Community Banking: The Case of The Bank of Prairie Village

By: Nathaniel Crosser

People are disillusioned with and distrust bankers. Yet in many areas “banking” is not a dirty word and bankers are respected members of their communities, much like town doctors or lawyers. Such bankers operate community banks, entities unlike their bulge bracket megabank brethren we read about in the news. It is important to understand the differences between community banks and banking conglomerates such as Bank of America Merrill Lynch and JPMorgan Chase & Co.

The Case Study: The Bank of Prairie Village (BPV)

Prairie Village, Kansas is a small town of about 20,000 on the south side of the Kansas City. The bank is two stories of red brick in the heart of the financial district. The interior contains a cozy assortment of sprawling desks partitioned by glass walls. Originally chartered in 1931 in Hartford, Kansas, the bank has been based in Prairie Village since 2003. The bank has a five star safety rating from Bauer Financial and was rated by Money Magazine as one of the few banks in the nation above $100 million in assets with a perfect “Texas” ratio during the height of the financial crisis. The bank describes itself as a “purveyor of hometown, small batch banking”, appealing to images of a master distiller crafting a batch of fine bourbon. The Bank of Prairie Village serves as a model for community banks across the Midwest and America.

Dan Bolen (J.D., LL.M.), Chairman BPV

Dan Bolen is Chairman of the Bank of Prairie Village and author of Pinstripes, Wingtips, Cigars & Collateral: Business Lessons for the New Graduate. The author had a chance to sit down with Mr. Bolen and find out more about BPV and Community Banking.

Dan Bolen (second from right) with members of the community. (Courtesy of pvppost.com)

What is Community Banking?

Community banks are typically locally owned, independent, and operated by members of the community they serve. However, this definition does not place any restriction on size. Community banks can have anywhere from a few million to several billion dollars in assets. There are currently over 6,000 community banks operating over 52,000 offices and employing around 700,000 people in the United States. According to the FDIC, community banks hold just 14 percent of industry assets, but make up almost 95 percent of all U.S. banking organizations. Community banks hold the majority of deposits in micropolitan (urban core containing 10,000-50,000 people) and rural areas, but are dwarfed by large banks outside of those spheres. “It’s unique for a small bank in a metropolitan area, NFL size city, but if you get into smaller hometown banks you get a very similar feel to them. At least the ones that have survived,” states Bolen. These banks differ from megabanks by more than just location and ownership, however. Community banks are unique functionally, structurally, and ethically from large banks.

How Community and Large Banks Differ Functionally (for Clients)

For a client, a community bank ultimately serves the same function as any other bank: to secure and increase assets and provide access to capital. However, there are a few notable differences.

- There is a social aspect to community banking. Interactions are commonly conducted in person – a far cry from the impersonal drive-thru tellers and online banking portals (although many community banks do offer these services). “The banking representatives on the floor everyday know almost all the customers by name and know their families,” says one of the bank’s summer interns, Keaton Cross.

- Loan decisions are not based solely on credit scores. Loans can be more appropriately approved or denied given the character and unique circumstances of the potential debtor. This helps prevent bad loans while accommodating some who may be blighted by poor credit scores.

- Many community banks, such as BPV, do not generate fee incomes. That means they often do not charge their customers ATM fees, checking fees, and especially not the $35 overdraft fees that Bank of America They prefer to make money with their clients, not at their expense.

- Community banks provide simpler offerings. They do not generate Credit Default Swaps, Collateralized Debt Obligations, or other flashy securities concocted on Wall Street. For those who seek more exotic investment options, a community bank may not be the right place.

How Community and Large Banks Differ Structurally (for Employees)

Most obviously, community banks have relatively few employees. However that doesn’t mean they have to scrape by to make ends meet. This is especially true in the information age where computers can be a great equalizer. “Technology allowed us to increase productivity,” elaborates Bolen, “a generation before a bank this size would have eighty employees. We have fourteen. The profit number is the same.”

The branches and divisions of community banks typically take deposits and make loans within their physical area. When an individual deposits money with her community bank, that money will likely be reinvested locally and leave the community stronger. You will not find investment banking or global financial speculation at BPV – just commercial, local, client-driven banking activities.

Most notably, there are cultural distinctions between the megabanks and community banks. A community bank is not a faceless corporation. It is an institution rooted deeply in the community. The Board of Directors usually comprises of local business leaders, not the wealthiest men and women of America. “If it fails, it’s not a shareholder write-off. It’s a family. The family and the community. I’ve got to make my community survive,” remarks Bolen. The bank and the people of the community are engaged in a symbiotic relationship. In addition, the bank employees who reside in the community are more likely to be rooted at their respective bank, and not use their position as a stepping-stone to further their careers. Employee turnover at BPV, for example, is extremely low. In the past fifteen years, there has been one full-time employee leave for another commercial bank.

How Community and Large Banks Differ Ethically

Following the Financial Crisis of 2007-2008 many of the unethical business practices at some of the major banks have come to light (see our analysis of the BoA takeover of Merrill Lynch). “There is evidence of deep-seated cultural and ethical failures at many large financial institutions,” said William Dudley, the President of the New York Federal Reserve Bank in a speech in 2013. These ethical shortcomings have manifested themselves in several ways. Most notably are the excessive, inappropriately timed banker bonuses and an apparently intentional lack of transparency over the financial health of the banks. Emotionally detached from their customers and personally shielded by the name of their company, big bankers are not necessarily concerned about the fate of other people’s money.

Bolen argues the personal nature of community banks inherently makes them more ethically run: “It’s easier to be ethical when every day you’re tied to it. I have to look every one of them [clients] in the eye. They come in with their kids or grandmother. There is almost a built in check and balance.” Due to their symbiosis with the community in which they operate, community bankers are incentivized to make lending and investment decisions that are in line with the long-term best interests of the community and its members. If a community banker behaves unethically, he or she faces backlash from her friends and neighbors and suffers “reputational risk”.

The deposits of those who bank with community banks such as BPV have the full backing of the FDIC. “I don’t sell any kinds of deposits that aren’t federally insured. I can look everyone in the eye and know the money you’re giving me, I am giving you back,” says Bolen. It is a banking system founded on relationships and mutual trust, not a securities arms race.

With a flatter organizational structure, smaller bank bosses can cultivate and ensure the ethical behavior of all of their agents more effectively. If Wall Street bankers mine for gold on their computers they tend not to focus on either the public’s or the bank’s best interests. This agency dilemma is not as much of a problem when a strong ethical foundation is in place. “The way he [Bolen] acts trickles down to everyone. He taught me how to go above and beyond for the customer,” explains Cross.

The Status Quo

As we continue to recover from the Financial Crisis of 2007-2008, many are worried regulators proceeded only reactively. Many argue Dodd-Frank fails to remedy the root cause of the crisis – inefficient regulation of systematic risk. Many large banks still leverage gratuitous debt-to-asset ratios and peddle insidiously risky securities with relative impunity. Under Dodd-Frank the largest banks (SIFIs) will still receive bailout money from the FDIC should one of these “systematically important financial institutions” fail. Now, however, when such a bailout occurs, the government will recoup its costs by collecting fees from the other SIFIs. This leads to a sort of prisoner’s dilemma where each bank has a “beggar-thy-neighbor” incentive to behave riskily, leaving the industry worse off as a whole.

Additionally, megabanks seem to be getting bigger. Since the repeal of Glass-Steagall and after the enactment of Dodd-Frank the five largest banks have approximately doubled their percentage of national consumer deposits and total assets. Many feel the industry, and all of us along with it, are vulnerable to another collapse. Perhaps the government will reinstall the separation of commercial and investment banking that stood from 1933 to 1999. Perhaps regulators will leash Wall Street. They may not need to. The free market may still reach a more stable state without draconian government intervention.

Community banks suffered proportionally less than the rest of the industry in the aftermath of the Financial Crisis. The FDIC’s Community Bank Development summary of 2012 states “community banks showed continued improvement in financial performance following the disruptions associated with the recent financial crisis. Problem loans and failures declined in 2012, while their pretax profitability was the highest since 2007.”

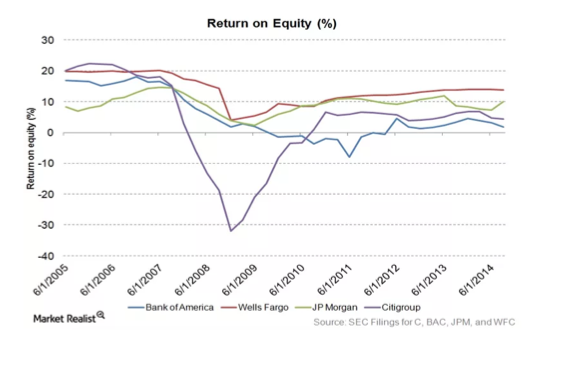

Bulge Bank ROE from 2005-2014. (Courtesy of Marketrealist.com)

Bank of Prairie Village ROE from 1992-2010. Note: BPV transitioned to its new location in 2003. (Courtesy of usabankinfo.com)

Community banks are progressing in terms of market share due to their stability attributable to three main factors:

- The ability to act quickly and unilaterally. Bolen tells a story that exemplifies this: “I came in on a Sunday night and I looked at my bond portfolio and I was looking at how my mortgage-backed securities were performing. Not performing the way they thought they would … so on Monday morning I sold all those bonds,” Bolen continues, “All those investment bankers came back from Martha’s Vineyard, the Hamptons, or Nantucket in September and did the same thing I did, and did the same thing all at once.” This kind of decisive action is not always possible when board meetings or corporate bureaucracy slow down the process.

- Community banks such as BPV usually do not engage in the same dicey speculative practices as larger financial institutions. They do not make quite as much money off net interest margins, but community banks can be at much less risk of an extinction level event (such as the housing bubble bursting). Their structures insulate them from some market fluctuations and allow them to grow more sustainably. “We don’t have a lot of overhead. We don’t have loss,” Bolen points out, “no one deal is going to make me or break me.”

- Community banks have the support of their community and local government. “Client loyalty is major. If you work with your clients everything else will fall in to place”, says Bolen.

If community banks continue to gain traction, the whole economy may be better for it.

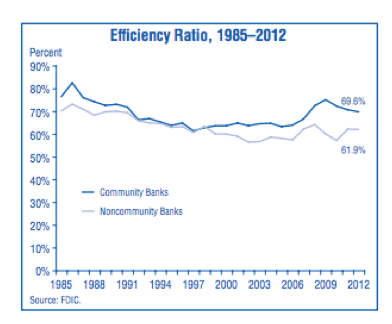

Historically, community banks have outperformed others on a per-dollar basis. (Courtesy of FDIC.)

Some Final Questions for Dan Bolen

NC: Do you have any advice for big banks?

DB: They should decide whether they want to be a traditional commercial bank or investment bank. They should not be betting or speculating with their depositor’s FDIC insured deposits.

NC: Should Financial Ethics be taught at business schools? Should the subject be made mandatory for BBA and MBA finance majors?

DB: Virtually every financial crisis can be traced to greed and rank speculation based on the desire to make money overnight with very little effort. Business ethics should be required- but with a much greater focus on economic history and the dangers of speculation. There should be greater understanding as to why anti-trust rules are important. Large concentrations of wealth and power tend to use their resources to reduce smaller competitors-usually in the name of efficiency. There is a very fine line between striving for corporate efficiency and seeking monopolistic power to protect inefficiency. The rules separating this ethical dilemma are the anti trust laws such as the Sherman Act. Every student of business should understand this, so they in turn can use this knowledge in their career leadership.

NC: Do you believe what you do for the community is an example of corporate citizenship or something else?

DB: By definition, our success is tied to our community’s success. Our bank will not enjoy success, if our community does not thrive. As such community banking and community involvement are so intertwined good corporate citizenship is virtually a byproduct of being a classic community banker. The same thing is true for all small businesses. Ideally, the owner of a business should live in the community in which the business operates. This used to be the way it was. Unfortunately so many small business owners sold and moved away or were forced out by national companies operating on the edge of anti trust laws, that corporate citizenship becomes a challenge. It is hard for a national corporate manager who will only live in a community for a few years and who answers to some Private Equity Fund in New York to want to spend the time and effort to promote his or her community. He or she would rather spend time on vacation or at the second home in some resort setting.

In short, what I do is corporate citizenship, but it is also an investment in my community in hope this investment proves a long-term benefit for my clients, their children and grandchildren. Corporate Citizenship to me is making our community a place where people want to raise their kids, and one in which those grown kids will want to return after college to repeat the cycle.

Finally, I applaud the Seven Pillars Institute for framing and seeking answers to the most challenging issues confronting the business community.

Moving Forward

How might a more stable, simple, and ethical financial system become the norm? There are three possibilities:

- The first is more government intervention. This can come in the form of regulations or incentives. It may be advantageous for the federal government to impose harsher restrictions on debt-to-asset ratios, further ban certain practices, or flex its anti-trust muscles and actually break up big banks. However, these actions are likely to be seen as government overreach. Incentives are often more effective and favorably viewed. Better tax breaks and other fiscal stimulus for community banks can be beneficial. The government can direct taxpayer dollars from bulge bracket bank safety nets to an incentive program that supports the growth of community banks. These actions would not be without precedent. The U.S. Department of the Treasury promotes a similar incentive program, providing financial support for Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs) that bring financial establishments to underserved This initiative is be similar, except it exists to help promote community banks in poorly served metropolitan areas.

- The second possibility is that big banks learn some lessons from their smaller counterparts. A more localized approach can create a strong ethical foundation and a culture where clients matter. When clients are the priority, banks stick to their core competencies and grow in a more stable way while reinvesting in the community. Big banks can emulate this without a completely throwing out of their systems and without incurring massive losses in the transition. The megabanks already have branches all over the country. They can grant their branches additional autonomy and allow them be run more like community banks. This will be a true example of corporate citizenship.

- The third possibility is community banks continue to thrive and proliferate to the point where together, they can compete with Wall Street. This alternative is challenging because large national banks tend to prevail for similar reasons as Wal-Mart overcoming its smaller competitors – branding, convenience, and the market power. Large, established corporations and oligopolies are tough to defeat, but are not invincible. “Everybody wants the filet mignon … but at the McDonald’s price. The more you understand what we’re trying to give you, the more you understand the value proposition”, suggests Bolen. If consumers begin choosing their closest community bank as opposed to the familiarity and synthetic convenience of the megabanks and their ubiquitous ATMS, a grassroots change in the financial system is feasible.

In summary: Community banks are substantially different from larger banks in terms of function, structure, and ethical performance. There is reason to believe these differences make community banks more desirable for the individual banking consumer and the economy as a whole. Megabanks often treat their clientele as a means to profit and not an end in themselves. Community banks allow for localized, robust, mutually beneficial corporate citizenship.

The Bank of Prairie Village states: “an educated banking consumer is our best client.” This declaration should be more broadly applied. An educated banking consumer is the best for the integrity of the banking industry as a whole. The more we learn and understand about our banking options, the better off we will all be. Ultimately, the responsibility to shape finance in America lies in the hands of the public.

-x-

Works Cited

- “About Community Banking.” ICBA. Independent Community Bankers of America, n.d. Web. ] June 2015.

- 2. The Bank of Prairie Village. N.p., n.d. Web. June 2015. <http://www.bankofprairievillage.com/>

- Blasingame, Jim. “A Community Bank Is Not A Little Big Bank.” Forbes. Forbes Magazine, Apr. 2013. Web. June 2015.

- Cecchetti, Stephen G. “Dodd-Frank: Five Years After.” TheHuffingtonPost.com, n.d. Web. June 2015.

- “Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.” FDIC: Community Banking Initiatives. N.p., n.d. Web. June 2015.

- Gustke, Constance. “Community vs. Big Banks | Bankrate.com.” Bankrate, n.d. Web. June 2015.

- Katz, Alyssa. “Housing Is Local, Lending Should Be, Too.” The American Prospect, 17 Apr. 2009. Web. June 2015.

- Prins, Nomi. “Ten Reasons Not to Bank On (or With) Bank of America.” Truthout. N.p., Oct. 2011. Web. June 2015.

- Prins, Nomi. “Risk Is Best Managed From the Bottom Up.” The American Prospect. N.p., n.d. Web. June 2015.

- Schaefer, Steve. Five Biggest U.S. Banks Control Nearly Half Industry’s $15 Trillion In Assets. Forbes Magazine, Dec. 2014. Web. June 2015.

- “United States Census Bureau.” Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas Main. N.p., n.d. Web. June 2015. <https://www.census.gov/population/metro/>.

- Well, Dan. “NY Fed’s Dudley Sees ‘Cultural, Ethical Failures’ at Major Banks.” Newsmax. N.p., 13 Mar. 2014. Web. June 2015.