Hikvision and Dahua: The Case for Divestment

By: Ludovico Picciotto

Financial institutions that defy socially responsible conduct risk punishment by woke consumers and investors. A primary goal of socially responsible investing (SRI) should be to avoid complicity: if a shareholder invests in a company that engages in unethical conduct, that shareholder becomes a supporter – whether active or passive – of that conduct.

The case for divesting Hikvision (002415:CH) and Zhejiang Dahua Technology (002236:CH) shares rests on arguments that: (1) the two Chinese companies are complicit in China’s human rights abuses against Uighers, (2) the investors, by holding shares in Hikvision and Dahua, are complicit too, and (3) it is morally right to divest from shares of Hikvision and Dahua. Some context is necessary.

A Brief History of Human Rights Violations against Uighurs in Xinjiang

In Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region (XUAR) of Northwestern China about 45% of the population– almost 9 million people – are Uighurs. This Muslim, Turkic speaking ethnic group has historically resided in the region, which they call East Turkestan. What’s behind the name? Uighurs’ political struggle for independence or, at least, for autonomy from China.

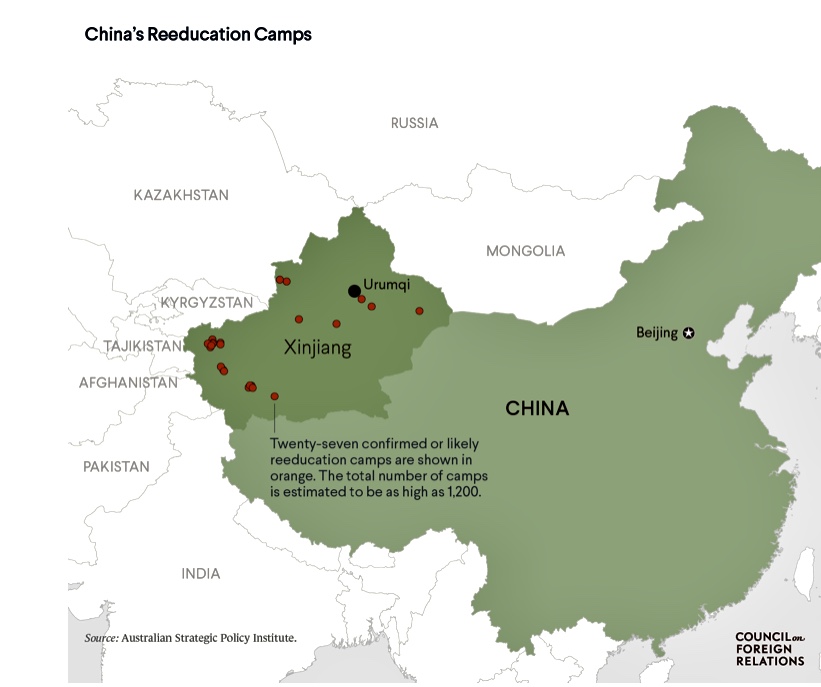

From 2014, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) intensified the oppression of Uighurs under the pretext of the “Strike Hard Campaign against Violent Terrorism”. The Chinese government has been widely accused of ‘cultural genocide’ against the Muslim ethnic minority. In support of the claim, accusers point to the notorious ‘re-education camps’ where more than one million Muslims have been arbitrarily detained.

https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/chinas-crackdown-uighurs-xinjiang

The main purpose of the Chinese crackdown and of the camps is to Sinicize Xinjiang. In the camps, detainees are tortured and forced to pledge allegiance to the CCP, renounce Islam and embrace Mandarin as their first language (Maizland 2019).

Orwellian Dystopia: The Role of Tech Companies in China’s Oppression Machine

The re-education camps are the apotheosis of a systematic, omnipresent crackdown on Uighurs by Chinese authorities. In Xinjiang, more than in the rest of China, the people are victims of a mass surveillance system which not only violates human rights but also Chinese laws (Human Rights Watch: China’s algorithms of repression 2019). Human Rights Watch published an extensive report that explains how the system operates. Briefly, Chinese authorities developed a predictive policing application – the Integrated Joint Operations Platform (IJOP) – that fulfills three main functions: “collecting personal information, reporting on activities or circumstances deemed suspicious, and prompting investigations of people the system flags as problematic” (HRW 2019).

Through advanced monitoring devices, the IJOP algorithms cross-analyze an incredible amount of personal data (consumption patterns, movements, social interactions, emails, texts, height etc.) to discern which suspects to interrogate and detain (Rollet 2018).

Chinese tech companies are instrumental to providing devices and software for the IJOP. In particular, two companies – Hikvision and Dahua Technology – agreed on a $1.2 billion contract with Beijing to furnish and install “not only security cameras but also video analytics hubs, intelligent monitoring systems, big data centers, police checkpoints, and even drones” (Rollet 2018). Both Hikvision and Dahua, the two largest security camera manufacturers, are key in China’s Big Brother dystopia in Xinjiang – a Foreign Policy report explains. In short, as an article in the Washington Post concludes “the surveillance state that Beijing has established in Xinjiang would not be possible without the companies’ help”.

Publicly disclosed contracts between the Chinese government and Hikvision and Dahua (Source: https://ipvm.com/reports/xinjiang-dahua-hikvision)

Financial institutions investing in Hikvision and Dahua

The Financial Times reported “a fifth of about 189 of the world’s largest emerging market funds held Hikvision stock last November…placing the company in the top three most favoured A-shares”. Funds include pension funds, notably The California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS) which owns more than 4.3 million shares in Hikvision, but also ESG Funds like the Candriam ESG Fund.

Furthermore, A-Class shares from both Hikvision and Dahua are part of the MSCI Emerging Markets Index. Hence, investing in MSCI means investing in the Chinese companies.

Recently, the companies suffered a minor blow in the stock market as public indignation of Uighur oppression punished the two giants, perceived as CCP accomplices. Especially in the US, efforts in Congress nurtured public opinion against the two businesses causing several US equity funds to divest. Nonetheless, greed seems to trump morality as new and old investors are enticed by the companies’ high profits, which overshadow even ESG Funds’ ethical concerns.

The question is: in the light of these facts, are financial institutions complicit in human rights violations? Accordingly, should they divest from Hikvision and Dahua?

Degrees of Complicity

Despite clumsy efforts from the CCP to disguise its re-education camps as ‘vocational camps’ and allegations of gross human rights violations as ‘Western fake news’, the facts reported in the article are well-documented.

Less certain are the two Chinese companies’ kind and degree of complicity in Uighur oppression. Even more blurred is their shareholders’ responsibility. Establishing the kind and degree of complicity of both groups of actors is imperative to assess the morality of investor responses to the crisis. Establishing complicity is a two-step process: first investigators need to prove Hikvision’s and Dahua’s complicity before establishing their shareholders’ complicity. If the two businesses are not complicit, then shareholders are absolved too.

Corporate Complicity in Human Rights Abuses

The fundamental meaning of ‘complicity’ is ‘collusion in a wrongful act’, but precise definitions of the concept vary according to context. This is important for the moral disquisition that follows because we can interpret complicity legally and/or morally. The article will judge the moral complicity of businesses and financial institutions, foregoing discussions on their legal complicity. Nonetheless, this is not an arbitrary exclusion and we need to present the rationale for discounting legal complicity.

Put simply, in Public International Law (PIL), human rights violations can only be committed by States and by individuals in the very limited circumstances enshrined in the Rome Statute. This is because human rights treaties are negotiated and signed/ratified by State parties, thus only the abstract entity of the State can breach the content of the treaty. Nonetheless, the state-centrism of PIL has come under threat especially in substantive fields such as the International Human Rights Law (IHRL), which has pioneered a doctrinal shift from the State to the individual and groups. Albeit these efforts are increasingly changing the nature of IHRL, the field remains heavily state-centered and excludes the possibility of complicity in human rights abuses for corporations. The debate surrounding the ‘responsibility’ of corporations under IHRL is constantly evolving and complex: “there are no general rules or principles that determine to what extent companies can be held ‘responsible’ for human rights abuses” (Nytsuen 2011, 17). Thus, a disquisition on the legal dimension of corporate ‘complicity’ would lack a strong conceptual basis.

In ethics too, the concept of complicity is debated and complex (for an authoritative study of the concept we point to Gregory Mellema’s Complicity and Moral Accountability). Not only the degree of complicity can vary, but also its kind. It is important to understand complicity qualitatively and quantitatively to assess an entity’s moral accountability. In The Morality of Divestment, Professor Jeremy Moss – an expert in applied ethics – gives a simple yet exhaustive definition of complicity:

“an agent is complicit when they knowingly assist or encourage the harms of others. Through involvement in the harms of others (i.e., harms committed by the primary or principal agents), a secondary agent becomes an accomplice or accessory and, in standard cases, shares some of the liability for the harms done. The harm committed by the secondary agent is usually said to derive from the harm committed by the primary agent. Secondary agent can be complicit in different ways, including by actively conspiring and planning a harm with a principal agent; by simply cooperating with the agent; by encouraging, permitting, or soliciting harm by the agent; or by aiding and abetting the agent” (Moss 2017, 416)

The severity of the complicity depends on its type and magnitude. In the next two sections we explore the degree and type of complicity of Hikvision and Dahua first, and of their shareholders, second.

Hikvision and Dahua Complicity

The products and services of the two Chinese companies are pivotal for the IJOP. The organization uses their mass surveillance applications to help Beijing identify purported suspects. In short, by accepting rich contracts with the government to monitor and control people in Xinjiang, the two companies are enabling the current system of oppression in the region. Certainly, the companies are not themselves the perpetrators of human rights violations, but, given their centrality in the project, they are complicit in the violence. Obviously, the two tech companies are not the only businesses in the Chinese market, although they are the biggest ones, and the Chinese government could have stipulated a contract with other providers. Regardless, at the moment the two tech giants are providing goods and services to the government and are thus secondary agents cooperating with the primary agent (the CCP) in the repression of Uighurs in XUAR. Furthermore, although there are no reasons to believe that Hikvision and Dahua have the same motivation as Beijing, we can safely assume they are aware of the government’s intentions.

Summing up, Hikvision and Dahua: 1) have been and will be instrumental and necessary for the current system of oppression but are not the direct perpetrators of the violence; 2) had prior knowledge of (or the possibility of acquiring prior knowledge of) the way in which their goods and services would have been employed by the government. Hence, Hikvision and Dahua are direct accomplices to the human rights abuses against Uighurs because they – in the words of the UN Global Compact – “provide[d] goods or services that [they knew] will be used to carry out the abuse”.

Hikvision and Dahua Shareholders’ Complicity

Having established the complicity of the two companies, we need to understand if and how the financial institutions investing in these businesses can be considered complicit. Firstly, we need to understand whether shareholders could have known that Hikvision and Dahua were involved in human rights abuses. Second, there is the more difficult matter of establishing whether and in what way investors contribute to the violence as well.

As per the first matter we can concisely affirm that financial institutions investing in Hikvision and Dahua had access to numerous authoritative reports on the human rights situation in Xinjiang and the complicity of the two companies. Now, we need to establish whether investing in these businesses with prior knowledge of their unethical conduct makes the investor an accomplice.

According to Ingierd & Syse (2011), the investments from financial institutions are materially significant to companies in at least four ways (obviously, the impact depends on the size of the investment):

First, the investor contributes especially secure and predictable form of financing.

Second, the investor becomes a part owner of the company, with all the rights associated with that. This includes, even if only in a limited fashion, a say over the actions, direction and future of the company.

Third, an investor – and especially a large institutional investor– gives the companies in which it invests a certain financial and/or moral legitimacy by placing its funds there.

Fourth, making an investment creates a precedent. Thus, one’s investment in a certain kind of product, company, sector or market may create a greater likelihood that similar investments will be admitted into the fund

Each of these four points represents a causal link between the shareholder and the unethical act in question. They demonstrate that owning shares in a business that violates human rights makes an investor a direct accomplice because of the causal link.

Even if the four points do not apply, investors can still be considered indirect accomplices because: “by placing one’s money in a company, expecting that company to maximize (or at least secure) returns on one’s investment, one also helps direct what the company actually does.” (Ingierd & Syse 2011, 163)

The investors are thus at best indirectly complicit and at worst directly complicit (this depends on the size of the investment, the influence of the financial institutions etc.).

Moral Arguments for Divestment

Deontological Argument

The theory of deontology states we are morally obligated to act in accordance with a certain set of ethical principles regardless of outcome. This approach is a duty-based theory because we are duty bound to act in accordance to moral principles and rules. It is a moral principle in all cultures to not harm another human person. Accordingly, investors are obliged to adhere to this principle in order to act ethically.

Thus, financial institutions should divest from Hikvision and Dahua because owning their shares makes the finance firms complicit in human rights abuses in the ways we have shown previously. Virtually every financial institution’s code of ethics has provisions condemning the institution’s participation in human rights abuses. So does every state we know of (including China) and so does the UN Global Compact, a non-binding pact that provides a set of ethical guidelines for business and financial institutions. By adopting deontological conceptions of ethics, divesting is right because it means ceasing to be complicit in a wrongful act. The argument here is twofold: divesting stops the promotion of injustice and harm and safeguards the integrity of the financial firm by aligning its values with its actions.

Consequentialist Argument

The second argument in favor of disinvestment is a consequentialist argument. Consequentialism proposes the outcomes of an action are all that matter when taking an ethical decision to act. The rightness or wrongness of an action depends on the consequences of the act. For classical utilitarianism, the most common form of consequentialism, the desired outcome comes from creating the most good for the most people or maximizing the overall good.

Therefore, divesting is right because it would have overall positive consequences, in regards to the legitimacy the financial institution and the situation in Xinjiang. Indeed, divestment, especially if sizeable, would contribute to spreading awareness on the human rights abuses in which Hikvision and Dahua are complicit. This delegitimizes the perpetrators and encourages and pressures other institutions to act in similar fashion. Furthermore, divesting could be right in a utilitarian sense because the loss of welfare caused by complicity in the Uighur human rights crisis outweighs possible economic gains through investing in Hikvision and Dahua. In the utilitarian ranking of outcomes, saving, or not harming human life outweighs financial gains.

Objections to Divestment

While divestment seems the best way to ‘make it right’ since both duty based and consequentialist ethical theories agree on the correct action to be taken, some may still argue it is a less satisfactory ethical choice. The financial institution is absolved from moral claims upon divesting shares of Hikvision and Dahua. Arguably, the financial institution also washes its hands of the human rights problems it faced as a shareholder. Divesting might be deontologically right because the institution no longer participates in breaking ethical principles such as “do not harm other humans”. Yet, it might not be effective from an activist point of view, in improving the situation in Xinjiang. The institution should make a deliberate effort towards halting cultural genocide in the region by exercising active ownership (Nytsuen 2011). The rationale is that “investors could, at least in theory, exert greater influence on businesses from the inside, and potentially push companies to act in more ethical ways”, as Andrew Davenport, chief operating officer of RWR Advisory, a risk-management firm, told MarketWatch. Engagement with companies through dialogue and exercise of ownership rights, with the aim of improving company conduct, is a far more common approach to ethical challenges. Once a financial institution divests from a company, it also loses the leverage it had through its ownership rights vis-à-vis that company (Nytsuen 2011).

Refutation of the Divestment Objection

Shareholder activism is praiseworthy if the shareholder is pushing for the company to enact rules to protect the environment or to improve on certain behaviors. However, activism will do little to change the actual product or services offered by a company. In this case, Hikvision and Dahua provide surveillance equipment and software. Activism will not make the companies change their product offerings because doing so would mean an end to their existence as providers of surveillance equipment. Not funding the companies and blacklisting them is likely more effective in changing their business model.

Divest For the Good

In this specific case study, China’s human rights abuses against Uighurs people in Xinjiang are systematic and grave, and Hikvision and Dahua are directly complicit in the abuses. Consequently, even if divestment might be a choice dictated by political or economic self-interest, it is morally upright. This conclusion can be reached both from a deontological and from a consequentialist conception of ethics. Deontologically, divesting would be right because it would bring back the financial actor within certain moral standards – whether we take them to be the UN Global Compact, its own code of ethics, or the state’s laws and public morals. Teleologically, it could potentially be right because of ripple effect that divesting could have: it would bring awareness to the cause, delegitimize the two Chinese companies and spur other financial institutions to divest too.

The argument that divesting could have negative repercussions on the financial performance of investors and on the people and communities with a stake in the Chinese tech businesses is easily refuted. In addition, for financial institutions, the investments in one company is relatively small in relation to the other investments. Fundamentally, in computing a welfare assessment, human rights abuses entailing physical and psychological harm outweigh economic benefits.

The alternative to divesting could be exercising pressure from the inside, by exploiting ownership rights to persuade the businesses to change their behavior. However, the capacity among foreign investors to guide the reform of a Chinese state-owned firm is woefully limited.

In sum, not only both teleological and deontological arguments for divestment are valid but the arguments against divestment are weak. Ultimately, divesting is the best ethical alternative.

Editor: Kara Tan Bhala

REFERENCES

BBC. (2016, November 17). Xinjiang profile – full overview. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-pacific-16913494

Chesterman, S. (2007). “The Turn to Ethics: Disinvestment from Multinational Corporations for Human Rights Violations – The Case of Norway’s Sovereign Wealth Fund.” American University International Law Review 23, no.3: 577-615.

Choi, C. (2019, July 5). China accused of rapid campaign to take Muslim children from their families. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jul/05/fake-news-china-dismisses-reports-about-detention-of-uighurs

H. R. W. (2019, June 25). China’s Algorithms of Repression: Reverse Engineering a Xinjiang Police Mass Surveillance App. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/report/2019/05/01/chinas-algorithms-repression/reverse-engineering-xinjiang-police-mass-surveillance

Ingierd, H., & Syse, H. (2011). The moral responsibilities of shareholders: a conceptual map. In G. Nystuen, A. Follesdal, & O. Mestad (Eds.), Human Rights, Corporate Complicity and Disinvestment (pp. 156–182). chapter, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. http://doi.org.gate3.library.lse.ac.uk/10.1017/CBO9781139003292.009

Mellema, G. (2016). Complicity and moral accountability. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

Moss, J. (2017), The Morality of Divestment. Law & Policy, 39: 412-428. doi:10.1111/lapo.12088

Nystuen, G. (2011). Disinvestment on the basis of corporate contribution to human rights violations: the case of the Norwegian Government Pension Fund. In G. Nystuen, A. Follesdal, & O. Mestad (Eds.), Human Rights, Corporate Complicity and Disinvestment (pp. 16–43). chapter, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. http://doi.org.gate3.library.lse.ac.uk/10.1017/CBO9781139003292.003

Oh, S. (2019, May 30). ‘Socially responsible’ investors may have unwittingly backed police-state surveillance in China. Retrieved from https://www.marketwatch.com/story/socially-responsible-investors-may-have-unwittingly-backed-police-state-surveillance-in-china-2019-05-30

Principle 2: UN Global Compact. Retrieved from https://www.unglobalcompact.org/what-is-gc/mission/principles/principle-2

Riding, S. (2019, June 1). Candriam ESG fund defends its holding in Chinese surveillance group. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/3ea09c51-0354-33a3-9a2f-4292b2d30c59

Rollet, C. (2019, July 23). In China’s Far West, Companies Cash in on Surveillance Program That Targets Muslims. Retrieved from https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/06/13/in-chinas-far-west-companies-cash-in-on-surveillance-program-that-targets-muslims/

Sevastopulo, D. (2019, March 29). US pressure building on investors in China surveillance group. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/36b4cb42-50f3-11e9-b401-8d9ef1626294

Smith, M. (2019, April 17). Buying stock in these Chinese companies makes you complicit in terror on Uighurs. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/global-opinions/think-twice-about-your-investment-portfolio-it-likely-undermines-human-rights-in-china/2019/04/17/a981b85a-6125-11e9-bfad-36a7eb36cb60_story.html?noredirect=on

U. N. P. O. (2015, December 16). East Turkestan. Retrieved from https://unpo.org/members/7872