The Vatican Bank: Conforming to Caritas in Veritate?

The Institute for Religious Works (IOR), commonly known as the Vatican Bank is one of the most secretive and controversial financial institutions in the world. Since the inception of the modern Bank in 1943, the Vatican Bank has faced a series of scandals relating to its role in the Second World War, accusations of money laundering and its role in the collapse of Banco Ambrosiano in 1982. However, what makes these scandals and accusations particularly interesting is that the Vatican Bank operates within the Catholic Church, an organisation with its own tradition of financial ethics developed over multiple centuries. Pope Benedict XVI’s encyclical, Caritas in Veritate represents the most recent expression of Catholic thought relating to financial ethics. This article considers whether these scandals directly contradict the ethical stance of the encyclical and whether this in turn undermines the Vatican Bank’s ethical standing.

The Vatican Bank: What is it and how does it work?

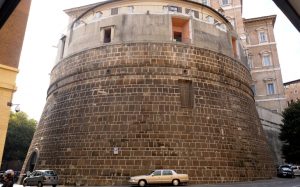

The name ‘Vatican Bank’ is a somewhat misleading name as it implies the Vatican Bank is heavily integrated into the Holy See (the microstate consisting of Vatican City). In fact, the Vatican Bank is a privately held bank, rather than a state-owned bank, and therefore its assets are not directly connected to the Holy See. Despite the Vatican Bank’s position as a private financial institution operating within the Vatican, the Bank is managed by a council of cardinals and the Pope is the Bank’s sole shareholder. The Bank is also officially monitored by the Vatican’s Financial Information Authority and any profits the Bank makes are left at the disposal of the Vatican.

Unlike other commercial Banks, the Vatican Bank does not have any branches or tellers and it offers very few of the financial services which other banks offer, such as securities or financial products. Instead the Bank safeguards the assets of the Catholic Church, for individuals within the Church as well as Catholic Institutions.[i] The Vatican Bank also offers low interest loans to branches of the church for construction and maintenance projects.

Ethical scandal and the Vatican Bank

So far it is difficult to see how the Bank’s operation might be ethically questionable, as the Vatican Bank is primarily concerned with the finances of Catholic institutions and offers very few services. However, the Bank has been involved in a number of high-profile scandals, which draw into question its relationship with Catholic ethical thought.

Money laundering and illegal money transfers

One of the reoccurring questions surrounding the Vatican Bank is its role in money laundering. Historically this has revolved around states using the Vatican Bank’s status for large financial transactions. In particular, the role the Bank played during the Second World War is criticized, as it is alleged the Bank was used to hide illegal gold from Croatia in the final years of the Second World War.[ii] This allegation was the focus of a court case in the United States which was finally dismissed in 2011 due to the sovereign immunity of the Vatican Bank.

It also is alleged that during the Cold War the Vatican Bank was used to channel funds by the United States to support Guerrilla fighters in Nicaragua and anti-communist organisations in Eastern Europe. Central to this allegation is the role the Vatican Bank played as the main shareholder of Banco Ambrosiano, an Italian bank which collapsed in 1982. It is through this Banco Ambrosiano that funds were allegedly channelled to Nicaragua and Poland, with a subsidiary also allegedly supplying funds to Argentina during the Falklands War. Following the Bank’s collapse, the Vatican Bank was drawn into a debate about who ought to pay the outstanding debts accrued by Banco Ambrosiano. The Vatican Bank made a substantial contribution towards these costs although a majority of the debt was taken over by the Italian government and the Vatican Bank refused to accept any liability for the collapse. No criminal proceedings were lodged due to the diplomatic immunity of those involved within the Vatican Bank.[iii]

While these accusations of money laundering are state-centric, there also are accusations the Vatican Bank’s status as an offshore financial centre has been used by individuals and organisations to launder money, particularly from Italy. Italian investigations into money laundering through the Vatican Bank began in 2009. While investigations from Italian officials have since concluded, these issues illustrate how money laundering has followed the Vatican Bank into the 21st century.

The Bank has initiated a series of reforms to make it more compliant with international Banking practices, including the creation of the Holy See’s Financial Intelligence Authority. There also were a number of high-profile resignations including the Head of the Vatican Bank in 2012. In 2014, Pope Francis also sacked four of the five Cardinals charged with managing the Bank because of corruption allegations. In June 2014, the Pope fired the five man board of the Financial Information Authority (AIF), the Holy See’s internal regulatory office. Pope Francis replaced the all male Italian board with four financial experts including a woman for the first time.

Transparency

While concerns about money laundering and illegal money transfers have flared up periodically over the last forty years, there also are ongoing concerns the Vatican Bank is not transparent in its operations. This lack of transparency is partly caused by the ownership structure of the Vatican Bank.The Bank’s sole shareholder is the Pope, and the institutions charged with ensuring its transparency are located within the administration of the Holy See itself. These institutions, like the Financial Intelligence Authority, are also relatively new constructs – for most of the twentieth century there was little to no oversight of the Bank’s behaviour. This lack of transparency is in itself a reason to doubt the financial practices of the Vatican Bank, however it has fed into other scandals at the Vatican, such as the accusations of money laundering.

Financial Ethics and Catholic thought: Caritas in Veritate

Clearly the Vatican Bank was involved in a number of high-profile scandals which call into question the Bank’s ethical principles. However, as a bank whose work occurs primarily within a religious organisation, the Vatican Bank is subject to ethical standards which would not apply to a secular financial institution. How these ethical standards factor into the Bank’s behaviour will be discussed shortly. First though, we need to establish what ethical values should be expected from an institution operating within the Catholic Church. While there are many possible sources, the most relevant for a post-global financial crisis analysis is Pope Benedict XVI’s 2009 encyclical Caritas in Veritate.

The 2009 encyclical from the now retired Pope Benedict XVI, represents the most recent expression of Catholic thought relating to financial ethics. While the entire document is concerned with good ethical practices, the third chapter of the encyclical deals specifically with the question of financial ethics. There are four key aspects of Pope Benedict XVI’s encyclical chapter on economic development; excessive individuality, justice within the market, the need for new business models and the misdirected effects of globalisation. It is these four basic ideas which are explored within this section in order to understand the broader notion of good financial behaviour within Catholic ethical thought.

Excessive Individuality

The first core idea which Pope Benedict explores is the notion modern economic thought is too closely equated with the behaviour of the individual and that selfishness follows as a result. As Pope Benedict describes, “modern man is wrongly convinced that he is the sole author of himself, his life and society.”[iv] This individual-centric world view leads to selfishness and an excessive focus on material well-being, to the detriment of society. The solution, Pope Benedict argues, is to replace this obsession with the individual, and the selfishness that follows, with an economy based upon the principle of charity and giving. By focussing more on charity, economic actors can begin to create a more ethical and just economy, rather than one based on self-interest.

Justice within the Market

Building upon this notion of just behaviour within the economy, Pope Benedict moves from focussing on the individual to considering the role of the market as a whole. The criticism levelled here is that the market is focussed solely on the notion of commutative justice. Commutative justice refers to the exchange of goods and services which guide the economy. Without rejecting this model of justice, the Pope argues that distributive justice and social justice must also guide economic activity. These two broader notions of justice require locating economic activity within a social context, rather than treating it as an isolated system concerned solely with commutative justice. This also requires moving beyond commercial logic to a fuller pursuit of the common good.

New Business Models

Having explored the notion of justice within the economy, Pope Benedict goes on to consider how this notion should translate into new methods of conducting business. In particular, the Pope attacks the model of shareholder-based ownership of companies. This model, whereby the management of a firm is held by a professional class of managers on behalf of shareholders (often faceless financial institutions) is criticised for being too divorced from social conditions. The Pope argues the alienation that occurs through this management process leaves companies separated from the communities they operate in and oblivious to their social environment. This analysis features heavily in the discussion of outsourcing which the Pope argues is evidence of the separation between a profit-seeking management and the social environment in which firms operate. However, the Pope states there is a growing understanding that firms must be more in tune with the social conditions within which they operate. The Pope also claims this change has already been undertaken by a few “far-sighted managers”[v] who recognise the importance of the social conditions under which firms operate. By focussing excessively on profit, firms are stuck in old business models that posit the importance of short term gains at the expense of long-term sustainability.

Misdirected Effects of Globalisation

Finally, Pope Benedict moves from the specific role of outsourcing to a more general discussion on the role of globalisation. The key ethical judgement here is that globalisation is neither a force for good nor bad, but rather a tool whose ethical value is determined by those wielding it. Whereas outsourcing is an example of how globalisation damages communities, there are also many examples of how globalisation can strengthen the bonds between communities and within the economy as whole. The selfishness of those in developed countries and the limited role of justice within the market have created a misdirected globalisation where the global poor are deprived from the tools to alleviate poverty. By refocussing globalisation on those who can benefit most from it, rather than those who have already benefitted, globalisation might become a force for good. These four themes define the third chapter of Caritas in Veritate and represent the clearest expression of Catholic financial ethics in the early 21st Century.

At the time of publication, the themes contained within the encyclical were well received. The encyclical came shortly after the global financial crash of 2008 and many of the themes of the third chapter critique free market fundamentalism and unbridled capitalism. Likewise, the encyclical is credited with creating greater impetus for securing the economic development of poor states in the global south.

Does the Vatican Bank conform to the ethical principles advanced by the Catholic Church?

While the encyclical of Pope Benedict XVI has clearly motivated some change for the better within international development, the question remains as to whether the Vatican Bank, whose sole shareholder is the Pope himself, complies with these ethical imperatives. This analytical section will approach those four themes from Caritas in Veritate and consider whether each of those scandals already outlined is in contradiction to the ethical principles outlined by Pope Benedict XVI.

The first group of scandals outlined above was the accusation of money laundering and illegal money transfers; cases in which the Vatican Bank was used to conceal illegal activities. Money laundering of any kind immediately violates the idea that good financial practice involves awareness of the social environment. The accusations in recent years of money laundering from Italy reveals how the Vatican Bank is used to avoid Italian law. As a result, the Vatican Bank is avoiding the laws which govern the rest of Italy and the Italian communities which surrounds the Vatican. It was also the Italian government which was left to pick up the majority of costs associated with the collapse of Banco Ambrosiano, despite the Vatican Bank being the largest shareholder of the Bank. It can hardly be claimed that the Vatican Bank has a community focus when it is actively involved in laundering money from the country which surrounds it on all sides.

Similar problems arise when we consider the Vatican Bank’s role in funnelling money to international conflict zones. Not only does this represent a clear disregard for the communities affected by the Vatican Bank’s decisions, but it also shows how the force of globalisation have been misused by the Bank. Globalisation has created the conditions under which millions of dollars can be transferred instantly to bank accounts on the other side of the world. It is this factor which made it possible for the Vatican Bank to transfer finances to Nicaraguan rebels or to the Argentinian Government during the Falklands War. The ability to transfer large sums of money instantly across the planet reflects the power of globalisation and how the Vatican Bank has used this power for illegal and unethical projects.

Complementing these concerns of illegal money transfers and laundering is the lack of transparency which accompanies the Vatican Bank’s financial behaviour. In fact, Pope Benedict’s encyclical specifically states that “transparency… cannot be ignored.”[vi] He goes on to state the lack of transparency from financial institutions was a key factor in the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. Given this strong account of the value of transparency, it is troubling the Pope heads such an opaque financial institution.

As mentioned earlier, part of the cause of this lack of transparency within the Vatican Bank is the fact that the Pope is the sole shareholder of the Bank, meaning it falls into the old methods of doing business which Pope Benedict described. Supporters may argue that turning profits over to the Vatican rather than to anonymous shareholders is a more ethical business model. Yet the model still relies on the patterns of business ownership which allegedly contribute to the selfish and individualistic attitude guiding modern investments. Despite the Bank’s stated preference for low risk lending to religious institutions within the Church, it has also engaged in highly risky investment strategies, such as its investment in Banco Ambrosiano. This continues the trend which Pope Benedict saw as the result of the excessive individualism which guided old business models. The Pope’s role as the sole shareholder, the questionable business arrangements which follow and the overall lack of transparency created by this arrangement further reveal how the Vatican Bank does not match the ethical standards set by Pope Benedict XVI.

Vatican Bank: conforming to Caritas in Veritate?

The Vatican Bank is apparenty breaching the ethical standards for good finance which the retired Pope Benedict advanced in Caritas in Veritate. The Bank’s involvement in a number of specific scandals as well as the broader trends of money laundering, illegal money transfers and the lack of transparency run counter to those ethical standards which Pope Benedict outlined in his encyclical. That being said, there are changes underway at the Vatican Bank. Not only is the Bank more transparent and regulated today than at any other time in its history, but the high-profile sacking of managers and Cardinals suspected of corruption further suggests the Vatican under Pope Francis is responding to these ethical concerns. However, the Bank still does not fully conform to the ethical practice advanced by Pope Benedict, which means the Vatican Bank is failing to live up to the ethical standards of its sole shareholder as well as those of the institutions it is charged with supporting.

Bibliography

Cumming, Jean (1997) “Holy Finance!” Canadian Banker 104.2

Hart, Reuben (2006) “Property, war objectives, and slave labor claims: the Ninth Circuit’s political question analysis in Alperin v. Vatican Bank.(Ninth Circuit Survey)” Golden Gate University Law Review Vol.36(1-3)

Laurent, Bernard (2010) “Caritas in veritate as a social encyclical: a modest challenge to economic, social, and political institutions” Theological Studies 71.3

Pope Benedict XVI (2009) Caritas in Veritate- Encyclical Letter of his Holiness Benedict XVI accessed online from: http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/benedict_xvi/encyclicals/documents/hf_ben-xvi_enc_20090629_caritas-in-veritate_en.html

Schoepner, Cynthia (2007) “Vatican Bank” Encyclopaedia of Business Ethics and Society ed. Robert Kolb Sage Publications

Notes:

[i] Cumming, Jean (1997) “Holy Finance!” Canadian Banker 104.2 pg. 31

[ii] Hart, Reuben (2006) “Property, war objectives, and slave labor claims: the Ninth Circuit’s political question analysis in Alperin v. Vatican Bank.(Ninth Circuit Survey)” Golden Gate University Law Review Vol.36(1-3) pg. 17

[iii] Schoepner, Cynthia (2007) “Vatican Bank” Encyclopaedia of Business Ethics and Society ed. Robert Kolb Sage Publications

[iv] Pope Benedict XVI (2009) Caritas in Veritate- Encyclical Letter of his Holiness Benedict XVI Chapter Three, Paragraph 34

[v] Ibid, chapter Three Paragraph 40

[vi]Ibid Chapter Three Paragraph 36

Photos: Reuters and CNS/Catholic Press Photo