Higher Interest Rates In Australia: Burdens and Rewards

By Zachary Hazel

The burdens of higher interest rates in Australia weigh down the least financially able, while the rewards benefit the economically advantaged. This outcome strains the principles of distributive justice.

A key economic goal of any economy is to have a ‘low and stable’ inflation rate, generally in the 2-3% range. This level of price increases promotes economic stability, growth, and enables people to make financial decisions with greater confidence. Over the past three decades, on average, Australia met these inflation targets. However, following the economic upswing post COVID-19, Australia has experienced record inflation. This and attendant high interest rates result in winners, losers, and ethical issues.

Inflation refers to an overall increase in the price of goods and services within an economy over a period. It limits both business and consumer purchasing power. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) measures inflation, calculating the percentage change in price of goods and services across consumption categories, from one period to the next.

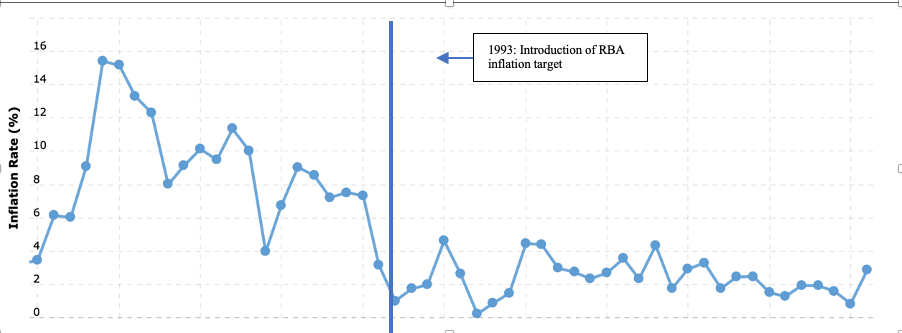

Following severe unemployment accompanied with high rates of inflation throughout the 1970s, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) introduced an inflation target of 2-3% in 1993. The target allows for stability and ensures businesses and consumers can confidently plan. Stable, low inflation encourages people to spend given expectations of future price increases, and results in economic growth. As evident in Figure 1, Australia has consistently met this target for the best part of three decades.

Figure 1: Australia’s inflation rates (1970-2021, measured by CPI)[1]

Source: macrotrends

Despite fluctuations in and out of the 2-3% target post 1993, there exists a far more stable inflation rate. Australia has successfully met inflation targets with an average of 2.4% inflation from 1993 to 2021.

However, following a strong economic recovery post COVID-19 lockdowns, Australia reached an inflation rate of 7.3% in September 2022, its highest level since June 1990.

This raises the question, what caused the steep inflation increase?

The initial answer relates to demand. Global travel restrictions, the introduction of government COVID relief welfare payments and a reduction in interest rates meant Australians had additional money which created an increase in consumer demand. This initial surge in demand was accompanied by recent supply chain issues. The Ukraine war, flooding throughout Australia, and China’s December 2022 COVID outbreak, after three years of a wholly misguided zero COVID policy, made it arduous to meet the rising levels of demand. As such, inflation has increased.

Although the RBA expects inflation to decline during 2023, record inflation produces winners and losers. A high proportion of households become relatively poorer and struggle with mortgage repayments. Inequality rises because poorer households simply lack the savings to meet extraordinary price increases. Yet, despite supply shocks and increased demand being inflationary, many of Australia’s large corporations see an opportunity to increase profit margins, thus further intensifying inflationary pressures.

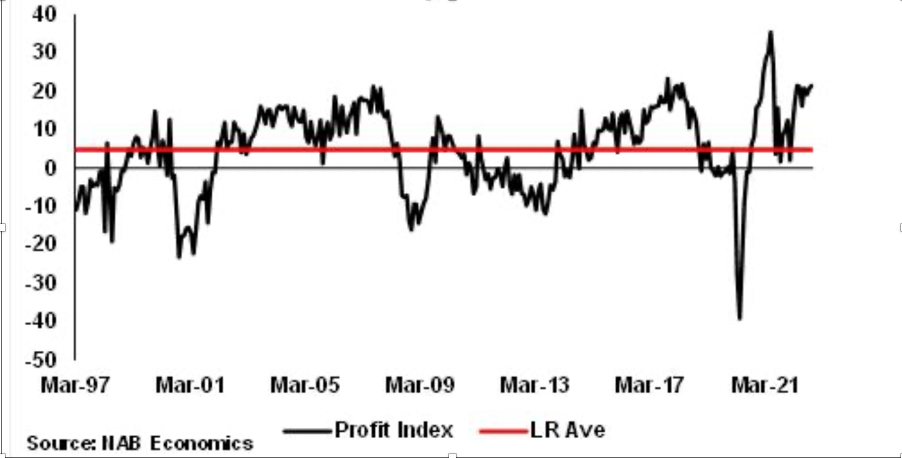

Rewards: Increased Profit Margins for Corporations

Data suggests many corporations have taken advantage of rising inflation to increase profit margins. Throughout 2021, corporate profits increased by 28% and in the words of the executive director of the Australian Institute, Richard Denniss, “firms have never had it so good” (Figure 2).

Figure 2: National Australia Bank (NAB) business survey: profit index

Source: NAB economics

As shown above, business profits are well above the long run average.

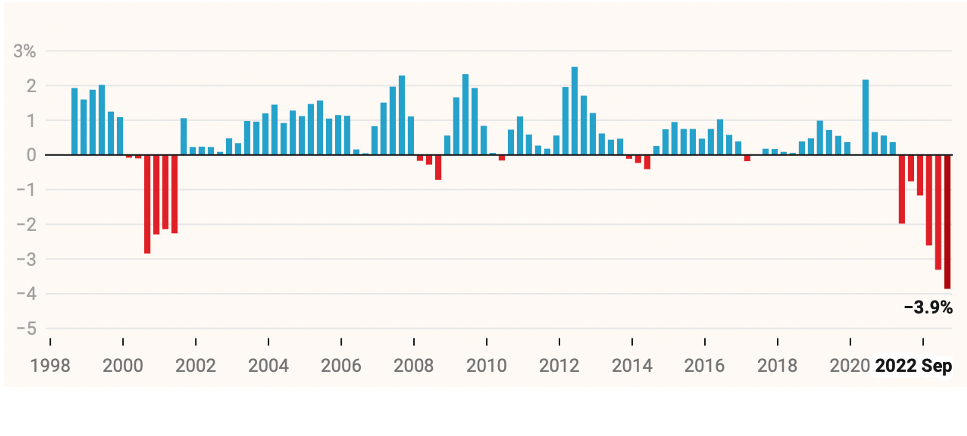

In July 2022, the Australian Institute published a report titled ‘Are Wages or Profits Driving Australia’s Inflation?’ (Denniss et al, 2022). It found company profits have been the main cause of Australia’s recent inflation (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Australia’s GDP deflator (2005-2022)

Source: The Australian Institute

As evident, profits were consistently a large contributor to inflation since 2005 but had a greater impact in the post COVID economy since 2020. In the last 3 years company profits have accounted for 60% of inflation whilst labour costs accounted for 15%. Australian businesses are of course, impacted by an increase in input prices with increased energy costs, a more competitive employment market, and various global supply chain issues. Yet, corporations have been able to increase profit margins because of pent up demand.

The harsh restrictions of COVID meant consumers saved more money because of travel and hospitality restrictions. Additionally, Australia’s unemployment rate is 3.5%, its lowest level in 48 years. Demand remained high allowing businesses to increase prices. Consequently, corporations enjoyed high profit margins without seeing a drop off in demand, but further driving inflation.

Burdens: Decreasing Real Wages for Workers

Although some big corporations are seeing record profits, the average Australian hasn’t had it quite as good. From June 2021 to June 2022 company profits saw a staggering increase of 28%. The same cannot be said for wages which increased a mere 1.9% over the same period. Sally McManus from the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) states “we’ve definitely got a profit crisis at the moment… it’s the reason inflation is so high.” She attributes it to one factor, “greed” (Ziffer, 2022).

While wages are increasing, inflation increases faster, and consumers suffer a drop in real income. Real wages (measured by wage growth less inflation) dropped 3.9% during 2022, the largest decline since the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) began measuring real wages in 1997 (figure 4).

Figure 4: Real wage growth in Australia (1997-2022)

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics

Given this sharp decline, real wages now sit at the same point as in December of 2011. The RBA estimates in 2024, real wages will be 5.4% less than its pre-pandemic rate. In this case, real wages will fall to their 2008 levels and erode more than a decade of real wage growth. High rates of inflation accompanied with a significant lag in wage growth result in a decrease in the standard of living. Richard Denniss from the Australian Institute says the scenario is simple, “there is only one way to increase real wages, and that is for employers to give their employees a wage rise” (Langdon, 2022). The fact that record profits for these corporations have not been accompanied with adequate wage growth is concerning. The lack of wage growth accompanies unfulfilled promises and increasing frustration from the Australian public. Sally McManus from the ATCU states, “we’ve always been told we’re just going to wait for profits to go up … oh we’ve got to get productivity up…then we get told we’ve just got to wait for unemployment to get low” (Ziffer, 2022). Richard Denniss had similar things to say, “unemployment falls, you get a pay rise’, we’ve been told this for 10 years and it hasn’t happened” (Langdon, 2022). Profits are at record highs, productivity is high, and unemployment are at record lows. Yet employees have not seen the promised wage increases.

Worryingly, non-discretionary items, notably food and energy, experience the biggest price increases. For instance, the price of fruit and vegetables increased by 18.6% from August 2021 to August 2022.

Energy Australia, the electric utility, announced an average rate increase of 10% across Australia beginning in August 2022 (Energy Australia, 2022). However, the Treasury has warned the worst may yet come with energy prices expected to increase by a further 50% over the next 2 years (Kennedy, 2022).

In the words of the RBA, Australians’ have “buffers” to help them weather the increase in costs of living, that is savings accumulated during the pandemic (Lowe, 2022). Price increases of essentials have no doubt impacted all Australians, but low-income earners have been most affected. Put simply, these households lack “buffers”, and essentials are taking up an increased proportion of their already limited income. The CEO of the Australian Council of Social Services (ACOSS), Cassandra Goldie states that low-income earners “are absolutely crushed by what’s happening… we are worried about people now living in cars. That’s the reality of what’s happening” (Arora, 2022). Despite this, Australia’s most vulnerable have been overlooked by government. Although the standard rate Jobseeker payment (Australia’s welfare benefit system) increased from $642.70 AUD to $668.40 in September 2022, it adds up to a mere $17,378 annually, still significantly below Melbourne’s poverty line of $28,000 per year. St Vincent de Paul president Claire Victory describes this inadequate assistance as a “lack of understanding, or care, for people doing it tough” (Arora, 2022).

Not only has inflation created severe financial hardship, but mental health issues have also seen a sharp rise in recent years. A survey conducted by Suicide Prevention Australia found upwards of 40% of Australians have experienced increased distress in the past 12 months because of cost-of-living pressures. The survey also found that of the 12 categories, ‘housing access and affordability’ and ‘cost of living and personal debt’ both ranked in the top three most significant risks to suicide.

Reserve Bank’s Role

When referring to inflation, the Reserve Bank’s role is often discussed. In response to inflationary pressures, the RBA increased the cash rate for 8 consecutive months to a 10 year high of 3.1%. The rationale for the aggressive rate increases is to increase the cost of borrowing. Mortgage payments then take up a greater portion of income and thus, higher rates reduce demand. Indeed, economist Callam Pickering says that “households have been hit from every direction, with inflation adjusted wages at an 11-year low, mortgage rates rising, and asset prices falling” (Janda and Whitson, 2022). This parade of horribles follows slow economic growth prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The slow growth led to cash rates reaching a record low of 0.10 % in November 2020 (Figure 6).

Figure 6:

Source: Reserve Bank of Australia

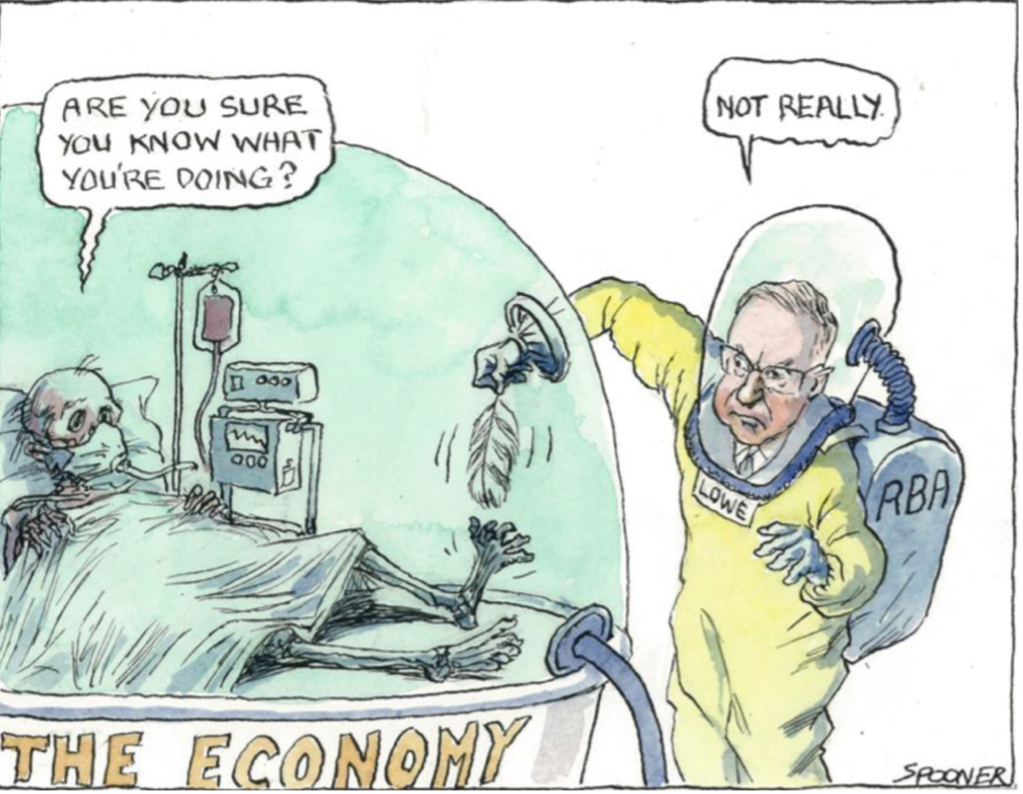

Given the bleak economic outlook at the time, RBA governor Phillip Lowe told the Australian public that the cash rate will remain low until the end of 2024. As such, many Australians elected to take out home loans. This comment was made just months prior to the beginning of 8 consecutive increases in the cash rate. His lame response was, “I am sorry that people listened to what we’ve said and acted on that, and now find themselves in a position they don’t want to be in” (Read, 2022).

Figure 7: Lowe’s comments have been accompanied with increasing frustration from the Australian Public

Source: The Australian

Burdens: Increasing Property Unaffordability

A recent report released by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) titled ‘Housing Market Stability and Affordability in Asia-Pacific’ presents concerning data for the Australian property market. The report describes Australia’s property market as one of the most ‘misaligned’ in the world in reference to affordability. The average household would have to spend greater than 40% of its disposable income to afford a median priced property, well above the average of 20% for Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. Australia has seen problematic increases in the “housing cost overburden rate” i.e., the percentage of the population spending 40% or more of their income on housing. As a result of this “misalignment”, the report suggests Australia’s property market is at the brink of collapse. The report states, “a high magnitude of price misalignment, when combined with the impacts of high policy rates, can lead to a sizeable price correction, nearly comparable to past episodes of housing busts” (International Monetary Fund, 2022). If this were the case, it could leave many Australians’ owing mortgage repayments greater than the house values, saddling them with ‘underwater mortgages.’

Recently the University of New South Wales in conjunction with the Australian Council of Social Services (ACOSS) released a study titled, ‘COVID, Inequality and Poverty in 2020 & 2021’. The study found increasing house prices during the pandemic accounted for 69% of the increase in household wealth (Naidoo et al, 2022). 2021 saw the highest single year increase in housing prices since 1986. This increase widens the wealth gap between those who owned property prior to 2021 and those who didn’t.

This chasm is evident through alarming wealth inequality statistics. The top 10% of households hold 46% of all wealth whilst the bottom 60% of households make up only 17%. The UNSW Social Policy Research Centre (SPRC) director, Professor Carla Treloar states that “this report reminds us that wealth in Australia is distributed very unevenly … we have an economic model that delivers profits for the wealthiest at the expense of those with least in our community” (Kaidoo et al, 2022). For the most part, this widening gap affects young people who are looking to enter the property market for the first time as well as low-income earners. A common measure of wealth distribution is the Gini coefficient. A coefficient of 1 indicates perfect inequality whereas 0 indicates perfect equality. Australia has a coefficient of 0.318, ranked 16th highest of the 38 OECD countries. Although Australia does not rank at the highest in terms of wealth inequality, the figures are still concerning.

While those with lower incomes in Australia deal with rising interest rates, negative real wage growth, limited purchasing power, and increased mental distress, corporations have been able to bring in record profits. The big four banks forecast a considerable decline in inflation over the next two years easing to the 2-3% target range by the end of 2024. However, during this period of high inflation, there has been key shortcomings and a lack of transparency in Australia’s response, and these problems need to be addressed. Most notably, Australians have been given false information about interest rate expectations and have been promised wage increases that failed to materialize. Government seems at best unconcerned or at worst in the thrall of big business.

References

Wealth inequality in Australia and the rapid rise in house prices, UNSW Newsroom. Available at: https://newsroom.unsw.edu.au/news/social-affairs/new-report-wealth-inequality-australia-and-rapid-rise-house-prices (Accessed: December 22, 2022).

Walker, L. (2022) Scarlett can’t work, Can’t get disability allowance and now the cost of living is damaging her mental health, ABC News. ABC News. Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-09-26/new-survey-shows-cost-of-living-biggest-suicide-rsk/101450548 (Accessed: December 20, 2022).

Birstow, M. (2022) CPI forecast australia: When will inflation go down?: Ratecity, RateCity.com.au. Available at: https://www.ratecity.com.au/home-loans/mortgage-news/when-will-inflation-peak-australia-here-s-big-banks-think (Accessed: December 19, 2022).

What is inflation? (2022) McKinsey & Company. McKinsey & Company. Available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/mckinsey-explainers/what-is-inflation (Accessed: December 22, 2022).

Reserve Bank of Australia (2022) Inflation and its measurement: Explainer: Education, Reserve Bank of Australia. Available at: https://www.rba.gov.au/education/resources/explainers/inflation-and-its-measurement.html (Accessed: December 18, 2022).

Reserve Bank of Australia (2022) Australia’s inflation target: Explainer: Education, Reserve Bank of Australia. Available at: https://www.rba.gov.au/education/resources/explainers/australias-inflation-target.html (Accessed: December 23, 2022).

Australia inflation rate 1960-2022 (no date) MacroTrends. Available at: https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/AUS/australia/inflation-rate-cpi (Accessed: December 15, 2022).

Reserve Bank of Australia (2022) Economic outlook: Statement on monetary policy – November 2022, Available at: https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/smp/2022/nov/economic-outlook.html (Accessed: December 28, 2022).

Ziffer, D. (2022) ‘we’ve definitely got a profit crisis’: Is corporate gouging the biggest cause of inflation?, ABC News. ABC News. Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-11-15/profit-crisis-the-inflation-driving-pressure-we-don-t-talk-about/101631802 (Accessed: December 26, 2022).

View, H. et al. (2022) Business research and insights, Business Research and Insights. Available at: https://business.nab.com.au/ (Accessed: December 26, 2022).

Are wages or profits driving Australia’s inflation – the Australia Institute (no date). Available at: https://australiainstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Are-wages-or-profits-driving-Australias-inflation-WEB.pdf (Accessed: December 24, 2022).

Wage price index, Australia, September 2022 (no date) Australian Bureau of Statistics. Available at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/price-indexes-and-inflation/wage-price-index-australia/latest-release (Accessed: December 17, 2022).

Tan, S.-L. (2022) Lettuce at $8? inflation in Australia is hurting everyone from restaurant owners to diners, CNBC. CNBC. Available at: https://www.cnbc.com/2022/10/05/australia-inflation-rising-food-prices-are-hurting-restaurants-diners.html (Accessed: December 21, 2022).

‘people living in cars’: Rising inflation is devastating for low-income earners, community groups say (no date) SBS News. Available at: https://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/people-living-in-cars-rising-inflation-is-devastating-for-low-income-earners-community-groups-say/pl352mxv9 (Accessed: December 24, 2022).

Martin, P. (2022) Unemployed Australians finally get a pay rise larger than pensioners – but it’s a sign of a broken system, Unemployed Australians on JobSeeker are set to break two pay rise records – but it’s a sign of a broken system, long overdue for a fix – ABC News. ABC News. Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-09-07/jobseeker-unemployed-payment-increase-but-under-poverty-line/101411296 (Accessed: December 28, 2022).

Janda, M. and Whitson, R. (2022) Reserve Bank raises rates to highest level in a decade, Lowe expects further increase from here, ABC News. ABC News. Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-12-06/rba-interest-rates-rise/101737682 (Accessed: December 23, 2022).

Wright, S. (2022) ‘I’m sorry if people listened to what we’d said’: Lowe’s sorry excuse for an apology, The Sydney Morning Herald. The Sydney Morning Herald. Available at: https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/i-m-sorry-if-people-listened-to-what-we-d-said-lowe-s-sorry-excuse-for-an-apology-20221128-p5c1um.html (Accessed: December 21, 2022).

“Regional Economic Outlook Asia and Pacific Sailing into Headwinds” (2022) International Monetary Fund (Accessed: December 27, 2022)

Agencies (2022) Australia’s inflation hits 21-year high as food, energy costs explode, Daily Sabah. Daily Sabah. Available at: https://www.dailysabah.com/business/economy/australias-inflation-hits-21-year-high-as-food-energy-costs-explode (Accessed: January 5, 2023).