Tax Avoidance, Its Effects, and Dutch Facilitation

Major tax avoidance helps the few but harms the many.

By Piotr Schulkes

Introduction

Tax avoidance is a persistent feature of our modern economic system. Oliver Bullough, a journalist who has written extensively on tax evasion in Eastern Europe, compared offshore finance to Feynman’s quote: “if you think you understand quantum mechanics, you don’t understand quantum mechanics.” Taxation is dauntingly complex, made more so by misunderstandings in popular culture. When most people think “tax haven”, they imagine the Cayman Islands and Switzerland, while the more informed think Delaware and Cyprus. Rarely does the United Kingdom, where the City of London is at the centre of a vast tax planning network, come to mind. Nor do people consider the Netherlands, with its quaint canals and pot-smoking tourists, to be the single biggest facilitator of tax avoidance in the world.

The Netherlands has become an invaluable agent in the legal arrangements which allow multinational corporations (MNCs) to reduce tax liability to almost 0%. Unsurprisingly, the impact of these structures is detrimental to economic growth and financial equality. Their existence is deeply hypocritical: the Netherlands, a member of the so-called frugal four, proselytizes financial prudence and is loathe to increase the EU’s budget even a few percentage points. At the same time, the Netherlands deprives those countries of billions in corporate tax (Tax Justice Network “Hypocrisy of “Frugal” Netherlands “). This report explains what role the Netherlands plays in a complex legal and organizational network spanning the globe, the sole purpose of which is to reduce corporate taxes. With the recent release of the FinCEN files by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), the importance of challenging these structures is impossible to deny. This network benefits the rich at the expense of the poor, and is maintained by legions of high-powered lawyers and politicians. The end of the report provides two surprisingly simple ways of solving the problem of tax avoidance. One involves more detailed reporting requirements by companies, and the other a new approach to taxing them.

Definitions of Tax Haven, Tax Avoidance, and Tax Evasion

A tax haven in layman terms, is a jurisdiction, be it a country, territory, or state, in which money is placed so that a person or company can reduce and/or hide taxable income. A group of Dutch researchers say a country becomes a tax haven if “it deliberately offers companies who would not otherwise seek to be resident within its territory the means to reduce their taxation charges on royalties, interest, dividends,” and other profits (Dijk). Oliver Bullough writes at length about what he calls Moneyland, where “English libel, American privacy, Panamanian shell companies, Jersey trusts, Lichtenstein foundations, all add together to create a virtual space that is far greater than the sum of their parts” (Bullough). Tax havens go beyond storing money, as they also involve passports for sale and laws beneficial to the rich and powerful and detrimental to those less fortunate. The most technical definition of a tax haven is an offshore financial centre (OFC). Thus, “an OFC is a country or jurisdiction that provides financial services to non-residents on a scale incommensurate with the size and financing of its domestic economy” (Zorome).

This definition is the most competent one, as it also includes so-called ‘conduit OFCs’; countries which facilitate tax evasion and avoidance but where the money does not finally come to rest (those are the so-called ‘sink OFCs’). The Netherlands is a case of the former, and the Cayman Islands and Luxembourg are examples of the latter, but the Netherlands would not be included under the more common definition of tax haven(Garcia-Bernardo et al.).

Tax avoidance and tax evasion are often used interchangeably, but are different entirely when it comes to legal ramifications. Tax avoidance is the legal reduction of taxes through rebates, deductibles, and so forth, while tax evasion is the illegal act of not paying taxes by say, filing false tax returns or understating income. Bullough provides a rough division: tax avoidance is ‘naughty money’, where rich individuals or corporations hide their income and wealth from tax authorities; tax evasion is ‘evil money’, where kleptocrats and thieves hide money they have stolen from people or states. For most people, the difference between the two is mostly semantics. In both cases, societies become poorer, inequality increases, and accountability minimized. These shared outcomes, the fact tax avoidance goes against the spirit of laws, and the reality one needs a legion of lawyers and accountants to benefit from tax avoidance (leading to the unequal application of these laws), argues robustly against companies benefitting from friendly discourse describing their activities. For this reason, the tax avoidance and tax evasion are used interchangeably in this report.

Enablers: How the Netherlands Became a Centre of Tax Avoidance

There are three main reasons why multinationals develop byzantine ownership structures. The first is legal protection. Investments into jurisdictions with underdeveloped or corrupt judiciaries are risky, and companies therefore create subsidiaries in countries where they benefit from and understand the law. The second reason is the other side of the same coin: benefitting from laws of one jurisdiction means one is not beholden to laws of another. Sink OFCs (like the Cayman Islands) have strict privacy laws, to the benefit of account holders in that jurisdiction. Another example is “English libel” from the earlier Bullough quote. This refers to how easily high net-worth individuals (HNWIs) can mount libel cases against newspapers to stop them publishing articles, which investigate their unsavoury financial practices. Many of the esoteric financial products that worsened the 2008 financial crisis were manufactured in offshore financial centres (Lysandrou and Nesvetailova). The third reason is the topic of this report: to minimize tax payments. The Netherlands is invaluable in this operation, moving billions of dollars a year out of reach of tax authorities and into sink OFCs, mostly Bermuda and Ireland (Garcia-Bernardo et al.).

This tax-minimizing practice gained momentum in the 1980s. An example is how Canadian companies would invest in the US. Instead of doing so directly, a Canadian subsidiary of a company would route the money through loans to the Netherlands, the location of their claimed head office, from where it would then be sent to another subsidiary in the Netherlands Antilles in the Caribbean. From here, it would finally arrive in the US at its intended destination. This structure is infinitely much simpler than the back-and-forth seen today, but it allowed taxes on dividends to be reduced from 15% to 5%, and taxes on interest to drop from 30% to 0% (Dijk). This structure, known as the ‘Antilles Route’, was shut down eventually, but served as the pre-eminent method of getting money out of Europe without paying full taxes for a number of years.

The exact method has changed, but the idea remains similar, ensuring the Netherlands remains the global leader in facilitation of tax evasion. Its appeal can be roughly divided into foreign and domestic factors. The Netherlands has historically been a trading nation and has an economy based on international commerce and investment. The first shares, of the Dutch East India Company, were sold there, and some of the first multinationals, Philips and the precursor to Royal Dutch Shell, are Dutch. To make sure these companies were not taxed twice, the Dutch government endeavoured to have double tax treaties with countries where Dutch companies did business (Dijk). These treaties are the reasons the aforementioned hypothetical Canadian company could invest into the Netherlands without taxes. By 1983, the Dutch Central Bank allowed companies to create special financial institutions (SFIs), more commonly known as shell companies or holding companies, in the Netherlands. Today, these SFIs hold assets primarily in Germany, the UK, and the US (Dijk). The FinCEN files show Dutch double tax treaties made the country an appealing destination for ‘investments’ from Russia. In 2014 and 2015 alone more than $675 million was moved out of Russia and into offshore companies through two Dutch intermediaries (Leupen). These financial flows are not genuine investments, but rather oligarchs moving money out of Russia. Thus, the Dutch financial system helps hide ‘naughty money’ – which, at a stretch, can be justified as part of the free market – but also plays a role in concealing money stolen from societies by oligarchs, which is indefensible.

For major globalized companies, the Netherlands has two clear advantages. First, withholding tax (the tax removed by the government at the source of income) is zero for royalty, license, and patent payments. The bonds used in the FinCEN case also have no withholding tax. Second, but closely related, are so-called ‘patent boxes’, where profits linked to products that incorporate patents are bundled together. The combination of these two tools allow very low or non-existent tax bills for companies who can show they use intellectual property in their product. This is especially advantageous for tech companies. In 2016 alone, the Netherlands lost €1.2 billion in corporate taxes because of this construction, and has facilitated similar losses of taxable income in a number of other countries (Berkhout).

However, the appeal of Dutch tax law is not solely for the Silicon Valley giants. 366 companies of the Fortune 500 have at least on subsidiary there. This could be explained away by the fact the Netherlands is a rich country with strong ties to international trade, but the numbers tell another story. The Congressional Research Service found American multinationals reported 43% of foreign earnings in just five countries with a combined population of just over 32 million, among them Bermuda and the Netherlands. That seems unlikely, and it becomes even more improbable when these countries only represent 4% of these companies’ foreign work forces and 7% of their foreign investments. It is hard to believe these workers are so productive they represent output ten times larger than what their numbers indicate. Morgan Stanley has also made enthusiastic use of Dutch tax laws. The company has one hundred and thirteen subsidiaries in the Netherlands (Diese). That seems excessive.

Once companies have established a subsidiary in the Netherlands, the advantageous domestic circumstances give them enticing reasons to stay. The Netherlands has excellent public transport infrastructure, is politically stable, and multicultural. Any travelling businessman will immediately feel at ease in the country because it is predictable and open. This ease applies to companies. While other countries are trying to develop tax laws similar to the Netherlands, they do not have decades of case law and tax experience. As a result, there is still some degree of risk when opening a subsidiary or shell company in a new jurisdiction as the limits of the laws often have not been explored yet. The Netherlands, thanks to its long history of facilitating tax avoidance, has tested “basically all aspects of the participation exemption” in courts (Dijk). In the rare cases that a new tax structure has not been tested in court, corporations can consult with tax authorities about a proposed conduit structure before it is put into action. Truly excellent customer service by the Dutch authorities.

In June 2014, in a token attempt to limit the use of SFIs for questionable purposes, the Dutch government imposed certain requirements on these shell companies. The spirit of the law required a minimum amount of activity in the Netherlands by an MNC to ensure it had real presence in the country. Five months later, the National Court of Audit reported that the requirements were so low any MNC could meet them (Tax Justice Network “Narrative Report on the Netherlands”). The Netherlands has not made what is possibly the most important step towards increasing transparency. Companies based in the Netherlands are not required to report revenues or tax payments on a country-by-country basis, nor how finances flow between subsidiaries (Dijk). Both these steps would be invaluable in limiting tax evasion and ensuring countries around the world, especially developing states, get the taxes owed to them. It is no surprise these requirements are not implemented, as the financial sector is important to maintain Dutch influence (its minor impact on the country’s economy will be discussed later). However, the brazenness of the cooperation between the financial sector and the government is disheartening. Oxfam and the Dutch Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations found that “tax partners from Dutch accountancy firms have key advisory positions for political parties and regularly organize high-level meetings with representatives from the Dutch Ministry of Finance” and that there is ”intensive cooperation” between the Ministry and the tax planning sector (Novib).

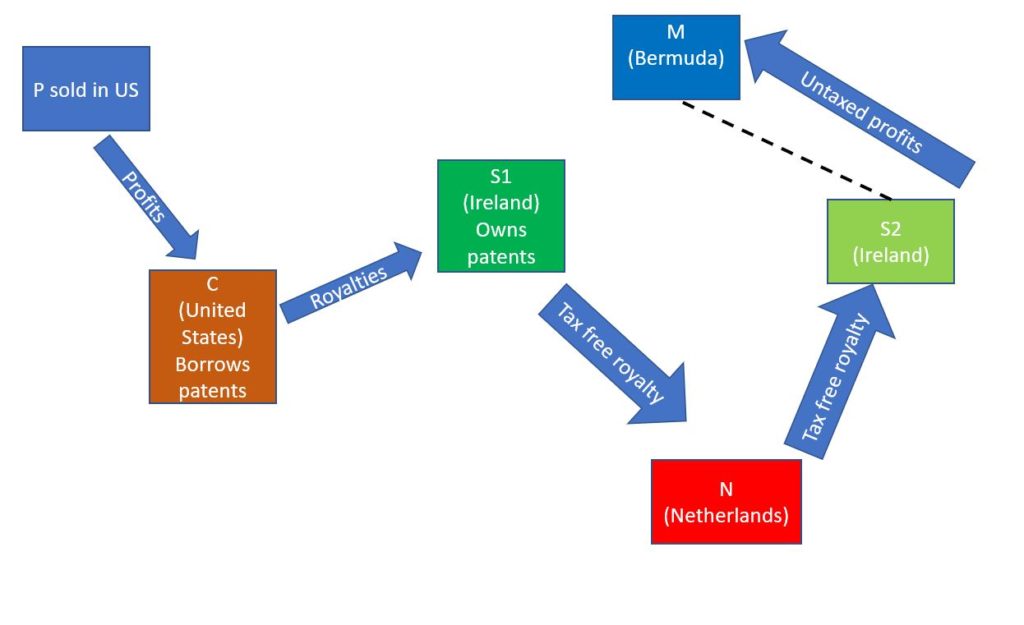

The result of everything discussed so far is a tax structure called the “Double Irish With A Dutch Sandwich.” It works like this:

- Company C is selling a product (P), but does not want its profits to be subject to a high tax.

- To avoid this, company C creates a subsidiary in Ireland whose controlling interest is also in Ireland (S1), to which it gives the patents for P

- When product P is sold in the US, company C now has to pay S1 royalties for its use of the patent (which it is putatively borrowing from S1). This reduces the profits of C to 0, so it does not have to pay taxes

- S2 is formed, with a controlling interest in Bermuda. Because this controlling interest is foreign, S2 does not have to pay taxes in Ireland

- S1 and S2 are considered the same corporate entity in Ireland by US tax authorities as they are part of the same company structure

- For S1 to make royalty payments to S2 without incurring an Irish withholding tax, holding company N is formed in the Netherlands in order to benefit from double tax deals

- S1 pays tax free royalties to N, which in turn pays them to S2, which can then be moved to M in Bermuda if necessary

This tax structure became illegal in 2015 and companies got a five-year window to return the untaxed profits. In 2018, though, Google on its own, moved $25 billion through a Dutch holding company to a Bermuda-based one (Sterling). There are already two replacements, one called the Single Malt, which is the same structure but replaces the Netherlands with Malta, and the second is called CAIA, a 12-step process even more efficient at tax evasion.

The change in laws also does not guarantee genuine change. Bullough describes it as the Moneyland Ratchet, “which inspires highly intelligent people like these analysts to restlessly scan the world for ways the very rich can get very much richer” and “always leads to looser and laxer regulations”(Bullough). The Dutch have resisted EU rules to stop tax competition, which causes states to partake in a race to the bottom to have the lowest tax rate (more on this later) (Ewing). The Dutch foreign investment agency is also saying the quiet part out loud, by promising a “supportive corporate tax structure” on its website.

The Consequences of Tax Evasion: Small Benefits and Huge Drawbacks

The impact of tax avoidance schemes spans the world. The schemes bring well-paying jobs to a small number of people, generally in Western financial centres, but distort economic situations in the tax havens themselves. Tax evasion schemes cause a laundry list of issues in countries where profits are taken offshore instead of taxed, and are a cause of wealth inequality.

Benefits: Localized Earnings

One of the few concrete domestic impacts of helping companies with ‘tax planning’ is the number of highly educated and well-paid professionals required in the industry. In the Netherlands, around 2,500 people are directly employed by the trust sector. This sector creates and manages shell companies. If lawyers, accountants, and tax consultants also involved with this segment of the economy are counted, the number is substantially higher. Despite many trusts having zero employees, the industry around it still generates around €3 billion a year, according to VIMS, the branch organisation for financial services. Researchers have said “it is not clear what this estimate is based on” and instead arrive at €1.7 billion (Dijk). That is not insubstantial in absolute terms, but considering the total amount of money channelled through the Netherlands is around €4 trillion a year, it is a pittance.

The fact the benefits of tax evasion fit into a mere two paragraphs parallels its small positive impact on the world as a whole. In the tax havens themselves – Cayman Islands, British Virgin Islands (BVI), and Bermuda – the industry of tax planning has had a generally positive impact. Jake Bernstein, a journalist who worked on the Panama Papers describes BVI’s pre-tax haven financial situation as relying on “a fledgling tourist trade” which “yielded a bit more than $42 million in 1985,” and drug trafficking, “the only other significant economic activity […] which could not be taxed.” Nine years later, though, the BVI’s incorporation business led to substantial development and “everyone who wanted a job had one,” making the BVI one of the most prosperous small island nations (Bernstein). If one looks away from the loss of culture and the state institutions captured by financial interests, becoming a tax haven has been great for the BVI and island nations like it.

Costs: Globalized Losses

1. Economic Distortions

Tax-friendly policies cause economic distortions in these same nations. In 2017 alone, Bermuda booked $104 billion in profits of American companies, despite having a GDP of only $6 billion. As a result, Bermuda’s economy on a superficial level has a profit to GDP ratio of almost 1900% (Diese). In comparison, the US ratio is about 50%. Equally peculiar is that Bermuda, with a population of about 70,000, was according to US companies, the site of $80 billion in profits, more than France, Germany, China, and Japan together, whose combined population is almost 1.7 billion people (Berkhout). A researcher from the University of London developed a way quantify Zorome’s definition of OFCs, mentioned in the introduction, by looking at how large a role external capital plays in an economy. What he finds is quite surprising. Bermuda is only in the top three in one of his metrics – the ratio between GDP and foreign direct investment (FDI). The Cayman Islands is the runaway winner, leading the list in two metrics and coming second in the third. Foreign bank deposits in the Cayman Islands are 607 times GDP, with a total of more than $1.6 trillion – more than Germany or France. Foreign portfolio investment is 800 times GDP, as roughly 50% of hedge funds are officially based on the islands. The researcher combines the factors to create an offshore intensity ratio: anything between 1 and 1.27 is normal, and countries above 6.35 have a “very high probability to be OFCs”, with the Netherlands being at 6.35, though the number would be “much higher if the officially reported direct investment assets had been used.” The Cayman Islands is in a league of its own, having an offshore intensity ratio of 1400 (Fichtner). The money causing these economic aberrations is siphoned from states around the world, to their detriment and for the benefit of the elite few. The most eyepopping result of tax haven economics is not found in the Caribbean though, but in Ireland. In 2016, the Irish Central Statistics Office claimed the economy had grown by 34% in 2015, a development called “Leprechaun Economics” by Nobel Prize laureate Paul Krugman (Kelpie). This stunning growth was caused by Apple onshoring about $200 billion in 2015 due to changes in tax laws. Unsurprisingly, the move raised a lot of eyebrows and led to an investigation, with the EU imposing a €13 billion fine on Apple, the largest corporate tax fine in history. The case is still on appeal (Brennan).

2. Lower Government Revenues

The impact tax havens have on governments can be broadly divided into domestic issues and transnational issues. The Tax Justice Network (TJN) writes “the secrecy world creates a criminogenic hothouse for […] fraud, tax cheating, escape from financial regulations embezzlement […]and plenty more” and it undermines the “no taxation without representation bargain that has underpinned the growth of modern nation states” (Tax Justice Network “Financial Secrecy Index 2020”). The belief low taxes are good, which will be challenged later, lead to governments giving tax breaks to MNCs to attract their business. The tax breaks are problematic for local communities for a number of reasons. First, lower corporate tax leaves less money for infrastructure and healthcare. This erosion results in the second problem: spending cuts. Less income means less capacity to alleviate inequality and poverty. If governments want to shore up the budget, higher VAT is often used, disproportionately affecting the vulnerable in society. A third drawback of large companies not paying tax is the burden now has to be shouldered by smaller companies who cannot pay for lawyers and accountants to benefit from tax loopholes (Berkhout). This unfair burden reduces their competitiveness, speeding up the demise of small- and medium sized businesses (Hathaway). Tax is not a cost to an economy, but a transfer within it (Tax Justice Network “Tax Wars”), but with companies portraying their tax avoidance as a necessity, and thereby demanding tax holidays or tax cuts, they prioritize their short-term economic gain over the local economy’s long-term sustainability.

If the consequences on the local economy are negative, the impact on developing companies is near cataclysmic. Tom Burgis, in his must-read book The Looting Machine, writes “Where once treaties signed at gunpoint dispossessed Africa’s inhabitants of their land, gold and diamonds, today phalanxes of lawyers representing oil and mineral companies with annual revenues in the hundreds of billions of dollars impose miserly terms on African governments and employ tax dodges to bleed profits from destitute nations” (Burgis).

The Netherlands has been an essential cog in the machine which siphoned at least $255 billion in taxes out of countries and into tax havens (Dijk). Since the 1970s, African countries have lost more than $1 trillion in capital flight, with combined external debts being less than $200 billion. This means “Africa is a major net creditor to the world” but assents are “protected by offshore secrecy” (Tax Justice Network “Financial Secrecy Index 2020”). Developing countries are hit especially hard by tax avoidance, as collecting corporation tax has better value for money than extracting small sums from big populations who primarily work in the informal sector (Shaxson). Even the IMF, a pillar of the neoliberal international order, believes the impact of tax avoidance is “especially troubling” and “jeopardizes a convenient and much-needed tax handle” (Keen). By 2014, developing countries were losing about $100 billion annually form tax evasion. Action Aid, an NGO, estimates another $130 billion is lost due to tax incentives to businesses (Action Aid). That is enough to pay for the schooling of every single child of the 124 million not in school, and fund health interventions for six million children. Based on the findings in the FinCEN leaks, it is estimated that $700 billion has been moved out of Russia into corporate tax havens in the last 25 years. This loss of income is a key reason why most Russians have only seen pitiful improvements in their living standards (Leupen). Yet, suffering African children and Russians are not the target audience of the Dutch foreign investment agency’s “supportive tax structure.”

3. Inequality

Tax avoidance is a driver of inequality. First, it allows the rich and well-connected to siphon more money of out the economy without having to pay their dues. Second, tax avoidance puts increased pressure on those who cannot afford the legal wizardry to be exempted from taxes. The right-wing fevered dream of lower taxes leading to productivity growth has been debunked time and again. The Congressional Research Office concluded in 2012 “there is not conclusive evidence, however, to substantiate a clear relationship between the 65-year steady reduction in the top tax rates and economy growth.” On the other hand, “top tax rate reductions appear to be associated with the increasing concentration of income at the top of the income distribution” (Hungerford). While the Congressional Research Office’s research is not about tax havens, the conclusion is the same: less tax on the wealthy is detrimental to society. In Africa, tax benefits primarily benefit shareholders and owners of corporations, who are already wealthy and predominantly white (Berkhout). The poorer a country is the higher the likelihood of corporations shifting profits out of the country because of tax benefits offered by other countries. A 2014 IMF report showed that developing countries are up to three times harder hit by other countries’ tax rules than rich countries. Tax havens therefore, play a central role in perpetuating global inequality (Johannesen et al.). OECD reports also show that corporate income tax as a percentage of GDP has remained stable, while income taxes have increased. In 2015, the tax-to-GDP ratio has reached the highest level since the OECD started measuring, with income tax and consumption taxes “representing an increasing share of total tax revenues” (OECD). This is despite the fact that the 2010s were a period of sustained stock market growth and corporate profitability.

Repairing Faulty Tax Foundations

Tax competition, claimed to be positive, is a misnomer. The Tax Justice Network believes tax competition “bears no economic relation to competition between firms in a market. They are utterly different economic beasts.” The organisation instead uses “tax wars” because it is more like “trade wars or currency wars than it is like competition – and which more accurately conveys the harm” (Tax Justice Network “Tax Wars”).

The Myth of Tax Competition and Tiebout’s Absurd Hypothesis

As much as companies like to pretend tax is an important factor when deciding where to do business, most recently shown by Amazon’s HQ2 debacle, the numbers prove otherwise. The World Economic Forum does not even mention (low) tax as an explicit boon for competitiveness, though it can arguably be put into the financial market development category. Stability, good infrastructure, and good social services are more important indicators of competitiveness, all of which are paid for by taxes (Sala-i-Martin). A 2013 World Bank Survey found that 93% of investors would have invested even if no tax incentives had been on offer (Berkhout). TJN puts it bluntly, saying “nobody would site a semiconductor factory in Equatorial Guinea just because it offers a more generous tax break than South Korea does” (Tax Justice Network “Tax Wars”). A 2015 survey by the IMF found that “tax incentives very often have no impact on investment decisions of multinationals” and it ranks second lowest on factors helping investors decide where to spend their money (International Monetary Fund).

The belief that tax competition is beneficial is the brainchild of Charles Tiebout, a proponent of the wildly out of touch theory of “foot voting” which involves simply leaving a situation if one is not happy with it. He applies this concept to economics, and argues that people who are dissatisfied with their community leave and live somewhere else. This way, communities compete to get the best balance between goods and taxes, and become highly effective in spending and collecting taxes (Tiebout). This theory works in the hyperrational world of economics, but not in the real world. People stay where they are because of friends, family, marriage, cultural attachments, and a thousand different reasons. The hypothesis also demonstrates a level of obliviousness to assume people have the means to move around constantly to find the best place to live. Yet this detached from reality article has become the foundation of the anti-tax crusade led by free market fundamentalists. When tax wars do attract capital it is often hot money, not long-term investment beneficial to the development of a region or country. Research done by the New York Times shows more than $80 billion a year in tax incentives are given to companies in the US alone. Often, the tax benefits do not pay for themselves, and have severe consequences for the long-term health of communities. New York spends enough annually on tax credits for the movie industry to hire 5,000 public-school teachers. The same tactics are employed around the world: corporations have created a “high-stakes bazaar where they pit local officials against one another to get the most lucrative packages” (Story).

One of the greatest victories of the finance industry is creating and perpetuating the belief deregulation and low taxes are good for society. It allows politicians around the world, especially those in tax havens, to hide behind a veneer of legitimacy when they facilitate unsustainable business practices of multinationals under the guise of “competition” or “business friendliness.”

We know how to solve the issues discussed, but there is, unsurprisingly, an absence of political will and solutions proffered so far have been superficial at best. As mentioned earlier, the Netherlands made the Double Irish with a Dutch Sandwich structure illegal in 2015 in part because they did not want to be considered a tax haven. Companies were given a five-year window to repatriate their profits, though most channelled the funds to another tax haven. Tax lawyers have already found other ways to evade tax, and while the Netherlands has made some steps, they are largely cosmetic. The “new” withholding tax, starting January 1st 2021, is applicable to royalty payments made by a Dutch company to a related company. On the surface, this step stops the Netherlands from being a conduit country for four trillion dollars a year. In practice, this law only applies if the company is in a low-tax jurisdiction. Ireland and Luxembourg, the two countries which are historically the largest recipients of money through the Dutch conduit are not on the government’s list of low-tax jurisdictions. The finance minister, with an impressive degree of self-delusion, says the Dutch list, with more countries on it than the EU blacklist, shows that “we are serious in our battle against tax avoidance” (Rijksoverheid). The so-called substance requirements lack just that, as a company only needs €100,000 in annual salary costs and office space. That is a single well-paid individual, who could in theory be employed by a large number of companies, a common structure in offshore finance. The most cynical ploy, though, is that if a company should be suspected of wrongdoing, the Dutch tax authorities have “the opportunity to challenge the structure [emphasis added].” The Dutch tax office works under high pressure with many employees burning out. Understaffing is normal, and help lines are rife with problems. Thus, the new laws are mere window dressing (Vliet). The FinCEN leaks underline the lack of interest of financial institutions to do the required amount of due diligence. Banks “appear to have no idea whatsoever about whose money they are moving” and “often fail to perform the most basic checks” (Loop).

Two Solutions

1. Country-by-Country Reporting

The two real solutions are related and surprisingly straightforward, compared to the complexity of the problem. First is a focus on transparency. Companies can argue, albeit in bad faith, that disproportionate amounts of profits are being made in small, low-population countries because there currently is no pressure on them to publish country-by-country reporting (CBCR). This allows them to create the aforementioned complex structures to shift profits around in order to get the most beneficial tax structures. CBCR would require MNCs to publish reports such as revenue, profits, taxes and number of employees in each jurisdiction in which they operate (Financial Transparency Coalition). As a consequence, global financial flows would be easier to monitor, taxes are easier to collect – especially for developing countries – and transparency would quickly shine a light on tax evasion. This solution has a low cost for companies, barring their increased tax bill, because MNCs already collect this information for internal purposes. CBCR ensures that the capability deficit in developing countries is not quite as large as it is now. Journalists, scholars, and civil servants who will comb through these databases will find information which is also beneficial to developing nations. With understaffed and outgunned tax authorities, investigative aid from well-funded groups is essential to give direction to prosecutors. Research also shows the more transparent countries are, and with easier access to beneficial ownership (the final owner of a company), the less corruption there is. In addition, cross-border investigations are substantially more straightforward (Martini).

A goal of CBCR is to reduce the effect of transfer pricing. This is the practice of subsidiaries within a company acting as if they are trading a product in a competitive setting, but in reality shifting profits around the corporation to ensure the best tax deal.

2. Unitary Taxation

Related to CBCR is the second solution, called unitary taxation. Today, most companies are treated as a collection of separate entities because of subsidiaries all across the world. Unitary taxation treats these subsidiaries as a single business entity (Picciotto). This method is becoming more common, and has been implemented in some US states and the EU. The UK’s Labour Party committed in 2019 to introducing it in the UK, making it the first major political party in the OECD willing to do so.

Unitary taxation, explained exceptionally well by the TJN, requires companies to be taxed according to the proportion of their economic activity in a country. The Independent Commission for the Reform of International Corporate Taxation (ICRICT), of which Joseph Stiglitz, Nobel Prize laureate, is a member, has a radical three-step view of unitary taxation. The group wants a global minimum corporate tax rate of 25% and thinks it is necessary to ban so-called “carve outs”, like the Dutch “patent boxes” described earlier. The only exception to these two steps is that special economic zones can exist, as long as the average tax rate of a country remains at 25%. That’s the whole plan. However, while the solutions might be straightforward, implementation is fairly unrealistic, as Caribbean tax havens and various other countries have economic interests which go against a globally equitable tax regime. Thankfully, there is precedence for unilaterally implementing unitary taxation. A court case between a trust fund recipient and the United Kingdom, presided over by the European Court of Human Rights, came to the conclusion that double tax treaties (the bread and butter of the Dutch international tax network) should only serve to avoid double taxation and not become an instrument of tax avoidance. Tax Watch UK has proposed this precedent be used to tax royalties from technology companies (Turner).

The biggest problem facing tax justice activists is the complexity of the problem. The idea that tax is bad and unfettered capitalism and deregulation is the path to growth has been in place since the 1980s. Few question this proposition. Raising taxes is politically toxic, especially when it is purposefully misrepresented by those beholden to business interests, and the act is portrayed as government overreach. The nuances of the modern tax system are too complicated to fit into a slogan equivalent to “drain the swamp” or “Brexit means Brexit”. Activists fight an uphill battle against influential moneyed interests and the distrust many have of higher taxes. The solutions are straightforward but the problem requires thousands of words and still then only scratches the surface. Fortunately, a deep understanding of the problem is not required to know that the current economic system is unsustainable. Here, the emergence of Black Lives Matter is a source of hope. Prison reform activists, civil rights groups, and organisations fighting police violence have existed for decades, but only appeared in the mainstream after Ferguson in 2014. After George Floyd’s murder, anti-racist activism has dominated news coverage in the US and spilled over into Europe. It has led to more conscientious consumption, focusing on black-owned businesses and companies who have genuine humanitarian bona fides. Tax justice is still on the fringes of civic activism, but the increasingly untenable wealth disparities and the shameless tax evasion of multinationals may propel tax fairness to the centre of political discourse. The complexity of tax evasion is its greatest shield. Tax injustice permeates everything, be it perpetuating racist institutional structures, worsening global inequality, or undermining sustainable growth and our capabilities to combat climate change. Taxation is inseparable from these issues, and by associating tax justice with the major questions facing the world today, the idea gains ideological legitimacy and popular appeal.

References

Action Aid. “A Level Playing Field? The Need for Non-G20 Participation in the Beps Process ” Action Aid, 2013. https://www.actionaid.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/beps_level_playing_field_.pdf.

Berkhout, Esme. “Tax Battles: The Dangerous Global Race to the Bottom on Corporate Tax

” Oxfam, 2016. general editor, Oxfam UK, https://d1tn3vj7xz9fdh.cloudfront.net/s3fs-public/bp-race-to-bottom-corporate-tax-121216-en.pdf.

Bernstein, Jake. Secrecy World : Inside the Panama Papers Investigation of Illicit Money Networks and the Global Elite. First edition. edition, Henry Holt and Company, 2017.

Brennan, Joe. “Ireland Wins Appeal in €13 Billion Apple Tax Case.” The Irish Times https://www.irishtimes.com/business/economy/ireland-wins-appeal-in-13-billion-apple-tax-case-1.4305044. Accessed 29-07-2020.

Bullough, Oliver. Moneyland : Why Thieves & Crooks Now Rule the World & How to Take It Back. Profile Books, 2018.

Burgis, Tom. “The Looting Machine : Warlords, Oligarchs, Corporations, Smugglers, and the Theft of Africa’s Wealth.” First edition. edition, xi, 321 pages, 16 unnumbered pages of plates, Public Affairs,, 2015. Contributor biographical information http://www.loc.gov/catdir/enhancements/fy1511/2015930296-b.html

Publisher description http://www.loc.gov/catdir/enhancements/fy1511/2015930296-d.html.

Diese, Steve. “Offshore Shell Games.” Open Society Foundation, 2017. general editor, the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy PIRG Education Fund, https://itep.org/wp-content/uploads/offshoreshellgames2017.pdf.

Dijk, Weyzig, Murphy. “The Netherlands: A Tax Haven?” National Committee for International Cooperation and Sustainable Development, 2010. general editor, Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1660372.

Ewing, Jack. “The Netherlands, a Tax Avoidance Center, Tries to Mend Its Ways.” New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/20/business/netherlands-tax-avoidance.html. Accessed 28-07-2020.

Fichtner, Jan. “The Offshore-Intensity Ratioidentifying the Strongest Magnets for Foreign Capital.” translated by Depratment of International Politics, City Political Economy Reserach Centre, 2015. general editor, City Univeristy London, https://www.city.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/287138/CITYPERC-WPS-201502.pdf.

Financial Transparency Coalition. “Country by Country Reporting.” https://financialtransparency.org/issues/country-by-country-reporting/.

Garcia-Bernardo, Javier et al. “Uncovering Offshore Financial Centers: Conduits and Sinks in the Global Corporate Ownership Network.” Scientific reports, vol. 7, no. 1, 2017, pp. 6246-6246, PubMed, doi:10.1038/s41598-017-06322-9.

Hathaway, Litan. “Declining Business Dynamism in the United States: A Look at States and Metros.” Brookings Institute https://www.brookings.edu/research/declining-business-dynamism-in-the-united-states-a-look-at-states-and-metros/?utm_source=link_newsv9&utm_campaign=item_175499&utm_medium=copy. Accessed 29-07-2020.

Hungerford, Thomas. “Taxes and the Economy: An Economic Analysis of the Top Tax Rates since 1945 ” US Congress, 2012. general editor, Congressional Research Service, http://graphics8.nytimes.com/news/business/0915taxesandeconomy.pdf.

International Monetary Fund. “Options for Low Income Countries’effective and Efficient Use of Tax Incentives for Investmen.” International monetary Fund, OECD, World Bank, UN, 2015. general editor, International Monetary Fund, https://www.imf.org/external/np/g20/pdf/101515.pdf.

Johannesen, Niels et al. “Are Less Developed Countries More Exposed to Multinational Tax Avoidance? Method and Evidence from Micro-Data.” The World Bank Economic Review, 2019, doi:10.1093/wber/lhz002.

Keen, Simone. “Is Tax Competition Harming Developing Countries More Than Developed?” Tax Notes International, International Monetary Fund, 2004. http://www.taxjustice.net/cms/upload/pdf/Keen_TNI_copyright_tax_competition_developing.pdf.

Kelpie, Colm. “‘Leprechaun Economics’ – Ireland’s 26pc Growth Spurt Laughed Off as ‘Farcical’.” Independent.Ie https://www.independent.ie/business/irish/leprechaun-economics-irelands-26pc-growth-spurt-laughed-off-as-farcical-34879232.html. Accessed 29-07-2020.

Lysandrou, Photis and Anastasia Nesvetailova. “The Role of Shadow Banking Entities in the Financial Crisis: A Disaggregated View.” Review of International Political Economy, vol. 22, no. 2, 2015, pp. 257-279, doi:10.1080/09692290.2014.896269.

Martini, Maira. “Who Is Behind the Wheel? Fixing the Global Standards on Company Ownership.” Transparency international, 2019. general editor, Transparency International, https://images.transparencycdn.org/images/2019_Who_is_behind_the_wheel_EN.pdf.

Novib, Oxfam. “Interne Overheidsdocumenten Leggen Belastinglobby Bloot.” Oxfam Novib https://www.oxfamnovib.nl/persberichten/interne-overheidsdocumenten-leggen-belastinglobby-bloot. Accessed 28-07-2020.

OECD. “Revenue Statistics: Special Feature: Current Issues on Reporting Tax Revenues.” 2016. general editor, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development., https://www.oecd.org/tax/tax-revenues-reach-new-high-as-the-tax-mix-shifts-further-towards-labour-and-consumption-taxes.htm.

Picciotto, Sol. “Towards Unitary Taxation of Transnational Corporations.” Tax Justice Network, 2012. https://www.taxjustice.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Towards-Unitary-Taxation-Picciotto-2012.pdf.

Rijksoverheid. “Nederland Stelt Zelf Lijst Laagbelastende Landen Vast in Strijd Tegen Belastingontwijking.” https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/actueel/nieuws/2018/12/28/nederland-stelt-zelf-lijst-laagbelastende-landen-vast-in-strijd-tegen-belastingontwijking.

Sala-i-Martin, Klaus Schwab; Xavier. “The Global Competitiveness Report 2017-2017.” the Global Competitiveness Repor, World Economic Forum, 2017. general editor, World Economic Forum, http://www3.weforum.org/docs/GCR2016-2017/05FullReport/TheGlobalCompetitivenessReport2016-2017_FINAL.pdf.

Shaxson, O’Hagan. “A Competitive Tax System Is a Better System.” New Economics Foundation, 2013. https://www.taxjustice.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Mythbusters-2013-competitive-tax-system-is-bad-tax-system-.pdf.

Sterling, Toby. “Google to End ‘Double Irish, Dutch Sandwich’ Tax Scheme.” https://www.reuters.com/article/us-google-taxes-netherlands/google-to-end-double-irish-dutch-tax-scheme-filing-idUSKBN1YZ10Z.

Story, Louise. “As Companies Seek Tax Deals, Governments Pay High Price.” New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/02/us/how-local-taxpayers-bankroll-corporations.html?pagewanted=all. Accessed 14-08-2020.

Tax Justice Network. “Financial Secrecy Index 2020.” Financial Secrecy Index, Tax Justice Network, 2012. https://fsi.taxjustice.net/en/.

—. “Hypocrisy of “Frugal” Netherlands Lambasted by Tax Haven Watchdog.” Tax Justice Network https://www.taxjustice.net/2020/07/20/hypocrisy-of-frugal-netherlands-lambasted-by-tax-haven-watchdog/. Accessed 25-07-2020.

—. “Narrative Report on the Netherlands.” Financial Secrecy Index, Tax Justice Network, 2019. general editor, Tax Justice Network, https://fsi.taxjustice.net/PDF/Netherlands.pdf.

—. “Tax Wars.” Tax Justice Network https://www.taxjustice.net/topics/race-to-the-bottom/tax-wars/.

Tiebout, Charles. “A Pure Theory on Local Expenditures.” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 65, no. 5, 1956, pp. 416-424, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/257839.

Turner, George. “A Question of Royalties.” Tax Watch UK https://www.taxwatchuk.org/taxing_uk_tech_royalties/. Accessed 15-08-2020.

Vliet. “Pressure of Work at Tax Office Is Costing the Treasury Billions, Says Union.” https://www.dutchnews.nl/news/2014/03/pressure_of_work_at_tax_office/. Accessed 12-08-2020.

Zorome. Concept of Offshore Financial Centers in Search of an Operational Definition. International Monetary Fund,, 2007. IMF eLibrary http://elibrary.imf.org/view/IMF001/01330-9781451866513/01330-9781451866513/01330-9781451866513.xml.