A Sweet Deal? The Ethics of Sugar Taxes

By: Myles Bayliss

On January 1st 2018, the City of Seattle Sweetened Beverage Tax came into effect. The tax is intended to combat obesity and associated healthcare costs. Obesity related diseases place a $147 Billion burden on the US healthcare system as well as a significant burden on medical staff and resources (Zamosky, 2013). This translates to $1250 per household. Whilst not the only cause, excessive intake of added sugars has been implicated in the rise in obesity (Vartanian et al, 2007). Under the tax policy, a standard tax rate of $.0175 per ounce will apply to sweetened beverages. Sweetened beverages are defined as any beverage with added sugar. Drinks such as 100% juices will not be subject to the tax. There is a reduced tax rate for certified manufacturers. That rate is $.01 per ounce.The revenue raised will be used to fund a variety of health- and education-related programs.

Sugar taxes are not a new concept, many other cities and states in the US — including San Francisco, Philadelphia, Portland and Cook County —have either considered or adopted sugar taxes. Sugar taxes are also not unique to the US, nations such as Mexico and Denmark have also instituted sugar taxes. Denmark instituted a sugar tax in the 1930’s. The tax was highly unpopular and was eliminated in 2014 as part of a tax reform policy aimed at boosting the local economy. The tax was criticised as being ineffective in actually curbing sugar consumption as citizens were able to bypass the effects of the tax by travelling to Sweden or Germany to purchase goods such as soda and candy (Stafford, 2012). Mexico instituted a sugar tax in 2014 in response to increasing levels of obesity and associated healthcare costs. Studies show the tax has been effective in reducing soda purchases and consumption, particularly in low-income households (Colchero et al, 2016). Research also projects the taxcould prevent 189,300 new cases of Type 2 diabetes, 20,400 strokes and heart attacks, and 18,900 deaths among adults 35 to 94 years old over a ten-year period as well as potentially yielding savings of $983 million in healthcare costs (Barrientos-Gutierrez, 2018 and Sanchez-Romero et al, 2016).

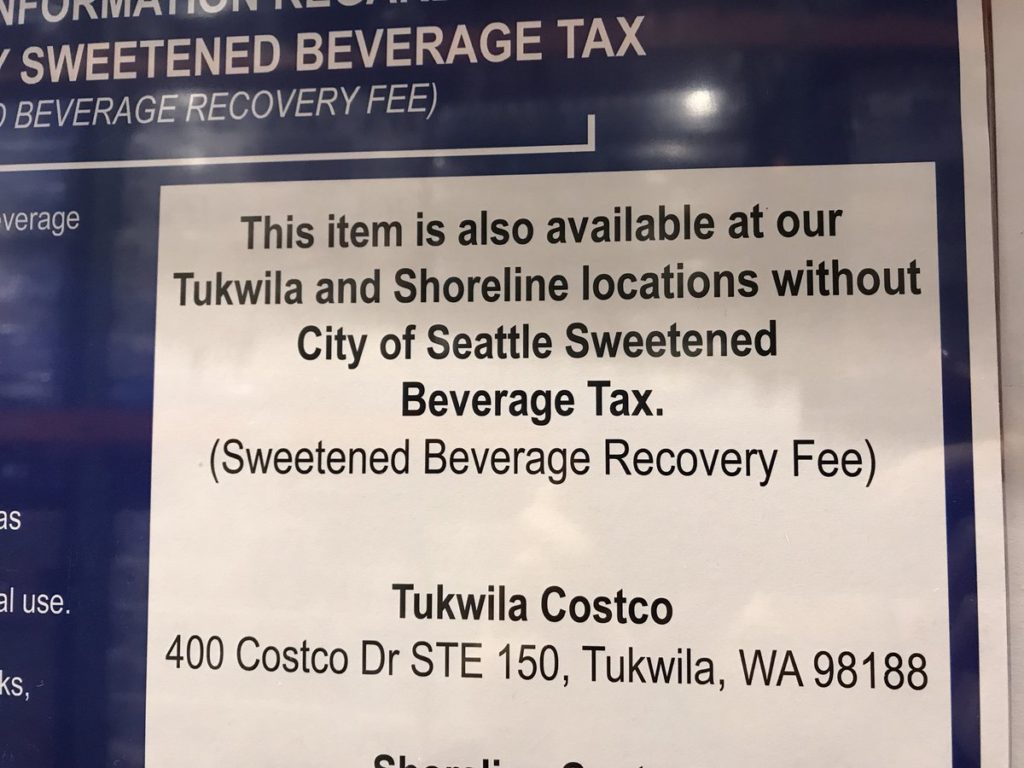

The success of the Mexican sugar tax, as well as the successes of similar taxes on tobacco, is often cited as a justification why a sugar tax would be successful in curbing consumption of soft drinks and thus reducing associated obesity related healthcare costs (Brownell, 2009). Critics of the tax note that, similar to the Denmark sugar tax, consumers are able to bypass the tax by travelling to stores outside the Seattle municipality. Retailers like Costco are helpfully directing shoppers to these locations.

Characterising a Sugar Tax

A sugar tax could fall into two categories; a Pigovian tax, or a sin tax. This section will briefly explain each characterisation before examining how a sugar tax could be categorised.

Pigovian Tax

A Pigovian tax is a tax on any market activity that generates negative externalities (Baumol, 1972). Externalities are costs not included in the market price of a good or service. A Pigovian tax may also be referred to as a corrective tax as a Pigovian tax is intended to correct an inefficient market outcome. The correction is achieved by setting the tax rate at an amount that incorporates social costs of the negative externalities. Essentially a Pigovian tax seeks to reconcile costs associated with a product or activity that is not already incorporated into the cost price – ‘protecting’ innocent bystanders from the actions of others. Using soda as an example, a Pigovian sugar tax would incorporate the potential health care costs associated with the consumption of soda. The attraction of Pigovian taxes is that by nature they are a relatively non-invasive method of remedying market failure and can simultaneously raise revenue a government can use to reduce other taxes (Mankiw, 2009).

Sin Tax

A sin tax is an excise tax (a duty on manufactured goods levied at the moment of manufacture) specifically levied on certain goods deemed harmful to society. In contrast to Pigovian taxes, which are employed to pay for the damage to society caused by these goods, sin taxes are used to increase the price in an effort to reduce their use, or failing that, to increase and find new sources of revenue. Essentially, the purpose of sin taxes is to protect the individual from themselves. On this basis a sin tax may be considered paternalistic in nature (Hoffer, Shugart and Thomas, 2016).

How Should a Sugar Tax be Classified?

The actual characterisation of a sugar tax is difficult. It is arguable to classify a sugar tax as a Pigovian tax due to revenue being used to offset healthcare costs associated with obesity and related diseases. Many medical organizations such as the World Health Organization support this characterization, saying a sugar tax is an example of a Pigovian Tax due to the offset in health care costs as a result of healthier living (World Health Organization, 2016).

Economist Greg Mankiw argues a sugar tax is not a Pigovian tax but a sin tax on the basis that consumption of soft drink does not directly affect ‘bystanders’ like the consumption of gasoline (Mankiw, 2010). Mankiw uses gasoline as an example of a Pigovian tax to demonstrate how a bystander would be impacted. Mankiw argues that an individual who stays in their home drinking soft drinks will not have an impact on others like driving a car would. Driving a car adds to road congestion and air pollution, affecting third parties, adding to their daily commute and respiratory problems. Without a direct external cost, any tax on the product does not actually address an externality and would be just another tax. Based on this argument, it is more accurate to classify a sugar tax as a sin tax as the tax discourages the consumption of sugary beverages. Mankiw also notes that in something of a trade-off, if the average consumer is living a healthier life there may be healthcare costs associated with those ‘added’ years of life (Mankiw, 2006).

Whilst Mankiw makes a fair point that the actual act of soft drink consumption itself has no direct impact on the public at large, there is a strong link between the consumption of soft drink and obesity (Vartanian et al, 2007 and Brownwell, 2009). This link constitutes the externality needed to class a sugar tax as a Pigovian tax. Obesity and related diseases place an undue burden upon the health system which is then borne by others directly because they are unable to access healthcare as readily. Healthcare becomes less accessible due to resources such as beds and staff being occupied, and through increases in healthcare costs and insurance premiums (Leonhardt, 2010). This inaccessibility may be particularly visible in countries with socialised healthcare systems.

Using Mankiw’s example of gasoline, air pollution does not have an immediate effect on a bystander but rather gradually accumulates in damage. Similarly, there will be no immediate impact on a bystander by simply drinking a soda. The negative externality of soda consumption is also an accumulative one. Continual soda consumption leads to obesity or other conditions. A sugar tax that directs any revenue towards healthcare could be classed as a Pigovian tax on this basis. Additionally, a sugar tax increases the price of sugary goods, bringing their costs more inline with the costs of more nutritious food. Obesity costs are not just limited to healthcare. Engineer Sheldon Jacobson of the University of Illinois states that growing obesity rates account for approximately 1 billion additional gallons of gasoline burned by automobiles (Begley, 2012).

Sugar Tax Ethics

Utilitarian Assessment

From a utilitarian perspective, a sugar tax is a fundamentally sound concept. The tax protects both the innocent bystander by not placing the associated healthcare cost burden on her, and the sugar consumer by limiting or discouraging consumption. A reduction in consumption also results in former high sugar eaters living healthier lives. These outcomes confer the greatest benefit to the greatest number without significantly infringing upon or disadvantaging any one specific group (Fitzgerald et al, 2016). A tax is not prohibition and high sugar goods will still be available and accessible. The tax is simply an added layer of protection to the bystander and a way to promote the public interest (Kass, 2014).

From a libertarian perspective, a sugar tax is punitive and infringes upon an individual’s autonomy. According to this perspective, a sugar tax punishes the majority for the actions of the minority. Whilst a Pigouvian tax is conceptually sound, its major flaw is that such a policy assumes each individual is contributing an equal amount of harm (Fleischer, 2015). For example, compare individual A and individual B. A maintains an active lifestyle and only consumes one soda a week. B on the other hand leads a largely sedentary lifestyle and consumes soda and other sugary snacks frequently throughout the week. In this example, A does not contribute as much harm as B does and is highly unlikely to be a direct recipient of the ‘benefits’ of the tax whilst still paying in on a weekly basis.

In sum, the utilitarian position argues that a Pigovian tax maximises the overall good. Discouraging sugar consumption has value for individuals such as improved decision-making and better health. Libertarians argue a sugar tax imposes an undue burden on those who don’t or rarely eat sugar. While it arguably, places some limitation on an individual’s liberty, the tax does not prohibit sugar consumption.

Tax Equity

Critics of sugar taxes argue that sugar taxes are inherently unfair as they place a greater burden upon lower income individuals and households. Factors such as race/ethnicity, family income and educational status are independently associated with intake of added sugars with low income and education groups being particularly vulnerable to eating diets with high added sugars (Thompson, 2009). The general means of determining whether a tax or tax system is fair and equitable is considering horizontal and vertical equity (Gruber 2011). The concept of vertical equity requires people that earn more to pay more tax whilst the concept of horizontal equity requires that persons earning the same should pay the an equal amount of tax.

As noted, lower socio-economic households and individuals are more likely to be have diets high in sugar. Data from the US show that lower income individuals spend on average $4 per person per day to obtain their daily energy intake (Drewnowski and Darman, 2005). In comparison higher earning individuals spend up to $14.27 per day. The proportion of energy coming from sugar is higher in the lowest income groups compared to the higher income groups (Tedstone, 2008). This is due to the greater affordability of food and drink with higher sugar content in comparison to food and drink with greater nutritional value such as fruits and vegetables (Blecher et al 2017).

On this basis a sugar tax is regressive as it may place a greater burden on lower income individuals and households. Such a tax would not achieve vertical equity and cannot be said to be fair in the general measure of tax fairness. Some may argue the tax is not actually regressive as high sugar goods contain little to no nutrition and are not basic necessities (Kass, 2014). Whilst this is an accurate appraisal of sugary foods, the tax would still be regressive in the sense that a greater burden is placed upon low income groups as sugary goods are more affordable. It may also be fair to label the tax as punitive as it punishes lower income groups simply for living within their means. If the tax were to be implemented, tax revenues must be directed to subsidising access to healthier food for low income groups to make up for the sudden inaccessibility of their most affordable food source.

Conclusion

Evidence shows that soda taxes are effective in reducing the consumption of soda under the right circumstances. Any soda or sugar tax must be carefully implemented to avoid accidentally undermining the policy. Whilst highly effective in practice, sugar taxes may have ethical issues that need to be addressed. There is significant tension between the public interest perspective and individual perspective. In addition, there are tax equity considerations.

References Cited

Barrientos-Gutierrez, Tonatiuh, et al. “Correction: Expected Population Weight and Diabetes Impact of the 1-Peso-Per-Litre Tax to Sugar Sweetened Beverages in Mexico.” PLoS One, vol. 13, no. 1, 2018, pp. e0191383.

Baumol, W. “On Taxation and the Control of Externalities.”, American Economic Review, vol. 62, no. 3, 1972.

Begley, Sharon. “As America’s waistline expands, costs soar”, Reuters, 2012.

Blecher, E., et al. “Global Trends in the Affordability of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages, 1990-2016.” Preventing Chronic Disease, vol. 14, 2017.

Bodo, Yann L., Marie-Claude Paquette, and Philippe D. Wals. “Taxing Soda for Public Health. Springer Verlag, DE, 2016.

Brownell, Kelly D., and Thomas R. Frieden. “Ounces of Prevention — the Public Policy Case for Taxes on Sugared Beverages.” The New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 360, no. 18, 2009, pp. 1805-1808.

Colchero, M. A., et al. “Beverage Purchases from Stores in Mexico Under the Excise Tax on Sugar Sweetened Beverages: Observational Study.” Bmj, vol. 352, 2016, pp. h6704.

Drewnowski, Adam, and Nicole Darmon. “The Economics of Obesity: Dietary Energy Density and Energy Cost.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 82, no. 1, 2005, pp. 265S-273S.

Fitzgerald, M. P., Cait P. Lamberton, and Michael F. Walsh. “Will I Pay for Your Pleasure? Consumers’ Perceptions of Negative Externalities and Responses to Pigovian Taxes.” Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, vol. 1, no. 3, 2016.

Fleischer, V. “Curb Your Enthusiasm for Pigovian Taxes.” Vanderbilt Law Review, vol. 68, no. 6, 2015, pp. 1673- 1713.

Gruber, Johnathon. “Public Finance and Public Policy” New York: Worth Publishers, p. 531.

Hoffer, AJ, WF Shughart, and MD Thomas. “Sin Taxes and Sindustry Revenue, Paternalism, and Political Interest.” Independent Review, vol. 19, no. 1, 2014, pp. 47-64

Juul Nielsen, Morten E., and Jørgen D. Jensen. “Sin Taxes, Paternalism, and Justifiability to all: Can Paternalistic Taxes be Justified on a Public Reason‐Sensitive Account?” Journal of Social Philosophy, vol. 47, no. 1, 2016, pp. 55-69.

Kass, Nancy., et al. “Ethics and Obesity Prevention: Ethical Considerations in 3 Approaches to Reducing Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages.” American Journal of Public Health, vol. 104, no. 5, 2014.

Mankiw, N. G. “Smart Taxes: An Open Invitation to Join the Pigou Club.” Eastern Economic Journal, vol. 35, no. 1, 2009, pp. 14-23.

Mankiw, N. G. “Can a Soda Tax Save Us from Ourselves?” The New York Times, 2010, pp. 4.

Mankiw, N, G. “Sin Taxes” Greg Mankiw’s Blog, 2006.

Leonhardt, D. “Greg Mankiw on the Soda Tax” Economix, 2010.

Sanchez-Romero, LM, et al. “Projected Impact of Mexico’s Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Tax Policy on Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease: A Modeling Study.” Plos Medicine, vol. 13, no. 11, 2016.

Sharma, Anurag, et al. “the Effects of Taxing sugar‐sweetened Beverages Across Different Income Groups.” Health Economics, vol. 23, no. 9, 2014.

Stafford, Ned. “Denmark Cancels “Fat Tax” and Shelves “Sugar Tax” because of Threat of Job Losses.” BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), vol. 345, no. nov21 1, 2012, pp. e7889-e7889.

Tedstone, A. “The Low-Income Diet and Nutrition Survey. Findings: Nutritional Science.” Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, vol. 67, no. OCE2, 2008, pp. E91.

Thompson, FE. “Interrelationships of Added Sugars Intake, Socioeconomic Status, and race/ethnicity in Adults in the United States: National Health Interview Survey, 2005.” J Am Diet Assoc, vol. 109, no. 8, 2009, pp. 1376-1383.

Vartanian, Lenny R., Marlene B. Schwartz, and Kelly D. Brownell. “Effects of Soft Drink Consumption on Nutrition and Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” American Journal of Public Health, vol. 97, no. 4, 2007, pp. 667-675.

World Health Organization. “Fiscal Policies for Diet and Prevention of Noncommunicable Diseases.” Technical Meeting Report, Geneva, Switzerland, May 2016.

Zamosky, Lisa. “The Obesity Epidemic. while America Swallows $147 Billion in Obesity-Related Healthcare Costs, Physicians Called on to Confront the Crisis”. vol. 90, Advanstar Communications, Inc, United States, 2013