Impact Investments: Good Profits?

By: Genevieve Crawford

Investors with high ethical standards can be constrained by the corporation’s duty to maximize shareholder profit. Pure nonprofits may disappoint with their low returns. A new way of doing good and making money is called impact investing.

Impact investments provides funding opportunities for both social and financial returns. The main advantage of impact investments is its ability to capitalize on governments’ and charities’ lack of monetary resources. As a financial method, it has tremendous potential to solve pressing world issues. Impact investing is already delivering positive outcomes in sustainable development and alleviating poverty (Fox, 2014). Impact investing also offers investors an opportunity to tap into new markets and gain uncorrelated returns on an alternative investment. Despite its obvious benefits, there are numerous hurdles. The problems are: (1) a lack of investment ideas for providing both social and financial returns, (2) an opaqueness in measuring impact and hence, (3) difficulty in deriving a due diligence process for fund allocation, and (4) asymmetric information problems, particularly moral hazard.

Corporations are major players in impact investing. Companies can do so much for the industry through their capacity to deploy funds. Although corporate social investment is a relatively new concept, direct and indirect investment vehicles have been used successfully. These vehicles include social impact bonds and corporate venture capital.

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) refers to a company’s initiative to take responsibility for its actions and their subsequent effects. CSR strategies ensure compliance with ethical standards. Usually, companies allocate funds to CSR policies by promoting sustainable business practices and making charitable donations. While CSR actions are nonetheless worthwhile in an ethical sense, companies should consider impact investments rather than grants and donations to satisfy shareholder demands. By aligning CSR with social investments, companies can create value for both the shareholders and society at large (Claire Kearney, 2016).

Utilitarianism is a moral theory focused on maximizing overall utility for all stakeholders involved in an action. It is opposed to the theory of egoism, an idea that people should pursue their own self-interests, even at the expense of others. If viewed in a utilitarian sense, impact investing is a perfect example of economic efficiency. Pareto improvement arises when an economic action results in a net welfare gain. ‘Economists talk all the time about a ‘Pareto improvement’, which means something that leaves no stakeholder worse off and leaves some stakeholders better off,’ says Larry Summers, former US Treasury Secretary, speaking of Social Impact Bonds (SIBs). ‘This is ground zero of a big deal.’ (Claire Kearney, 2016)

Social Impact Bonds

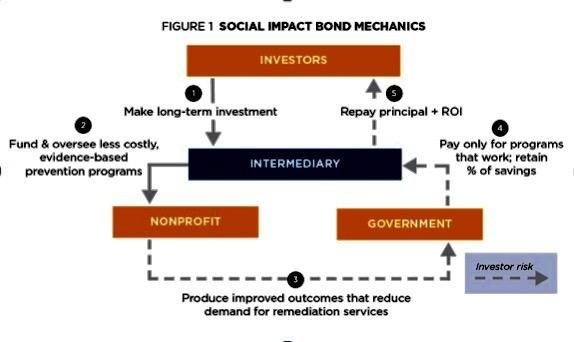

A Social Impact Bond (SIB) is an impact investment financial instrument. It is a pay-for-success contract that compensates investors with financial returns based on the difference created by a nonprofit organization. The idea is a government or private entity contracts to pay for social outcomes that generate future cost saving or value creation. The investor’s funds assist an organization dedicated to achieving social outcomes (Stanford Graduate School of Business, 2015). If the social outcomes are achieved over the threshold specified in the contract, the government or private entity will compensate the investors with the principle and any additional financial returns.

Advocates of SIBs claim there are several beneficiaries from their use. For investors, SIBs offer an uncorrelated investment option, an alternative to the market. Additionally, SIBs provide investors an opportunity to achieve the intangible aspect of positive social outcomes. For governments, SIBs shift the risk of paying for inefficient services onto investors. If the firm does not achieve the outcome level specified in the SIB contract, investors bear the loss. This ensures governments do not waste financial resources on unsuccessful projects. If the company investing money in an SIB ensures the bond is aligned with their CSR strategy, the failure of the investment can be considered as a sunk cost. However, if the investment succeeds, the company gains a financial return on top of positive social impact.

SIB to Reduce Reconviction Rates

In 2010, the first SIB, the Peterborough Social Impact Bond, was launched in the United Kingdom. Social Finance, a not-for-profit financial intermediary, fostered the Peterborough SIB by raising investment funds from individuals, trusts and foundations. The bond funded the intervention called One Service operating at Peterborough Prison. One Service provided support to adult male offenders who served less than 12 months in the jail. The aim of the intervention was to reduce repeat offenses. With this SIB, the Ministry of Justice entered into an agreement to pay returns to investors if the reconviction rate is reduced by more than 7.5% relative to the comparable national baseline. In 2014, results for the first cohort of 1000 prisoners on the Peterborough SIB demonstrated an 8.4% reduction in reconviction events (Emma Disley, 2015).

Although the Peterborough SIB made it relatively easy to calculate impact (i.e., based on reconviction rate), SIBs relating to environmental change or general social welfare are more complex. An issue with SIBs, and impact investing in general, is the difficulty of measuring impact itself. A potential investor needs to measure impact in order to assist with investment selection, evaluate progress of the project, and for reporting purposes. To accurately measure social impact, one must move beyond considerations of whether the originally identified problem improves. It is important to also acknowledge: (a) what would have happened anyway (deadweight), (b) the actions of others (attributions), (c) when the social impact will likely reduce over time (drop off) and (d) positive or negative unintended consequences (Dr Lisa Hehenberger, 2015).

Not all is rosy with SIBs from an investor’s perspective. The impact of the SIB may take years to take effect. This means investors do not get an ongoing dividend. An important aspect of SIBs is the firm’s reliance on continuous investment for adequate working capital (Stanford Graduate School of Business, 2015). At this stage, the limitations in the SIB structure include a lack of standardization, accessibility, liquidity and transparency. As SIBs have emerged as private contracts, there is inconsistency with reporting and a lack of market data. To build a successful market for SIBs, there needs to be an expansion beyond government issuance, where private entities guarantee the repayment to investors. There also needs to be an established standard financial instrument to increase transparency and liquidity (Morrison Foerster, 2014).

Venture Capital

Corporate social venture capital refers to the acquisition of firms that create social impact. Generally, the impact is aligned with the core business of the company. Google Ventures is a venture capital fund invested in more than 300 companies to create social impact. These investments are, ‘in the fields of life science, healthcare, artificial intelligence, robotics, transportation, cyber security and agriculture. [The] companies aim to improve lives and change industries.’ (Google Ventures, 2016). For example, Google Ventures invested in Flatiron Health, a company that organizes medical information on a common software infrastructure. This allows doctors and researchers to communicate and discuss the delivery of suitable patient care (Flatiron, 2016).

(Bridges Ventures, The Parthenon Group, 2009)

There is a clear element of self-interest behind Google Ventures, as most future investments are in areas related to Google’s core business. This characteristic by no means detracts from the fact that Google Ventures is creating welfare for society. While there is a clear return for Google, the main reason for their venture capital is to assist social impact firms who otherwise would not receive funds (Roper, 2014). This in itself creates a social impact. Additionally, Google is strengthening a competitive advantage in the market.

Financial Returns Versus Social Good

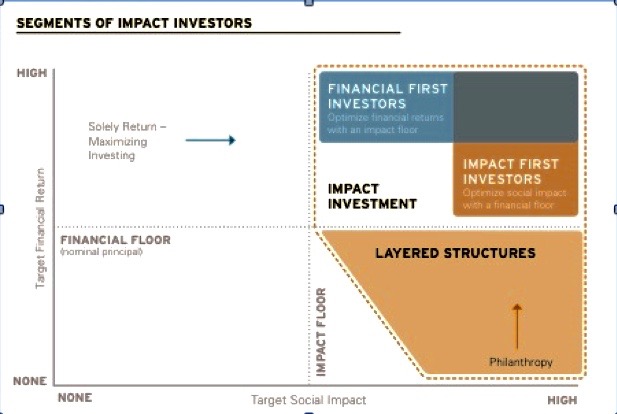

There is an obvious spectrum for impact investments. Although impact investors share a vision of creating social and financial returns, they are generally outcome biased. That is, investors decide whether they are more focused on achieving a financial return or a social initiative. The difference between financial-first investors and impact-first investors is the latter is willing to sacrifice returns for social good. Financial-first investors are not willing to accept below market returns.

The two impact investment viewpoints stand in juxtaposition. Consider the Triodos Renewable Europe Fund active in renewable energy investments since 2006. The open-ended fund contributes to an increase in supply of solar and wind energy to reduce carbon emissions in Europe. In 2015 the fund made a 4.1% average return (Tridos Investment Management, 2015). While it has social initiative, the fund is biased towards financial gain. In contrast, Aavishkaar Venture Management Services, a fund that targets rural poverty in India. Despite its hugely successful impact in low-income areas, Aavishkaar offers a below market return for venture capital investors (Bridges Ventures, The Parthenon Group, 2009).

Despite the market for corporate venture capital in impact groups, there is still a desire for venture capital with nonprofit organizations. Y Combinator, a renowned tech venture capitalist that has funded companies such as Airbnb, Dropbox and Reddit, has also started up a nonprofit program. Since 2013, Y Combinator has funded numerous start-ups such as One Degree. One Degree is a website that helps people find social services like affordable housing and job advice. This service is useful for young adults; particularly those who have grown up in a foster home trying to make it in the world. In 2016, One Degree managed to raise $1.7 million from national donors. While impact funds are on the rise, organizations may successfully obtain capital without any promise of financial return. This is one aspect of venture capital that will not change in the years to come.

Issues in Impact Investing

Greater Scope of Due Diligence

As with any investment, a due diligence process determines suitability. First, this requires reflection on what sort of social or environmental change the company wishes to seek. For institutional investors, the first box is ticked if the investment fund aligns with their CSR strategy. For example, a company like Volkswagen is more inclined to invest in an impact fund with an environmental initiative rather than a reconviction intervention. This potentially helps the future profitability of a company by affiliating investments with long-term goals of the firm. The second step is to determine the desired level of financial reward. If the institution accepts below market returns or is willing to take on more risk, that institution can, and should, use impact focused funds.

There are aspects of the impact investment decision process that decrease its appeal. According to Paul Brest, Professor and Dean Emeritus of Stanford Law School “If you’re doing pure philanthropy you do due diligence to see whether it is a good non-profit organization. If you’re doing pure investment you do due diligence to see if it is solid and will bring a financial return. If you are doing impact investing you are going to have to do due diligence for both of those, which makes it tougher.’ (Stanford Graduate School of Business, 2015) The due diligence process to determine a successful impact investment is longer, as more aspects not usually considered in a traditional donation or investment need to be brought to attention. This extra consideration may be unattractive to investors, despite potential gains.

Poor Outcomes on Both Ends

The other issues in impact investing emerge from asymmetric information, starting with the two extremes. The first extreme is an investment project, which combines the misuse of funds provided with some element of goodwill. Ordinarily well intentioned, these investments can nevertheless be characterized as, ‘Trust me. I’m a good guy. I have good intentions — and I’m going to burn through your money.’ Naturally, badly managed investments are not unique to impact investment alone. The other extreme is when the investment fails, not financially, but on the social impact end. Either the investment or the investor must resort to post-rationalization of an economics-only business model. ‘I have no intentions but look I’ve created jobs, ex post’ (Fox, 2014). Both asymmetries are prevalent in the marketplace, and by their nature impede the expansion of impact investment.

Dearth of Investments

It is still the early days of impact investing. While the idea behind aligning social and financial returns is desirable, there may not be enough investment ideas that are successful and sustainable. No companies, only banks and governments, have issued SIBs and guaranteed thresholds to investors thus far. This is an avenue of financial innovation we may see in the next few decades. For instance, companies may issue SIBs as an opportunity to diversify their investment portfolios. Alternatively, they may create a new share class separate from the firm’s standard stock, which could raise capital purely by issuing an SIB, rather than combining the activity with their common stock holders. No one seems certain about the future of impact investment.

But Worth a Try

In this age, we forget Pareto improvement is attainable. Yes, impact investing may potentially result in losses for investors. But this is beside the point. If corporations pioneer impact investing to achieve their CSR strategies, companies will be introduced to a new avenue of social impact. While shareholders may bear the burdens of impact investment losses, this result is a vast improvement from a company’s usual CSR practice of issuing unprofitable grants and donations. With potential financial returns to please their shareholders, overall utility is increased. While there are elements of impact investment that are problematic, these are not insurmountable. An increase in standardization, accessibility, liquidity and transparency allows companies to involve themselves in impact investing. The field offers opportunities for impressive economic innovation.

Editor: Eric Witmer

-x-

Bennett, J. (2005). Groundwork for the Metaphysic of Morals By mmanuel Kant . Retrieved January 20, 2017, from http://www.earlymoderntexts.com/

Bridges Ventures, The Parthenon Group. (2009). Investing For Impact: case studies across asset classes. Bridges Ventures, The Parthenon Group.

Claire Kearney, M. R. (2016). Corporate Social Investment: Gaining Traction. Oliver Wyman, Big Society Capital.

Dr Lisa Hehenberger, A.-M. H. (2015). A practical guide to measuring and managing impact. European Venture Philanthropy Association. European Venture Philathrophy Association .

Emma Disley, C. G. (2015). The payment by results Social Impact Bond pilot at HMP Peterborough: final process evaluation report The payment by results Social Impact Bond pilot at HMP Peterborough: final process evaluation report. RAND Europe. London: Ministry of Justice Series.

Flatiron. (2016). Retrieved January 24, 2017, from https://www.flatiron.com/

Fox, J. (2014, September 16). What Good is Impact Investing? Retrieved January 12, 2017, from Harvard Business Review: https://hbr.org/2014/09/what-good-is-impact-investing

Google Ventures. (2016). Retrieved January 24, 2017, from http://www.gv.com/

Hartley, J. (2014, September 15). Social Impact Bonds Are Going Mainstream. Retrieved Feburary 19, 2017 , from Forbes: http://www.forbes.com/sites/jonhartley/2014/09/15/social-impact-bonds-are-going-mainstream/#41983ec117d5

Morrison Foerster. (2014). Corporate Social Responsibility, Social Impact Investing and Green Bonds . Morrison Foerster.

Roper, S. (2014, July 12). How Google venture capital will help Europe’s risk-taking techies . Retrieved January 22, 2017, from The Conversation: http://theconversation.com/how-google-venture-capital-will-help-europes-risk-taking-techies-29108

Stanford Graduate School of Business . (2015, August 25). Paul Brest: Impact Investing and Social Impact Bonds. Retrieved January 20, 2017, from Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xr3NCQ1OIag

Tridos Investment Management. (2015). Triodos Renewables Europe Fund Annual Report 2015 . Retrieved January 30, 2017, from Tridos Investment Management: http://www.jaarverslag-triodos.nl/en/tim/2015/tref/servicepages/ataglance.html

West, H. R. (2016). Utilitarianism . Retrieved January 31, 2017, from Encyclopædia Britannica: https://www.utilitarianism.com/utilitarianism.html

Photo: Courtesy of Alphamundi.ch