Mylan’s EpiPen Pricing Scandal

By: Andreas Kanaris Miyashiro

Each year about 3.6 million Americans are prescribed EpiPen, the epinephrine auto-injector. The EpiPen is a life-saving treatment for anaphylactic reactions, which are caused by allergens such as nuts, seafood, and insect bites. A sharp increase in EpiPen’s price between 2009 and 2016 caused outrage, and prompted debate over whether Mylan N.V, the owner of EpiPen, acted unethically. Beyond the behaviour of Mylan, EpiPen’s price increases raise questions about the conditions of the US pharmaceutical market, and whether existing regulations and laws are sufficient to protect consumers.

Epipen Price Increases

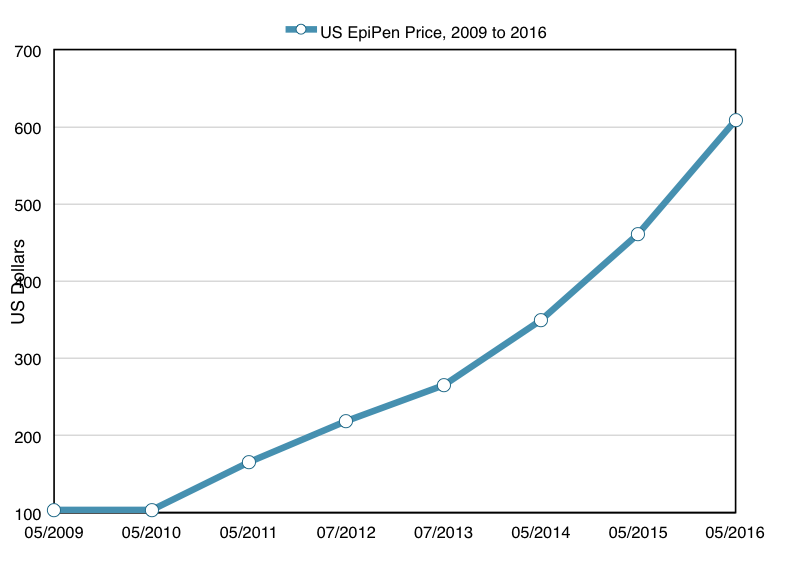

In 2007, Mylan N.V. acquired the right to market EpiPen as part of its acquisition of Merck KgaA. In 2009, Mylan began to steadily increase the price of EpiPen. In 2009, the wholesale price (the price which pharmacies paid) was $103.50 for a two-pack of autoinjectors. By July 2013 the price was up to $264.50, and it rose a further 75 percent to $461 by May of 2015. By May of 2016, the price rose again up to $608.61. Over a seven year period, the price of EpiPen had risen about 500% in total.

Mylan’s Colossal Marketing Efforts

In tandem with these price increases, Mylan embarked on a strategy to cement the market dominance of EpiPen, while expanding the market for epinephrine as a whole. The first element of this strategy consisted of extensive marketing campaigns designed to raise awareness about the dangers of anaphylactic reactions. Mylan’s marketing efforts including television advertising, as well as some other less traditional advertising approaches. In 2014, for example, Mylan struck a deal with Walt Disney Parks and Resorts which produced a website and several storybooks designed for families living with severe allergies distributed in 2015.

In addition, Mylan embarked on an extensive lobbying campaign. Mylan successfully lobbied the FDA in order to broaden the wording of the label of the drug, such that it could be prescribed to those who were ‘at risk’ of experiencing an anaphylactic reaction, in addition to those who had experienced anaphylaxis in the past. The company also added lobbyists in 36 states between 2010 and 2014, in order to pressure lawmakers to require epinephrine be made available in public schools. The rate at which Mylan hired new lobbyists during this period was faster than any other US company, according to the Center for Public Integrity. Increasingly, states have passed laws designed to encourage epinephrine injections to be made available in schools. In 2006, Nebraska became the first state to introduce a requirement that public schools must be able to provide epinephrine injections. Mylan’s lobbying efforts helped to accelerate this trend. A further nine states have introduced similar requirements since 2006, some prompted by much publicised deaths as a result of anaphylaxis. Virginia’s 2012 law, for example, followed 7-year-old Amarria Johnson’s death at a Chesterfield County school from a reaction to peanuts. A further 38 states passed laws permitting epinephrine in schools during the same period. In 2013, President Obama signed off on a federal law, which provides financial incentives for states to require epinephrine treatments in schools.

The rate at which Mylan hired new lobbyists during this period was faster than any other US company, according to the Center for Public Integrity.

Mylan’s lobbying efforts helped to increase the availability of epinephrine in schools. Simultaneously, Mylan attempted to increase the number of EpiPens sold to schools by establishing the ‘Epipen4Schools’ program in 2012. Schools that sign up to the program receive four free EpiPens. The scheme not only helps to increase the visibility of the EpiPen brand, but also has the potential to be lucrative for the company in the short term. Donations of EpiPens are tax deductible. Mylan is likely able to deduct the cost of producing each EpiPen which it donates plus 50% of the difference between the production cost and the sticker price. In addition, schools which signed up for the EpiPen4Schools program were offered discounted prices to buy more EpiPens, provided they signed an agreement to the effect that the schools would ‘not in the next 12 months purchase any products that are competitive to EpiPen(R) Auto-Injectors.’ This provision was discontinued in July, 2016, according to a statement Mylan gave to Congress. In the long term, Mylan’s Epipen4Schools program was clearly designed to cement a strong consumer base for the EpiPen. Nicholson Price, an assistant professor at the University of Michigan Law School, describes the company’s business model as giving customers ‘the first hit’ for free.

Mylan’s strategy to increase sales and market share of EpiPen proved highly effective between 2007 and 2016. The product gained market share, from about 90% in 2007 when Mylan first purchased the rights to produce EpiPen to around 95% in 2015 and early 2016. Annual prescriptions for EpiPen products more than doubled to 3.6 million during the same period, according to IMS Health data. In 2007, the total US market for epinephrine was around $207 million a year. In 2015, and 2016, Mylan alone exceeded a billion dollars in EpiPen sales.

Controversy and Lawsuits in Response to Price Increases

In the summer of 2016, however, Mylan’s fortunes began to turn. The last round of price increases, which saw the wholesale price of a two pack of auto injectors rise to about $608 drew widespread criticism from the public and lawmakers. Multiple congressional committees requested Mylan explain the rapid price increases, resulting in a hearing by the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform in September of 2016. Heather Bresch, CEO of Mylan since January of 2011, faced harsh criticism during her testimony. Bresch was unable to answer questions about revenues and the company’s patient assistance programs, but defended Mylan’s business practices and refused to accept the assertion the company had raised the prices of EpiPen’s to increase profits. Bresch insisted the price surge was a result of increased research and development costs, as well as the costs of Mylan’s EpiPen4Schools program. In addition, she claimed that half of the wholesale price of EpiPens are received by middlemen such as insurance companies and pharmacy benefit managers, and that the US healthcare system was partially to blame for rising costs.

In response to criticism about the price increases, Mylan announced it would reduce the price of EpiPen through increased financial assistance in the form of savings cards that would cover up to $300 of the cost for those who have private health insurance. In addition, Mylan raised the income threshold for families who are uninsured or underinsured to be eligible for free EpiPens from under $48,600 a year to under $97,200 a year. Despite the fact that the new savings cards allowed patients to eliminate up to $300 of co-pay in buying an EpiPen, critics have pointed out the scheme is not a substitute for lowering prices. Though the amount the patients pay in co-pay for EpiPen is significantly reduced in using the savings card, insurance companies continue to pay for the high remaining cost of the drug. This results in higher healthcare premiums. For this very reason, such savings cards cannot be used by patients covered by Medicaid. Discounts such as this are considered ‘kickbacks’ which incentivise patients to buy pharmaceutical products, while leaving the government to pay for the remaining costs. As such, Harvard Medical School professor Aaron Kesselheim criticised the savings cards as a ‘classic public relations move’ which fails to address the fundamental problem of high prices.

Lawsuit 1: Mylan Misclassified EpiPen as a generic drug

In September, 2016, increased scrutiny of Mylan’s business practices led to questions being raised about the drug classification of EpiPen. Mylan misclassified EpiPen as a generic drug, in order to avoid the higher rebates drug companies must pay when they sell their brand-name products to state Medicaid programs. Pharmaceutical companies selling generic drugs pay rebates of 13 percent of the average manufacturer’s price, while companies which sell brand-name drugs must offer discounts of 23 percent off either the average price, or the difference between the average price and the best price they have negotiated with any other American payer, depending on which option provides the bigger discount. Brand-name manufacturers must also pay further rebates if their products’ prices rise faster than inflation.

Mylan misclassified EpiPen as a generic drug, in order to avoid the higher rebates drug companies must pay

Patented drugs such as EpiPen are typically considered to be brand-name drugs, but Mylan classified the EpiPen as a generic on the basis that the active substance (epinephrine) used in EpiPens is common and widely used. This clearly was a misclassification, considering the extremely high market share which EpiPen enjoys, and the fact that Mylan owns a patent for EpiPen which will expire in 2025. The Department of Justice pursued legal action against Mylan in September of 2016. The case was resolved in a $465 million settlement in October. As part of the settlement, Mylan agreed to reclassify EpiPen as a branded drug.

Lawsuit 2: Antitrust violation

Also in September of 2016, New York attorney general Eric T. Schneiderman launched an antitrust investigation into Mylan, on the basis that the sales contracts with schools as part of the EpiPen4Schools program violated antitrust laws. The investigation is ongoing, but it seems likely that Mylan may eventually face consequences for the illegal contracts, which forced schools to refrain from buying EpiPen’s competitors in order to buy EpiPens at discounted prices.

In December of 2016, Mylan again attempted to address criticisms of EpiPen’s price by releasing a generic version of EpiPen with a list price of $300 for a two-pack, less than half the price of the brand-name version. A press release from Mylan stated this ‘unprecedented action, along with the enhancements we made to our patient access programs, will help patients and provide substantial savings to payors.’ It is highly unusual for a pharmaceutical company to release a generic competitor for its own brand name product. As well as serving as an attempt to quiet criticism of EpiPen’s price, the move may have been motivated by Teva pharmaceutical’s development of its own generic epinephrine auto-injector, expected to win FDA approval at some point in 2017. Mylan’s release of its own generic device might have been an attempt to steal market share from Teva’s product

Lawsuit 3: Class action based on RICO

In April of 2017, Mylan faced two new lawsuits related to their business practices in selling EpiPen. The first, filed April 3rd, was a class-action lawsuit filed by three EpiPen purchasers who claim that Mylan engaged in illegal schemes to dominate the market with Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs). PBMs serve as intermediaries between insurance companies, pharmaceutical companies, and pharmacies. The plaintiffs claim that agreements reached between Mylan and a number of PBMs including CVS Caremark, Express Scripts Holding Co and OptumRX, were illegal under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act. Mylan allegedly offered the PBMs large rebates in exchange for favouring EpiPen over competitors.

Lawsuit 4: Anti-competitive acts

The second lawsuit, filed April 24th by pharmaceutical company Sanofi SA, also accused Mylan of illegally attempting to prevent competition for the EpiPen. Sanofi claims that Mylan offered rebates to PBMs, insurers, and state Medicaid agencies on the condition they would not reimburse patients to buy Sanofi’s Auvi-Q rival auto-injector device. Sanofi seeks damages against Mylan for the hundreds of millions of dollars they may have lost in sales due to these illegal agreements. Any damages which Mylan pays to Sanofi will be tripled under US antitrust law.

Determinants of EpiPen Pricing

A number of different factors interact in determining the price for a specific drug in a particular country. These include the market for the drug in question, the judgment and business practices of the manufacturer, and the conditions of the wider pharmaceutical market and healthcare system in the country of interest. Examining these factors in relation to the EpiPen can explain the dramatic increase in its price between 2009 and 2016.

Background on the Epinephrine Market

Epinephrine is a hormone used to treat anaphylaxis (severe allergic reactions) since 1977. Anaphylactic reactions can be deadly due to swelling and closing of the airways. Epinephrine injections, by triggering the ‘fight or flight’ response, quickly causes patients’ airways to open, preventing death from suffocation.

Marginal Costs

Epinephrine is widely used and very cheap to produce. It takes less than one US dollar to manufacture one millilitre of epinephrine. A single EpiPen dispenses less than a third of that amount. What makes the EpiPen valuable is it quickly administers the correct dose of epinephrine, and is simple enough to operate that a person suffering from anaphylaxis can self-administer the treatment if necessary. Still, the manufacturing cost of EpiPen is estimated to be under $10 per two pack.

R&D Cost

The marginal costs of most drugs to manufacturers are typically low. More influential supply-side factors in determining drug pricing are research and development costs and marketing costs. Heather Bresch, in her September 2016 congressional hearing, testified that the price increases for Epipen were in part due to research and development costs involved in improving the drug. Since purchasing EpiPen in 2007, Mylan has made incremental upgrades to the EpiPen, designed to make the drug easier to administer and clarify instructions about how to use the product. Daniel Kozarich, an expert on pricing, suggests that the EpiPen price increases up to 2013, by which time the price of a two-pack had risen to $264.50, could justifiably be explained as compensation for research and development costs. This cannot be said for the subsequent price increases between 2013 and 2016.

Marketing Cost

Mylan engaged in extensive marketing of the EpiPen, paying about $35 million for advertising in 2014, for example. Usually, such heavy marketing costs are reserved for new products, which are often advertised widely in order to introduce to the drugs to the medical community. The amount Mylan spends in advertising, however, is dwarfed by its yearly sales of EpiPen, which exceeded $1 billion for the first time in 2015. Mylan’s aggressive advertising efforts have proved very successful in expanding the size of the market for EpiPen, and cannot justify an over 500% increase in price during a seven year period.

‘Willingness to Pay’ and Pricing

While supply-side factors may have played a part in Mylan’s determination to increase prices, demand-side factors may have been more influential. For the most part, drug prices in the US predominantly rest on demand-side considerations. As William Comanor and Stuart Schweitzer, professors at the UCLA School of Public Health explain, the key factor in determining pharmaceutical prices is patients’ ‘willingness to pay’ for a given product.

The most important factor determining the magnitude of patients’ ‘willingness to pay’ for a product is the therapeutic advance it provides. New drugs with a significant therapeutic advantage over old ones are the subject of large amounts of demand, which warrant high prices. The EpiPen, however, has been on the market since 1987. Typically, innovative products such as the EpiPen offering a large therapeutic advance are introduced with high prices that decrease over time. This pricing strategy is referred to as ‘skimming’. EpiPen’s price increases under Mylan are unusual given that the product has been on the market for three decades.

A Lack of Competition

The high price of EpiPen can better be explained by the lack of competition the product faces. The amount of competition a particular drug faces in its specific category has a significant effect on price, as prescribing physicians must select between rival drugs. A 1998 study by Lu and Comanor finds that launch prices of pharmaceutical products are significantly lower when there are more branded rivals in direct competition with them.

During the period in which Mylan increased EpiPen prices, few direct competitors existed to threaten EpiPen’s market dominance in the US. In the UK and other European countries, the EpiPen competes against the Jext auto injector from ALK pharma, and the Emerade auto injector from Valeant, among others. In contrast, prior to June of 2013, when the Adrenaclick autoinjector was reintroduced by Amedra, few direct competitors to the EpiPen existed in the US. Since its relaunch, the Adrenaclick has faced manufacturing constraints, which prevented it from gaining significant market share until recently. Auvi-Q, manufactured by French pharmaceutical Sanofi S.A., was designed to rival the EpiPen, but was on the market for only three years before Sanofi voluntarily recalled all Auvi-Q devices due to concerns the auto injectors were administering incorrect doses. The Auvi-Q is the most significant competitor to EpiPen worldwide, but its recall in the US damaged its reputation. Since the beginning of 2017, EpiPen has lost a significant amount of market share in the US, partly to cheaper products such as the generic version of the Adrenaclick which costs only $110, but also to Mylan’s own generic version of EpiPen. Between 2007, and 2016, EpiPen’s market share in the US hovered between 90 and 95%. Between January and March of 2017, EpiPen’s market share in the US has been only 71%, according to a study by AthenaInsight.

Fiona Scott Morton and Lysle T. Boller of the Yale School of Management comment on the subject of EpiPen’s lack of competition that “there is a tension between imitating a reference product like EpiPen without imitating its injector”. Generic applicants hoping to create a new version of a patented product face navigating through unclear FDA guidelines concerning how to avoid infringing on the existing patent. In the case of EpiPen, developing competitor drugs may have been particularly difficult due to the fact the patented element being the injector rather than epinephrine, which is an old generic. Any injector imitating EpiPen is likely to infringe on EpiPen’s patent protection. A similar patent issued helped to facilitate the recent dramatic price increases of Evzio, an autoinjector for naloxone, used to treat opioid overdose. As with EpiPen, Evzio’s patented element is the delivery device rather than the drug itself.

It should be noted that one factor which helped reduce competition for the EpiPen in the US was Mylan’s own business practices. Multiple lawsuits, such as the 2016 lawsuit regarding the EpiPen4Schools program, revealed Mylan may have violated antitrust laws by offering rebates and discounts to buyers such as insurance companies and schools, in exchange for agreements which would preclude those buyers from purchasing any of EpiPen’s competitors.

The US Healthcare System and EpiPen pricing

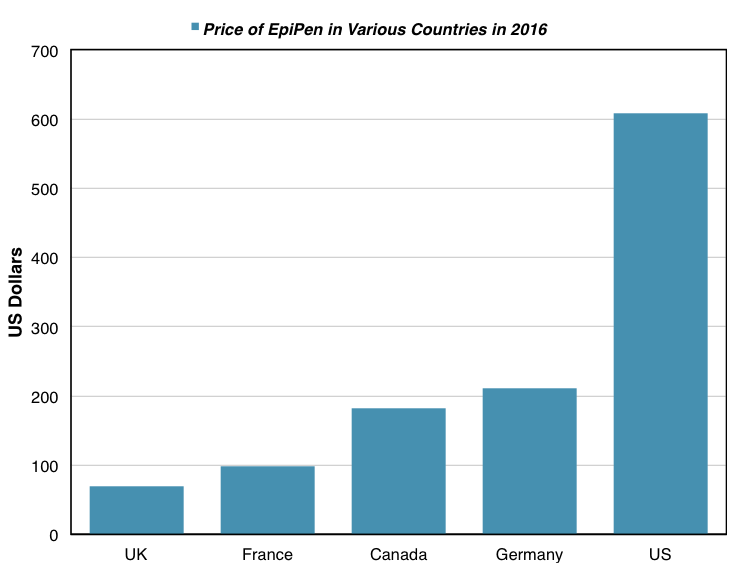

The list price of a two-pack of EpiPen is about $69 in the UK, about $100 in France, and about $200 in Germany. These prices are dramatically lower than the $609 list price of EpiPen in the US. As was mentioned previously, EpiPen prices in Europe are lower in part due to a larger number of direct competitors to the EpiPen there. But the most significant factor causing this price differentiation is the healthcare system in the US. The UK, France, and Germany all have different forms of universal health care systems, which severely restrict the price of pharmaceutical drugs.

UK Pharmaceutical Price Controls

In the UK, there exists a long-held consensus among lawmakers that there is a need for price regulation of pharmaceuticals, as the supply of pharmaceuticals is viewed as non-competitive due to the patent system. Within the Medicines, Pharmacy, and Industrial (MPI) division of the UK Department of Health, the Pricing and Supply branch oversees drug price controls. The Pricing and Supply branch negotiates an agreement, called the Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme (PPRS) with the pharmaceutical industry that sets a cap to profits which pharmaceutical companies can make on NHS business. Pharmaceutical companies are required to repay any amount that exceeds this fixed cap. This agreement is renegotiated every time the existing PPRS agreement expires, which typically occurs 4-5 years after they come into effect. PPRS agreements explicitly aim to create a balance between ‘[supporting ] the NHS by ensuring that the branded medicines bill stays within affordable limits and [delivering] value for money’ and ‘promoting a strong and profitable pharmaceutical industry that is both capable of and willing to invest in sustained research and development’. The UK is a hub of research and development in the pharmaceutical sector, and has continued to attract investment, despite the decline in pharmaceutical research and development in Europe as a whole. PPRS agreements aim to control prices such that pharmaceutical companies’ profits are largely in line with the profits of British industry in general, without damaging this important sector of the UK economy. Of course, the PPRS was implemented on the basis that the NHS is the sole healthcare provider for about 90% of the UK population. A system such as the one the PPRS sets out is not be feasible in the US, where no universal public healthcare option exists.

The effects of the PPRS in relation to the cost of EpiPen are striking. The National Health Service (NHS), the public healthcare provider in the UK, pays £53 per two pack for EpiPen, then distributes them to patients who pay only £8.40.

A Lack of Price Controls in the US

In the US, in contrast, a lack of price controls set by the government allows drugs to be sold at whatever prices pharmaceutical companies see fit. State Medicaid programs mandate that pharmaceutical companies sell these drugs at a rebate, which is higher or lower depending on whether the drugs in question are classed as innovators (brand-name drugs) or generics. However, even taking into account rebates, certain drugs such as EpiPen are sold to state Medicaid programs at far higher prices than they are sold to the NHS in the UK.

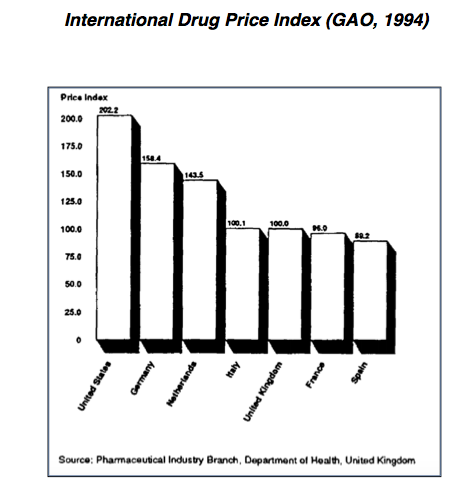

This does not necessarily mean all drug prices are much higher in the US than they are in other countries. Reports by the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) in 1992 and 1994 show that the cash prices for the same branded products are generally higher in the United States than elsewhere. However, the GAO reports, and other studies of a similar nature fail to account for a number of factors which obfuscate price comparisons.

One issue is the GAO report relies on established nominal prices of drugs. These prices do not take into account the rebates and discounts granted to large-scale buyers of pharmaceutical products. This is a huge oversight, considering these bulk buyers comprise the largest segment of demand for pharmaceutical products in the US. Given the prices at which large-scale buyers buy drugs are not disclosed, it is difficult to estimate the magnitude of how this skews the GAO results.

Even more significantly, the GAO report fails to account for the influence of generic drugs in the US pharmaceutical market. Generic drugs are more widely used in the US than in most other countries, accounting for about half of the total sales in pharmaceutical products, and are also generally much cheaper than their branded counterparts. The generic version of the EpiPen introduced by Mylan costs about half the price of the branded version, for example. As such, it is insufficient to simply compare US prices of popular branded drugs to those in other countries. The market share of generic drugs, and their prices should also be compared. William Comanor and Stuart Schweitzer, professors at the UCLA School of Public Health provide the following example to illustrate this point:

‘Suppose that half of US prescriptions for Cimetidine, a popular H2 blocker for gastric reflux and ulcers, are filled by the generic version, the price of which is, say, $104 per hundred, while the price of the branded product, Tagamet, is $167. The average price is $135.50. Suppose further that the prices of both versions of the drug are lower in Canada, with a price of Tagamet of $150 and a generic price of $100. If the generic version’s market share is only 20% in Canada, the average price there is $140, which is higher than the average US price, even though the prices charged for both products are lower in Canada.’

It should be noted this argument is predicated on the idea that generic drugs are identically effective to branded drugs, which is not necessarily the case. Generic drugs must be bioequivalent to their branded counterparts under US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) rules, and the FDA considers generic drugs therapeutically equivalent to brand-name drugs. However, the inactive ingredients in branded drugs may result in slightly different outcomes for patients than generic drugs in some cases. Furthermore, as was the case with the EpiPen until Mylan introduced its own generic version of the product, some pharmaceutical products do not have generic counterparts.

In sum, the problem of inflated pharmaceutical prices does not apply to all drugs in the US. Many drug prices are well regulated in the US by market forces. The main conclusion from empirical studies comparing US drug prices to drug prices in other countries is the US system gives pharmaceutical companies license to sell certain drugs, most often brand-name drugs, at extremely inflated prices.

Many drug prices are well regulated in the US by market forces. The main conclusion from empirical studies comparing US drug prices to drug prices in other countries is the US system gives pharmaceutical companies license to sell certain drugs, most often brand-name drugs, at extremely inflated prices.

PBMs and Pricing Opacity

Heather Bresch, during her December 2016 testimony to the House Oversight committee, claimed the ‘opaque and frustrating’ healthcare system in the US was partly to blame for price increases. Rather than a lack of regulation in the US giving license to companies to increase prices, the healthcare system actually forces companies such as Mylan to raise prices, according to Bresch.

There is some degree of truth to this assertion. Some commentators suggest the US healthcare system suffers from a lack of transparency, which results in inflated pharmaceutical prices.

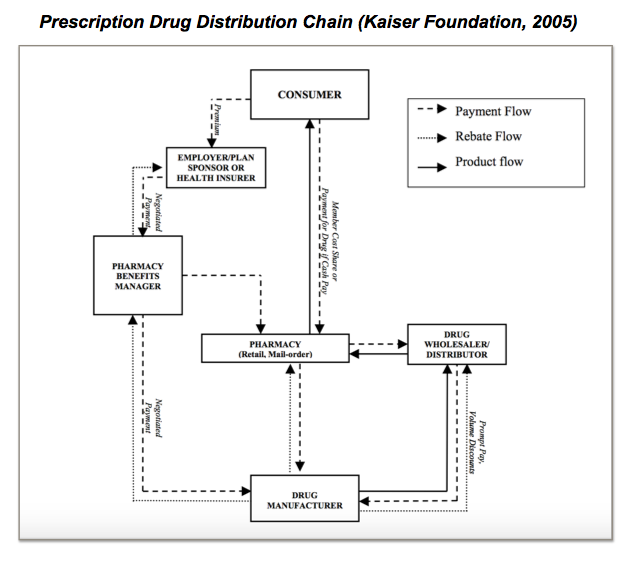

Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs), the ‘middlemen’ who bridge the gap between drug manufacturers, insurance companies, and pharmacies are one of the players who are most at fault for creating opacity in the US health system.

Fundamentally, PBMs serve an important function in the US health system. Their core purpose is to aid insurance companies, HMOs, and large employers who purchase drugs for their beneficiaries. PBMs help these large buyers to process claims, and make transactions between the various players involved in providing drugs to insured patients. The beneficiaries themselves buy drugs from local pharmacies. PBMs reimburse pharmacies for the cost of the drug, based on the price the pharmacy paid for the drug, and the size of the co-payment. The PBMs themselves receive payments both from the large-scale buyers of drugs such as insurance companies, but also from drug manufacturers who pay them rebates taken from the amount that they receive from pharmacies who sell their drugs. The drug manufacturers receive revenue equal to the list price of drugs minus the rebates they provide to PBMs. PBMs negotiate rebates with manufacturers, meaning that various PBMs receive differential rebates when selling the same brands of drugs.

This system, working effectively, has a number of advantages. The rebates system permits manufacturers to charge different prices to different buyers and creates a complex system of differential pricing, responsive to differential demand. Large-scale buyers pay less than the full list price of drugs due to rebates. Patients receive drugs, and pay only the co-pay amount.

In addition, PBMs should have a beneficial effect on the demand side of the pharmaceutical market, as PBMs buy drugs in large quantities on behalf of insurance companies. Ideally, PBMs should augment the elasticity of demand, and improve competition in place of consumers, whose demand is inelastic and who are uninformed about competing products. On the other hand, if PBMs do not respond to price changes in an appropriate way, they risk distorting the market. If a rival company begins selling a drug, which is a close substitute for another drug at a lower price, demand for the rival’s drug should rise accordingly. If PBMs, as large-scale buyers, fail to increase the amount of the rival drug that they purchase, there is a risk the rival company will not be able to generate sales and market share. The incentive to lower prices in the first place is removed, and pharmaceutical companies are likely to continue charging their existing customers high prices rather than attempt to increase sales by lowering prices. As such, PBMs have the capacity to distort the effects of competition.

The fundamental problem with the operation of PBMs currently is that the savings generated by rebates are not passed on directly to consumers. As Fiona Scott Morton and Lysle T. Boller of the Yale School of Management note, ‘rebates are never made public because they reflect the competitive advantage of both the PBM and the brand’s manufacturer’. As such, PBMs are able to profit from the discrepancies between the price at which the manufacturers sell them the drugs, and the prices at which pharmacies and insurance companies buy them. For example, if a manufacturer increases the price of a particular drug, the PBM might be paid a rebate for the extra cost. However, the insurance company purchasing the drugs eventually will not be aware of this additional rebate the PBM is receiving. The rebate simply becomes profit for the PBM.

As such, PBMs have strong incentives to buy and distribute drugs from companies offering them high rebates, rather than those who sell drugs at lower prices. Low prices save patients and insurance companies money, whereas high rebates result in higher profits for PBMs. PBMs’ earnings would be significantly reduced if pharmaceutical companies curtail price hikes, as is illustrated by a 2013 Morgan Stanley report.

As a result, PBMs distort demand rather than improving its elasticity. PBMs facilitate high drug prices, encouraging pharmaceutical companies to raise prices but increase rebates. High prices are translated into higher premiums charged to consumers by insurance companies, but fall hardest on those without insurance, who face paying the full list price of expensive products such as EpiPen.

Bresch’s comments have an element of truth in light of these facts. If EpiPen were to lower prices rather than reduce rebates to PBMs, they would risk losing sales given that PBMs prefer to purchase products with high prices. On the other hand, the buying practices of PBMs do not necessarily encourage price increases as they do not profit from price increases in themselves. Furthermore, Mylan may have entered into illegal, anticompetitive agreements with PBMs as is alleged by the class action lawsuit filed in April 2017. The lawsuit raises the possibility that rather than suffering from the practices of PBMs, Mylan benefitted from them. Ultimately, Mylan is culpable for increasing prices.

Background on Mylan N.V.

Mylan N.V., an American generic and brand-name pharmaceuticals company, was founded in 1961. Initially, Mylan was a small generics-only drug company, but it expanded into the brand-name sector when it introduced a highly successful new formulation of the diuretic Dyazide in 1987.

Through a number of acquisitions, Mylan grew to be one of the largest pharmaceutical companies in the US, and one of the largest generic drug producers in the world. In 2007, Mylan made its most significant acquisition ever, purchasing Merck KGaA’s generic’s arm in a $6.6 billion deal. As part of the same deal, Mylan gained the right to produce and distribute EpiPen. According to a press release by Mylan, the acquisition had the potential to triple the company’s revenue.

A History of Controversial Business Practice

The recent controversy surrounding Mylan’s practices is unsurprising given Mylan’s history of questionable business decisions:

- In December 1998, the FTC charged Mylan with restraint of trade, monopolisation and conspiracy to monopolise the markets as a result of their price increases for two widely-prescribed anti-anxiety drugs, lorazepam and clorazepate.

- In January 1998, Mylan raised the wholesale price of clorazepate from $11.36 to $377.00 per bottle of 500 tablets.

- In March of 1998, the wholesale price of lorazepam was increased from $7.30 for a bottle of 500 tablets to $190.00. According to the FTC, Mylan entered into anticompetitive agreements with ProFarmica, a company producing raw ingredients required to manufacture the two drugs. The agreements restricted the supply of these raw ingredients in order to facilitate Mylan’s dramatic price increases. After 32 states joined the suit against Mylan, a $100 million settlement was reached in 2000.

- In October 2009, the US Justice Department brought a lawsuit was brought against Mylan concerning false claims to State Medicaid programs. The plaintiffs claimed that Mylan had deliberately misclassified drugs (including nifedipine extended release tablets, flecainide acetate, selegiline HCL) sold to State Medicaid companies as generic drugs, when they should have been classified as innovator drugs. Mylan misclassified the drugs for the purpose of avoiding the higher rebates which generic drugs are subject to under state Medicaid programs. In October of 2009, the case was settled for $124 million.

What is striking about these cases of illegal misconduct is that they closely mirror misconduct that Mylan would later carry out in relation to EpiPen. The September 2016 lawsuit against Mylan, resulting in a $465 million settlement, was a result of Mylan illegally avoiding rebates to state Medicaid programs just as it had done in 2009. The three separate lawsuits Mylan has faced since the October 2016 settlement are all related to claims that Mylan violated antitrust laws in contracts selling EpiPen, the same crime Mylan was charged with in 1998. While illegal behaviour such as this is unfortunately common amongst Pharmaceutical companies operating in the US, Mylan’s repeat offences suggest the company has bred a culture of questionable business practices transcending changes in management over time. Studying Mylan’s history of illegal and exploitative conduct, the company’s decision to raise EpiPen prices to an unethical extent is unsurprising.

According to reporting by the New York Times, high level executives at Mylan operate on principles far removed from what Mylan’s mission statement espouses. According to Mylan’s website, management ‘[challenges] every member of every team to challenge the status quo’ and the business model of the company puts ‘people and patients first, trusting that profits will follow’. According to anonymous sources within the company who spoke to the New York Times, a number of mid-level executives began to grow concerned about EpiPen price increases in 2014, feeling the prices were reaching exploitative levels. When these concerns were aired to Robert Coury, Mylan’s chairman, he replied that ‘anyone criticising Mylan, including its employees, ought to go copulate with themselves’.

Ethics Analysis of Mylan N.V. Acts

As the analysis illustrates, there are a number of interrelated factors contributing to the high prices of pharmaceutical products in the US. These factors deserve to be the subjects of scrutiny, and inform attempts to reform the US health market. However, the ultimate responsibility for drastic price increases lies with pharmaceutical companies.

Heather Bresch’s Response to Criticism of Mylan

In her 2016 testimony to Congress, Heather Bresch argued Mylan was responsible for a ‘tremendous amount of good… for millions of patients in the U.S and around the world’. She made a number of claims to prove this assertion.

Firstly, she argued Mylan was responsible, through its advertising and advocacy efforts, for dramatically increasing awareness and use of EpiPens. The cost of these efforts contributed to price increases. According to Bresch ‘the issue of EpiPens has two equally critical dimensions — price and access.’

Secondly, Mylan had invested in research and development aimed at improving the EpiPen. This also contributed to price increases. The combined costs of research and development of EpiPen, plus advertising and lobbying costs amounted to $1 billion.

Thirdly, the opacity and complexity of the drug distribution chain in the US resulted in higher prices.

Finally, Bresch claimed that Mylan only profited about $50 per EpiPen, or $100 per two pack in total. Furthermore, a new generic version of EpiPen was being developed which would be priced at $300, and new savings vouchers had been introduced which offered patients up to $300 off the price of their co-pay for EpiPen.

Refuting Bresch’s Response

Bresch’s response to criticism of EpiPen’s price was disingenuous and misleading, for a number of reasons.

Overriding goal was to increase sales

Mylan’s advertising and advocacy efforts were beneficial in that they successfully increased awareness of the dangers of anaphylaxis. However, they clearly were aimed at increasing EpiPen’s sales rather than preventing harm. The strategies Mylan employed as part of this campaign demonstrate this. Mylan enticed schools in to signing anticompetitive agreements that precluded them from purchasing EpiPen’s competitor products as part of the EpiPen4Schools program. Mylan’s aim was not only to encourage schools to make epinephrin injections available, but also to ensure that schools would buy its product alone.

Mylan’s advertising campaign also crossed ethical boundaries, deliberately misleading customers. In 2012, Mylan released an advertisement that implied that as long as anaphylaxis sufferers had an EpiPen on hand, they could eat whatever allergenic foods they wanted. Heather Bresch and other executives approved the ad, despite concerns being raised about its misleading message in a number of stages of the internal review process. Reportedly, Bresch suggested that it was best to be ‘bold’ in advertising. Mylan pulled the ad subsequent to a record number of consumer complaints being sent to the FDA. The complaints claimed the ad overstated the efficacy of EpiPen.

In 2012, Mylan released an advertisement that implied that as long as anaphylaxis sufferers had an EpiPen on hand, they could eat whatever allergenic foods they wanted.

These details of Mylan’s advertising and advocacy campaign illustrate that the overriding aim of the campaign was clearly to increase sales of EpiPen. The campaign may also have had altruistic motivations, as Bresch suggests, but these were a secondary objective.

In any case, Mylan’s advertising and lobbying were highly successful in expanding the market for epinephrine auto injectors, increasing sales of EpiPen by over 400%. The increases in sales more than compensated for the costs of the campaign

R&D costs insufficient to explain price increase

Furthermore, the research and development costs of improving the EpiPen, as previously mentioned, can only reasonably be used to justify the price increases which occurred up to 2013. While Bresch claimed the combined cost of advertising, lobbying, research and development exceeded $1 billion, the House Oversight Committee commented that none of Bresch’s financial data presented was substantiated. Bresch also claimed during the hearing that Mylan had saved the federal government $180 billion during its ownership of EpiPen. Bresch presented no evidence in support of this claim, and failed to even elaborate the reason why it might have been the case.

Bresch’s claims about the amount of profit from each EpiPen were proved to be incorrect after subsequent analysis. Independent estimates suggest that Mylan profits $80 per EpiPen, and $160 per two-pack, 60% more profit than Bresch claimed in the hearing.

EpiPen price an outlier, even in the context of the US

While Bresch’s claims about the opacity and complexity of the US health system have an element of truth, it is doubtful that the operation of PBMs could have necessitated price increases of the magnitude that Mylan carried out. PBMs were responsible for the price increases only insofar as they may have discouraged competition and enabled Mylan to increase prices without reducing sales. The ultimate responsibility for raising prices lies with Mylan, particularly considering Mylan may have entered into anticompetitive agreements with PBMs.

Insufficient response to price increases by Mylan

Furthermore, the discount vouchers and the generic version of EpiPen Mylan introduced in response to criticism were insufficient to solve the pricing problem. As previously mentioned, the savings cards are only available to families with private health insurance, and up to $97,200 a year combined income. Families with under $28,000 in income are typically eligible for Medicaid coverage. This leaves only a margin of $69,200 in income within which families are eligible for the savings card (excluding individuals covered by Medicare). Furthermore, many families and individuals who have income too high to be eligible for Medicaid or Obamacare feel they cannot afford private health insurance. In sum, the subset of patients eligible to use the savings card for EpiPen is small. In cases where patients are able to use the savings cards, insurance companies absorb most of the costs of the savings, leading to higher premiums.

The generic version of the EpiPen is perhaps a more effective measure to lift the financial burden on patients. However, many commentators suggest that Mylan’s introduction of the generic EpiPen was a preemptive strategy to steal market share from Teva pharmaceuticals, which is set to release its own generic epinephrine autoinjector. It is also important to note that $300, the cost of the new generic, still represents a 200% markup of EpiPen’s price in 2009.

Given that Bresch’s explanations for the dramatic increases in EpiPen pricing do not withstand scrutiny, it seems clear that Mylan’s motivation for the price increases was simply to increase profits. Having a near monopoly on the epinephrine auto-injector market, and knowing that demand for EpiPen is relatively inelastic given that the drug is an essential, life-saving treatment, executives at Mylan believed that they could raise prices without reducing sales. Clearly, Mylan’s acts fall into the category of exploitative and unethical behaviour.

Conclusion and Policy Prescriptions

In light of Mylan’s EpiPen price-gouging, it is clear that there is an need for reform of the US health system such that pharmaceutical companies are prevented from raising prices of essential medicines to exploitative levels.

Price Controls

Given the effectiveness of the PPRS in the UK, price-controls (or indirect price controls through laws which limit profits) are the most obvious solution. However, It is a matter of debate whether price controls would be beneficial overall in the context of the US pharmaceutical market.

Detractors of pharmaceutical price controls argue that price controls might discourage valuable innovation in the US pharmaceutical market. The pharmaceutical industry is particularly fast-moving, so it would be a difficult market for regulators to govern effectively. Regulators may struggle to regulate drugs because they might be uninformed about valuable research, be captured by the industry given the power of lobbyists in the US, or lack the resources to keep up with changes in science or the cost of production

‘Reference pricing’, a popular form of government price controls utilised in Germany, Italy, and Spain among other countries, illustrates the difficulties regulators face in controlling pharmaceutical prices. In a reference pricing system, drugs are classified into therapeutic classes based on the way in which they attack diseases. Prices of drugs are capped based on their therapeutic class, Clearly, such a system might discourage innovations which offer therapeutic advances, as the classification system dis-incentives companies from formulating new drugs which are more effective but fall into the same therapeutic classes as existing drugs.

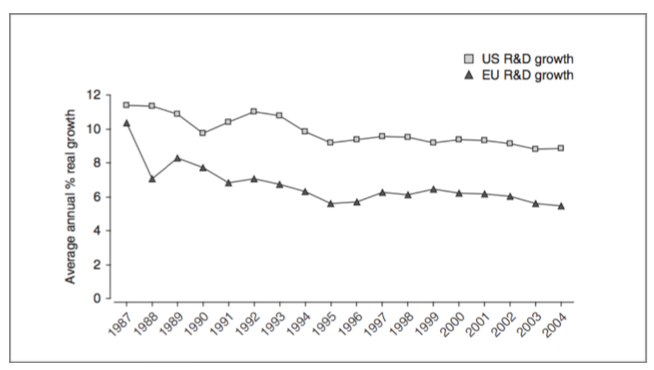

A study by Joseph Golec and John A. Vernon reach similar conclusions, finding that the US would have never formulated 117 new medicines and would have lost 4368 research jobs had European-style price controls been implemented over a 19 year period.

In addition to disincentivising companies from innovating, price controls might restrict drug companys’ financial ability to fund research and development. Ronald Vogel, researcher at the Center for Health Outcomes and PharmacoEconomic Research of the University of Arizona, finds that pharmaceutical price controls in European countries result in reduced research and development spending by drug companies. Vogel concludes that price controls ‘[reduce] the amount of profit available for further R&D, which is a detriment to consumers worldwide’ and in effect invalidates the benefits of patent protection. A study by Joseph Golec and John A. Vernon reach similar conclusions, finding that the US would have never formulated 117 new medicines and would have lost 4368 research jobs had European-style price controls been implemented over a 19 year period.

Average annual real growth in US and EU pharmaceutical R&D spending

between 1987 and 2004 (Golec and Vernon, 2010)

The cost of reducing development of new drugs is heavy. An econometric study by Frank Lichtenberg (2002) shows that between 1960 and 1997, every $1,345 spent on pharmaceutical research and development resulted in an additional U.S. life year (meaning a full healthy year of a person’s life). The introduction of new drugs not only improves patient outcomes, but also significantly expands the number of patients who can be treated who suffer from a given condition.

The central question in the debate over whether price controls should be introduced into the US drug market, then, is whether it is worth correcting the injustice of limited cases of price-gouging at the cost of damaging patient outcomes on a somewhat wider scale. Some politicians, such as Democrats Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders, have voiced their support for price controls. The political will to create price control legislation does not yet exist on a large scale, however.

Targeted Price Negotiation

Considering the deleterious effects that wide ranging price controls could have, some analysts have suggested that limited, targeted price controls might prove more effective in controlling excessive prices while preserving innovation. Richard G. Frank, of Harvard Medical School, and Richard J. Zeckhauser, Harvard Kennedy School of Government, propose a framework for drug price negotiation designed to correct market imperfections related to ‘MISCs’. MISCs are drugs subject to a combination of a monopoly and insurance subsidised consumption and can be identified by the following characteristics:

A) Being a unique product with few competitors

B) Likely to be paid for under the reinsurance benefit provided by Medicare

C) Represents a significant claim on spending by the Part D program of Medicare

In Zeckhauser and Frank’s framework, drugs with the fulfilled criteria could be subject to a mandatory negotiated payment system, not dissimilar to the PPRS negotiation in the UK. The price negotiations would take into account a number of factors, such as the therapeutic advance offered by the drug, in calculating how much it should cost. The pricing regulations would be in effect until competitors entered the market. This particular framework is designed specifically for the market inefficiency resulting from high-cost drugs which are bought largely by State Medicare programs. The fact that Medicare buys MISCs in large quantities distorts the market, as several players in the process of distributing the drugs, including patients and doctors have no incentive to seek lower prices or adjust their buying practices because the price of the drugs are subsidised.

…companies such as Mylan holding virtual monopolies over segments of the market could be required to submit to price negotiation. Zeckhauser and Frank’s framework is designed to ensure that there continue to be strong incentives for companies to create new, innovative products.

It is reasonable to imagine that Zeckhauser and Frank’s framework could be implemented on a larger scale, tailored to correct a wider number of market imperfections. For example, companies such as Mylan holding virtual monopolies over segments of the market could be required to submit to price negotiation. Zeckhauser and Frank’s framework is designed to ensure that there continue to be strong incentives for companies to create new, innovative products. As such, a large-scale version of the framework could prove effective in regulating prices in a manner that does not have a significant impact on the creation of new drugs.

An Alternative to Price-Controls

Even moderate forms of price controls such as those discussed above would likely be strongly opposed by the pharmaceutical industry, which has significant lobbying power in the US. An alternative approach to limiting pharmaceutical prices might encompass two dimensions: (1) encouraging competition, and (2) ensuring that competition is effective in regulating price.

As previously discussed, EpiPen’s high price was in part a result of its lack of competitors in the US. Increased competition in certain sectors within the pharmaceutical market might help to prevent excessive price increases. Encouraging competition in the pharmaceutical market might involve a number of reforms. Instructing the FDA to use more resources in approving drugs, especially those in the biosimilar and generic categories, in order to prevent delays would be particularly beneficial.

As analysis of the practices of PBMs illustrates, competition does not always have the desired effect of decreasing prices in the US drug market. As such, encouraging competition is insufficient to solve the pricing problem. Imperfections in the market, which prevent competition from having the desired effect could be corrected through a number of reforms. The issue of PBMs, for example, might be corrected by legislation mandating that rebate rates be published by PBMs. This would prevent the pricing opacity that encourages PBMs to buy products with higher rebates rather than those with lower prices.

Disadvantages to this alternative approach to limiting drug prices include its complexity, and also the fact that, since it is an indirect, ‘soft’ approach to limiting prices, it may not be effective in every case. Inevitably, there would be cases of price gouging, even if such regulations were implemented.

A Need for Reform

Despite the numerous challenges that face lawmakers in preventing high drug prices, there is no doubt this is an area which urgently requires reform. Just as it is wrong to price gouge during a state of emergency when essential supplies are scarce, it is wrong that companies can exploit vulnerable populations who require drugs by raising prices to extreme levels. Public outrage and even lawsuits are insufficient to solving the pricing problem as EpiPen’s case illustrates. Even in the face of reputational damage and numerous lawsuits, Mylan has not decreased the price of EpiPen.

In the absence of drug price reforms, it is important that lawmakers ensure as many Americans as is possible have health insurance. Those without health insurance are affected most deeply by drug price increases, often having no choice but to buy drugs such as EpiPen at their full list price. Recent Republican proposals for healthcare reform, which cut Medicaid and risk reducing the number of insured Americans by up to 22 million, are dangerous for this reason.

-x-

Bibliography

Bartolone, Pauline. “EpiPen’s Dominance Driven By Competitors’ Stumbles And Tragic Deaths.” NPR, NPR, 7 Sept. 2016, www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/09/07/492964464/epipen-s-dominance-driven-by-competitors-stumbles-and-tragic-deaths.

Comanor, William S., Stuart O. Schweitzer, Vernon, John A., and Manning, Richard L. “Determinants of Drug Prices and Expenditures.” Managerial and Decision Economics 28.4‐5 (2007): 357-70. Web.

Court, Emma. “Mylan’s EpiPen Sales Have Taken a Hit.” MarketWatch, MarketWatch, 10 May 2017, www.marketwatch.com/story/mylans-epipen-sales-have-taken-a-hit-2017-05-10 .

“Follow the Pill: Understanding the U.S. Commercial Pharmaceutical Supply Chain.” The Henry J. Kaiser Foundation, Mar. 2005. Kaiser Foundation.

Goldberg, Robert. “Race Against the Cure: The Health Hazards of Pharmaceutical Price Controls.” Policy Review 68 (1994): 34. Web.

Golec, Joseph, and John Vernon. “Financial Effects of Pharmaceutical Price Regulation on R&D Spending by EU versus US Firms.” PharmacoEconomics 28.8 (2010): 615-28. Web.

Greene, Jan. “EpiPen Controversy Reveals Complexity Behind Drug Price Tags.” Annals of Emergency Medicine 69.1 (2017): A16-19. Web.

Johnson, Carolyn Y., and Catherine Ho. “How Mylan, the Maker of EpiPen, Became a Virtual Monopoly.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 25 Aug. 2016, www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/2016/08/25/7f83728a-6aee-11e6-ba32-5a4bf5aad4fa_story.html?utm_term=.c539c2d9306f .

Johnson, Carolyn Y. “Why Mylan’s ‘Savings Card’ Won’t Make EpiPen Cheaper for All Patients.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 25 Aug. 2016, www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2016/08/25/under-pressure-mylan-will-expand-patient-assistance-for-epipen/?utm_term .

Johnson, Carolyn Y. “EpiPen CEO to Defend Lifesaving Drug’s Soaring Price in Front of Lawmakers.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 21 Sept. 2016, www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2016/09/21/what-to-expect-when-congress-takes-on-epipen-maker-mylan/?utm_term=.9d182e90e904.

Koons, Cynthia, and Robert Langreth. “How Marketing Turned the EpiPen Into a Billion-Dollar Business.” Bloomberg.com, Bloomberg, 23 Sept. 2015, www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-09-23/how-marketing-turned-the-epipen-into-a-billion-dollar-business.

Larson, Erik, and Jared S Hopkins. “Mylan’s EpiPen School Sales Trigger N.Y. Antitrust Probe.” Bloomberg.com, Bloomberg, 6 Sept. 2016, www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-09-06/n-y-s-schneiderman-launches-probe-into-mylan-epipen-sales.

Leonard, Kimberly. “Mylan’s CEO Hit Over Multi-Million Dollar Salary Amid EpiPen Price Controversy.” U.S. News & World Report, U.S. News & World Report, 21 Sept. 2016, www.usnews.com/news/articles/2016-09-21/mylan-head-defends-epipen-price-gouging-in-capitol-hearing.

Lichtenberg, Frank. “Sources of U.S. Longevity Increase, 1960-1997.” NBER Working Paper Series (2002): 8755. Web.

Lopez, Linette. “These Companies You’ve Never Heard of Are about to Incite Another Massive Drug Price Outrage.” Business Insider, Business Insider, 12 Sept. 2016, www.businessinsider.com/scrutiny-express-scripts-pbms-drug-price-fury-2016-9.

Lopez, Linette, and Lydia Ramsey. “Congress Railed on the Maker of EpiPen.” Business Insider, Business Insider, 21 Sept. 2016, www.businessinsider.com/mylan-ceo-heather-bresch-house-oversight-committee-hearing-epipen-2016-9.

Morton, Fiona Scott, and Lysle Boller. “Enabling Competition in Pharmaceutical Markets.” Brookings, Brookings, 2 May 2017, www.brookings.edu/research/enabling-competition-in-pharmaceutical-markets/.

Sedgley, Michael David. An Analysis of the Government-industry Relationship in the British Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme. (2004). Print.

Relakis, Maniadakis, Kourlaba, Shen, and Holtorf. “Systematic Review on the Impacts of Strict Pharmaceutical Price Controls-PHP199.” Value in Health 16.7 (2013): A486. Web.

Santerre, Rexford, and John Vernon. “Assessing Consumer Gains from a Drug Price Control Policy in the U.S.” NBER Working Paper Series (2005): 11139. Web.

Rosenthal, Elisabeth. “The Lesson of EpiPens: Why Drug Prices Spike, Again and Again.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 2 Sept. 2016, www.nytimes.com/2016/09/04/opinion/sunday/the-lesson-of-epipens-why-drug-prices-spike-again-and-again.html.

Tunney, Kelly. “How Many People Use EpiPens In America? Mylan’s Price Increase Is Taking Advantage Of Its Users.” Bustle, Bustle, 26 Aug. 2016, www.bustle.com/articles/180800-how-many-people-use-epipens-in-america-mylans-price-increase-is-taking-advantage-of-its-users.

Tuttle, Brad. “EpiPen Prices: Mylan CEO Heather Bresch & Big Pharma Scandal | Money.” Time, Time, 21 Sept. 2016, www.time.com/money/4502891/epipen-pricing-scandal-big-pharma-politics/.

United States, Congress, Jagar, Sarah F. “Prescription Drugs: Prices and Regulation in Canada and Europe.” Prescription Drugs: Prices and Regulation in Canada and Europe, GAO, 1994. GAO Archive.

United States, Congress, House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Government Reform. “Testimony of Mylan CEO Heather Bresch before the United States House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Government Reform”, 2016.

Vogel, Ronald J. “Pharmaceutical Patents and Price Controls.” Clinical Therapeutics 24.7 (2002): 1204-222. Web.