Estonian Branch | Danske Bank).

The Good (and its Caveats)

In terms of the money laundering scheme itself, the criminals who passed $236 billion through the Estonian branch derived happiness from the exchange, as did the bankers who earned a commission off the transactions. Members of the Executive Board enjoyed some good while the scheme was undiscovered as their bank was able to rebound after financial crises more quickly, though much of that is outweighed by losing their jobs like Borgen and Anderson did. Even if they kept their work, Board members saw Danske suffer in the wake of the scandal as its stock price plunged nearly 50 percent in 2018 (Wienberg). The same can be said for the ten Tallinn branch employees who were detained by the Estonian authorities, and the other employees who were out of work once the branch shut down. (Milne) Any of the good stemming from the profits earned by the scheme for the bank was also lost after Danske pledged to donate the gross income of the nonresident accounts to an organization set up to combat financial crime (Findings of the Investigations Relating to Danske Bank’s Branch in Estonia).

That being said, the donated money will likely do good when it is contributed to that organization. The amount of good it will do may not compare to the amount of bad the money laundering did, despite the profits being contributed in full. Danske’s involvement in the scheme was unethical as money laundering is not only a crime itself, but also enables harmful illegal behavior like drug trafficking and terrorism funding. Danske’s complicity in activities like money laundering reflects a growing influence of criminals and level of corruption in what the bank claims to be an institution functioning within legal standards.

The Outright Bad

Danske’s involvement in the scandal tainted its own reputation as well as the reputations of it correspondent banks, Estonian finance and Nordic finance. Kilvar Kessler, the chairman of the management board of the Estonian FSA describes the scandal as dealing “a serious blow to the transparency, credibility and reputation of the Estonian financial market.” (Sorensen) The head of the central bank of Denmark’s financial stability division Karsten Biltoft, also expressed concerns about how distrust triggered by Danske would “threaten financial stability” in Denmark. (Wienberg and Levring) Other banks in Estonia and Denmark may have done nothing wrong, yet their brands are damaged by association.

The money laundering scheme also damaged the reputations of Danske’s correspondent banks like Swedbank, Citibank and Deutsche Bank. The customers, employees and shareholders’ trust in Danske was also hurt. The damage to reputations and trust alone affects entire nations, financial institutions and customer bases, which in magnitude is significant enough to outweigh the happiness gained by the few select money launderers who benefitted from the scheme.

Based on utilitarian analysis, the present outcome of Danske’s money laundering scandal was far from the best one possible. Nearly everyone working with or for Danske was harmed by the scheme, the only ones benefitting being the individuals who successfully passed dirty money through the bank. The bank’s decision to be complicit in the money laundering was overall a poor and unethical decision because it failed to generate the most good for the greatest number.

Conclusion

It remains to be seen how much Danske will suffer financially in the coming months and years because of the scandal, although its new chairman Karsten Dybvad says the bank faces “years” of damage control as this downturn will be worse for the bank than the GFC (Wienberg). Applying deontological and utilitarian analysis to the case, results in a conclusion that executives at Danske made unethical choices. Danske betrayed its vision of “being recognized as the most trusted financial partner” and its goal of helping individuals and businesses manage their money (Our Essence). Thus, Danske betrayed the purpose of finance: to help people save, manage and raise money (Tan Bhala).

Works Cited:

Bruun and Hjejle. Report on the Non-Resident Portfolio at Danske Bank’s Estonian branch. 2018, https://danskebank.com/-/media/danske-bank-com/file-cloud/2018/9/report-on-the-non-resident-portfolio-at-danske-banks-estonian-branch-.-la=en.pdf.

Carlson, David. “Fiduciary Duty.” LII / Legal Information Institute, 15 July 2009, https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/fiduciary_duty.

Chan, Michelle. “Case Study: Deutsche Bank Money Laundering Scheme.” Seven PillarsInstitute, 27 April, 2017, https://sevenpillarsinstitute.org/case-study-deutsche-bank-money-laundering-scheme/.

Coppola, Frances. “The Tiny Bank At The Heart Of Europe’s Largest Money LaunderingScandal.” Forbes, 26 Sept. 2018, https://www.forbes.com/sites/francescoppola/2018/09/26/the-tiny-bank-at-the-heart-of-europes-largest-money-laundering-scandal/.

Danish Financial Supervisory Authority. “Danske Bank’s management and governance inrelation to the AML case at the Estonian branch.” Danske Bank, 3 May 2018, https://danskebank.com/-/media/danske-bank-com/pdf/investor-relations/fsa-statements/fsa-decision-re-danske-bank-3-may-2018-.-la=en.pdf.

Financial Crisis 2008, Perpetrators, and Justice, 23 May 2013, https://sevenpillarsinstitute.org/financial-crises-perpetrators-and-justice/.

Findings of the Investigations Relating to Danske Bank’s Branch in Estonia. https://danskebank.com/news-and-insights/news-archive/press-releases/2018/pr19092018. Accessed 5 June 2019.

Garside, Juliette. “Is Money-Laundering Scandal at Danske Bank the Largest in History?” TheGuardian, 21 Sept. 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2018/sep/21/is-money-laundering-scandal-at-danske-bank-the-largest-in-history.

Gronholt-Pederson, Jacob, and Francesco Guarascio. “EU States Force Clearing of Estonian,Danish Regulators over Danske Bank.” Reuters, 17 Apr. 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-danske-bank-moneylaundering/eu-states-force-clearing-of-estonian-danish-regulators-over-danske-bank-idUSKCN1RT0VZ.

Investigations into Danske Bank’s Estonian Branch | Danske Bank. https://danskebank.com/about-us/corporate-governance/investigations-on-money-laundering. Accessed 5 June 2019.

Jung, Eva, et al. “ENGLISH: Links to dead Russian lawyer behind French money laundering probe against Danske Bank.” Berlingske, 13 Oct. 2017, https://www.berlingske.dk/content/item/46902.

Jung, Eva, et al. “English version: Shady clients engaged in suspicious trades at Danske Bank.” Berlingske, 17 Nov. 2017, https://www.berlingske.dk/content/item/12891.

Jung, Eva, Michael Lund, and Simone Bendtsen. Report: Russia Laundered Millions via DanskeBank Estonia. https://www.occrp.org/en/projects/28-ccwatch/cc-watch-indepth/7698-report-russia-laundered-billions-via-danske-bank-estonia. Accessed 5 June 2019.

Kroft, Steve. “How the Danske Bank Money-Laundering Scheme Involving $230 Billion Unraveled.” CBS News, 19 May 2019, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/how-the-danske-bank-money-laundering-scheme-involving-230-billion-unraveled-60-minutes-2019-05-19/.

Lowe, Heather. “Money Laundering and HSBC – How It Affects You.” Global Financial Integrity, 10 Jan. 2013, https://gfintegrity.org/press-release/money-laundering-and-hsbc-how-it-affects-you/.

Milne, Richard. “Prosecutors Charge Ex-Danske Bank Chief in Money-Laundering Probe.” Financial Times, 7 May 2019, https://www.ft.com/content/a78b04ba-70d5-11e9-bf5c-6eeb837566c5.

Milne, Richard, and Daniel Winter. “Danske: Anatomy of a Money Laundering Scandal.” Financial Times, 19 Dec. 2018, https://www.ft.com/content/519ad6ae-bcd8-11e8-94b2-17176fbf93f5.

“Money Laundering.” Investopedia, 3 May 2019, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/m/moneylaundering.asp.

Money Laundering – Financial Action Task Force (FATF). https://www.fatf-gafi.org/faq/moneylaundering/. Accessed 5 June 2019.

Our Essence. https://danskebank.com/about-us/our-essence. Accessed 19 June 2019.

Schwartzkopff, Frances, and Niklas Magnusson. “Danske Bank’s Money Laundering Scandal Damages Client Confidence.” Bloomberg, 14 Jan. 2019, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-01-14/danske-growth-machine-at-risk-as-clients-balk-at-laundering-case.

Sorensen, Martin Selsoe. “Estonia Orders Danske Bank Out After Money-Laundering Scandal.” The New York Times, 20 Feb. 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/20/business/danske-bank-estonia-money-laundering.html.

Tan Bhala, Kara. “The Philosophical Foundations of Financial Ethics.” Research Handbook onLaw and Ethics in Banking and Finance, edited by Costanza A. Russo, Rosa M. Lastra, and William Blair, Edward Elgar, 2019, pp. 2-24.

Tan Bhala, Kara. “The Purpose of Finance.” Seven Pillars Institute, https://sevenpillarsinstitute.org/mission/the-purpose-of-finance/.

Wienberg, Christian. “Danske Bank Has Half Its Value Wiped Away, But Will 2019 Be Better?” Bloomberg, 27 Dec. 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-12-27/danske-has-half-its-value-wiped-away-but-will-2019-be-better.

Wienberg, Christian, and Peter Levring. “Danske Scandal Has Danish Central Bank Citing Systemic Risks.” Bloomberg, 30 Nov. 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-11-30/danish-central-bank-warns-lenders-against-taking-higher-risks.