AI Job Displacements: UBI to the Rescue?

By Chuyuan Sun

According to McKinsey & Company, automation will displace between 400 and 800 million jobs by 2030, based on the midpoint and earliest automation adoption scenario, requiring as many as 375 million people (14% of all workers) to switch occupational categories. For advanced economies, compared to developing economies, the share of the workforce that may need to learn new skills and find work in new occupations is much higher: up to one-third of the 2030 workforce in the United States and Germany, and nearly half in Japan.

Beyond the massive impact, according to the Brookings Institute, another cause of concern is new automation will widen the range of tasks and jobs machines can perform, and potentially affect college graduates and professionals more than in the past. Technological advancements create new jobs, but the transition can be challenging and time-consuming. UBI is a potential solution for the uncertain future of work. By guaranteeing income to all individuals, UBI acts as a safety net, providing stability and easing the hardships of transition. It offers a practical approach to navigate the evolving labor market, enabling individuals to adapt and thrive. Financial assistance implemented amid the COVID-19 pandemic exemplified the feasibility of UBI.

In response to increased levels of unemployment, resulting from Covid 19 many countries introduced financial measurements targeting the problem. The United States provided economic impact payments (stimulus checks) through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) for eligible individuals, and later extended employment assistance with tax waivers through the American Rescue Plan. Besides direct payments and unemployment benefits targeting individuals, governments also included measurements targeting employers. For example, the UK established The Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS) to provide financial support to businesses, aimed at subsidizing wages to prevent mass layoffs. Also, some countries introduced special programs tailored to self-employed and gig workers who may not be eligible for traditional unemployment benefits. The UK’s Self-Employment Income Support Scheme (SEISS) is a pertinent example.

Covid-19 financial payments are probably by far the most far-reaching economic welfare scheme, resembling a universal basic income (UBI). What if a UBI is more feasible than we imagined? Universal Basic Income has long been considered an alternative social security scheme for the existing welfare system yet cost and the financial feasibility are two reasons UBI is seen as impossible and unsustainable. A UBI can alleviate financial stress, and offers a safety net for all. Opponents also argue UBI potentially takes away motivation to work, and may even lead the current state of welfare worsen. Now with experiences drawn from Covid-19 responses, it may be time to reflect on the true feasibility of UBI, reassessing its financial and ethical impacts.

About UBI

The proposal for universal basic income may be traced back to Thomas Paine and Thomas Spencer (King and Marangos 2006). In The Rights of Men, Paine addressed the concept of universal and unconditional basic income for the first time, by proposing cash grants enough to support a decent life for children and the elderly. According to Paine, by “the principle of progress”, no one should be worse off in a state of civilization than they would have been in a state of nature. Therefore, those who have gained from civilization bear the duty to compensate others who have not. Also, Paine proposed the theory of social debt, claiming the wealth accumulated by any individual is largely the effect of society. Thus, the rich have the duty to share their wealth with society.

According to Paine, by “the principle of progress”, no one should be worse off in a state of civilization than they would have been in a state of nature.

Spence deems Paine’s proposal as conservative and unsatisfactory. He proposed money to be equally divided among the rich and the poor. Because land belongs to humankind, there is no moral basis for landed property. Sales and rents should be paid to the people instead of the aristocracy. Spence claimed his proposal had economic, political, and ideological superiority. Given redistribution could abolish poverty and stimulate the market, Spence’s more radical proposal should be more effective than Paine’s. Because government revenue derives from landed property, universal suffrage is inescapable, thus with more citizen involvement in political affairs, citizens have incentive to be watchful, knowing the more saved, the larger their dividends. Ideologically, Spence thought his plan fostered “the spirit of independence” among citizens, ending both the aristocracy and other forms of dependence. Despite Paine’s and Spence’s differences, they embedded proposals of universal basic income in natural rights, although not exclusively.

UBI has evolved since Paine’s and Spence’s time. To discuss the pros and cons of current UBI proposals, it is essential to define what UBI is, especially how it differs from existing welfare programs. According to Fleischer and Hemel (2020), the three main features of UBI are: (1) UBI is unconditional in the sense it is not contingent upon an individual showing deservedness; (2) UBI is delivered via unrestricted cash or cash-like payments; (3) UBI also comes in the form of regularly recurring periodic payments. While UBI distinguishes itself from the existing welfare system for unconditionality, offers cash instead of in-kind benefits, and guarantees a future stream of income, it does share all the above features with negative income tax. In practice, UBI may act the same way as a negative income tax. The framing may affect its political popularity, but the essential features are the same.

According to Malcolm Torry, using the UK as an example, there are four ways to implement a UBI.

1) An income for every UK citizen, large enough to take every household off means-tested benefits (including Working Tax Credits, Child Tax Credits, and Universal Credit), and to ensure that no household with low earned income would suffer a financial loss at the point of implementation. This scheme would be implemented in one go.

2) A “citizen’s income” for every UK citizen, funded from the current tax and benefits system. Current means-tested benefits would be left in place, and each household’s means-tested benefits would be recalculated to consider household members’ citizen’s incomes in the same way as earned income is taken into account. Again, implementation would be in one go.

3) The scheme would start with an increase in Child Benefit. A citizen’s income would then be paid to all 16-year-olds, and they would be allowed to keep it as they grow older, with each cohort of 16-year-olds receiving the same citizen’s income and being allowed to keep it.

4) Inviting volunteers among the pre-retired, between the age of 60 and the state pension age.

The first implementation method, which is also the most traditional view on UBI financing, requires substantial additional public funding, thus may not be feasible in the short term. Torry also argues, if sufficient additional funding were to become available to enable a citizen’s income large enough to float every household off both in-work and out-of-work means-tested benefits, then implementation would not be a problem. The other three should pass all the feasibility tests.

Wage, Job, and Social Protection

Wages are payments that assign monetary value to labor services, also known as the price of labor. In simpler terms and in a general sense, a wage informs one’s ‘worth’ or value. Stemming from Adam Smith, classical economist David Ricardo proposed the theory of value: the value of a good (how much of another good or service it exchanges for in the market) is proportional to how much labor is required to produce it. Human capital theory, developed by economists such as Gary Becker and Theodore Schultz, emphasizes the importance of education and training, suggesting an individual’s productivity and earning potential are positively correlated. Yet, studies have shown individual productivity differences are systemically too small to account for levels of income inequality. Education and training alone cannot determine the productivity or earning potential of an individual. Other factors such as social connections and systemic inequalities can significantly influence opportunities. (Fix 2018)

The critique of the theory points to the signaling and stratifying nature of using wage to define value. Wage levels can influence perceptions of an individual’s value and worth. A higher wage may lead to a perception of higher competence, skill level, education, or experience. This way of reasoning leads to a self-reinforcing cycle where income is used as a measure of productivity, and productivity is used as a justification for income levels. This circular reasoning assumes that individuals with higher income are inherently more productive, while those with lower income are deemed less productive. It does not offer a proper explanation of extreme income disparity, especially when the link between productivity and income is often proved by circular logic, with the lack of an objective matrix to measure the productivity differences among individuals.

Income inequality, stratification, and the assignment of worth are interconnected issues that can be addressed through UBI. By ensuring a basic level of financial security for everyone, UBI challenges the narrow assignment of worth based solely on income, recognizing the inherent value and dignity of all individuals. Implementing UBI promotes a more equitable society, where everyone has the means to thrive and contribute, regardless of their socioeconomic background.

AI Job Displacements

Wage, job, and social protection are interconnected components of the employment landscape. According to the International Labor Organization (ILO), social protection is defined as a “set of policies and programs designed to reduce and prevent poverty, vulnerability and social exclusion throughout the life cycle.” Some of the crucial protections are currently realized through the employer, for example, health insurance and retirement benefits. Beyond practical social protection, affiliation with employers also can bring certain social credits or even recognition to the employed individuals.

Therefore, a potential mass job displacement caused by AI could 1) shake the system’s classifying value and worth, and 2) take away certain means for necessary social protection. With the abrupt absence of both, it could result in panic, intensified by the lack of precautionary measures.

Low-skill occupations are most exposed to robots, middle-skill occupations are most exposed to software, and high-skill occupations are most exposed to AI.

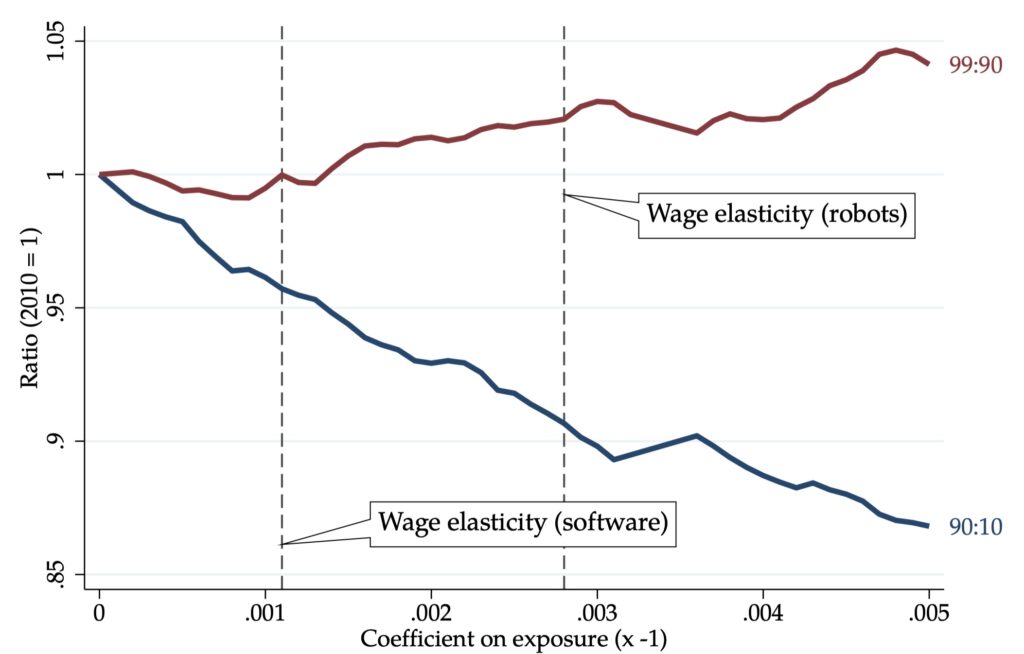

Further computerization and the use of AI will have an extensive impact on labor supply. 60% of occupations, at least one-third of the constituent activities could be automated, implying substantial workplace transformations and changes for all workers. As work gets ‘digitalized’, wages for labor erode. (Frey and Osborne) Workers are likely to reallocate their labor supply to low-skill occupations. This shift has been observed in the US labor market between 1980 to 2005. The reallocation can contribute to income inequality by potentially widening the wage gap between high-skill and low-skill workers. But that does not mean high-skilled workers are safe. Low-skill occupations are most exposed to robots, middle-skill occupations are most exposed to software, and high-skill occupations are most exposed to AI. In fact, as Webb (2020) demonstrates, high-skill occupations are expected to be more exposed to AI, with highly educated and older workers more likely to be affected than any previous technologies. Specifically, the most exposed group to AI is the one consisting of individuals with college degrees or above. To be more precise, referring to AI’s impact on income inequality, Webb presents a perspective that encompasses both increase and decrease in inequality. The result of research shows AI is projected to reduce income inequality by 4% to 9%, measured as the ratio of the 90th to 10th percentile of wages. However, at the top of the distribution, AI is projected to increase inequality measured as the ratio of the 99th to the 90th percentile of wages. In other words, for a majority of workers whose jobs are likely susceptible to technological advancement, the differences of income would be annihilated to a certain degree, yet among the current top earners inequality increases.

The recent development of Large Language Models (LLMs), such as Generative Pretrained Transformers (GPTs), has further impacts on the labor market. Around 80% of the US workforce could have at least 10% of their work tasks affected by the introduction of LLMs, while approximately 19% of the workers may see at least 50% of their work impacted. (Eloundou et al. 2023) The projected effects span all wage levels, with higher-income jobs potentially facing greater exposure to LLMs. The introduction of automation technology has previously been linked to heightened economic disparity and labor disruption, and the study on LLMs underscore the need for societal preparedness to the potential disruption. (Acemoglu and Restrepo 2022)

Ethics Considerations on UBI, Facing the Potential Mass Job Displacement:

From a utilitarian perspective rooted in the recognition of natural rights, the ethical case for UBI in response to AI job displacement becomes even more compelling, particularly when considering the essential link between UBI and social protection.

Natural rights, which encompass inherent entitlements and dignities of individuals, provide a strong foundation for the argument in favor of UBI. Recognizing the fundamental right to a decent standard of living, UBI ensures every person has access to essential resources and social protection, regardless of their employment status. UBI upholds the principle that all individuals deserve a life of dignity and security.

UBI serves as a powerful tool to actualize these natural rights by offering a reliable safety net in the face of AI-induced job displacement. The payment acts as a form of social protection, safeguarding individuals from the detrimental consequences of income loss and financial instability. By providing a guaranteed income to all, UBI ensures people meet their basic needs, maintain their well-being, and have the freedom to pursue a fulfilling life.

UBI helps address social inequalities that may arise from AI-driven job displacement. It reduces the disparities between the privileged and the marginalized, offering an equalizing force that promotes fairness and social justice. By providing financial security to all members of society, UBI embodies the principles of inclusivity and equal opportunity, ensuring that natural rights are upheld and respected. The disruption caused by job displacement, when coupled with sufficient UBI, has the potential to liberate individuals from the worth-assigning system based solely on wage. With UBI providing a reliable income floor, individuals are no longer solely defined by their economic productivity. This liberation allows people to explore diverse pursuits.

One drawback is that UBI in advanced countries, which arguably are the most affected in AI job displacement, would be enormously expensive. According to Hoynes and Rothstein (2019), a sufficient UBI in the context of the US costs nearly double the current total spending of $2.3 trillions on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. Even if UBI is implemented, these current program would still likely be necessary, as each addresses the needs not well served by a uniform cash transfer. It is not possible to finance a UBI through cuts in health care and retirement programs, for a UBI would give a larger share of transfers to the nonelderly and nondisabled than the existing programs. Cutting from those programs will result in the large declines in living standards for the elderly and disabled. Ineffective distribution and insufficient social protection, of course, hurts the overall utility.

From a Kantian ethics perspective, the realization of UBI as an urgent matter is rooted in the recognition of human dignity and autonomy. By considering UBI’s impact on a larger population and their well-being, it becomes an imperative to treat individuals with respect and as ends in themselves. UBI aligns with the moral duty to provide individuals with the means to exercise their autonomy and pursue a dignified life. Embracing UBI in the face of uncertainties related to the established system of assigning value through employment and wage demonstrates a commitment to upholding the inherent worth of individuals, independent of their employment status. It represents a recognition that everyone deserves basic resources and the freedom to pursue their own ends.

UBI offers several unique merits compared to other existing welfare programs, especially in the context of potential mass job displacement caused by AI. Firstly, UBI provides a straightforward and efficient approach towards income support, eliminating complex eligibility criteria, and stigma associated with means-tested programs. Secondly, UBI ensures economic security and stability by acting as an automatic stabilizer during economic downturns and technological disruptions. With a guaranteed income, individuals have a safety net to cover their basic needs, reducing poverty and enhancing overall economic security. Thirdly, UBI empowers individuals by giving them agency and control over their lives, enabling them to pursue education, new careers, or entrepreneurial endeavors. It recognizes diverse paths in response to job displacement, fostering personal growth and innovation. Fourthly, UBI reduces inequality and promotes social cohesion by redistributing resources equitably and ensuring everyone benefits from technological progress. Finally, UBI is flexible and adaptable to changing labor markets, accommodating various forms of work, and supporting individuals in navigating transitions. These unique merits make UBI a compelling policy response to the challenges of AI-driven job displacement, ensuring the well-being and dignity of all individuals.

The potential mass job displacement caused by AI has the capacity to fundamentally disrupt the existing system of assigning value and worth through employment. As automation replaces traditional jobs, individuals may face challenges in finding meaningful work and maintaining a sense of self-worth. In this context, UBI presents an ethical opportunity for reevaluating our societal values. By providing a basic income to all individuals, regardless of their employment status, UBI challenges the notion that one’s worth is determined by their job or income. It recognizes the intrinsic value and dignity of every individual, irrespective of their economic contributions. UBI promotes a shift towards a more equal society, where everyone has the means to live a decent life and pursue their aspirations. It creates a framework that values the well-being and fulfillment of individuals beyond their economic productivity. From an ethical standpoint, UBI offers a transformative vision of social and economic justice, ensuring that no one is left behind in an era of technological advancement and job disruption.

Citations

Acemoglu, Daron, and Pascual Restrepo. “Tasks, Automation, and the Rise in U.S. Wage Inequality.” Econometrica, vol. 90, no. 5, 2022, pp. 1973–2016.

Eloundou, Tyna, et al. “GPTs Are GPTs: An Early Look at the Labor Market Impact Potential of Large Language Models.” 23 Mar. 2023.

Fleischer, Miranda Perry, and Daniel Hemel. “The Architecture of a Basic Income.” The University of Chicago Law Review, 2020.

Fix, Blair. “The Trouble with Human Capital Theory.”

Frey, Carl Benedikt, and Michael A. Osborne. “The Future of Employment: How Susceptible Are Jobs to Computerisation?” Technological Forecasting and Social Change, vol. 114, Jan. 2017, pp. 254–80.

Hoynes, Hilary, and Jesse Rothstein. “Universal Basic Income in the United States and Advanced Countries.” Annual Review of Economics, vol. 11, no. 1, Aug. 2019, pp. 929–58.

King, J. E., and John Marangos. “TWO ARGUMENTS FOR BASIC INCOME: THOMAS PAINE (1737-1809) AND THOMAS SPENCE (1750-1814).” History of Economic Ideas, vol. Vol. 14, 2006, pp. 55–71.

Webb, Michael. “The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on the Labor Market.”