Ethics of Tax Breaks on Bank Fines

By Kara Tan Bhala

Banks Are Able to Write Off Fines and Settlements as Tax Deductions

Ostensibly, US government authorities extracted $160 billion from offending banks in fines and legal settlements since the Great Financial Crisis (GFC). This amount is minute compared to the losses incurred by the overall economy. The Dallas Federal Reserve estimates an output loss of $6 trillion to $14 trillion as a result of the crisis. This amounts to $50,000 to $120,000 for every U.S. household, or the equivalent of 40 to 90 percent of one year’s economic output. Indeed, the estimated total fines amount to a mere 1.1 percent of money lost in the U.S. economy. Unjustifiably, the amount gets even smaller, as much as 35% — the corporate tax rate. Banks are able to deduct these fines, levied on them for egregious misconduct, from their tax bills and get away with paying even less.

Settlements and Fines

A June 2016 report from Good Jobs First shows from the beginning of 2010, 26 major U.S. and foreign banks paid out more than $160 billion in penalties levied on them for a range of offenses. The Department of Justice (DOJ) and federal regulatory agencies such as the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), the Federal Reserve and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) brought cases against the banks resulting in fourteen banks accumulating penalties in excess of $1 billion while five of those are in excess of $10 billion. The fourteen banks with total penalties of $1 billion or more since the start of 2010 are as follows:

| Bank of America | $56 billion |

| JP Morgan Chase | $28 billion |

| Citigroup | $15.4 billion |

| Wells Fargo | $10.9 billion |

| BNP Paribas | $10.5 billion |

| Goldman Sachs | $9.1 billion |

| Morgan Stanley | $5.0 billion |

| Deutsche Bank | $4.6 billion |

| HSBC | $4.0 billion |

| Barclays | $3.4 billion |

| UBS | $3.3 billion |

| Credit Suisse | $3.2 billion |

| RBS | $1.9 billion |

| Commerzbank | $1.1 billion |

Source: Good Jobs First

The offenses and egregious misconduct for which these banks were being punished range from selling toxic securities and mortgage abuses to manipulation of foreign exchange and interest rate markets. The following is the category of cases resulting in penalties of at least $100 million.

| Toxic securities and mortgage abuses | $118.4 billion |

| Violations of rules prohibiting business with enemy countries | $15.3 billion |

| Manipulation of foreign exchange markets | $7.4 billion |

| Manipulation of interest rate benchmarks | $5.5 billion |

| Assisting tax evasion | $2.4 billion |

| Credit card abuses | $2.2 billion |

| Failing to report suspicious behavior by Madoff | $2.2 billion |

| Inadequate money-laundering controls | $1.3 billion |

| Discriminatory practices | $0.9 billion |

| Manipulation of energy markets | $0.9 billion |

| Other major cases | $3.8 billion |

Source: Good Jobs First

This list is an astonishing reminder, eight years after the GFC, of the variety of unethical behavior and misconduct in the banking sector. The fines and penalties are presumably meant to deter future bad acts by banks but it is questionable if they achieve this purpose. Banks appear to regard these penalties merely as a cost of doing business. The deterrence and punitive motives for the penalties are even less likely to be achieved when the fines are, shockingly, eligible for tax deductions.

How to Get Your Tax Breaks on Bank Fines

Section 162(f) of the U.S. Tax Code provides that no deduction is allowed under subsection (a) for any fine or similar penalty paid to a government for the violation of any law.

There are two ways offending banks can get tax deductions on fines and penalties levied on their misconduct:

- Corporations are allowed to deduct from their taxable income all ordinary and necessary business expenses. When banks negotiate an out-of-court settlement instead of waiting for a judge to decide the penalty amount, the categorization of the payment as a “fine or penalty” becomes more ambiguous. Banks can claim the vast majority of the payments for legal settlements as “ordinary and necessary cost of doing business” and thus get a tax deduction on those payments. To prevent banks from claiming settlements and fines as a cost of doing business the government agency MUST definitively address the tax status of the penalties.

- In the definition of a fine or similar penalty, the U.S. Tax Code does NOT consider compensatory damages paid to a government as constituting a fine or penalty. This exception is the “tax loophole” a clever tax lawyer can exploit to help banks reduce the amount of money they have to pay to compensate the people harmed by their actions.

A 2005 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report found settlement agreements between corporations and government agencies rarely address tax deductibility.1 This unbelievable oversight by the agencies led to corporations claiming the bulk of settlement payments as tax deductions. Ten years on, the U.S. Public Interest Research Group Education Fund (PIRG) did a follow up study in December 2015. The results show little improvement in ensuring that offending corporations do not deduct from their taxes fines and penalties paid out for misconduct.

The more distinctly agencies specify the tax status of the fines and penalties, the less room there is for banks to make their own interpretation of the amount of the total payment they claim as “fines and penalties”. Agencies that extract the settlements must clearly specify the tax status of the payments to eliminate any possibility for banks’ self-interpretation. In the case of payments that are clearly classified as penalties or fines, tax deductibility would seem highly unlikely, but best practice is to explicitly deny deductions for such payments nonetheless. Without specifying these details in clear, definitive language banks will, without fail, make full use of tax deductions to reduce their punitive bills. The JPMorgan case illustrates this inevitable and morally dubious bank choice.

In November 2013, JPMorgan Chase signed a $13 billion settlement with a number of federal and state enforcement agencies. By agreeing to the penalty, JPMorgan resolved charges of illegally packaging, marketing, selling and issuing residential mortgage backed securities. The DOJ proclaimed the fine as the largest in its history at that time. Unfortunately, the DOJ allowed JPMorgan to classify $11 billion of the costs as legitimate business expense and thus treat the amount as a tax deduction. Effectively the deduction became an almost $4 billion benefit for the bank. The taxpayer is the ultimate loser in this most ethically questionable of tax avoidance moves.

Bank Fines: Their Net Effectiveness

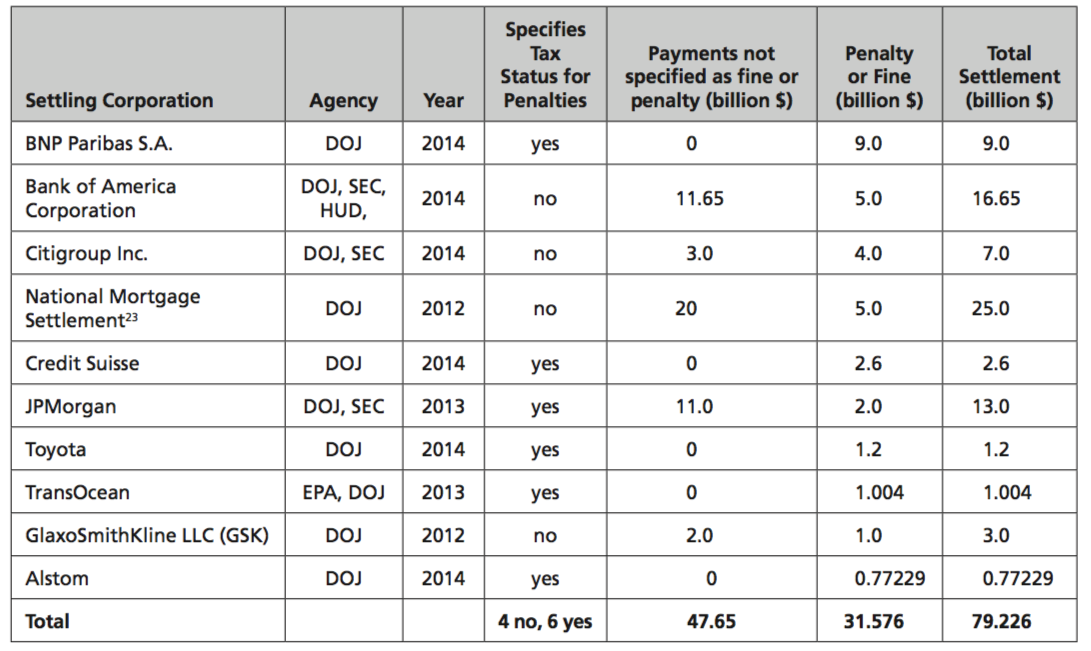

The PIRG Report highlights the ten largest known legal settlements between government agencies and corporations (mainly banks) between 2012 and 2014. The fines were paid in settlement for wrongdoing and totaled over $79 billion. Yet, almost $48 billion of the total was entirely tax deductible. The PIRG Report writes:

As a result of the tax deductibility of these ten settlements, the public will likely forego almost US$17 billion in revenues to the companies accused of wrongdoing. The $48 million that is tax deductible is an estimate. There is no definitive way to know the amount deducted from past settlements because corporations do not have to report specifically how much they have deducted, or what they may deduct in future years. In 2013, the IRS noted that unless an agency explicitly forbids a company from deducting a payment, “almost every defendant/taxpayer deducts the entire amount” as a business expense.

Source: U.S. Public Interest Research Group Education Fund

Source: U.S. Public Interest Research Group Education Fund

These amounts a bank gains through clever tax moves are far too large to ignore and the public has a right to know how much it continues to subsidize the bad behavior of banks.

The CFPB is most vigilant in ensuring bank fines and penalties are not tax deductible. The agency inserts language in the settlements that specifically state fines are non-deductible. The DOJ does not seem particularly concerned to ensure banks do not get tax deductions on fines. The department signs large settlement agreements but between 2012 and 2014, only 18.4 percent of settlement dollars were explicitly non-deductible. Similarly, only 15 percent of fines the SEC negotiates include language to prevent tax deductions.2

The Wells Fargo Bank Case

The recent case of Wells Fargo Bank provides a clear example of tax breaks on bank fines. The bank is able to claim tax deductions on a portion of its $185 million fine.

In September 2016, Wells Fargo & Co. was fined $185 million to resolve claims that bank employees opened deposit, credit-card and debit-card accounts without customers’ approval to meet aggressive sales goals and earn financial rewards. Regulators discovered bank employees secretly opened more than 2 billion accounts that consumers may not have known about.

The regulators involved imposed their respective fines as follows:

- CFPB: $100 million (largest penalty the agency has ever imposed)

- Comptroller of the Currency (OCC): $35 million

- Los Angeles city attorney: $50 million

Of the three settlements only the CFPB in its Consent Order clearly states the fines are not tax-deductible:

“Respondent may not:

a. claim, assert, or apply for a tax deduction, tax credit, or any other tax benefit for any civil money penalty paid under this Consent Order”

The OCC Consent Order does not contain language specifically prohibiting Wells Fargo from claiming tax deductions on its fine.

Neither does the Los Angeles city attorney’s settlement. In its stipulated final judgment, the document labels the $50 million fine on Wells Fargo as civil penalties of which $25 million is paid to the Treasurer of the County of Los Angeles and $25 million goes to the Treasurer of the City of Los Angeles. There appears to be no statement that prohibits Wells Fargo from getting a tax deduction on the penalty.

Therefore, of the total $185 million in fines Wells Fargo pays out, it can conceivably claim tax deductions on $85 million. The bank may effectively get about $30 million back from taxpayers for its bad behavior. This possible outcome hardly seems like justice served.

Ethical Analysis

1. Justice

The penalties and fines these banks pay represent justice obtained by government agencies and the DOJ on behalf of US citizens harmed by bank wrongdoing. The offenses cry out for punishment. Monetary recompense is but a small extent of the full measure of justice the public is owed. The fines and penalties go towards attaining justice in its following forms.

a. Compensatory Justice

Some of the penalties compensate people harmed by a bank’s unethical and illegal acts. Unfortunately, according to U.S. law (see above), compensatory damages paid to a government does not constitute a “fine or penalty” and as such is tax deductible. This loophole means that the government is partially subsidizing bad acts and illegal behavior of banks. This subsidy is another form of bank moral hazard. The bank feels it can misbehave flagrantly because ultimately, the government will be there to help pay its fines, or simply put, bail it out, when the bank is punished and fined.

b. Punitive Justice and Recidivism

The fines and penalties also are supposed to prevent a repetition of the same kinds of misconduct on the part of banks. When banks can deduct large settlements, the deterrent value is seriously undermined. These payments are a form of punishment compelling banks to atone for their wrongdoing. Instead, tax deductions for misconduct penalties encourage banks to the view these payments as simply a cost of doing business. No act is wrong, if it can be paid off, and payments are even tax deductible.

c. Fairness

It is unfair, to say the least, that the public, who is harmed by bank misconduct and for whom justice is sought, ultimately shoulders the burden of the lost revenue when banks write off their settlement penalties. This lost revenue may result in higher taxes or cuts to public programs, bringing further harm to the victims of a bank’s actions.

2. Transparency

Transparency is a crucial basis for ethics. It is a pro-ethical condition that helps or hinders ethical practices. Commutative justice demands transparency. This form of justice belongs in the sphere of transactions and is most relevant to finance and business. It refers to fairness in exchange of goods and services. There must be full informational disclosure between all parties involved in a transaction.

The public remains largely unaware of the tax deductibility of bank settlement agreements. There are no legal standards of transparency that require banks, the DOJ or government agencies to reveal publically the true net value of out of court settlements. The American people surely have a right to know the real public value of the deals signed on their behalf.

-x-

1. United States Government Accountability Office. (2005). Systematic Information Sharing Would Help IRS Determine the Deductibility of Civil Settlement Payments. (GAO Publication No. 05-747)

2. Baxandall, P and Surka, M. Settling for a Lack of Accountability? Which Federal Agencies Allow Companies to Write Off Out-of-Court Settlements as Tax Deductions, and Which Are Transparent about it. U.S. Public Interest Research Group Education Fund, December 2015