Fairness Assessment: Australian Housing Tax Subsidies

By: David Charlwood

Introduction

The right to housing is a human right recognised by the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. This basic human right is usually applied to developing countries. Yet, the housing market in Australia, a developed economy, is increasingly difficult to enter as young, aspiring first-home buyers are priced out of the market. This shift is of particular importance in a nation where the idea of owning a home outright is mythologized as ideal, and renting is seen as the refuge of those who ‘haven’t yet made it.” The reasons explaining this instability are multi-factorial. Australian government policy has significantly contributed towards an unsustainable housing market. The two most often mentioned by academics and commentators are negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount (CGT).

Definition of Negative Gearing

In the context of the Australian housing market, negative gearing is a policy which allows investors in residential property (that is, those not intending to live in the property) to recoup some of the expenses paid on this investment. A common example is interest paid on a loan to secure the property. If the interest is more than the annual income generated by the investment, then the interest paid can be deducted from the investor’s other income (such as a salary). This tax deduction reduces her tax liability for that financial year. The reason such an investor is willing to make a short-term ‘loss’ (i.e., paying loan interest) is the hope housing prices continue to increase, which would allow for a large profit once the investment property is sold.

Capital Gains Tax Discount and Home Ownership

At this point the capital gains tax (CGT) discount comes into play. The profits made upon selling are taxed, of course, but only at half the standard capital gains tax rate. Effectively, both policies are tax concessions because the Australian government forgoes a large amount of revenue to promote investment in property. The reason the government does so, on a greater scale than economically comparable countries, goes back to Australia’s post-war economic boom. Land was widely available, and all governments during this period were toying with various social and economic reforms. Subsidising housing at the time led to higher rates of home ownership. Today’s market, with demand for housing far outstripping supply, calls for a re-evaluation of the Australian government’s housing tax concessions.

Unsustainable Housing Market

Whilst these policies may have had good intentions initially, there have been many unfortunate consequences. Speculative property investment has fuelled rapid growth in housing prices (particularly in Melbourne and Sydney). From 2002-2012, average house prices rose by 92% for houses and 40% for flats, while rents rose by 76% for houses and 92% for flats – many times higher than the 31% rise of the Consumer Price Index over the same period (Davidson and Evans). At the same time wages have remained stagnant. Consequently, Australia is now the third least affordable housing market in the world, behind only Hong Kong and New Zealand (Fernyhough). Informed estimates of the cost of both negative gearing and the capital gains discount come to a total of $7.7 billion AUD per year (Grudnoff).

Defence of Existing Policy

Defenders of the existing tax benefits argue these policies increase the attractiveness of investing in the Australian housing market, with raw housing stock numbers increasing as a result. The increase benefits non-homeowners, as more housing supply increases the number of properties available and therefore, applies downward pressure on rental prices. This analysis is true to a certain extent but obfuscates other important economic factors.

Several quantitative studies show that over 90% of investor borrowing to purchase rental properties is for existing housing, not new housing. (Davidson and Evans) Instead of increasing housing supply, investors compete with those intending to buy the property as their primary residence. While it is true rents have slightly reduced due to more rental properties being available, house prices have ballooned due to increased investor competition. Those who own property have been able to ride this surge of capital gains, but for those outside this group (young first-home buyers, financially vulnerable groups such as older single women) the capital gains elevator is sealed. Shut.

Recent Scholarship

A quantitative study released early this year from the University of Melbourne’s Economics Department modelled the effects of removing these policies. The study finds that “removing negative gearing would result in lower house prices, higher rents and home ownership rate” (Cho, Yunho et al.). There is currently policy inertia because no government wants to be responsible for lower house prices (however small they may prove to be). “Improvements in home-ownership rates,” the study finds, “are observed predominantly among young and middle-aged households who are relatively poor” (Cho, Yunho et al.). Overall, the study concludes 76% of households would prefer to live in an economy without negative gearing on residential property (Cho, Yunho et al.).

The following graph illustrates who most benefits from these policies:

Sourced from (Grudnoff)

In the graph, Australia’s population is divided into one-fifth blocks by income, and then compared with the benefits accrued from negative gearing and CGT together. Those in the least need of financial assistance in the highest income bracket receive two-thirds of the twin benefits of negative gearing and CGT. As a form of redistribution of wealth, these are clearly regressive tax concessions. The tax schemes not only fail in their stated goals of increasing housing supply, but also adds to the bank balances of Australians with little need of assistance.

Positive Effects of Negative Gearing

These tax concessions may also have a destabilizing effect on the housing market and its investors’ finances. A housing tax regimen geared towards investment “encourages people to borrow more than they would otherwise to speculate on property values” (Davidson and Evans). With some economists claiming Australia’s housing market is on the verge of a bubble, these concessions encourage risky investment (Fernyhough). The UBS Global Real Estate Bubble Index currently ranks Sydney as having the world’s fifth worst housing bubble risk (UBS). As 90% of investment is in existing housing, the use of capital is entirely unproductive from the viewpoint of the economy. More investment should be directed to areas such as manufacturing and technology, which adds jobs and contributes to Australia’s economic growth.

Policy Inertia

Politically, there is little appetite within the current government for reform. People who own a home still far outnumber those who do not, and therefore form a potential voting bloc uninterested in rolling back tax concessions to their benefit. Hazel Blunden points out a kind of ‘political inertia’ around housing concession reform, with governments repeatedly leaving reform for an indeterminate future (Blunden).

Housing policy in Australia has been shaped by the mythology referred to earlier: owning a (preferably detached) home is a sign of financial maturity, and a necessary step towards becoming a full-fledged Australian. Jane-Frances Kelly and Paul Donegan, in their book City Limits: Why Australia’s cities are broken and how we can fix them, explored this unquestioning orthodoxy: “’Everyone wants to live in a ‘big house on a quarter-acre block’ – these words are said so often in Australia that they have passed into legend” (Kelly and Donegan). As more Australians are unable to afford a home, they are renting into their 40’s and 50’s, even into retirement, out of necessity. “Home ownership rates have also been declining among middle-aged households. This suggests most younger households aren’t ‘catching up’ later in life” (Kelly and Donegan). Another interesting statistic emphasises the instability renting in an investor’s market, “[t]he gap between owners’ and renters’ frequency of moving home in Australia is the widest in the developed world” (Kelly and Donegan). The point is that while these policies have increased the number of properties available to rent, they have reduced the number of owner-occupied properties. Together with the general lack of rights available to tenants in Australia (although some states offer more tenant protections than others), the policies have resulted in an unfair two-track system, improving the position of those able to buy into the myth of owner-occupation while preventing those who rent from buying into the myth.

Home-Owners vs Renters

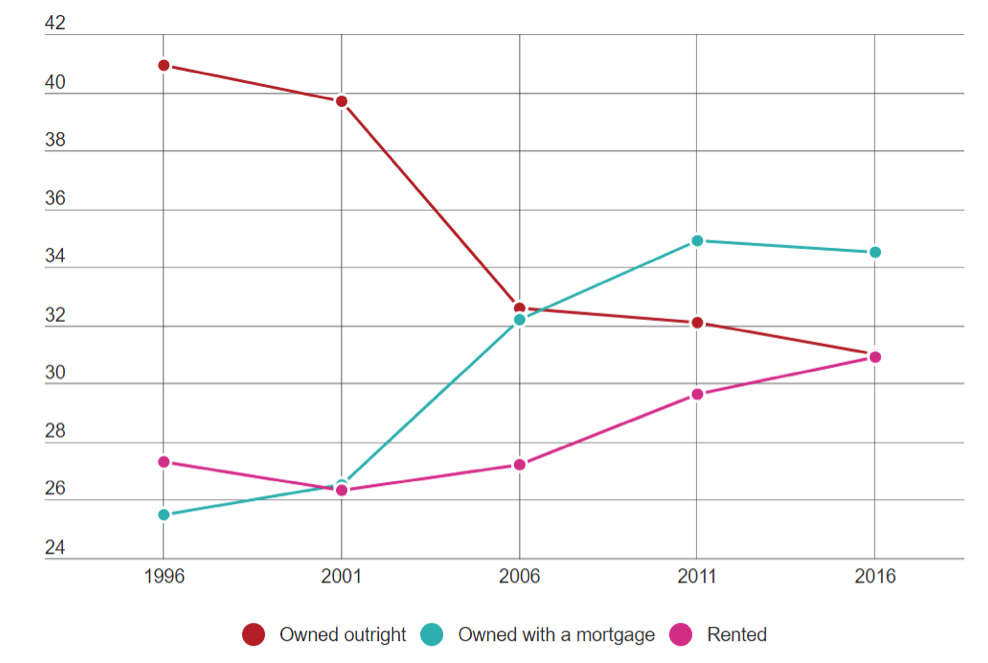

The long-term data on the rate of home ownership in Australia points to this same conclusion. The percentage of Australians who own their homes outright has dropped by 10% in the last 20 years (from 40% to 30%), and the numbers of renters has increased to the point where it drew even with home-owners in 2016 and was projected to increase from there (ABS Census). Those who have remained home-owners over this period have seen property values increase precipitously, and generous tax policies such as the CGT discount introduced. At the same time, mortgages offered by banks and credit unions have increased, indicating there remains a strong desire to either enter the property market or expand a property portfolio. The graph below illustrates these arguments.

Source: ABS Census

Given the distorting effects of increased property investment on the housing and rental markets, residential property should not be considered as simply another form of investment. Unlike the stock market, property is a tangible product and a prerequisite for people to enjoy a good standard of living.

Opposition Policy and History

There are various proposals for housing policy reform. For instance, the federal Labor opposition has reform to negative gearing as part of its policy platform. While admirable, the policy advocates for ‘grandfathering’ existing arrangements for those already benefitting from negative gearing, and restricting its use going forward. This carve out may be a required political compromise, attracting young voters while retaining the sizeable minority already investing in residential property. Unfortunately, it raises additional concerns about inter-generational equity: it would be reasonable to view an arbitrary cut-off date for new applicants (generally the younger generation) as lacking in fairness to those who never received its assistance. Perhaps the funds saved could then be funnelled into aiding first-home buyers.

The Labor government during the 1980’s attempted negative gearing reform, which lasted only two years. Opponents of reform point to the collapse of house prices and higher rents during that period as a portent of what will happen again with similar reform. However, other factors are marginalised in this narrative: the reforms coincided with a stock-market boom, which encouraged investors out of property and into shares. Pressure from the real estate lobby led to the scrapping of this reform. There are elements of this history useful for going forward. For example, the tax deduction allowed by negative gearing should be applicable only to the income generated from that investment, rather than against general income (such as salary) as it currently stands. This would lower the total deductions made (and therefore increase government revenue) while still allowing investors to recoup the costs of the investment should the income from that investment fall.

Conclusion

In the current housing climate in Australia, negative gearing and the capital gains discounts inflate house prices and subsidise high income earners. From an ethical standpoint, such a policy is clearly problematic. It is standard practice in most democratic societies to have taxes organised progressively, with the redistribution that occurs favoring people with lower incomes. Current housing policy in Australia instead rewards those with multiple properties, who have little need for financial assistance. Instead, government should focus on incentives to build new housing stock, increase public housing, and provide financial assistance for first-home buyers. Not only would this be fairer, but it would also increase the stability of the housing market. Hazel Blunden remarks that “the negative gearing debate in Australia crystallises broader debates about inequality, intergenerational conflict and the growing unaffordability of housing in Australia’s major cities” (Blunden). While critical of Labor’s proposal to grandfather negative gearing, these tentative steps at reform are at least a positive start.

Editor: Eric Witmer

References

Blunden, Hazel. “Discourses Around Negative Gearing Of Investment Properties In Australia.” Housing Studies, vol 31, no. 3, 2015, pp. 340-357. Informa UK Limited, doi:10.1080/02673037.2015.1080820.

Cho, Yunho et al. Negative Gearing Tax And Welfare: A Quantitative Study For The Australian Housing Market. University Of Melbourne, 2018, https://www.rse.anu.edu.au/media/2189538/Shuyun-May-Li-Paper-2017.pdf.

Davidson, Peter, and Ro Evans. Fuel On The Fire: Negative Gearing, Capital Gains Tax And Housing Affordability. ACOSS, 2015, http://www.acoss.org.au/images/uploads/Fuel_on_the_fire.pdf.

Fernyhough, James. “Housing Crisis Deepens As Australian Market Rated ‘Severely Unaffordable’ | The New Daily.” The New Daily, 2018, https://thenewdaily.com.au/money/property/2018/01/23/aus-housing-market-unaffordable/.

Grudnoff, Matt. Top Gears: How Negative Gearing And The Capital Gains Tax Discount Benefit The Top 10 Per Cent And Drive Up House Prices. The Australia Institute, 2015, http://www.tai.org.au/sites/defualt/files/Top%20Gears%20-%20How%20Negative%20Gearing%20and%20CGT%20benefits%20top%2010%20per%20cent.pdf.

Hanegbi, Rami. “Negative Gearing: Future Directions.” Deakin Law Review, vol 7, no. 2, 2002, http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/DeakinLRev/2002/17.html.

Kelly, Jane-Frances, and Paul Donegan. City Limits: Why Australia’s Cities Are Broken And How We Can Fix Them. Melbourne, Melbourne Univ. Publishing, 2015.

The Right To Adequate Housing. Geneva, United Nations, 2009, http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/FS21_rev_1_Housing_en.pdf.

UBS Global Real Estate Bubble Index, https://www.ubs.com/global/en/wealth-management/chief-investment-office/key-topics/2017/global-real-estate-bubble-index-2017.html

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) Census, 2016, http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/D3310114.nsf/home/census