The Ethics of Minimum Wage Legislation

The fifth in SPI’s Inequality Series

AN OVERVIEW OF MINIMUM WAGE LEGISLATION

Minimum wage legislation is hotly debated. A minimum wage is the lowest hourly, daily or monthly remuneration employers legally have to pay to workers. The main purpose of the legislation is to ensure employers, who usually have higher bargaining power in the labor market, do not exploit their workers and that workers earn a fair living wage.

Apart from doing good to labor, proponents of the minimum wage legislation also argue the legislation can benefit the employers as well. According to Filene (1923), an increase in the wages of the lowest paid workers has, in general, a positive effect on their work ethic, their abilities and willingness to acquire skills, and their overall level of job performance [1]. Some employers may think minimum wage is not necessary, as they are paying a decent wage to their workers and hence their workers will have good work ethic and level of performance even without the legislation of minimum wage. These employers may think they are unaffected by those in their industry who pay an unsatisfactorily low wage. This belief is untrue. A mere subset of employers paying below-subsistence wages will drag down the quality of the labor in a whole sector, as workers are a common resource available to all businesses in a given location or industry [1]. Prasch (1998) opines that the solution to this “problem of the commons” is to set minimum wages for every employer in a given region or industry [2].

Another benefit brought to employers by legislation, according to the proponents of legislated minimum wage, is the higher incentive to improve their management and innovation. The proponents claim that in the presence of a minimum wage, firms would have a direct incentive to modify their management strategies, adopt new techniques of production, and invest in their secondary labor market workers [3].

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN LEGISLATED MINIMUM WAGE AND THE LEVEL OF EMPLOYMENT

The Opponents’ View

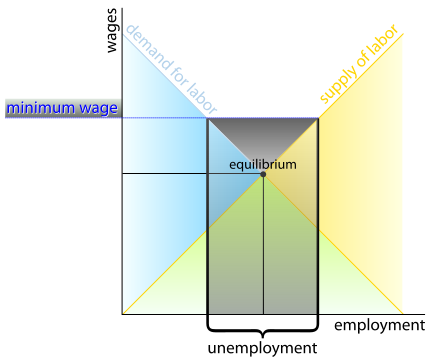

Opponents of the minimum wage legislation often claim the legislation is subject to the perversity thesis. This means the legislation is a well-intentioned policy, but it inadvertently harms the very group of people it aims to protect: the workers [4]. The rationale behind, as claimed by the opponents, can be deduced from the basic textbook demand-and-supply model. In a free market without any legislated minimum wage, the workers are paid the equilibrium wage. As an effective minimum wage must be above the equilibrium wage for labor, the setting of minimum wage will lead to excess supply of labor (see Fig.1). Hence, under this model, increased levels of unemployment, especially among those workers with lower skills and knowledge, will result [5]. Under this model, the imposition of minimum wage has a very limited impact on the higher skill labor market as the equilibrium wage is usually very high and the minimum wage has to be set at a very high level to make a difference in employment [6]. Therefore, the opponents argue the minimum wage legislation does help a portion of workers by increasing their wages, but will at the same time harm a lot of them as they may lose their jobs.

Figure 1: Equilibrium Wage vs. Minimum Wage

The Proponents’ View

By contrast, supporters of minimum wage legislation hold the labor market cannot be simply treated as another market for a commodity [7]. The above basic textbook demand-and-supply theory alone is insufficient to account for the complicated labor market. Proponents of the minimum wage legislation argue the basic approach overlooks an important aspect of the reality: the impact of the increased consumption out of wage incomes due to the higher wages. The proponents argue the legislated minimum wage induces an increase in the marginal propensity to consume (MPC) for society as a whole, and hence increases the level of employment.

With minimum wage legislation, the wages for some jobs, especially those requiring low levels of skills and knowledge, increase. The level of consumption out of profits declines, as the firms face a higher operational cost. The level of consumption out of wage incomes, however, rises, as the workers have a higher spending capacity with the higher wages. The rate of consumption out of profits is lower than that out of wage incomes [8]. It means that although the firms will consume less, the workers will consume more, and the overall effect is the whole society will consume more. This redistribution of money from profits to wage incomes leads to an increase in MPC for society as a whole [9].

With a higher MPC, one extra dollar will generate a higher level of consumption in the whole society. There will be higher levels of investment [10]. Demand for labor increases as a result, increasing the overall level of employment.

Nevertheless, there is an upper boundary to such an increase in the employment level under this theory. The rise in the level of wages due to the setting of minimum wage should not be so high that it would seriously inhibit the firms’ desire to invest [11].

Empirical studies

Results of empirical studies towards the relationship between minimum wage legislation and level of employment are inconsistent. Some studies show there is no relationship between the two. For example, Card and Krueger (1995) studied the 1992 increase in New Jersey’s minimum wage and several other increases, and concluded the negative employment effects of legislated minimum wage are minimal or none [12]. This conclusion holds in labor market for unskilled workers as well [12]. Later in 2000, Card and Krueger reanalyzed earlier studies with updated data, and reached a conclusion that general speaking, the older results of a negative employment effect of the legislation of minimum wage did not hold in the long run with more data [13].

Moreover, three economists, Dube, Lester and Reich (2010), applied the methodology used by Card and Krueger and reached similar results as Card and Krueger. They analyzed employment trends for several categories of low-wage workers from 1990 to 2006, and found that increase in minimum wages had no negative effects on low-wage employment [14].

However, a 2011 study by Baskaya and Rubinstein of Brown University find that at the federal level increases in minimum wage have an instantaneous negative impact on employment, especially among teenagers [15]. Labor economists, Fang and Lin (2013), studied minimum wage and employment in China, and reached the conclusion that minimum wage had adverse effects on employment in the Eastern and Central regions of China [16].

Maybe a more neutral and balanced view is from The Economist (2013). The publication claims a moderate minimum wage can “boost pay with no ill effects on jobs” [17]. An example is the federal minimum wage in U.S, which is set at 38% of median income. Some studies find that federal minimum wages have no adverse impact on employment, whereas others find that there is just a small impact. However, high minimum wages are found to hit employment, according to The Economist [17]. An example is the minimum wage in France, which is set at more than 60% of the median for adults. The youth unemployment rate in France is abnormally high. In 2013, 26% of 15- to 24-year-olds were not employed.

CAN JUSTICE BE ACHIEVED BY LEGISLATING FOR MINIMUM WAGE?

We look at the concept of “justice” by adopting the widely-accepted definition proposed by Aristotle. Aristotle says that justice is proportional: each person is given his or her due. The model of distributive justice is the focus here, as this is the most relevant type of justice in the present discussion, compared to the others like compensatory justice and corrective justice.

Distributive justice is achieved when there is fair distribution of benefits and burdens by the state, so that everyone receives their due. In determining whether the distribution is “fair” and what a person’s “due” is, observe the five types of distributive norms defined by Forsyth: equity, equality, power, need and responsibility [18]. Members of a large group prefer to base allocation of benefits and burdens on equity, and hence this will be the distributive norm adopted in here. The distribution is fair, and a person receives his or her due, when what the individual receives is proportional to his or her input.

Legislated minimum wage can achieve distributive justice, as the workers receive what they are worth, and the community does not have to bear the burden that it does not generate.

First, consider the labor side. Without minimum wage, workers, especially those who are unskilled and engaged in repetitive tasks, do not receive benefits (wages) proportional to their contribution (labor work). There are two major reasons for this outcome.

First, in real labor market, there is usually a monopsony. The economics profession, including those who are against minimum wage legislation, generally agree that a large dominant employer in a region can offer lower wages that would result from a perfectly competitive labor market [19].

Secondly, there are concerns about the unequal bargaining power of the employers and the labor. There is always unemployment in every society, particularly in the sectors that require low skills and knowledge. The unemployed are receiving, by definition, a wage of zero [19]. The wage that is acceptable to the most desperate potential worker becomes the market wage [19]. Therefore, employers generally have a higher bargaining power than labor [20]. In light of these circumstances, the “invisible hand” cannot guarantee that every worker obtains a wage reflecting his or her level of productivity [21].

Hence, arguably, minimum wage legislation can improve the above adverse situations faced by workers by helping them to obtain wages more consistent with the efforts they put in their work.

We now turn to the point that minimum wages can alleviate the burden of production cost possibly shifted from the firms to the whole community. Kapp, K.W. (1950) argues that workers face “overhead costs” like companies do [22]. Workers have to cover the cost of the maintenance of themselves and their families, whether or not they are employed or earning sufficient wages. If their wages are unjustifiably low and hence insufficient to cover their “overhead costs”, these costs must be covered by their families, or more probably, the whole community. Exploitation by employers through paying unfair wages to workers can effectively transfer a portion of the production costs, which should be born by the employers themselves, to the larger community. Following this logic, the burden is not fairly distributed among different parties in society, as what should be shouldered by firms is shifted to society. With minimum wage (set at a optimum level which allows the workers to support their living), the cost of production is not spread among the whole community.

To conclude, minimum wage legislation can achieve distributive justice, as a proper minimum wage can ensure that workers, especially those working in jobs requiring low levels of skill and knowledge, get what they deserve according to their input in their jobs. The community will not have to share the production cost which should be borne by the firms in terms of paying sufficient wages.

REFERENCES

[1] Filene, E. A. (1923). The Minimum Wage and Efficiency. American Economic Review 13, pp. 411-415.

[2] Prasch, R. E. (1998). American Economists and Minimum Wage Legislation During the Progressive Era: 1912-1923. Journal of the History of Economic Thought 20(2), pp. 161-175.

[3] Prasch, R. E. (1996). In Defense of the Minimum Wage. Journal of Economic Issues 30(2), pp. 391-397.

[4] Hirschman, A. O. (1991). The Rhetoric of Reaction. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press.

[5] Gwartney, J. D., Stroup, R. L., Sobel, R. S., & Macpherson, D. A. (2003). Economics: Private and Public Choice (10th ed.). Thomson South-Western, p. 97.

[6] Mankiw, N. Gregory. (2011). Principles of Macroeconomics (6th ed.). South-Western Pub, p. 311.

[7] Prasch, R. E., & Sheth, F. A. (1999). The Economics and Ethics of Minimum Wage Legislation. Review of Social Economy Vol LVII No.4.

[8] Kalecki, M. (1971). Selected Essays in the Dynamics of the Capitalist Economy. Cam- bridge: Cambridge University Press.

[9] Ibid at [7].

[10] Fazzari, S., & Mott, T. (1986-87). The Investment Theories of Kalecki and Keynes: An Empirical Study of Firm Data, 1970-1982. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 9(2), pp. 171-187.

[11] Ibid at [7].

[12] Card, D., & Krueger, A. (1995). Myth and Measurement: The New Economics of the Minimum Wage.

[13] Card, D.,& Krueger, A. (2000). Minimum Wages and Employment: A Case Study of the Fast-Food Industry in New Jersey and Pennsylvania: Reply. American Economic Review, Volume 90 No. 5, pp. 1397-1420.

[14] Dube, A., Lester, T. William, & Reich, M. (2010). Minimum Wage Effects Across State Borders: Estimates Using Contiguous Counties. The Review of Economics and Statistics 92 (4), pp. 945–64.

[15] Yusuf Soner Baskaya, & Yona Rubinstein. (2011) Using Federal Minimum Wages to Identify the Impact of Minimum Wages on Employment and Earnings Across the U.S. States.

[16] Fang, T., & Lin, C. (2013). Minimum Wages and Employment in China. Retrieved from http://ideas.repec.org/p/iza/izadps/dp7813.html on 25 Jul 2014.

[17] Minimum Wages, The Logical Floor. (2013). The Economist.

[18] Forsyth, D. R. (2006). Conflict. In Forsyth, D. R., Group Dynamics (5th Ed.). Belmont: CA, Wadsworth, Cengage Learning, pp. 388-389.

[19] Ibid at [7].

[20] Smith, A. (1937). An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. New York: Modern Library.

[21] Prasch, R. E. (1999). John Bates Clark’s Defense of Minimum Wage Legislation. Paper presented to the annual meetings of the History of Economics Society, Greensboro, NC. June.

[22] Kapp, K. W. (1950). The Social Costs of Private Enterprise. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press.