The Green Climate Fund Lacks Procedural Justice

By Corey O’Dwyer

The Green Climate Fund’s vital role as an agent of distributive justice in the Pacific is impaired by procedural injustices.

This article is part of SPI’s Climate Finance (CliFin) Series.

The Pacific Islands region is home to twenty Pacific Small Island Developing States (PSIDS), all at the forefront of climate-related disasters. In 2020 alone, 71 people perished in climate disasters and economic losses from cyclones. Flooding cost the region close to US$1 billion[1]. As climate disasters become increasingly common and expensive, climate finance will be a vital resource for the Pacific Islands region to develop necessary climate adaptation and resilience measures. Climate finance in the Pacific has been funded more and more by multilateral climate funds, with the largest multilateral climate fund being the most-commonly sought after in the Pacific – the Green Climate Fund (GCF).

The GCF has been a boon to the region, labelled as a “timely saviour”[2] by PSIDS countries when the fund was established in 2010. Since being established, the GCF has invested in 29 climate adaptation and mitigation projects worth US$818 million for Small Island Developing States (SIDS) specifically[3]. However, while the GCF has broadly been an excellent source of climate funding, it comes with considerable issues unique to the Pacific Islands region. In the Pacific, the GCF has:

- been slow to disburse climate finance;

- forced PSIDS countries to compete for climate funding;

- not catered to capacity constraints which are unique to the region;

- failed to support the region in directly accessing climate funding;

- provided much of its climate finance through inefficient and costly means.

This article explores and analyses the successes and shortcomings of the GCF in the Pacific Islands region, and uses ethics analysis to determine how the GCF can enhance its operations in the Pacific, a region in desperate need of improved access to the resources of the GCF.

Achievements of the GCF

Before delving into the myriad of problems unique to the Pacific Islands that the GCF has failed to solve, it is necessary to recount what the GCF has excelled at in the Pacific region. Firstly, the GCF has contributed more to climate finance than any other multilateral climate fund, making it an indispensable source of climate resilience for the region. Secondly, the GCF has been ethical in the way it provides PSIDS countries with climate funding, and through its appropriate prioritisation of investment into climate adaptation projects. Thirdly, the GCF has encouraged PSIDS countries to become regional or national accredited entities, to directly access funding from the GCF.

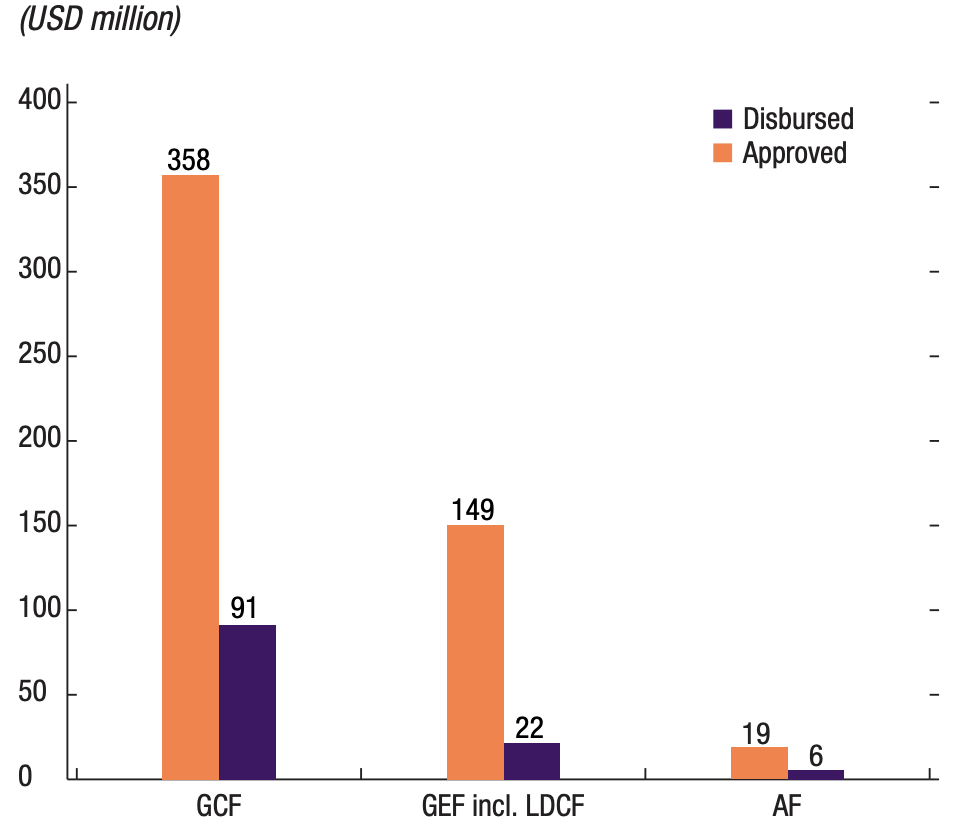

In the Pacific Islands region, funds from multilateral climate channels constitutes 41% of all climate finance, with this amount coming largely from the GCF, Adaptation Fund (AF), Global Environment Facility (GEF), and the Climate Investment Fund[4]. While the AF and GEF have been important funds for the Pacific Islands region, they have recently been overshadowed by the GCF with the introduction of the GCF to the region “markedly increasing” climate finance flows during the 2010s[5]. This is plain to see in Figure 1, which shows how the GCF has invested millions more into the Pacific Islands region since mid-2010 compared with other major climate funds.

Figure 1: Approved and Disbursed Climate Funding by Climate Fund (Source: Unlocking Access to Climate Finance for Pacific Island Countries Report, IMF)

In addition to providing more climate funding than any other multilateral climate fund in the Pacific Islands Region, the GCF also proves itself an ethical climate fund. The GCF avoids giving out climate finance as loans and prioritising climate adaptation projects. It is well-established that climate finance disbursed as loans add significant economic burden on PSIDS countries[6], which the GCF has acknowledged through both words and actions. The GCF’s Independent Evaluation of 2020 states that: “SIDS have received considerably more of their GCF and co-financing via grants […] which is suitable considering […] SIDS’ vulnerability and debt sustainability issues.”[7] An also well-established fact is the Pacific Islands region is among the most-impacted places on earth from climate disasters, and thus climate adaptation funding and projects are vital for the region’s survival. This knowledge too has been recognised by the GCF, and a reason why the GCF has provided more than half of its funding for all SIDS countries towards adaptation projects[8]. These decisions are ethically sound and reflect well the GCF’s aim of being an agent of distributive justice in the realm of climate funds. The GCF’s emphasis on grant-based adaptation projects reflects the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change’s (UNFCCC) concept of ‘restitution’[9]. ‘Restitution’ is outlined in the UNFCCCC’s Fourth Article that climate adaptation is the “responsibility of developed countries” and “should be addressed by them,”[10] which the GCF evidently supports through its actions in the Pacific Islands region.

Finally, the GCF’s encouragement of PSIDS countries and the wider Pacific region to become GCF Accredited Entities stands as a slow growing but important success. GCF Accredited Entities are governmental, non-governmental, public, private, regional or national ‘entities’ which partner directly with the GCF to implement climate projects[11]. This way, governments for example can directly access climate finance instead of going through International Accredited Entities (IAE) like the Asian Development Bank, which can incur fees or lengthen project timelines[12]. Since 2015, the Pacific Islands region has had five entities join as either National Accredited Entities (NAE) or Regional Accredited Entities (RAE)[13], with the most impressive additions being the NAE’s in the Fiji Development Bank (FDB) and the Ministry of Finance and Economic Management Cook Islands (MFEMCI). These developments in accreditation are vastly important for the Pacific Islands region, as regional and national entities can apply their local expertise when developing climate adaptation projects and take responsibility for their own development[14].

Shortcomings of the GCF

The GCF’s role as the leading multilateral climate fund in the Pacific Islands region is paramount, and it has been relatively successful and highly impactful in offsetting the negative impacts of climate change through its work. However, as the GCF has been the leading multilateral climate fund in the Pacific, its shortcomings carry severe consequences for the region. Its successes need to be built upon and its following shortcomings addressed, else the Pacific Islands region will lose a vast array of benefits from accessing this indispensable climate fund. Firstly, the GCF needs to hasten the way it disburses funding in the region. As it currently stands victims of climate disasters do not see climate funding until months – even years – after the event. Secondly, the GCF needs to reconsider the ways in which it divides funding between least developed countries (LDC). PSIDS countries have to compete for funding because the region receives the most amount of climate funding per capita out of all LDCs. This system proffers a deeply flawed way of dividing funds. Thirdly, the GCF needs to cater more to the administrative capacities of PSIDS countries, which are significantly lower than GCF assumptions. Fourthly, the GCF accreditation process needs to be simplified for PSIDS countries. This crucial process is needlessly difficult, long and costly for the countries requiring direct access to climate funds the most. And finally, the GCF needs to reduce the amount that PSIDS countries need to rely on IAEs for their climate funds, as IAEs are less-efficient and more-costly than relying on RAEs or NAEs.

Slow Disbursement of GCF Funding

GCF funding has recently taken an immensely long time to be fully disbursed in the Pacific Islands region. While there are outliers to this rule, the experience of PSIDS countries have largely been the same: slow disbursement due to stringent policies from the GCF prolongs financial aid for far longer than necessary[15]. The GCF has infamously strict policies, fiduciary standards, and safeguards attributable for the lengthy disbursement times[16]. While understandable that GCF authorities strictly adhere to these policies, funding should not take as long as several years before being fully disbursed[17], especially in a region so-often afflicted by climate disasters[18]. As of writing, there are five projects from PSIDS, RAEs, and NAEs either partially completed or about to commence, which have collectively disbursed only 15% of their approved funds, with one of these projects – FP035 – having started as far back as 2015[19]. The GCF has acknowledged their slow disbursement rates with recent improvements to its operational efficiency[20], but these improvements were mostly targeted towards large-scale climate finance projects. The kind of ventures PSIDS countries have seldom received funding for due to the nature of the region[21].

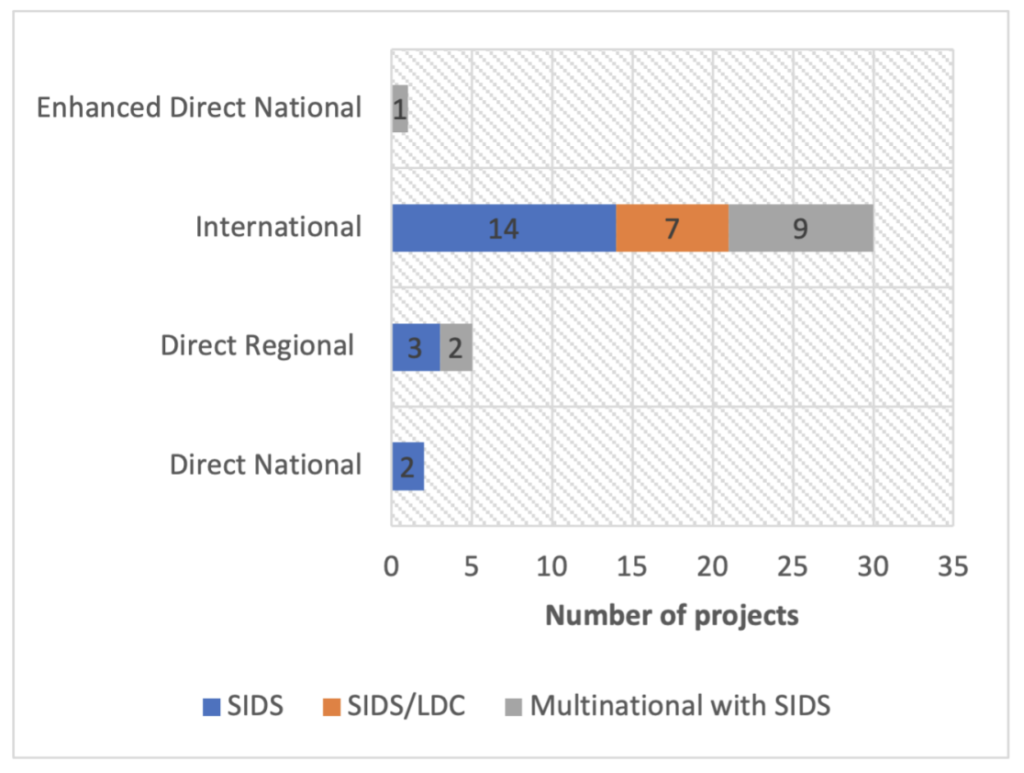

Figure 2: SIDS projects by size categories (Source: SIDS Access to the Green Climate Fund: Understanding the GCF project portfolio in SIDS, Climate Analytics)

If the GCF wants to effectively aid the Pacific Islands region to adapt and develop resilience against more frequent climate disasters, it must prioritise faster disbursement of funding relevant to the region.

Necessitating PSIDS Countries to Compete for GCF Funding

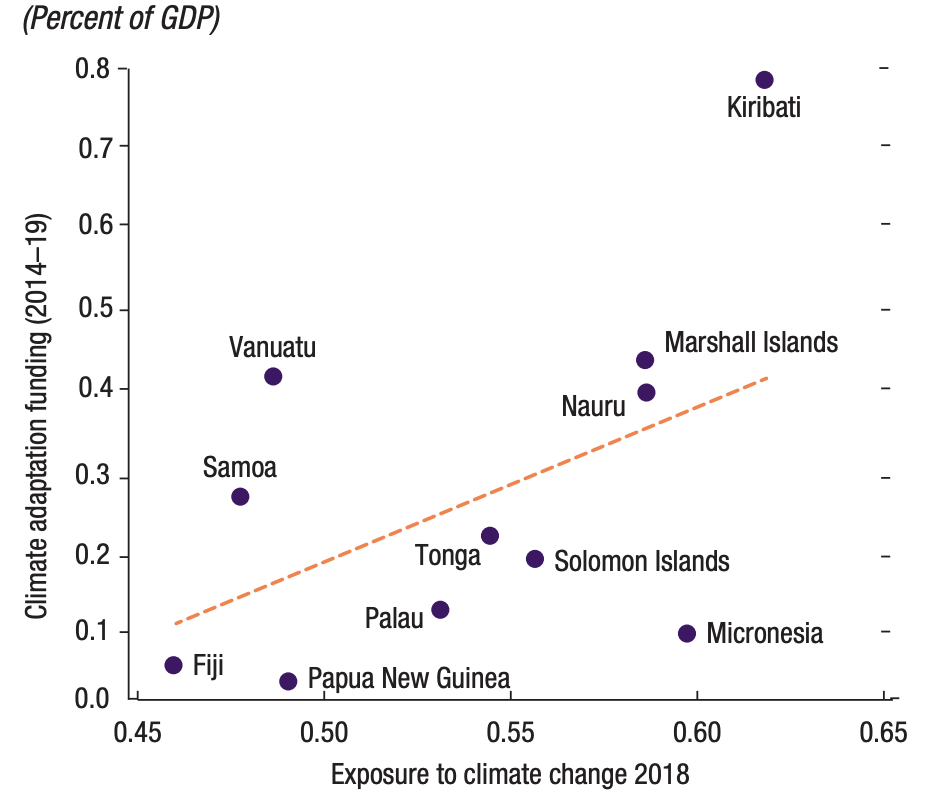

PSIDS countries need to compete with other LDCs for access to GCF funding for two major reasons. Firstly, the GCF has recently been pledged an additional US$9 billion[22]. The availability of funds has prompted LDCs and PSIDS alike to “mobilise significant national resources” to expedite their ability to gain GCF accreditation[23], to have direct access to this new resource. This competition puts PSIDS countries at a disadvantage when vying for additional GCF funds, as PSIDS countries (by virtue of their remoteness and tiny populations) have significantly lower administrative capacity than most other LDCs. Secondly, PSIDS countries are aggregated with the rest of the Asia-Pacific in the GCF. Historically this unfortunate lumping together has heavily skewed data against and drowned out the voices of PSIDS countries[24]. PSIDS countries appeared to be one of the highest recipients of climate funding per capita in 2015, but the reality is that only 4.6% of US$1.3 billion allocated for the Asia-Pacific ended up in the hands of Pacific Island countries[25]. This problem is further exacerbated today because the GCF does not prioritise climate funding by vulnerability[26]. For some PSIDS countries, their needs go unnoticed by the GCF.

Figure 3: Exposure to Climate Change vs Approved Climate Adaptation Funding (Source: Unlocking Access to Climate Finance for Pacific Island Countries Report, IMF)

Therefore, the GCF needs to eliminate the growing trend of PSIDS countries competing with other LDCs for climate funding, by allocating funding by need and vulnerability rather than by application. This solution alone will extinguish the two primary catalysts for fund competition, which PSIDS countries are destined to lose. Similarly, separating the Pacific Islands region from the rest of Asia will greatly reduce the need for PSIDS countries to compete for funding, as the region will not be skewed by climate statistics from Asia.

GCF’s Failure to Account for Capacity Constraints

The GCF has high demands of the administrative capacities of entities trying to access finance from the GCF. While these high demands are perhaps possible to overcome in other LDCs, they are not in PSIDS countries. The region has institutional, structural, and human resource constraints such as population size and geographical location, which are impossible to overcome. These capacity constraints are best seen in how difficult it is for PSIDS countries to apply for and maintain NAE or RAE status with the GCF. The process is innately difficult even without the capacity constraints of a remote PSIDS country. Obtaining direct accreditation entity status with the GCF is a big goal of all PSIDS countries, as the benefits of having direct access to GCF funds is significant. Yet entities from SIDS struggle to even submit the application forms for accreditation, as the burden on human resources is high[27]. For many SIDS entities, there are only five people or less with the skills necessary to work on the application[28]. If these entities manage to overcome the odds and complete the application forms, many become overwhelmed by GCF demands for new or improved policies, extending the process of achieving accreditation by at least one year in high-capacity PSIDS countries[29]. Once an entity has been accepted as a RAE or NAE, they then have to maintain high levels of performance to keep access to GCF funding. This too is difficult for PSIDS countries, and results in inconsistent access to GCF funding[30]. GCF accreditation is quite burdensome on the capacities of PSIDS states, which is reflected in the amount of RAEs and NAEs from the Pacific Islands region. Only 7% of RAEs and NAEs across Africa, Asia-Pacific, Eastern Europe, and Latin America are from the PSIDS countries specifically[31], an underrepresentation compared with especially Asia and Africa. The low representation needs to be a high priority for the GCF to address, as without fixes PSIDS countries will be forced to engage with the GCF through the inferior, costly, and inefficient method of indirect access through IAEs.

The Impossibilities of Direct Access, the Necessity of Direct Access

Becoming a GCF accredited entity is highly desirable for LDCs and PSIDS alike, as direct access to GCF’s climate finance is faster, cheaper, more predictable, and means that ownership is put into the hands of locals, rather than foreign international agents. Yet, despite direct access to the GCF via RAEs and NAEs being objectively superior to indirect access via IAEs, it is needlessly difficult, expensive and time-consuming to become an accredited entity. For PSIDS, it takes on average 1-2 years to achieve NAE status[32] due to accreditation challenges unique to the GCF. These include having the application reviewed by both the GCF Secretariat and the GCF Board[33], notorious for inflating wait times. Applications also cost significant fees, as much as US$25,000 depending on the type of accreditation one applies for[34]. But the process is not over once an entity has achieved accreditation, as they must re-apply for accreditation every five years[35]. This hurdle has raised concerns among some PSIDS leaders that their accreditation might expire before they have managed to develop a project, or that entities will be forced to focus primarily on re-accreditation rather than using the GCF funds for projects[36]. In spite of obstacles, it is well-worth the effort of trying to attain either RAE or NAE status. Direct access to multilateral climate funds like the GCF is associated with greater community engagement, greater efficiency and cheaper projects, as the international middle man is removed[37]. The GCF needs to dismantle the spurious barriers to entry into accredited entity status. The increased ease of access, greater efficiency, and local community engagement constitute vital components to climate change adaptation, and are equally vital to ensuring just, equitable outcomes for PSIDS countries and their people.

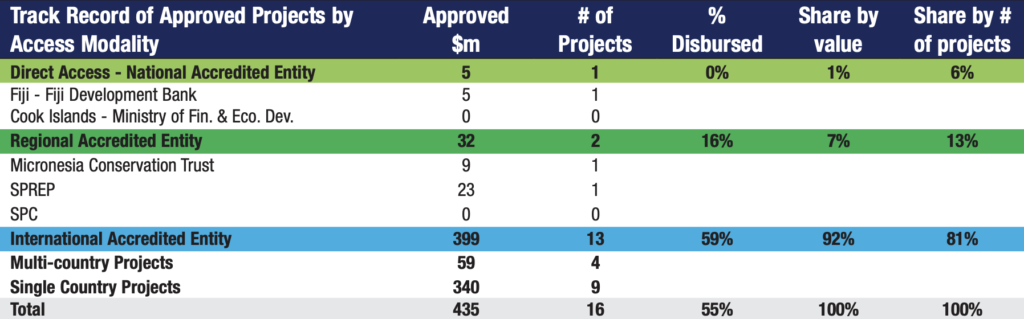

Majority of GCF Projects are Still Through IAEs

Direct access to GCF climate finance is superior to indirect access, but indirect channels of climate finance are still the most common channels used in the Pacific Islands region. This reflects the difficulties associated with applying for accreditation status, and is supported by accounts from the likes of the Samoan Ministry of Finance, which gave up on its accreditation application after it failed to be completed within 5 years[38]. With this in mind, it is unsurprising then the prevalence of IAEs in the Pacific, which account for 92% of the total value of GCF contributions in the Pacific, as seen below in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Record of GCF-Approved Projects in the Pacific through all Modalities (Source: Unlocking Access to Climate Finance for Pacific Island Countries Report, IMF)

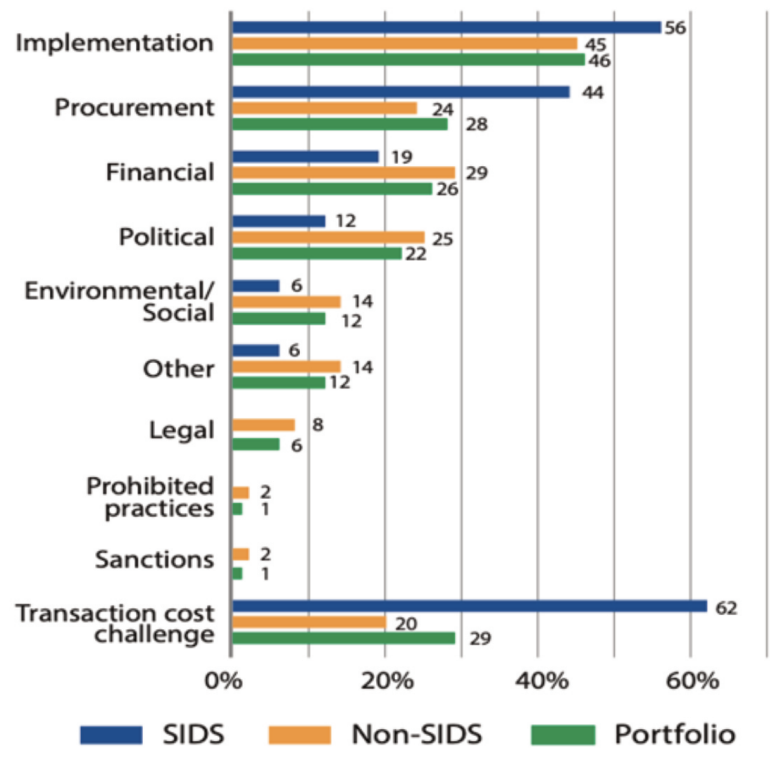

Yet IAEs, unlike DAEs or RAEs, can also be problematic due to the nature of their organisations. The GCF’s 2020 independent review of the effectiveness of GCF investments into SIDS countries found IAEs were disincentivised to work with remote island countries, due to “high transaction costs” and not being perceived as worth the price when working on the small-sized projects associated with SIDS and PSIDS countries[39]. This attitude towards SIDS and PSIDS countries explains high management fees reported by countries seeking GCF finance, as IAEs have been reported to charge around 8 per cent to 20 per cent from the project’s budget[40]. Reluctance from IAEs to work with SIDS and PSIDS countries due to transaction fees is so prevalent, that transaction fees are reported to be the greatest barrier to GCF climate fund disbursement and implementation – which are the responsibilities of IAEs[41].

Figure 5: GCF implementation and disbursement challenges reported by SIDS and non-SIDS [percent of annual performance reports] (Source: Accessing Climate Finance: Challenges and opportunities for Small Island Developing States Report, UN)

The Pacific Islands region needs far greater access to direct channels of climate finance, and the GCF needs to prioritise projects through RAEs and DAEs, whilst deprioritising the use of IAEs that are exploitative or aloof.

Analysis through the Lens of Distributive Justice and Procedural Justice

The GCF’s method of allocating and collecting climate finance makes it an agent of distributive justice. Distributive justice is concerned with the distributions of benefits and burdens, so that “everyone receives their due”[42]. The GCF attempts to enact distributive justice by following the tenets of the ‘polluter pays’ principle, whereby the greatest producers of carbon pollution bear financial responsibility for funding climate adaptation and mitigation projects[43]. As such, the GCF raises much of its funds from high per-capita greenhouse gas (GHG) emitters like Canada, Japan, and Germany, and allocates its funds to LDCs, SIDS and African states in particular[44]. The GCF acts as an agent of distributive justice through: (1) funding climate-resilience projects, (2) limiting and reducing GHG emissions, and (3) accounting for “the needs of nations that are particularly vulnerable to climate change impacts.”[45]

Correctly, the GCF attempts to right the scales of climate injustice according to the tenets of distributive justice. Yet the myriad of problems of the GCF disbursement process impedes effective outcomes in the Pacific Islands region. These problems are procedural injustices and should be rectified if the GCF is to continue being an effective source of climate finance in the Pacific. Procedural justice concerns the fairness of procedures, practices, and agreements between entities[46] and is defined as an individual’s perception of fairness of procedural elements within a social system that regulates allocation of resources[47]. It focuses on the decision-making processes and the interpretation of whether these processes are fair and transparent.

Fairness is the principal tenet of procedural justice, and the concept is at the root of the GCF’s problems in the Pacific Islands region. Perfect procedural justice provides a procedure designed to guarantee that fair outcomes will be achieved. The procedures and practices of the GCF do not ensure PSIDS states get the outcomes desired. Determining what is and is not fair about the GCF in its dealings with PSIDS states is vital for the fund and the region.

Flaws in the funds distribution system and burdensome administrative processes impede the PSIDS states from getting funding. These nations are among the most vulnerable to climate change in the world and their needs are not adequately met, due to procedural injustices demonstrated in the GCF’s conduct within the Pacific Islands region. The GCF’s vital role as an agent of distributive justice in the Pacific is impaired by procedural injustices, which are unfair to and irremediable for PSIDS states. As the largest source of multilateral climate finance in the Pacific, the GCF needs to invest into improving its operations in the region, with measures such as simplifying the direct access accreditation process for SIDS countries, allocating climate finance by vulnerability, and reducing the region’s reliance on IAEs. These improvements are needed, to ensure the GCF becomes a better agent of distributive justice, and for restoring procedural justice to the way the GCF operates in the Pacific Islands region.

Endnotes

[1]“AGENDA ITEM 5: Leveraging Climate Finance Opportunities.” Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, Pacific Islands Forum, 14 July 2021, https://www.forumsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Leveraging-Climate-Finance-Opportunities_Final.pdf.

[2] Samuwai, Jale, and Jeremy Maxwell Hills. “Gazing over the Horizon: Will an Equitable Green Climate Fund Allocation Policy Be Significant for the Pacific Post-2020?” Pacific Journalism Review, vol. 25, no. 1/2, 2019, pp. 158–172., https://doi.org/10.24135/pjr.v25i1.393.

[3] Hook, Scott M. Pacific Climate Change, https://www.pacificclimatechange.net/sites/default/files/documents/Finance%20Mapping%20Revised%20Paper_0.pdf. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

[4] “AGENDA ITEM 5: Leveraging Climate Finance Opportunities.” Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, Pacific Islands Forum, 14 July 2021, https://www.forumsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Leveraging-Climate-Finance-Opportunities_Final.pdf.

[5] United Nations Development Programme, 2021, Climate Finance Effectiveness in the Pacific: Are We on the Right Track? , https://www.undp.org/pacific/publications/climate-finance-effectiveness-pacific-are-we-right-track-discussion-paper. Accessed 8 Apr. 2023.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Chase, Vasantha, et al. GCF Independent Evaluation Unit, 2020, Independent Evaluation of the Relevance and Effectiveness of the Green Climate Fund’s Investments in Small Island Developing States , https://ieu.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/230330-sids-final-report-top-web-isbn.pdf. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Samuwai, Jale, and Jeremy Maxwell Hills. “Gazing over the Horizon: Will an Equitable Green Climate Fund Allocation Policy Be Significant for the Pacific Post-2020?” Pacific Journalism Review, vol. 25, no. 1/2, 2019, pp. 158–172., https://doi.org/10.24135/pjr.v25i1.393.

[10] Hook, Scott M. Pacific Climate Change, https://www.pacificclimatechange.net/sites/default/files/documents/Finance%20Mapping%20Revised%20Paper_0.pdf. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

[11] Green Climate Fund. “Green Climate Fund: Partners.” Green Climate Fund, Green Climate Fund, https://www.greenclimate.fund/about/partners/ae.

[12] Hook, Scott M. Pacific Climate Change, Pacific Experiences on Working on Accreditation for the Green Climate Fund and the Adaptation Fund., https://www.pacificclimatechange.net/document/pacific-experiences-working-accreditation-green-climate-fund-and-adaptation-fund. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

[13] United Nations Development Programme, 2021, Climate Finance Effectiveness in the Pacific: Are We on the Right Track? , https://www.undp.org/pacific/publications/climate-finance-effectiveness-pacific-are-we-right-track-discussion-paper. Accessed 8 Apr. 2023.

[14] Ibid.

[15] “AGENDA ITEM 5: Leveraging Climate Finance Opportunities.” Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, Pacific Islands Forum, 14 July 2021, https://www.forumsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Leveraging-Climate-Finance-Opportunities_Final.pdf.

[16] Fouad, Manal, et al. International Monetary Fund, 2021, Unlocking Access to Climate Finance for Pacific Island Countries, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Departmental-Papers-Policy-Papers/Issues/2021/09/23/Unlocking-Access-to-Climate-Finance-for-Pacific-Islands-Countries-464709. Accessed 29 Mar. 2023.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Chase, Vasantha, et al. GCF Independent Evaluation Unit, 2020, Independent Evaluation of the Relevance and Effectiveness of the Green Climate Fund’s Investments in Small Island Developing States , https://ieu.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/230330-sids-final-report-top-web-isbn.pdf. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

[19] Green Climate Fund. “FP035: Climate Information Services for Resilient Development Planning in Vanuatu.” Green Climate Fund, Green Climate Fund, 15 Dec. 2016, https://www.greenclimate.fund/project/fp035.

[20] “GCF: Catalysing Finance for Climate Solutions.” Green Climate Fund, Green Climate Fund, 2023, https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/230310-catalysing-finance-climate-solutions-web.pdf.

[21] Qui, Kristin, et al. Climate Analytics, 2021, SIDS Access to the Green Climate Fund: Understanding the GCF Project Portfolio in SIDS, https://climateanalytics.org/media/sids_access_to_the_green_climate_fund_1.pdf. Accessed 27 Apr. 2023.

[22] Green Climate Fund. “Countries Step up Ambition: Landmark Boost to Coffers of the World’s Largest Climate Fund.” Green Climate Fund, Green Climate Fund, 24 Oct. 2019, https://www.greenclimate.fund/news/countries-step-ambition-landmark-boost-coffers-world-s-largest-climate-fund.

[23] Samuwai, Jale, and Jeremy Maxwell Hills. “Gazing over the Horizon: Will an Equitable Green Climate Fund Allocation Policy Be Significant for the Pacific Post-2020?” Pacific Journalism Review, vol. 25, no. 1/2, 2019, pp. 158–172., https://doi.org/10.24135/pjr.v25i1.393.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Hook, Scott M. Pacific Climate Change, https://www.pacificclimatechange.net/sites/default/files/documents/Finance%20Mapping%20Revised%20Paper_0.pdf. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

[27] Chase, Vasantha, et al. GCF Independent Evaluation Unit, 2020, Independent Evaluation of the Relevance and Effectiveness of the Green Climate Fund’s Investments in Small Island Developing States , https://ieu.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/230330-sids-final-report-top-web-isbn.pdf. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Fouad, Manal, et al. International Monetary Fund, 2021, Unlocking Access to Climate Finance for Pacific Island Countries, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Departmental-Papers-Policy-Papers/Issues/2021/09/23/Unlocking-Access-to-Climate-Finance-for-Pacific-Islands-Countries-464709. Accessed 29 Mar. 2023.

[30] “AGENDA ITEM 5: Leveraging Climate Finance Opportunities.” Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, Pacific Islands Forum, 14 July 2021, https://www.forumsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Leveraging-Climate-Finance-Opportunities_Final.pdf.

[31] Green Climate Fund. “Accredited Entities.” Green Climate Fund, Green Climate Fund, 27 Feb. 2023, https://www.greenclimate.fund/about/partners/ae?f%5B%5D=field_subtype%3A227.

[32] “AGENDA ITEM 5: Leveraging Climate Finance Opportunities.” Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, Pacific Islands Forum, 14 July 2021, https://www.forumsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Leveraging-Climate-Finance-Opportunities_Final.pdf.

[33] Hook, Scott M. Pacific Climate Change, https://www.pacificclimatechange.net/sites/default/files/documents/Finance%20Mapping%20Revised%20Paper_0.pdf. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

[34] Fouad, Manal, et al. International Monetary Fund, 2021, Unlocking Access to Climate Finance for Pacific Island Countries, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Departmental-Papers-Policy-Papers/Issues/2021/09/23/Unlocking-Access-to-Climate-Finance-for-Pacific-Islands-Countries-464709. Accessed 29 Mar. 2023.

[35] Liagre , Ludwig, and Laura Atondeh. ASEAN, 2021, The Process of GCF Accreditation for National and Regional Entities: What Are Some of the Opportunities in the ASEAN Region? , https://asean-crn.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Information-Note-Climate-Finance-GCF-Opportunities-in-ASEAN.pdf. Accessed 8 Apr. 2023.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Hook, Scott M. Pacific Climate Change, Pacific Experiences on Working on Accreditation for the Green Climate Fund and the Adaptation Fund., https://www.pacificclimatechange.net/document/pacific-experiences-working-accreditation-green-climate-fund-and-adaptation-fund. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

[38] Fouad, Manal, et al. International Monetary Fund, 2021, Unlocking Access to Climate Finance for Pacific Island Countries, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Departmental-Papers-Policy-Papers/Issues/2021/09/23/Unlocking-Access-to-Climate-Finance-for-Pacific-Islands-Countries-464709. Accessed 29 Mar. 2023.

[39] Chase, Vasantha, et al. GCF Independent Evaluation Unit, 2020, Independent Evaluation of the Relevance and Effectiveness of the Green Climate Fund’s Investments in Small Island Developing States , https://ieu.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/230330-sids-final-report-top-web-isbn.pdf. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

[40] Samuwai, Jale, and Jeremy Maxwell Hills. “Gazing over the Horizon: Will an Equitable Green Climate Fund Allocation Policy Be Significant for the Pacific Post-2020?” Pacific Journalism Review, vol. 25, no. 1/2, 2019, pp. 158–172., https://doi.org/10.24135/pjr.v25i1.393.

[41] De Marez, Laetitia, et al. United Nations, Accessing Climate Finance: Challenges and Opportunities for Small Island Developing States, https://www.un.org/ohrlls/sites/www.un.org.ohrlls/files/accessing_climate_finance_challenges_sids_report.pdf. Accessed 24 Apr. 2023.

[42] “Did Perpetrators of Financial Crisis 2008 Get Justice They Deserved?” Seven Pillars Institute, 23 May 2013, https://sevenpillarsinstitute.org/financial-crises-perpetrators-and-justice/.

[43] “What Is the Polluter Pays Principle?” Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, 23 Sept. 2022, https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/explainers/what-is-the-polluter-pays-principle/.

[44] “Resource Mobilisation: GCF-1.” Green Climate Fund, Green Climate Fund, 22 Aug. 2022, https://www.greenclimate.fund/about/resource-mobilisation/gcf-1.

[45] “Green Climate Fund.” United Nations, https://un-rok.org/about-un/offices/gcf/.

[46] “Did Perpetrators of Financial Crisis 2008 Get Justice They Deserved?” Seven Pillars Institute, 23 May 2013, https://sevenpillarsinstitute.org/financial-crises-perpetrators-and-justice/.

[47] Mulgund, Shrusti. “Importance of Distributive Justice, Procedural Justice and Fairness in Workplace.” International Journal of Management and Humanities, vol 25, issue 6, January 2022, p1.