The Causes of Economic Inequality

The first in SPI’s series on Inequality

By: May Leung

Difference in income plays a role

One important factor contributing to different levels of wealth is people are paid different wages. There are several reasons why some people are paid millions while some merely earn minimum wage.

(i) Wages are determined by labor market

Wages are a function of the market price of skills required for a job [1]. In a free market, the “market price of a skill” is determined by market demand and market supply. The market price of a skill, and hence the wage for the job that requires the skill, is low if a large number of workers (high supply) are willing and able to offer that skill but only a few employers need it (low demand). On the contrary, when there is low supply but high demand for a skill, the wage for a job requiring the skill goes up.

(ii) Education affects wages

Individuals with different levels of education often earn different wages [2]. This is probably related to reason one: the level of education is often proportional to the level of skill. With a higher level of education, a person often has more advanced skills that few workers are able to offer, justifying a higher wage.

The impact of education on economic inequality is still profound in developed countries and cities [3]. Although there are usually policies of free education in developed nations, levels of education received by each individual still differ, not because of financial ability but innate qualities like intelligence, drive and personal ability. For example, in Hong Kong, 12 years of free education are provided for each citizen, not covering tertiary education, offered only when students receive certain results on public exams.

Moreover, receiving the same level of education does not mean receiving education of the same quality. This accounts for the difference in abilities and hence wages for individuals all receiving, for example, 12 years of education. Therefore, it seems no matter how good the social welfare policy of a country is at preventing denial of education due to financial difficulties, differences in education, in terms of levels and quality, still play a prominent role in economic inequality.

(iii) Growth in technology widens income gap

Growth in technology arguably renders joblessness at all skill levels [3]. For unskilled workers, computers and machinery perform a lot of tasks these workers used to be do. In many jobs, such as packaging and manufacturing, machinery works even more effectively and efficiently. Hence, jobs involving repetitive tasks have largely been eliminated. Skilled workers are not immune to the nightmare of losing jobs. The rapid development in artificial intelligence may ultimately allow computers and robots to perform knowledge-based jobs [3].

The impact of increasing unemployment is stagnant or decreasing wages for most workers, as there is a low demand for but high supply of labor. A small portion of society, usually the owners of capital, controls an ever-increasing fraction of the economy [3]. The income gap between workers who earn by their skills and owners who earn by investing in capital has widened.

Although both skilled and unskilled workers are adversely affected by the technological advance, it seems unskilled workers are subject to worse outcomes [3]. This is because the labor market may still need skilled workers to use computers and operate the advanced machines. The rightward shift in the demand for skilled labor creates an increase in the relative wages of the skilled compared to the unskilled workers. Hence, the income gap among workers also has widened.

(iv) Gender does matter

In many countries, there is a gender income gap in the labor market [3]. For example, in America, the median full-time salary for women is 77 percent of that of men [4]. However, women who work part time make more on average than men who work part-time [4]. Additionally, among people who never marry or have children, women make more than men [4].

It may be difficult to justify such differences. According to a U.S. Census report [4], the wage gap is not fully explained even after accounting for key factors that affect earnings, such as discrimination and the tendency of women to consider factors other than pay when looking for work. The only thing we know for sure is that gender does contribute to a difference in wages in society and hence economic inequality.

(v) Personal factors

It is generally believed that innate abilities play a part in determining the wealth of an individual. Hence, individuals possessing different sets of abilities may have different levels of wealth, leading to economic inequality [3]. For example, more determined individuals may keep improving themselves and striving for better achievements, which justifies a higher wage.

Another example is intelligence [3]. A lot of people believe that smarter people tend to have higher income and hence more wealth. This is debatable. In the book IQ and the Wealth of Nations, Dr. Richard Lynn opined that there is a correlation of 0.82 between average IQ and GDP. However, Stephen Jay Gould, in the book The Mismeasure of Man, criticized it for employing the wrong methods of evaluation.

In addition to innate abilities, diversity of preferences, within a society or among different societies, contributes to the difference in wealth [3]. When it comes to working harder or having fun, equally capable individuals may have totally different priorities, resulting in a difference in their incomes. Their saving patterns may also differ, leading to different levels of accumulated wealth.

Inequality is a vicious cycle

“The rich get richer, the poor get poorer” is not just a cliche. The concept behind it is a theoretical process called “wealth concentration.” Under certain conditions, newly created wealth is concentrated in the possession of already-wealthy individuals [5]. The reason is simple: People who already hold wealth have the resources to invest or to leverage the accumulation of wealth, which creates new wealth. The process of wealth concentration arguably makes economic inequality a vicious cycle.

The effects of wealth concentration may extend to future generations [3]. Children born in a rich family have an economic advantage, because of wealth inherited and possibly education, which may increase their chances of earning a higher income than their peers. These advantages create another round of the vicious cycle.

The French economist Thomas Picketty recently published a book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century [6]. Picketty’s thesis supports the previous proposition. It is a 700-page book on the topic of income inequality. The rich collection of statistics in the book shows that in almost every country (examined by Picketty), the wealth gap has widened since 1980. Picketty holds the view that inequality will remain as long as the aforementioned wealth concentration process persists through generations. However, Picketty argued that global inequality has probably decreased, as there has been rapid growth in Asia partly at the expense of lower-to-middle income earners in developed countries. The statistics show economic inequality is not just the top 10 percent of the population is richer than the bottom 20 percent. Rather, it is “1 percent versus the remaining 99 percent,” i.e. the top 1 percent of the population has the vast majority of wealth in the economy and control of financial markets.

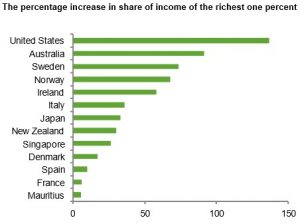

Chart 1

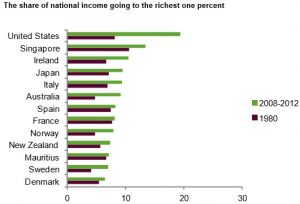

There is both support and criticism for Picketty’s argument inequality has been a persistent phenomenon. World Bank researchers Christoph Lakner and Milanovic Branko agree that inequality in rich countries has been worsening significantly since 1988 [7]. In Oxfam’s Working Paper [8], statistics show that in 24 of 26 countries researched, indeed the richest 1 percent increased their share of income between 1980 and 2012 (see Chart 1). The share of national wealth owned by the wealthiest 1 percent in the U.S. greatly increased after 2008 (see Chart 2), meaning the top 1 percent has captured 95 percent of post-financial crisis growth since 2009, whereas the low-income population became poorer. These statistics further support the proposition in Picketty’s book that inequality is persistent and is getting worse.

Chart 2

Critics of Picketty’s book, such as Michael Hudson, a distinguished research professor of economics at the University of Missouri, mainly focus on the solutions proposed by Picketty [9]. Hudson even supplemented Picketty’s theory in an interview by saying that another reason for the persistence of economic inequality is the top 1 percent exploiting the remaining population and making the latter “in debt” to the former.

It should be noted, however, some sociologists, such as Charles Murray, disagree with the proposition that wealth accumulation is a main cause of economic inequality. They argue factors like innate ability instead of a better starting point are the most important determining factors in the wealth accumulated by a person.

From a broader perspective: Economic policies and structure

(i) Economic neoliberalism

Economic neoliberalism is defined as a form of economic liberalism that supports “free market and minimum barriers to the flow of goods, services and capital” [10]. There are four pillars to this approach, namely capital account liberalization, trade liberalization, domestic liberalization, and privatization [10]. The economy is liberalized in different ways. Countries like the U.S. adopt economic policies promoting neoliberalism (called the “Anglo-American model”) [11].

Advocates of neoliberalism often argue their ideology is helpful in reducing absolute inequality [12]. Some opine neoliberalism itself does not directly generate inequality. Rather, it promotes a free system, which aims to foster economic prosperity. It is the operation of neoliberalism, not the theory itself, which contributes to inequality [13]. Yet, numerous scholars argue that economic neoliberalism is itself a cause of inequality. While it may somehow reduce absolute inequality, it increases relative inequality [12]. According to the economists Howell and Diallo (2007), neoliberal policies in the U.S. led to low wages (30 percent of the working-age population) and inadequate employment (60 percent of the working-age population) [14]. The wealth discrepancy between the rich and the poor, usually the working class, hence widens.

John Schmitt and Ben Zipperer (2006) of the CEPR hold similar views. They claim that economic liberalism, where reduction of business regulations and decline of union membership are inevitable, is a cause of economic inequality [15]. In their analysis of the effects of Anglo-American neoliberal policies, their conclusion is that “the U.S. economic and social model is associated with substantial levels of social exclusion, including high levels of income inequality. At the same time, the available evidence provides little support for the view that U.S.-style labor-market flexibility dramatically improves labor-market outcomes” [15]. So it seems that economic neoliberalism is worsening rather than improving the problem of income inequality.

(ii) Globalization

The great umbrella of globalization, a product of trade liberalization, now covers every corner in the world. The extent of its effects on economic inequality is debatable. Trade economist Paul Krugman supports the proposition that globalization is an important cause of inequality. Because of increasing trade among countries, workers in richer countries face a higher level of competition from those in poorer countries, especially in jobs that do not require a high level of skill. Wages for low-skilled work in richer countries are decline as a result.

Other experts think the effects of globalization on inequality are minor when compared to other causes. For example, Lawrence Katz estimates globalization accounts only for 5 to 15 percent of rising inequality. Robert Lawrence, an economist, disputes any such relationship. Instead, technological innovation causes low-skilled jobs to be replaced by machinery in wealthy nations. Rich nations no longer have significant numbers of low-skilled workers that can be affected by competition from poor nations.

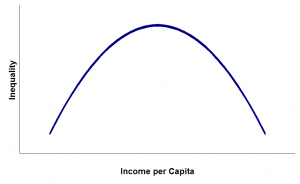

(iii) A Kuznets curve – Phases of development

Nobel laureate economist Simon Kuznets argues that as an economy develops, a natural cycle of economic inequality occurs, represented by an inverted U-shape curve called the Kuznets curve (see Fig. 1). From the curve, we observe as the economy develops, inequality first increases, then decreases after a certain level of average income is attained. In early development, investment opportunities for those who already have wealth multiply so owners of capital can accumulate wealth. At the same time, there is an influx of cheap rural labor to the developing cities, which drives down wages. Therefore, in early development, inequality increases.

Figure 1: Kuznets Curve

When the economy becomes mature, there is democratization and various redistribution mechanisms such as social welfare programs. According to Kuznets, countries move back to a lower level of inequality.

As with any theory, there are criticisms. First, the data set used is said to be prejudiced. Many of the middle-income countries used in Kuznets’ data set are in Latin America, a region with a historically high level of inequality. According to Deininger and Squire (1998), the shape of Kuznets curve tends to disappear after this variable is controlled. Moreover, Kuznets demonstrates his theory by using cross-sectional data. But through using data from large panels of countries, Fields (2001) demonstrates that hypothesis put forward by Kuznets is flawed.

The second criticism is the East Asian miracle (EAM). Basically, EAM describes the rapid economic growth between 1965 and 1990 of eight East Asian countries – South Korea, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore (also known as Four Asian Tigers), Japan, Indonesia, Thailand, and Malaysia. EAM deviates from the Kuznets curve in the sense that the early development economy, particularly manufacturing and exports, grew powerfully, while the population living in absolute poverty decreased, i.e. inequality “surprisingly” decreased.

Many studies have been conducted to identify reasons why the EAM successfully distributes the benefits of rapid economic growth broadly among the population, preventing an initial increase in inequality. Joseph Stiglitz proposed EAM occurred through the immediate reinvestment of initial benefits into land reform increasing the rural productivity and income, as well as universal education and government policies such as increasing wages and limiting price increase in commodities. Hence, there was no significant initial increase in inequality. Average citizens could then have more financial ability to consume and invest in the economy, furthering economic growth. Simply put, what Stiglitz suggests is high economic growth provides resources to promote equality, which then provides positive feedback for growth. This is contrary to the Kuznets curve theory, which insists that economic growth inevitably creates inequality, which then promotes overall growth.

Inequality is not doomed to happen when a country starts developing. If there are sufficient government policies and economic planning, a high growth rate can coexist with low economic inequality at any stage of development.

A free-market society without statutory protection on wages may have unfairly low wages for certain types of work, usually those involving repetitive tasks and low skills, which widens the wealth gap. Likewise, economic neoliberalism, which promotes minimum trade barriers, may also lead to labor exploitation in the form of unfairly low wages. Looking at EAM in a reverse way, if there had not been policies and regulations to distribute the benefits of rapid economic growth broadly among the population, those eight countries might have had totally different fates – economic inequality would have increased in their early stages of development.

Edited by Angela Lutz

REFERENCES

[1] Hazlitt, Henry. Economics in One Lesson. Three Rivers Press, 1988.

[2] Becker, Gary S., and Murphy, Kevin M. The Upside of Income Inequality. The America, 2007.

[3] Causes of Economic Inequality. National Debate Blog. Retrieved on 25 June 2014 at http://nationaldebate2012.blogspot.hk/2012/01/causes-of-economic-inequality.html

[4] U.S. Census Report, 2004. Retrieved on 20 June 2014 at http://www.census.gov/prod/2004pubs/censr-15.pdf

[5] Rugaber, Christopher S., and Boak, Josh. Wealth gap: A guide to what it is, why it matters. AP News, 2014.

[6] Piketty, Thomas. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Harvard University Press, 2014.

[7] Leith van Onselen. Picketty is right about inequality. Unconventional Economist in Global Macro, 2014.

http://www.macrobusiness.com.au/2014/05/picketty-is-right-about-inequality/

[8] Fuentes-Nieva, Ricardo, and Galasso, Nick. Working for the new political capture and economic inequality. 178 Oxfam Briefing Paper – Summary, 2014.

[9] Interview of Michael Hudson: Is Thomas Piketty Right About the Causes of Inequality? Retrieved on 2 July 2014 at http://therealnews.com/t2/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=31&Itemid=74&jumival=11788

[10] World Health Organization. Neo-Liberal Ideas. http://www.who.int/trade/glossary/story067/en/

[11] Portes, Alejandro, and Bryan R. Roberts. The Free-market City: Latin American Urbanization in the Years of the Neoliberal Experiment. Studies in Comparative International Development pp 43–82, 2005.

[12] Smith, Candice. Neoliberalism and inequality: A recipe for interpersonal violence?. Occupy Wall Street. Retrieved on 23 June 2014 at http://occupywallstreet.net/story/neoliberalism-and-inequality-recipe-interpersonal-violence

[13] Smith, C. (2012, Nov 6). Neoliberalism and inequality: A recipe for interpersonal violence?. Retrieved from http://thesocietypages.org/sociologylens/2012/11/06/neoliberalism-and-inequality-a-recipe-for-interpersonal-violence/

[14] Howell, David R. and Mamadou Diallo. Charting U.S. Economic Performance with Alternative Labor Market Indicators: The Importance of Accounting for Job Quality. SCEPA Working Paper, 2007.

[15] Schmitt, John and Ben Zipperer. Is the U.S. a Good Model for Reducing Social Exclusion in Europe? Post-autistic Economics Review 40, 2006.

[16] John Rawls, Political Liberalism: Expanded Edition (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), xli (fn 7).