JPMorgan Chase: Code of Ethics and Revisions Since the 2008 Financial Crisis

By: Daniel Strong

JPMorgan has an extensive Code of Ethics, which appears to be well polished, written and executed. There are adequate policies designed to encourage compliance and whilst changes have only occurred to the Code of Conduct, they have been very positive in nature. Despite this, there appears to be no change in the frequency of ethical issues facing the company which suggests different types of intervention are needed.

There are three parts to this article. The first outlines relevant background information of JPMorgan, including its ongoing ethical and legal violations. The second section examines the current code of ethics adopted by the company, consisting of a Code of Conduct, a Code of Ethics and more restrictive codes for certain subsidiaries. While the codes have a distinct concern about the company’s reputation and legal compliance, they cover a wide variety of topics including human rights, the giving of gifts and intellectual property. This section also compares the current code of ethics to previous versions, noting one major change in the Code of Conduct in 2013. The third and final section explores how the code is implemented in practice and how compliance is encouraged including membership of certain organisations, the availability of reporting services and auditing measures.

Section I – Background Information

Headed by Chief Executive Officer (CEO) Jamie Dimon, American based JPMorgan Chase & Co., was founded in 1799 by its predecessor company the Manhattan Company. It was the first billion dollar corporation in 1901 and has steadily grown over time, merging with and acquiring other companies including the Chase Manhattan Corporation, which is now included in the corporation’s name. The company is primarily concerned with finance related activities, including commercial banking, market services and investment banking (JPMorgan Chase & Co 2015a; JPMorgan Chase & Co 2015b)

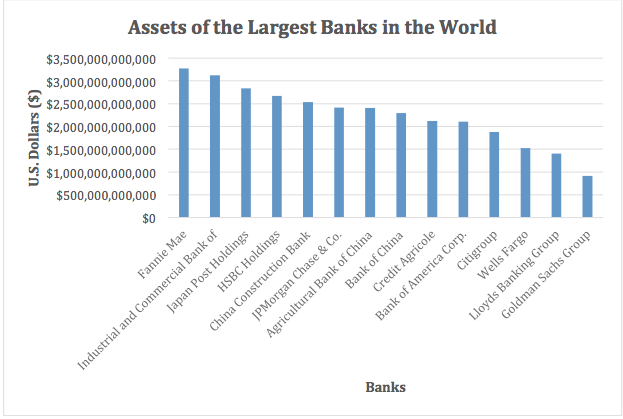

The bank is one the largest companies in the world, ranked as the fourth largest public company by Forbes (Forbes 2014), and ranked thirteenth and fifty seventh in the Fortune 500 and Fortune Global 500 respectively. It owns around 2.4 trillion dollars’ worth of assets, making it comparable with some of the biggest banks in the world (Fortune 2014a; Fortune 2014b; Fortune 2015).

Figure 1: Forbes 2014

JP Morgan’s net income and revenue were 21.8 billion and 97.9 billion U.S dollars respectively in 2014 (JPMorgan Chase & Co 2014a). To put this in perspective, the New Zealand government received and spent 89.4 billion and 92.2 billion New Zealand Dollars respectively in the same year (Treasury 2014). In US dollars this comes to about 67 and 69 billion U.S. dollars.

Possessing the kind of cash flows comparable to a modern state like New Zealand highlights the size of the corporation itself and the global economic influence JP Morgan is capable of wielding. Considering this, it is highly relevant how the company acts from an ethical standpoint.

Recent Ethical Issues

JPMorgan Chase & Co has been repeatedly involved in illegal and unethical behaviour since the global financial crisis of 2008 with no signs of remission. Some of these instances (but by no means all) are listed below.

- February 2015: Two JPMorgan Chase & Co employees are charged for assisting an ‘aggravated breach of trust’ in selling risky products to the German city of Pforzheim and allegedly misleading the city council over the matter (Matussek 2014).

- January 2015: JPMorgan Chase & Co along with Wells Fargo is charged by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and the Maryland Attorney General with running an ‘illegal marketing-services-kickback scheme’. Customers of the bank are being manipulated into using one particular company by at least six employees who were rewarded with cash and other assets for doing so. The penalties for this could cost the company $600,000 U.S. dollars (Consumer Financial Protection Bureau 2015).

- November 2014: The Company, along with the Royal Bank of Scotland, HSBC Bank, Citibank and UBS are collectively fined £2.6 billion pounds for rigging foreign exchange markets described as part of a ‘free for all culture’ (Treanor 2014).

- July 2014: JPMorgan Chase & Co is fined $650,000 dollars for ‘repeatedly submitting inaccurate Large Trade Reports’ by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (Commodity Futures Trading Commission 2014).

- October 2013: The Company is ordered to pay a $100 million dollar penalty by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission for ‘manipulative conduct’ in dumping large amounts of credit default swaps (Commodity Futures Trading Commission 2013).

- September 2013: The Securities and Exchange Commission fines JPMorgan Chase & Co $920 million for ‘misstating financial results’ and failing to implement controls to prevent their ‘traders from fraudulently overvaluing investments to conceal hundreds of millions of dollars in trading losses’ (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 2013)

- August 2013: JPMorgan Chase & Co is ordered to pay $23 million dollars for the misuse of customer funds in buying Lehman Brothers notes in ‘reducing its own exposure’ despite having knowledge of company’s problems which preceded its bankruptcy (Stempel 2013). This after being fined an additional $20 million dollars earlier in April 2012 by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission for the same case (Commodity Futures Trading Commission 2012a).

- September 2012: JPMorgan Chase & Co is fined $600,000 dollars for exceeding speculative position limits trading on the InterContinental Exchange U.S (Commodity Futures Trading Commission 2012c).

- March 2012: JPMorgan Chase & Co is fined $140,000 dollars for a non-competitive and ‘fictitious’ ‘prearranged trade’ where a customer was allowed to trade on both sides of a transaction (Commodity Futures Trading Commission 2012b).

- July 2011: The Company is fined a total of $228 million for ‘rigging at least 93 municipal bond reinvestment transactions in 31 states’. This was achieved by illegally arranging to gain information on competitor’s positions (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 2011).

- November 2009: The Securities and Exchange Commission penalises the Company a combined total of $722 million dollars for conducting an ‘unlawful payment scheme’ where Jefferson County (Alabama) officials were paid in order to ‘win business and earn fees’ with the cost of the illegal payments passed onto the county in higher interest rates (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 2009).

- September 2009: The Company is fined $300,000 dollars for drawing upon customer funds breaching the separation of customer and firm funds, as well as failing to report this breach in a ‘timely’ manner (Commodity Futures Trading Commission 2009).

Section II – The Written Code

What can be considered JPMorgan Chase & Co.’s code of ethics contains both an employee Code of Conduct and an accompanying Code of Ethics. There are also further Codes of Ethics prescribed to particular subsidiaries.

Code of Conduct

The Code of Conduct as of writing, is reasonably lengthy (49 pages) and covers the variety of topics with a noticeable degree of detail. The code is broken into five sections entitled ‘Our Heritage’, ‘A Shared Responsibility to Our Customers and the Marketplace’, ‘A Shared Responsibility to Our Company and Shareholders’, ‘A Shared Responsibility to Each Other’ and ‘A Shared Responsibility to Our Neighbourhoods and Communities’ (JPMorgan Chase & Co 2014).

The first section ‘Our Heritage’ is a general introduction to the code, telling employees to ‘conduct business ethically and in compliance with the law everywhere we operate’ including co-operation with authorities, with the law to be upheld according to its ‘letter’ as well as its ‘spirit and intent’ (with employees expected to know all laws and regulations affecting them). The reach of the code itself is firmly established as a ‘term and condition of employment’ of all employees of the company, although there is a slightly ambiguous exception to any ‘separate legal entity’ which must first be approved as subject to the code. Employees are not only required to follow the code, but also report any others suspected of breaking it (JPMorgan Chase & Co 2014b: 2-9).

This section also sets out rules surrounding the use and dissemination of information. All information, both personal and company-related in nature is to be considered confidential and disclosed on a ‘need-to-know basis’. This includes disclosing information to family and friends, other parts of the company (with some exceptions) and information on previous employers (which should not be revealed to the company) (JPMorgan Chase & Co 2014b: 5-7).

The second section, ‘A Shared Responsibility to Our Customers and the Marketplace’ primarily deals with legal compliance. Relating to insider trading, It contains strict guidelines on the control of Material Non-Public Information (MNPI), with employees banned from trading in any accounts when they possess related MNPI and barred from passing this information along to anybody in any form unless with explicit approval. Furthermore, it restricts employees’ private trading activities from being ‘short term or speculative’, risky or outside an employee’s ‘financial means’ (JPMorgan Chase & Co 2014b: 11-13). Employees are also restricted from investing in clients or suppliers of the company, and must disclose companies they do hold securities in, if asked to conduct any business with them (JPMorgan Chase & Co 2014b: 14).

This focus on adherence to the law continues with employees required to comply with anti-tying laws, avoid and report any money-laundering activity, and to comply with economic sanctions placed by the United States and its allies as well as anti-boycott laws. With a company ‘commitment’ to antitrust laws employees cannot fix prices, conduct bid rigging or group boycotts, separate customers or territories or limit services to particular areas (JPMorgan Chase & Co 2014b: 15-16).

The offer or acceptance of bribes is also forbidden ‘if it is intended or appears intended to obtain some improper business advantage’ including bribes that are considered common in some countries to ‘expedite performance’. Third parties also are not to be asked to conduct any governmental or business dealings on behalf of the company (JPMorgan Chase & Co 2014b: 17).

The third section, ‘A Shared Responsibility to Our Company and Shareholders’ adds further limits on employee actions. It outlines the company’s policies on intellectual copyright, such that any business-related ideas ‘created in or outside work belongs to the company’ and employees must assist the company in enforcing this ownership (JPMorgan Chase & Co 2014b: 21).

Employees also are expected to handle information responsibly, with a particular focus on ‘accurate record keeping’, involving personal expenses etc. Employees must provide ‘complete, accurate, timely and understandable’ information to authorities and not ‘misrepresent or omit material facts’ (JPMorgan Chase & Co 2014b: 21-22).

The giving and receiving of gifts is given a lot of attention, with strict guidelines likely related to anti-bribery concerns. Gifts cannot be solicited in appreciation for good service or thanks or ‘as a tool to influence or reward’. Gifts must have some sort of ‘customary justification’ such as a weddings, or stationary with company advertising on it. If goods are perishable they must not be extravagant and must be shared with colleagues. Goods over the value of 100 U.S. dollars are not to be accepted. Some types of gifts are also explicitly prohibited such as straight cash or gift cards (JPMorgan Chase & Co 2014b: 26-28).

There are also some expected policies against romantic relationships, working with relatives, engaging in business transactions with families and friends as well as using company resources to access inappropriate material, gamble, install risky software etc. (JPMorgan Chase & Co 2014b: 20).

Previous limitations on personal finance are extended with the expectation employees conduct this activity with ‘responsibility’ and ‘integrity’. This includes acting as a guarantor for clients, customers or co-workers, avoiding any preferential treatment, acting as a personal fiduciary for anyone not family or a close friend, involvement with competitors, and the use of disreputable sources of loans (JPMorgan Chase & Co 2014b: 22-24). Employee lives are also addressed with restrictions on anything that could be regarded as a conflict of interest, representing the company unless ‘explicitly authorized’, putting not for profit activities ahead of their job, ensuring social media usage does not reflect on the company as well as a ‘pre-clearance’ requirement for public testimony, talking about their jobs, and speaking engagements (JPMorgan Chase & Co 2014b: 24; 28-30). This is on top of the requirement in the second section of the code that employees cannot encourage anyone to leave the company (JPMorgan Chase & Co 2014b: 15).

The fourth section, ‘A Shared Responsibility to Each Other’ continues the theme of restrictions on employee’s behaviour. Unsurprisingly it outlines zero tolerance for discrimination, the use of drugs or alcohol at work, bullying, violence and sexual harassment (JPMorgan Chase & Co 2014b: 33-35).

The final section ‘A Shared Responsibility to Our Neighbourhoods and Communities’, rather predictably governs employee behaviour in the community. A clear line is drawn regarding the company’s political involvement, with employees allowed to be politically involved but completely separate these activities from the company. Activities such as meetings with government officials need to be pre-approved (JPMorgan Chase & Co 2014b: 37-38). Although charitable work is not to interfere with their jobs, employees are encouraged to be involved in helping the community and being a ‘global citizen’, with the company expressing support for ‘environmental stewardship’ and human rights (JPMorgan Chase & Co 2014b: 38-40).

Focus of the Code of Conduct

The code itself seems to be based on two primary concerns: compliance with the law and the upholding of the company’s reputation. The first is demonstrated for instance, by the mention of antitrust laws, accurate record keeping and so forth. The second is underlined in a slightly more implicit manner, but still visible (particularly in the restrictions of employee’s behaviour). The clearest example of this is in the introductory letter from the company CEO Jamie Dimon. He mentions how employees should act with integrity not only because it is the moral thing to do but also because ‘it is essential to protecting our firm’s reputation’ reminding readers that ‘once a company’s reputation is harmed, the effects are enduring’ and that even ‘a perceived ethical transgression can permanently damage any company’ (JPMorgan 2014b: II)

Whilst the latter of these two concerns has little to do with ethics, it is an understandable position from a business perspective, although it does seem to be excessively stressed throughout the code. One does wonders whether this concern (and its strict requirements on employee behaviour) is driven by a negative public perception of financial institutions (and its knock-on effects on investors) in the wake of the global financial crisis and recent public relations disasters mentioned previously.

The first concern, adherence to the law, is a relevant ethical imperative, but it seems unwise to consider the law the ultimate judge of what is moral. In that case, what does the code have to say about ethics beyond the company’s legal requirements?

We can immediately discount ethical requirements of the code such as discrimination or bribery because although they are certainly morally justified, they are also required by law and do not give an unfiltered insight into the ethical commitment of JPMorgan.

However, some specific rules and interests could be considered ethical. Bans on some forms of bullying and activity at work that may not fall within the law, the promotion of human rights and environmental concerns (however vague) and political independence can be thought as ethical outside the confines of the law.

There are also some less specific but still relevant requirements of the code. Employees are told to act with ‘personal integrity’, to the ‘highest standards of ethical conduct’, to never manipulate people, to listen to feedback, to ‘treat others with dignity and respect’ and to act in a ‘fair, ethical and non-discriminatory manner’ (JPMorgan and Chase 2014b: 14; 35; 41). Whilst these could be considered vague, they are still important ethical ideas to promote.

Code of Ethics

The Code of Ethics is short and its requirements ‘supplement, but do not replace, the firm’s Code of Conduct’. Like the Code of Conduct, it is a ‘term and condition’ of employment. Although most of its contents is contained within the Code of Conduct itself, it instructs finance related employees to act in an ethical manner (specifically regarding conflicts of interest) and with full compliance to the law. It specifically targets compliance with regulators such as the Securities and Exchange Commission in filing ‘full, fair, accurate, timely and understandable disclosure in reports and documents.’ Employees are not to ‘coerce, manipulate’ or ‘mislead’ authorities. They also are told to ‘promptly report’ any violation of the code (JPMorgan Chase & Co 2015c).

Similar to the Code of Conduct, the Code of Ethics can be summed up well by its introductory objective in that its purpose is to (JPMorgan Chase & Co 2015c):

“Promote honest and ethical conduct and compliance with the law, particularly as related to the maintenance of the firm’s financial books and records and the preparation of its financial statements”

In other words, the Code of Ethics is primarily concerned with compliance with the law. As with the Code of Conduct this could have ethical and/or self-interested motivations. Considering all the content is already contained within the Code of Conduct, the Code of Ethics as a separate entity seems unnecessary unless its existence is to emphasis compliance with the law as a chief concern (which seems self-interested in motivation).

Subsidiaries

Further restrictions are placed on senior level employees of particular subsidiaries involved in financial markets. It is important to note that these specific codes are required by law, rather than being a company initiative. Some of the rules present in the Code of Conduct and the Code of Ethics are in these specific codes, but there are some additional ones. These employees are required to disclose all securities to the Compliance department as well as all transactions in which they are involved. Senior staff are subject to a minimum holding period of these securities and have a ‘special responsibility’ to ensure the confidentiality of customer’s information. Finally, they are required to keep accurate records including lists of code violations, present and previous codes and people with access to MNPI (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 2007; U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission n.d.).

Revisions to the Code Since the Global Financial Crisis

There appears to be few revisions to the codes described. The publication of a Code of Ethics is first mentioned in a Form 10-K submission to the Securities and Exchange Commission on 31st December 2003 (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 2003: 1). This is confirmed by its first findable presence on an Internet Archive snapshot (of the Company’s website) on the 24th April 2005 (Internet Archive 2015a). Other than a formatting change in 2010 (Internet Archive 2015b), the wording is completely identical.

There also are no apparent or accessible amendments to the specific subsidiary codes of ethics since the Global Financial Crisis.

There are however, four previous Code of Conducts dated May 2009, May 2010, April 2011 and June 2013. Although not stated, there seems to be a policy of annual revision. The content of all versions is similar but there are four important changes to note between 2009 and 2014 versions (JPMorgan Chase & Co 2009).

Firstly, the newest version is more polished, more articulate and better laid out. The refinements are noticeable by the addition of specific examples, decision trees and the added ability to report anonymously to an independent organisation through several methods (JPMorgan Chase & Co 2014b).

Secondly, there is more emphasis on general ethical values in the 2014 version. Treating customers correctly for example, is not explicitly mentioned in the oldest version. Furthermore, there is no mention of either environmental stewardship or an employees obligations to be a global citizen.

Thirdly, although the content is the same, the newest version is much more specific. In the oldest version there is no mention on the use of drugs and alcohol in the workplace, no mention of social media restrictions, no mention of common bribes made to expedite performance, no mention of the inclusion of EU and American sanctions, and clearer guidelines on harassment, which now include specific terms like ‘bullying’ and ‘sexual harassment’ (JPMorgan Chase & Co 2014b: 15-17; 33-34).

Finally, the general tone of the oldest Code of Conduct stresses less (although it is still present) on legal compliance and the protection of the company’s reputation. This may be due to the continued problems with issues of unethical behaviour associated with the company.

The changes between the five versions are as follows.

Code of Conduct Changes 2009 to 2010

Very minor revisions to the code, mostly formatting but does include the provision on social media usage (JP Morgan Chase & Co. 2010: 7).

Code of Conduct Changes 2010 to 2011

This could be best described as an amendment to the 2010 version, with the text being almost identical save for a few additional details. For example, there is now a sharp differentiation between U.S. Government officials, Non-U.S. Government officials, and employees in terms of bribery policy. Employees are also now restricted from investing in ‘private offered unregistered funds organized by the firm’. A summary and conclusion is added as well as an independent reporting service offered through email, telephone and fax (JP Morgan Chase & Co. 2010; JP Morgan Chase & Co. 2011: 4-27)

Code of Conduct Changes 2011 to 2013

The changes constitute most the revisions present between 2009 and 2014. The formatting of the document is changed and the options for employees to report code violations now includes a website alternative. Decision trees and specific examples are also added (JPMorgan Chase & Co. 2013a).

Code of Conduct Changes 2013 to 2014.

The differences between 2013 and 2014 can be compared to the changes between 2010 and 2011, being superficial in nature by reformatting, rephrasing and streamlining the document. Some information is added, such as the differentiation between non-public information and MNPI (JPMorgan Chase & Co. 2014b: 11), and some are taken away, such as a diagram relating to information barriers (JPMorgan Chase & Co. 2014b: 13). The company’s statement on environmental issues is rephrased to perhaps appear slightly less committed, now stating a belief that ‘balancing environmental with financial priorities is fundamental’ (JPMorgan Chase & Co. 2014b: 39).

Section III – The Code in Practice

The rules described in a code of ethics mean nothing without some of form of implementation and encouragement to comply. As such it is prudent to ask what JPMorgan has done to achieve compliance. To start with, there are several methods outlined in the Code of Conduct itself, including its well laid out structure and explicit rules (which leave little room for unethical behaviour or misinterpretation).

The presence of a functioning and independent hotline (with explicit protection for whistle-blowers) able to accessed through fax, telephone, email and the internet (JPMorgan Chase & Co. 2014: 42) is an excellent method to encourage all-important whistle-blowers (Callaghan et al. 2012: 19).

JPMorgan Chase & Co. also encourages compliance through the availability of code specialists to every single employee (who are trained to give clarification on ethical matters), as well as mandatory annual affirmations of understanding, training sessions and severe punishments for breaches (including termination) (JPMorgan Chase & Co. 2014: 2-3). These training sessions and affirmations, if regarded as a ‘priming mechanism’ are useful in the context of promoting compliance (Davidson and Stevens 2013:71). The code also has been translated into several languages and ‘is available on the intranet’ to all employees (JPMorgan Chase & Co. 2014: 8).

JPMorgan Chase & Co. also implements the principles of its Code of Conduct, particularly environmental ones externally, being involved in the following organisations and agreements:

- Equator Principles: promotes minimum principles of ethical behaviour including the reporting of high greenhouse gas emitting projects and the implementation of labour standards (Equator Principles 2013; JPMorgan Chase & Co. 2014c).

- Adoption of UN Declaration of Human Rights: (JPMorgan Chase & Co. 2014c)

- Carbon Principles: agreement to address carbon risks and try to meet energy needs in ‘an environmentally responsible and cost-effective manner’ (Credit Suisse 2015; JPMorgan 2014c)

- Green Bond Principles: Investment in environmentally forward thinking project (JPMorgan 2014c; International Capital Market Association 2015)

- Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative: Full disclosure of payments made by oil, gas and mining companies to governments in order to prevent corruption and conflict (Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative 2015; JPMorgan 2014c)

- United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment: ‘Awareness of environmental, social and corporate governmental (ESG) issues’ (JPMorgan Chase & Co. 2014c; Principles for Responsible Investment 2015).

- Ceres Company Network: Promotion of environmental and social responsibility (Ceres 2015; JPMorgan 2014c).

- The Wolfsburg Principles: Advancement of robust financial frameworks and activities such as money laundering and corruption (JPMorgan Chase & Co. 2014c; Wolfsburg Principles 2015).

The regularly published Environmental and Social Policy Framework also includes specific bans on activities related to child labour, forced labour, resource exploitation on world heritage sites, illegal logging and companies that have no policies against uncontrolled or illegal use of fire in forestry (JPMorgan 2014c: 5-6). Enhanced review processes are also required for certain activities such as hydraulic fracturing (fracking), oil and gas projects, and any business related to palm oil (JPMorgan 2014c: 7-8). Periodic internal audits of policies are conducted to ensure compliance as well as annual environmental sustainability and corporate responsibility reports (JPMorgan & Chase 2014c: 20)

Additionally, the 2013 ‘How We Do Business’ report makes the following claims:

- 16,000 employees added to ‘support our regulatory, compliance and control efforts’ as well as a million hours of training related to these activities (JPMorgan & Chase 2013b: 27).

- Additional 2 billion dollar budget increase for regulatory and control issues as well as 1.7 billion spent on technology related to these activities (JPMorgan & Chase 2013b: 27).

- The Establishment of a firm wide Risk Committee, a firm wide Fidiciary Risk Committee and a firm wide Control Committee in 2012 and 2013 (JPMorgan & Chase 2013b: 28).

Independent audits of the company are also conducted by PricewaterhouseCoopers (JPMorgan Chase & Co. 2015d).

Breaches of the Code of Conduct can result in both reduction of compensation and retroactive retrieval of salaries and bonuses (including equities) even if employees have left the firm, known as claw black provisions (J.P. Morgan 2014d: 25;44-45) . A prime example of this being applied is action taken against employees involved in the market manipulation for which the company was fined in October 2013 (Heineman 2012).

Success or Failure?

Despite these efforts there are undoubtedly ongoing issues within the company, even though the unethical behaviour the company (or its employees) is involved in is clearly forbidden by the code of ethics described. Despite the apparently genuine drive to enforce the code, these efforts don’t appear to have made any difference in reducing these problems. This perhaps reveals cultural tendencies within the institution that are proving difficult to change and that a code of ethics is inadequate in creating an ethical culture. Determining what other methods can be taken outside of a code of ethics should be regarded as an important extension and an opportunity for research.

Not all blame can be placed on JPMorgan however, with its independent auditor fined £1.4 million pounds for failing to conduct its audits properly which would have prevented some the misconduct described (White 2012).

Unchanged code, improved implementation, same culture?

Overall the JP Morgan’s Code of Ethics contains a distinguishing focus on legal compliance and protecting the company’s reputation which complicates an ethical evaluation of the codes.

The revisions to the code itself were either non-existent or minor apart from the significant amendment to the Code of Conduct in 2013, which added much more detail and improved formatting. The implementation of the Code shows JPMorgan Chase & Co. is making noticeable efforts to advance implementation and encourage compliance including an important and easily accessible independent whistle-blowing tool.

Yet, when these efforts are compared to the ongoing ethical problems listed in the first section, it appears the improvements are not sufficient to prevent unethical and damaging behaviour within the institution itself. This suggests more and potentially different types of initiatives are required.

–xxx–

References

Callaghan, M, Wood, G, Payan, J, Singh, J, and Svensson, G. 2012. Code of Ethics Quality: An

International Comparison of Corporate Staff Support and Regulation in Australia, Canada and the United States. Business Ethics: A European Review, 21(1): 15-30

Company Network. 2015. [Online]. Ceres. Available: http://www.ceres.org/company-network [14

February 2015].

CFTC Sanctions J.P. Morgan Futures, Inc. $300,000 for Failing to Properly Segregate Customer Funds

and Failing to Timely Report the Under-segregation to the CFTC. 2009. [Online]. Commodity Futures Trading Commission. Available: http://www.cftc.gov/PressRoom/PressReleases/pr5713-09 [7 February 2015].

CFTC Orders JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. to Pay a $20 Million Civil Monetary Penalty to Settle CFTC

Charges of Unlawfully Handling Customer Segregated Funds. 2012a. [Online]. Commodity Futures Trading Commission. Available: http://www.cftc.gov/PressRoom/PressReleases/pr6225-12 [7 February 2015].

J.P. Morgan Securities LLC Agrees to Pay $140,000 Penalty for Confirming the Execution of a

Prearranged Trade on the CBOT. 2012b. [Online]. Commodity Futures Trading Commission. Available: http://www.cftc.gov/PressRoom/PressReleases/pr6198-12 [7 February 2015].

CFTC Orders JP Morgan Chase Bank, N.A. to Pay $600,000 Civil Monetary Penalty for Violating Cotton

Futures Speculative Position Limits. 2012c. [Online]. Commodity Futures Trading Commission. Available: http://www.cftc.gov/PressRoom/PressReleases/pr6369-12 [7 February 2015].

CFTC Files and Settles Charges Against JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A., for Violating Prohibition on

Manipulative Conduct In Connection with “London Whale” Swaps Trades. 2013. [Online]. Commodity Futures Trading Commission. Available: http://www.cftc.gov/PressRoom/PressReleases/pr6737-13 [7 February 2015].

CFTC Charges J.P. Morgan Securities LLC With Repeatedly Submitting Inaccurate Large Trader

Reports and Imposes a 650,000 Civil Monetary Penalty. 2014. [Online]. Commodity Futures Trading Commission. Available: http://www.cftc.gov/PressRoom/PressReleases/pr6968-14 [7 February 2015].

CFPB Takes Action Against Wells Fargo and JPMorgan Chase for Illegal Mortgage Kickbacks. 2015.

[Online]. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Available: http://www.consumerfinance.gov/newsroom/cfpb-takes-action-against-wells-fargo-and-jpmorgan-chase-for-illegal-mortgage-kickbacks/ [7 February 2015].

Carbon Principles. 2015. [Online]. Credit Suisse. Available: https://www.credit-

suisse.com/ch/en/about-us/corporate-responsibility/banking/international-agreements/carbon-principles.html [15 February 2015].

Davidson, B and Stevens, D. 2013. Can a Code of Ethics Improve Manager Behaviour and Investor

Confidence? An Experimental Study. Accounting Review, 88(1): 51-75.

The Equator Principles: June 2013. 2013. [Online]. Equator Principles. Available:

http://www.equator-principles.com/resources/equator_principles_III.pdf [14 February 2015].

What is the EITY?. 2015. [Online]. Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative. Available:

https://eiti.org/eiti [14 February 2015].

The World’s Biggest Public Companies. 2014. [Online]. Forbes. Available:

http://www.forbes.com/global2000 [3 February 2015].

Fortune 500. 2014a. [Online]. Fortune. Available: http://fortune.com/fortune500/ [3 February 2015].

Global 500. 2014b. [Online]. Fortune. Available: http://fortune.com/global500/ [3 February 2015].

JPMorgan Chase & Co. 2015. [Online]. Fortune. Available: http://fortune.com/company/jpm [3

February 2015].

Heineman, B. 2012. [Online]. Two Cheers for JP Morgan’s “Clawbacks”. Harvard Business Review.

Available: https://hbr.org/2012/07/two-cheers-for-jp-morgans-claw [25 February 2015].

Green Bonds. 2015. [Online]. International Capital Market Association. Available:

http://www.icmagroup.org/Regulatory-Policy-and-Market-Practice/green-bonds/ [15 February 2015].

Code of Ethics. 2015a. [Online]. of Ethics. 2015b. [Online]. of Conduct. 2009. [Online]. JPMorgan Chase & Co. Available:

http://www.jpmorganchase.com/corporate/About-JPMC/document/code_of_conduct.pdf [10 February 2015].

Code of Conduct. 2010. [Online]. JPMorgan Chase & Co. Available:

http://www.jpmorganchase.com/corporate/About-JPMC/document/CodeofConduct_2010Edition.pdf [25 February 2015].

Code of Conduct. 2011. [Online]. JPMorgan Chase & Co. Available:

http://www.jpmorganchase.com/corporate/About-JPMC/document/2011CodeofConduct.pdf [10 February 2015].

Code of Conduct. 2013a. [Online]. JPMorgan Chase& Co. Available:

http://www.jpmorganchase.com/corporate/About-JPMC/document/229048_2013_CodeofConduct_05.31.13_ada.pdf [10 February 2015].

How We Do Business. 2013b. [Online]. JPMorgan Chase & Co. Available:

http://files.shareholder.com/downloads/ONE/3912807319x0x799950/14aa6d4f-f90d-4a23-96a6-53e5cc199f43/How_We_Do_Business.pdf [9 February 2015].

Earnings Releases. 2014a. [Online]. JPMorgan Chase & Co. Available:

http://investor.shareholder.com/jpmorganchase/earnings.cfm [3 February 2015].

Code of Conduct. 2014b. [Online]. JP Morgan Chase & Co. Available:

http://www.jpmorganchase.com/corporate/About-JPMC/code-of-conduct.htm [25 January 2015].

Environmental and Social Policy Framework: April 2014. 2014c. [Online]. JPMorgan Chase & Co.

Available: http://www.jpmorganchase.com/corporate/Corporate-Responsibility/document/JPMC_Environmental_and_Social_Policy_Framework_MAY_FINAL_ada.pdf [14 February 2015].

2014 Proxy Summary. 2014d. [Online]. JP Morgan Chase & Co. Available:

http://files.shareholder.com/downloads/ONE/3912807319x0x741927/944b2966-bacb-4a37-b34e-cdc447ffaa78/JPMC_2014_Proxy_Statement.pdf [25 February 2015].

Company History. 2015a. [Online]. JPMorgan Chase & Co. Available:

https://www.jpmorgan.com/pages/company-history [3 February 2015].

What We Do. 2015b. [Online]. JPMorgan Chase & Co. Available:

https://www.jpmorgan.com/pages/what-we-do [3 February 2015].

Code of Ethics. 2015c. [Online]. JP Morgan Chase & Co. Available:

http://www.jpmorganchase.com/corporate/About-JPMC/code-of-ethics.htm [25 January 2015].

Frequently Asked Questions. 2015d. [Online]. JPMorgan Chase & Co. Available:

http://investor.shareholder.com/JPMorganChase/faq.cfm [14 February 2015].

Matusseek, K. 2015. [Online]. JPMorgan Bankers Charged over $64 Million in Swap-Sale Losses.

Bloomberg. Available: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-02-09/two-bankers-charged-in-germany-over-swap-sale-to-pforzheim [7 February 2015].

The Six Principles. 2015. [Online]. Principles for Responsible Investment. Available:

http://www.unpri.org/about-pri/the-six-principles/ [14 February 2015].

Stempel, J. 2013. [Online]. JPMorgan in $23 million settlement with clients over Lehman. Reuters.

Available: http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/08/16/us-jpmorgan-lehman-settlement-idUSBRE97F0YJ20130816 [7 February 2015].

Treanor, J. 2014. [Online]. Foreign exchange fines: banks handed £2.6bn in penalties for market

rigging. The Guardian. Available: http://www.theguardian.com/business/2014/nov/12/foreign-exchange-fines-ubs-hsbc-citibank-jp-morgan-rbs-penalties-market-rigging [27 January 2015].

Financial Statements of the Government of New Zealand: For the Year Ended 30 June 2014. 2014.

[Online]. The Treasury. Available: http://www.treasury.govt.nz/government/financialstatements/yearend/jun14/fsgnz-year-jun14-1.pdf [3 February 2015].

Code of Ethics. n.d. [Online]. U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Available:

http://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1217286/000119312511060747/dex99p11.htm [14 February 2015].

Form 10-K. 2003. [Online]. U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Available:

http://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/19617/000095012304002022/y94051e10vk.htm [14 February 2015].

Code of Ethics. 2007. [Online]. U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Available:

http://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/908186/000090818608000032/ex-jpmcodeofethics.htm [13 February 2015].

J.P. Morgan Settles SEC Charges in Jefferson County, Ala. Illegal Payments Scheme. 2009. [Online].

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Available: http://www.sec.gov/news/press/2009/2009-232.htm [13 February 2015].

SEC Charges J.P. Morgan Securities with Fraudulent Bidding Practices Involving Investment of

Municipal Bond Proceeds. 2011. [Online]. U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Available: http://www.sec.gov/news/press/2011/2011-143.htm [13 February 2015].

JPMorgan Chase Agrees to Pay $200 Million and Admits Wrongdoing to Settle SEC Charges. 2013.

[Online]. U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Available: http://www.sec.gov/News/PressRelease/Detail/PressRelease/1370539819965#.VOK4yS4fsxs [7 February 2015].

White, A. 2012. [Online]. PwC fined record £1.4m over JP Morgan audit. The Telegraph. Available:

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/supportservices/8995981/PwC-fined-record-1.4m-over-JP-Morgan-audit.html [16 February 2015].

Wolfsburg Principles. 2015. [Online]. Wolfsburg Principles. Available: http://www.wolfsberg-