Ethics Analysis: The (Non)Use of University Endowments for Pandemic Shortfalls

University endowments need to rediscover their true purpose

By Atrey Bhargava

A majority of US universities and colleges say they will not use money or returns from university endowments to meet pandemic shortfalls resulting from lower revenues. The decline in revenues is due to lockdowns and online teaching arising from the pandemic. The following analysis provides more details and clarity about the circumstances of these decisions and discusses whether it is fair for universities not to use their endowments, which can be sizable, instead of furloughing staff and cutting salaries and programs. (Hess, “At least 50,904 college workers have been laid off or furloughed because of Covid-19”). The analysis concludes it is not ethical for universities to lay off people and cut salaries rather than use endowment funds to fill budget gaps because of 1) the tiny gains from cost-cutting measures when compared to the total size of endowments, 2) the long-term cost of stopping activities that benefit the community surrounding the college, 3) the change in the purpose of endowments and the subsequent financial risk posed by them as witnessed during the 2008 financial crisis, 4) the conflict of interest between university governing boards and investment committees compounded with the excessive compensation awarded to fund administrators, and 5) the institutional difference between the purpose of businesses and educational providers.

1. Coronavirus, Endowments and the Financial Crisis

To evaluate the short and medium-run growth of endowments and investment income, the analysis of relevant data gives a better insight about the magnitude of financial problems caused by the coronavirus and the growth patterns of endowment value in the recent decades. The following tables represent specific dynamics of endowment growth patterns over the previous years.[1] The data are from a sample size of seven universities – Harvard College, Yale University, Stanford University, the University of Texas at Austin (large-size endowments), Tufts University, Swarthmore College (medium-size endowments), and Dickinson College (small endowment).

| College | AvgGrowth (2007-09) | Endowment 2019 (in billions) | AvgGrowth (2010-2019) | Projected 2029 (in billions) |

| Harvard College | -25.5% | 40.9 | 48.19% | 60.6 |

| Yale University | -27.56% | 30.3 | 81.44% | 65.5% |

| Stanford University | -26.74% | 21.9 | 57.55% | 53.5 |

| UT Austin | -37.38% | 35.5 | 112.57% | 80.8 |

| Tufts University | -26.67% | 1.98 | 65% | 42.1 |

| Swarthmore College | -20% | 2.13 | 42% | 41.7 |

| Dickinson College | -15.15% | 0.45 | 45.16% | 41.1 |

Endowment Statistics 1

| College | Operating Costs 2019 (in billions) | Endowment Contribution (in billions) | %total endowment | %operating costs |

| Harvard College | 5.5 | 1.7 | 4.16% | 35% |

| Yale University | 5.0 | 1.4 | 4.62% | 34% |

| Stanford University | 5.9 | 1.3 | 5.94% | 22% |

| UT Austin | 4.5 | NA | NA | NA |

| Tufts University | 0.94 | 0.07 | 3.54% | NA |

| Swarthmore College | 0.16 | 0.08 | 3.76% | 48% |

| Dickinson College | NA | 0.01 | 2.22% | NA |

Endowment Statistics 2

Astute observations from the data inform us about the growth dynamics of endowments:

- Because of the financial crisis of 2008 and the exposure of these endowments to high-risk alternative investment vehicles (private equity, venture capital, hedge funds and the like), average college endowment (unweighted) decreased by 25.57% for the given sample between 2007-09.

- Despite this decrease during the financial crisis, the average growth in endowments between the period 2010-19 was 64.56%.

- The projected 2029 endowment value for the seven colleges is not a sophisticated forecast, but serves to illustrate what can happen to college endowments if they grow at the same rate as 2010-19.

- Endowment Contributions refer to income from the endowments used towards the operating costs of the college in a given year.

- % total endowment refers to the percentage of endowment income used in a given year against the total endowment of the college.

- % operating costs refer to the contribution of endowments towards the operating costs of a college in a given year.

Key insights from the observations are: 1) If college endowments continue to grow at the same rate as the previous decade, using the endowment to cover costs resulting from the coronavirus should not be much of a debate. This point is driven home in the next part of the analysis that evaluates the income saved from cost-cutting measures because of the coronavirus; 2) If college endowments are to grow at a different, perhaps slower pace than the previous decade, the costs resulting from the coronavirus are still incomparable to the endowment losses during the 2008 financial crisis. If colleges can so handsomely come back from the crisis (average growth 2010-19), and % total endowment remains below 5% even in 2019, it is not unreasonable to expect that the budgetary shortfalls because of the coronavirus can be covered by endowment income instead of other cost-cutting measures universities are currently undertaking. This inference is much more accurate for colleges with large and mid-size endowments, which represent 6 out of the 7 colleges in our sample.

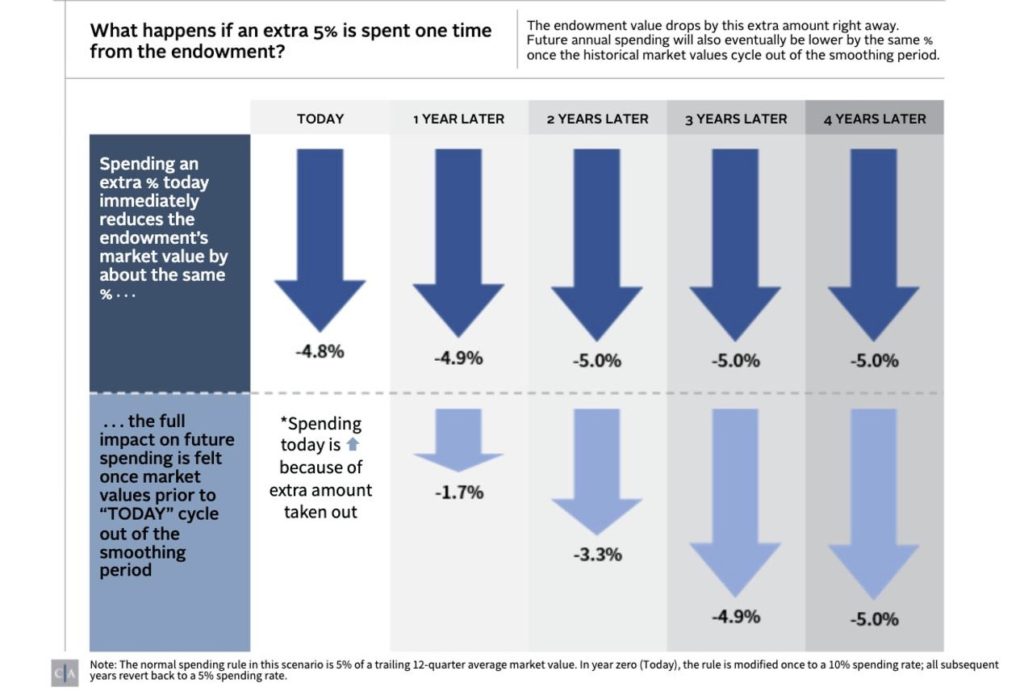

Notwithstanding, there can be a small short-term cost if endowments do not stick to their current model of contributing only a certain (limited) amount of income from their portfolios towards the operating costs of a university in a given year. Using more endowment income than required in a given year will reduce the principle value of endowments and the subsequent investment proceeds accruing to it over a short-run period. [2] The following chart by Cambridge Associates estimates that if an extra 5% of the endowment is used to cover operating income shortfalls because of the coronavirus, not only will the principal value decrease by 5% instantaneously, but also the investment income accrued from endowments will continue to reduce over a five-year period (impact on future spending).

This short-term cost is, however, mispresented in the figure above, broadcast by Cambridge Associates in their webinar on understanding the use of endowments to rescue colleges from the financial difficulties accruing because of the coronavirus. Not only is the above figure not illustrative of the returns from investment income accruing from the growth of endowments (average growth 2010-19), but it also disregards the multiplicative cost of stopping community activities and furloughing administration, faculty and other employees of the university. The limited negative short-run impact on endowment contributions (which can very well change with university policy as shown by the statistic % endowment that reflects how miniscule university endowment contribution per year is in comparison to total endowment value) is not only questionable considering previous growth but also incomparable to other real costs of the cost-cutting measures employed by universities.

Moreover, the volatility of financial markets, as seen by events such as the financial crisis and the coronavirus where college endowment values for the sample decreased by an average of 25.57%, shows why increasing endowment pay outs per year might be a viable policy change considering the excessive volatility in endowment value because of financial turmoil. Volatility increased first with the 2008 financial crisis, and now with the coronavirus. The excessive volatility because of high-risks in the market should incentivize colleges to increase the income used from endowments towards operating costs in a given year. For example, while Harvard College lost nearly 25% of its endowment value (approximately 9 billion dollars) because of the financial crisis in one year, it only uses an approximate 4% of its endowment for operating expenses in a given year. If Harvard can handsomely recover and nearly double its endowment value in ten years, it is reasonable to assume it can also recover the endowment funds used to mitigate cost-cutting measures.

To provide some empirical grounding to this argument, simply estimate the monetary income saved because of cost-cutting measures employed by universities to meet budget shortfalls resulting from the coronavirus. As it is difficult to find one number to estimate the budget shortfalls resulting from the coronavirus – due to lower enrollment, loss of revenues in residential and dining halls, library services etc., this analysis uses statements from university presidents’, as well as the estimated impact of similar pronouncements during the financial crisis to understand the cost saved in furloughing staff and stopping community-oriented activities.

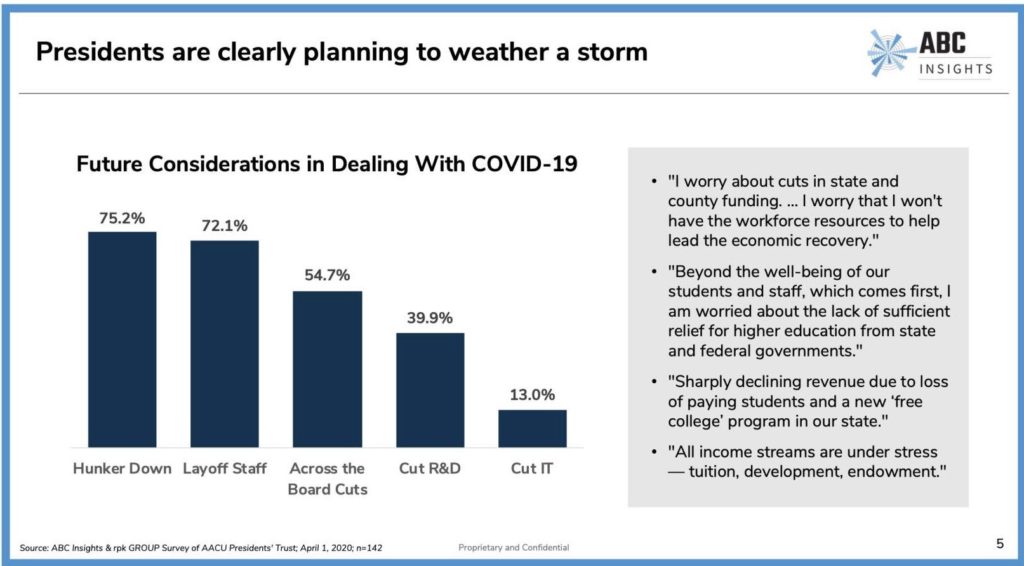

In the words of Stanford University President Marc Tessier-Lavigne, these actions include “a salary freeze, a hiring pause, a pay reduction for senior leadership, reduction of discretionary spending by departments, and a hold on approvals of all new capital projects.”(Tessier-Lavigne, Message from Stanford University President) These reforms, however, are in no way exhaustive and only showcase the cost-cutting measures employed by a University with one of the largest endowments in the world. Similarly, UT Austin – the University with the second-biggest endowment after Harvard in 2019 – is considering “mitigation plans (that) will likely include furloughs or permanent reductions in force for staff members in … units where revenues have declined.”(Andu,“Budget cuts at UT-Austin will likely bring furloughs and layoffs”) While these two universities are in our sample size, a report by ABC Insights covering 142 institutions (including four year private and public universities as well as two year community colleges) gives a better picture of the general feeling of college presidents with regard to future considerations in dealing with Covid-19.[3]

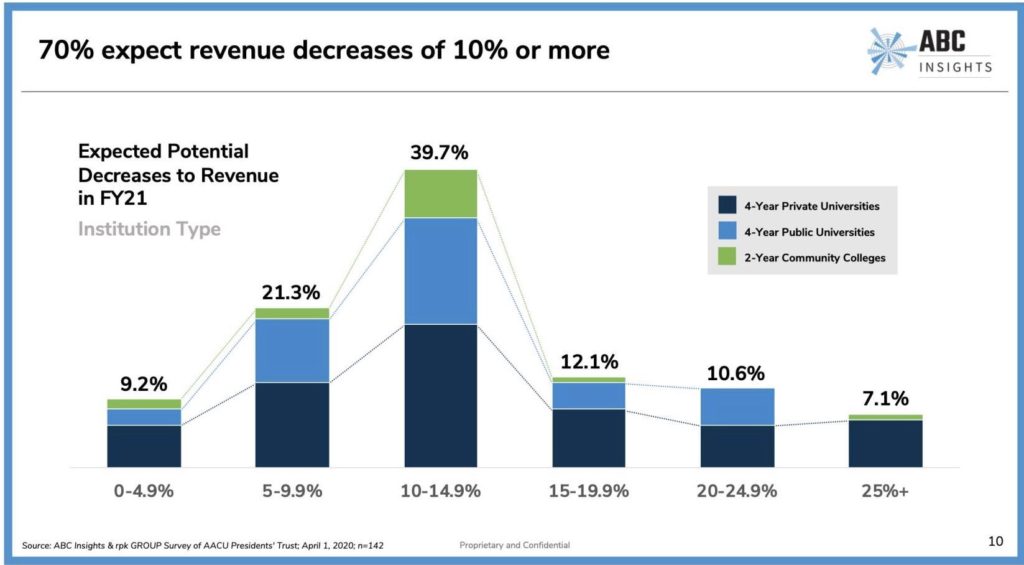

Moreover, the same report finds that 70% of University Presidents expect revenue decreases of 10% or more.[4]

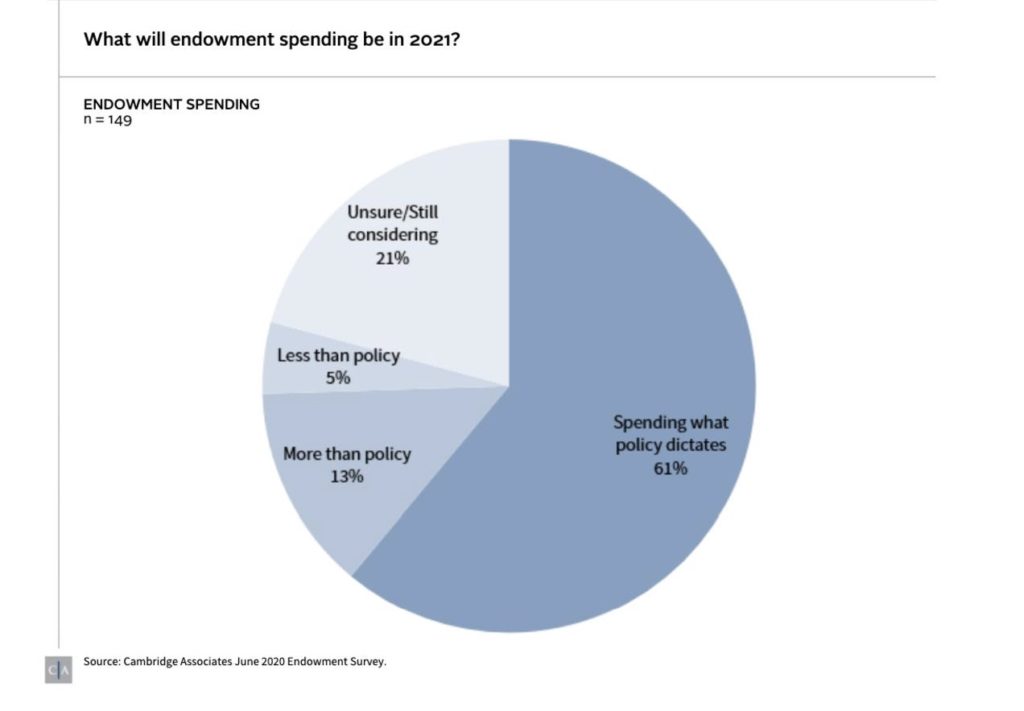

Considering that the annual revenue for Harvard in 2018 was $5.2 billion (even if we do not account for the operating surplus of $196 million for the same year), 10% of $5.2 billion is $520 million dollars. This amount is equivalent to an approximate 33% increase in the endowment contribution towards operating expenses of fiscal year 2019. If we put it into perspective, $520 million only accounts for 1.2% of Harvard’s total endowment value of $40.9 billion. Considering the losses of nearly $9 billion during the financial crisis, the budget shortfalls resulting from the coronavirus are miniscule. Yet, in a poll carried out by Cambridge Associates to estimate whether universities are looking to use endowment income, the following are the results.[5]

Another dimension that further aggravates cost-cutting measures employed by universities is the multiplicative impact these cuts have in the medium run on surrounding communities in which they are located. A report by the Tellus Institute tracks the negative impact of the cost-cutting measures employed by universities in the wake of the financial crisis. To get a sense of the overall economic impact from reductions in force, Tellus uses the regional input-output modelling system (RIMS II) developed by the U.S. Commerce Department’s Bureau of Economic Affairs for the educational services sector in the Boston-Cambridge-Quincy area. For the 778 workers in the Boston region, Tellus estimates a direct earnings loss of more than $46 million per year and $135 million when using the RIMS II multipliers. Moreover, for the six schools in the study – Harvard, MIT, Boston University, Dartmouth University, Brandeis and Boston College – Tellus predicts, at the very minimum, more than $160 million lost in annual economic activity in the community in which the schools are located, solely due to job losses. (Tellus Institute)

Stoppage of construction activity, much like the reality of Harvard’s Allston initiative that was stopped in its tracks after the financial crisis of 2008, can have adverse effects on those communities promised investment. In the case of Allston this was particularly worrisome. Not only did Harvard crowd out local businesses to buy residential land, but after the financial crisis, it was unable to carry on the scale of the projects it had earlier planned in the neighborhood, further negatively impacting the economic opportunities available to people in that community. To estimate the broader economic impact of Harvard’s halting of construction in Allston, the Tellus Report uses RIMS II and applies its demand multipliers for the Boston region to Harvard’s job-creation estimates. It estimates that a “one-year delay in moving forward with the initial Phase 1A projects would result in lost direct earnings of more than $85 million and a total economic impact for the region of approximately $275 million. A two-year delay would result in lost short-term earnings estimated at more than $170 million, and a total economic impact of approximately $550 million. With a three-year delay, the figures increase to more than $270 million in lost earnings and a total regional economic impact of more than $860 million over the first three years. These impacts are driven solely by the forgone earnings of construction workers and permanent employees; they do not include the impacts of the lost procurement spending for construction materials and equipment that would have occurred in the region.” (Tellus Institute)

The construction halt of the Allston project was only lifted in 2014 (Staff Writers, Harvard Crimson), after negatively affecting the growth of that community by approximately $1 billion dollars according to RIMS II multipliers. The hardship caused by cost-cutting measures after the financial crisis led to lasting job losses, stalled construction projects, and local business downturns in college communities that used to be secure havens of regional employment and economic resilience. With the coronavirus, this time will be no different if universities institute similar cost-cutting measures. Considering the insignificance of the operating income lost compared to the overall endowment size of many of these colleges, it is severely problematic if hedge fund and private equity managers hired to manage college endowment funds are not the ones who suffer but instead, faculty and staff must sacrifice again.

2. Endowments and Financial Risk

The purpose of endowments before the 1970s was to ‘secure’ money. ..today the purpose of endowments is to ‘make’ money.

The report by the Tellus Institute highlights the historical evolution of the structure of endowments. Endowments today are generally made of illiquid, riskier asset classes: Private Equity, Venture Capital, Hedge Funds, and real assets such as oil & gas and commodities such as private real estate and timberland. This portfolio mix has historically not been the case. The purpose of endowments before the 1970s was to ‘secure’ money. Over time the purpose has morphed and today the purpose of endowments is to ‘make’ money. Before the 1970s, endowments primarily invested in public equities and money market instruments and while they had admirable returns, it was nowhere in comparison to the kind of growth seen in the immediate decade before and after the financial crisis. In fact, since the 1970s, finance has superseded fundraising as the main vehicle for the growth of endowments.

This culture of high-risk endowment investing started with professors and investment professionals from Dartmouth and Yale. Any college with a respectable endowment size has now adopted their model. The goal of this model of endowment growth focuses on maximizing long-term total return – not only with the actual yield generated from interest and dividends but also the unrealized capital gains from any appreciation in the principal value of securities held in the endowment. The model also de-emphasizes liquidity and leaves little to internal management. (Taylor, “Universities Are Becoming Billion-Dollar Hedge Funds with Schools Attached”) It ensures most of the investments are managed by external managers who have market experience in generating profits and revenue. The Yale model borrows from Modern Portfolio Theory that proposes risk and return are highly correlated and diversification of asset classes is the means to mitigating substantive risk. Incidents such as the tech bubble of the early 2000s and the subsequent fall in public equity companies paved the way for more medium-sized endowment colleges to invest in alternative investment vehicles similar to Yale’s and Dartmouth’s. (Tellus Institute)

The report by the Tellus Institute argues university endowments are not innocent victims but actually played an integral role in enabling the financial crisis of 2008. “By engaging in speculative trading tactics, using exotic derivatives, deploying leverage, and investing in opaque, illiquid, over-crowded asset classes such as commodities, hedge funds and private equity, endowments played a role in magnifying certain systemic risks in the capital markets. Illiquidity, in particular, forced endowments to sell what few liquid holdings they had into tumbling markets, magnifying volatile price declines even further. The widespread use of borrowed money amplified endowment losses just as it had magnified gains in the past.” Additionally, the endowment model of investing encourages imitation and capital crowding, and the involvement of ‘always’ credible influential investors such as Harvard lends credibility to any asset class, whether justified or not. (Tellus Institute) This capital crowding, both from endowment money and the $23 trillion worldwide pension plan assets market, was one of the main reasons for the overcapitalization of the shadow banking sector that directly contributed to the financial crisis of 2008. (Metrick & Gorton, “Guide to Financial Crisis”) All this evidence serves to illustrate the enormous risk endowments create in the financial sector because of their current modality.

Conflicts of Interest

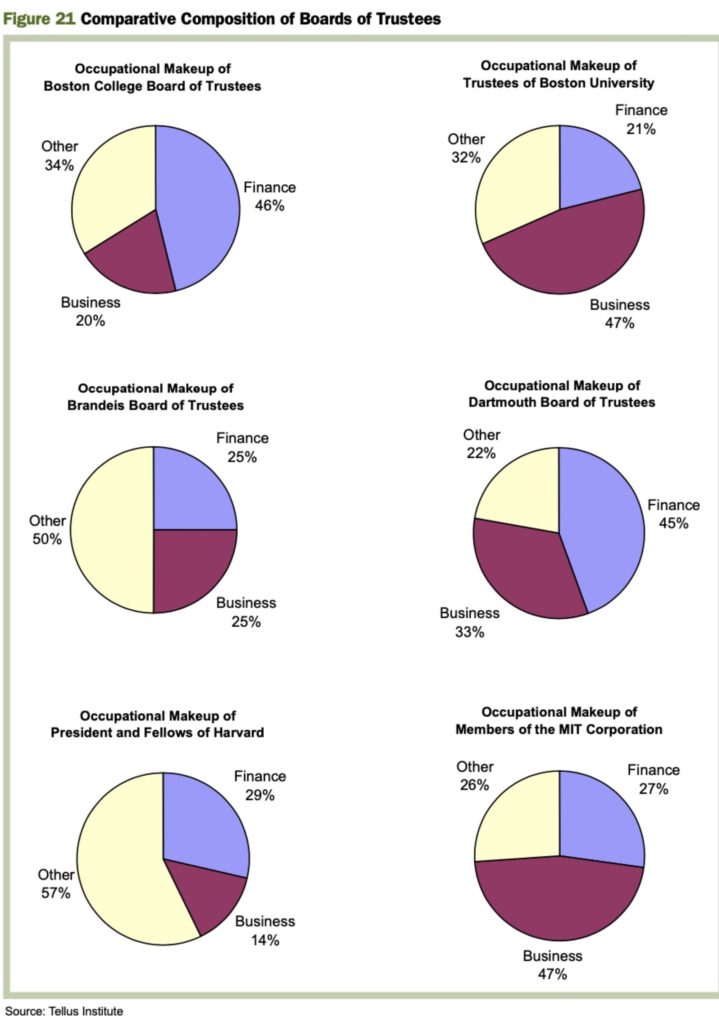

The last part of this section presents the composition of the boards of universities, the conflicts of interest among their members and the excessive compensation to finance officers as indicators of the increasing culture of risk that allowed the endowment model to erode. With the departure of Chief Investment Officer (CIO) David Russin from Dartmouth in 2009, for example, investment committee chair and trustee Stephen Mandel played the role of the CIO until he became chair of the board of trustees later that year. In this time, Mandel’s firm, Lone Pine Capital LLC managed an investment mandate of $10 million from the college endowment. The college has a conflict of interest policy, yet the investment committee depends heavily on its chair and it is questionable whether there can be proper oversight of investments which are managed by a trustee serving as a de-facto CIO. Mandel, however, is only one of the more than half a dozen Dartmouth trustees whose firms manage millions of dollars for the Dartmouth endowment. 70% of Dartmouth’s trustees hold MBA’s, and 45% worked in finance as of 2010. Similar statistics are true for all the colleges mentioned in the Tellus study. [6]

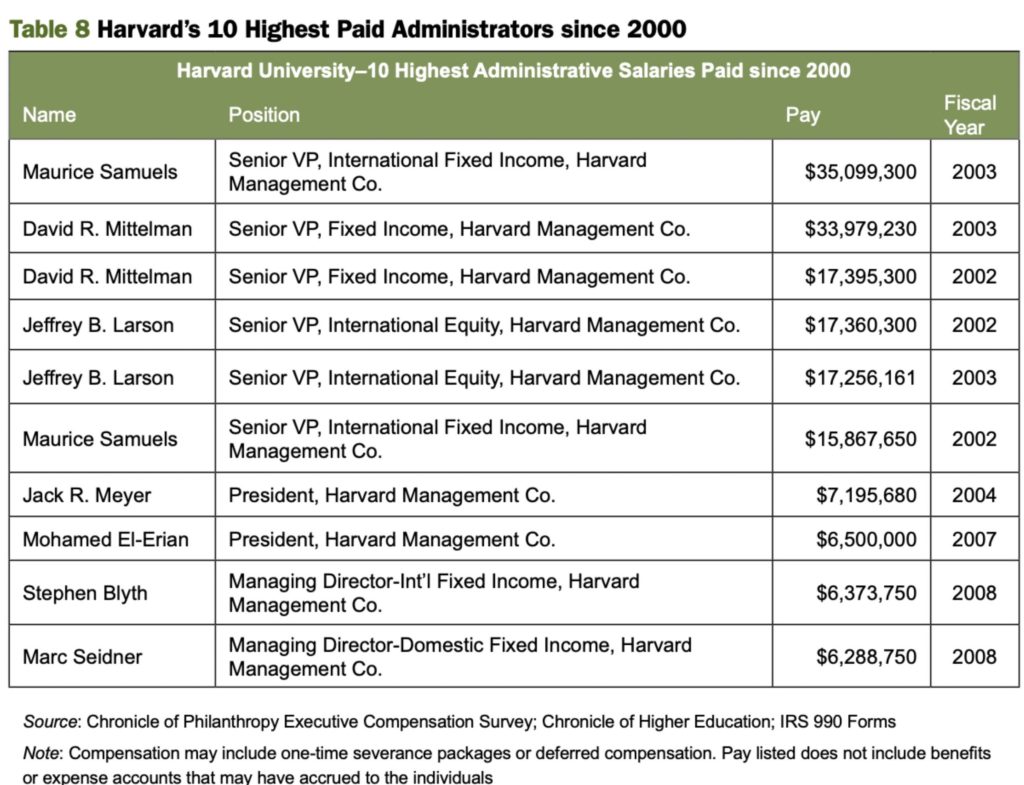

The conflict of interest between governing boards and investment committees seems common practice. In addition, there apparently is a culture of excessive compensation for finance officers and external managers of endowment funds. The following table shows the statistics for the 10 highest paid administrators at Harvard. This theme persists across the colleges analyzed in this study. [7]

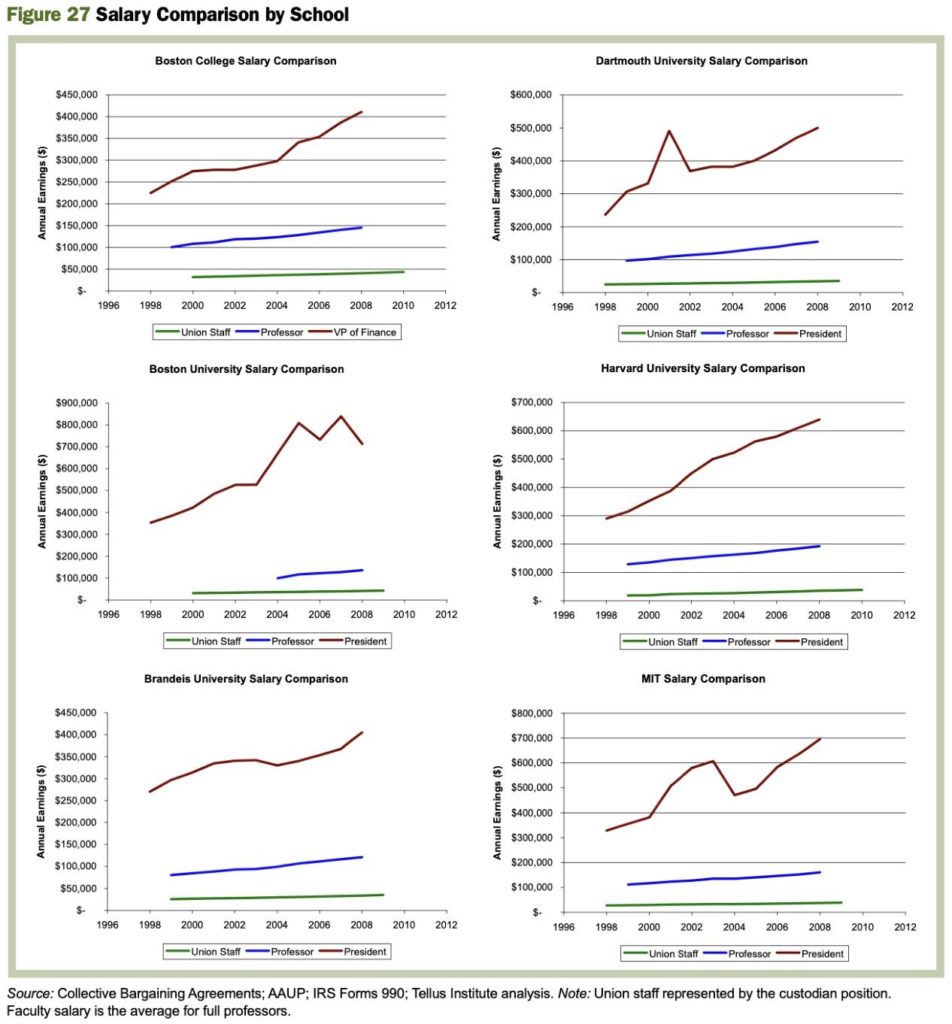

Excessive compensation has widened the pay-gap between over-compensated senior endowment administrators and modestly compensated staff further exacerbating income inequality not only within the college, but also around the surrounding communities.[8]

This culture of excessive compensation has increasingly intertwined the worlds of finance and higher education. In consequence, the linkage normalizes high-risk, illiquid investments in alternative assets by educational institutions.

Tying back to the original question regarding whether endowment money should be used instead of cost-cutting measures instituted during the pandemic, the argument is, because endowments contribute to financial risk (the financial reports have not changed much between 2007-19 except for a certain percentage allocated towards liquid cash [Harvard Management Company, Letters from CEO 2010-19]), it is reasonable to use endowment income instead of stopping community-oriented activities. The reasons are twofold. First, there is an inherent risk of portfolio volatility because of the current nature of endowment investing. Losses accruing from using endowment money in the short run have little negative implications in the long run. Second, there is a more fundamental risk to the financial ecosystem because of the endowment investing model. Using more endowment income in the short run consequently decreases the overall value of endowments and may reduce overall risk in the financial ecosystem.

There is a reason for a lack of consensus on this debate. The excessive salaries of “financiers” in the college act as a direct incentive for them to capture as much endowment money as they can. Add to that perverse incentive, the conflicts of interest between university governing boards, trustees, and internal and external investment offices, we better understand one likely reason why universities choose not to use endowment money to tackle the coronavirus induced budget shortfall.

3. Colleges, Government, and Responsibility

This analysis criticizes both the structure of endowments that contributes to financial risk in the economic ecosystem, and also the decision by colleges to not use their endowment income to cover revenue shortfalls ensuing from the coronavirus. The Endowment Model of Investing, however, is not uncommon among institutional investors. Educational institutions are different from profit seeking corporations. This difference is primarily attributable to their status as non-profit organizations (as recognized by the US government). The vast majority of public universities are tax-exempt entities as defined by the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) Section 501(c)(3). This status allows them a myriad of unique opportunities, some of which are:

- Most of the school’s own tax-exempt real estate. For the six schools in the Tellus study, this tax-exempt real estate was worth more than $10.6 billion. In 2009, these schools ended up paying less than 5% of the $235 million in taxes they owed to the government. This implies that local communities bear a cost – forgoing property taxes – when they allow colleges to be in their neighborhood. (Taxation Report, “Present Law and Background Relating to Tax Exemptions and Incentives for Higher Education”)

- Gifts to the endowment are tax-deductible to donors, and investment gains and income that endowments generate are tax-exempt. These exemptions allow investment managers to rapidly trade without considering the tax implications of their investment decisions.

- Tax-exempt bonds allow colleges to borrow at low-interest rates while maintaining their investments in often high-risk, high-return assets. This allows colleges to engage in indirect tax arbitrage. Colleges use tax-exempt bond proceeds for operating expenses while placing their endowments in illiquid alternative investments to chase higher rates of return. Considering the illiquidity in alternative investment vehicles, colleges have often turned to bond markets for cash. Robert L. Culver, head of Mass Development – one of the two main agencies in the commonwealth of Massachusetts’ issuing bonds to educational institutions – has argued “that the greatest contributor to the enormous growth in University endowments and other endowments is not some wealthy person or persons, but the federal government making available low-cost, tax-exempt debt that allowed endowments to remain invested and earn rates in the market as high as 25 percent.” (Tellus Institute)

Universities, unlike businesses, are not subject to tax on investment income, payout requirements and qualify as a tax-exempt charitable organization because they “foster the productive and civic capacities of citizens.” (IRC Code Section) Universities need to be cognizant of this difference and allow for policies that respect these values. One of these would be to use endowment income instead of furloughing staff or stopping construction activity because of the coronavirus.

4. Ethics Analysis

The budget shortfalls because of the coronavirus are incomparably smaller than the endowment losses of 2007-09. It is therefore, not fair for colleges and universities with medium and large-sized endowments to layoff/furlough workers or stop capital projects that would have contributed to their surrounding communities. A simple utilitarian calculation supports this conclusion.

University administrators have fallen prey to the ideology of neo-liberal economics, even as they serve in a non-profit, educational environment.

Universities argue that taking more money out of the endowment can have a deleterious impact on revenue for future generations. Yet, the average growth and gains of endowments in the decades before and after the financial crisis refute this argument. Universities have lost sight of the purpose of their endowments which is to help the stakeholders of the universities. The endowments are meant to cushion hard times. Instead of helping stakeholders, the purpose of endowments has now morphed to profit maximization, at whatever cost. In other words, university administrators have fallen prey to the ideology of neo-liberal economics, even as they serve in a non-profit, educational environment.

The financial crisis and the coronavirus reiterate the volatility of profits and gains and rationalize why it is fiscally sensible to increase endowment contribution in the short run, at the minimum. For the two colleges in our initial sample size of seven, both Stanford University and the University of Texas at Austin have decided to furlough workers and hold the investment approval on new capital projects. Such actions have a severely negative impact on the income of not only the staff but also of the surrounding community. This is numerically a much larger number of people than those who gain from endowment income in the short run i.e. asset managers. Thus, from a utilitarian perspective, not using endowment funds to counter staff cuts and salary reductions during a coronavirus caused budget crisis, is unethical.

Conclusion

It is not fair for universities to furlough workers or stop capital projects because of the coronavirus. Support for this conclusion comes from presenting a) the dynamics of the growth of endowment patterns in recent decades, b) the insignificant dip in endowment value if used for revenue shortfalls (from the coronavirus) when compared to the financial crisis, c) the financial risk endowments create in the economic ecosystem, and d) the institutional difference between the characteristics of universities and businesses. The conflict of interest among trustees, governing boards, University endowment offices, and professional investment management services, gives reason to suspect why colleges are not using additional income from their endowments in the short run. Instead, coupled with furloughing workers and stopping capital projects, they are planning to access government bonds and increase fundraising efforts to mitigate the revenue loss. As shown in this analysis, using endowment income is a simple remedy to address the budget shortfalls resulting from lower revenue and there is little economic or ethical justification for taking any other course.

Works Cited

ABC Insights, Colleges and Coronavirus, June 15th, 2020.

Abigail Hess, “At least 50,904 college workers have been laid off or furloughed because of Covid-19”, July 2, 2020, CNBC.

Amy Whyte, “Here’s what determines how much endowment CIO’s get paid”, January 3rd 2020, Institutional Investor, Here.

Andu Naomi, “Budget cuts at UT-Austin will likely bring furloughs and layoffs, campus leaders say”, May 19th, 2020, The Texas Tribune.

Astra Taylor, “Universities Are Becoming Billion-Dollar Hedge Funds with Schools Attached”, The Nation, March 8th, 2016.

Bloomberg, “Harvard Leads in endowment manager pay”, July 18th, 2014. Here.

Ben Unglesbee, “How the wealthiest colleges manage their endowments in a financial crisis”, March 19th, 2019, please see here.

BU Today, “Facing $96M Shortfall, President Brown Announces Layoffs, Furloughs”, June 29th, 2020. Please see here.

College Endowment Database, 2013-17, U.S Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, for more please see here.

Chronicle Staff, “As Covid-19 Pummels Budgets, Colleges Are Resorting to Layoffs and Furloughs. Here’s the Latest”, July 2, 2020, here.

Elyssa Cherney, “Northwestern University furloughs staff, cuts executive pays and taps endowment as its eyes ‘significant shortfall’ due to coronavirus pandemic”, May 11th, 2020.

Gorton & Metrick, “Getting up to speed on the financial crisis: A one weekend reader’s guide.”, JEL 2012.

Goldie Blumenstyk, “Average Return on Endowment Investment is worst in almost 40 years”, January 28th, 2010, see here.

Harvard Management Company, Letter from the CEO, 2010-19.

Joint Committee on Taxation Report, JCX-62-12, “Present Law and Background Relating to Tax Exemptions and Incentives for Higher Education”, July 25th, 2012.

Marc Tessier-Lavigne, “a message from the president: our financial future”, Stanford University, May 27th2020, please see here.

Russ Shafter-Landau, “The Fundamentals of Ethics”, Fourth Edition, Oxford University Press, 92-106.

Staff Writers Harvard Crimson, “The Allston Science Complex’s Winding Path to Completion”, May 27th, 2020.

Tax Exemption for University and Colleges, Internal Revenue Code Section 501(c)(3) and section 115. Here

Tellus Institute Report, “Educational Endowments and the financial crisis: social costs and systemic risks in the shadow banking system: a study of Six New England Schools”, Principle Investigator and Lead Author: Joshua Humphreys.

Utilitarianism, Seven Pillars Institute.

Reports Database for Estimation on Growth Patterns in Tables 1 and 2:

Dickinson College Reports, here.

Harvard Management Company, Endowment Report, 2007-19, here.

Harvard Financial Report, 2019.

Scott Galloway, “This Chart Predicts Which Colleges Will Survive the Coronavirus

”, July 21st , here.

Stanford Management Company Reports, 2007-19, here.

Stanford Financial Report.

Swarthmore College Financial Reports, 2007-19, here.

Tufts University Financial Reports, 2007-19, here.

UTIMCO Annual Reports, here.

Yale Press Releases, Endowment Updates 2007-19, here.

Yale Financial Report 2019.

[1] Unfortunately, the data collected in these tables have deficiencies for school-specific data is non-standardized, inconsistent, incomplete, fragmentary and scattered across, municipal, state SEC, IRS filings, and incommensurable financial reports. The NA’s represent information that is not accurately available because of the lack of data.

[2] Cambridge Associates Webinar, “Endowment Spending to the Rescue”, latest insights July 2020, here. (Figure 1)

[3] ABC Insights, Colleges and Coronavirus, June 15th, 2020. Also see, BU Today, “facing $96M Shortfall, President Brown Announces Layoffs, Furloughs”, June 29th, 2020. please see here. (Figure 2)

[4] ABC Insights, Colleges and Coronavirus, June 15th, 2020. Also see, BU Today, “facing $96M Shortfall, President Brown Announces Layoffs, Furloughs”, June 29th, 2020. please see here. (Figure 3)

[5] Cambridge Associates Webinar, “Endowment Spending to the Rescue”, latest insights July 2020, here. (Figure 4)

[6] Tellus Institute Report, “Educational Endowments and the financial crisis: social costs and systemic risks in the shadow banking system: a study of Six New England Schools”, Principle Investigator and Lead Author: Joshua Humphreys. (Figure 5)

[7] Ibid, (Figure 6)

[8] Ibid, (Figure 7)