Applying Utilitarianism: Are Insider Trading and the Bailout of GM Ethical?

Consequentialism

- Definition

Consequentialism is a normative ethical theory, which means, it is a theory about ethical action and a proposed method for deciding how one should choose the right ethical act. (Feiser) Consequentialism says that the consequences of an action are all that matter when taking an ethical decision to act. There is important reason for the root word. The word consequence is selected carefully and it is possible to make a distinction between the word itself and synonyms such as, results or outcomes. (Haynes) The word result or outcome is more commonly understood to mean the product of an action directly and inevitably follows from that action. Consequences have the possibility of being probable, or hypothetical. Alternative moral theories to consequentialism are: deontology, which proposes that ethical decisions should be made by following rules or fulfilling duties; and virtue ethics, which proposes that the ethical action to be taken is the one that would be taken by a virtuous person.

Consequentialist theories have been around for a long time. But the term “consequentialism” was coined by Elizabeth Anscombe in her essay “Modern Moral Philosophy” in 1958. (Frost) Utilitarianism is by far the most widely known form of consequentialism, and there often is confusion when distinguishing the two. Teleology is the classical term for ethical theories that focus on outcomes, or ends, to determine correct ethical action. (Ferrell) Teleology comes from the Greek words “telos” meaning, “end” and “logos” meaning, science. Before Anscombe, utilitarianism was the more general term for ethical theories associated with teleology, focusing on the overall good created as the desired outcome. Today, consequentialism is the most widely accepted umbrella term, containing distinguishable sub-categories with a broadening of desired outcomes. To summarize concisely, consequentialism evaluates actions based solely on weighing the consequences of the action against a desired outcome.

- Types of Consequentialism

Consequentialism may be divided in different ways depending on how it is applied and the desired outcome. Many types of consequentialism do not have a formal name, and the variations we list below are not intended to be comprehensive. Our intent is to explore the most common forms of consequentialism, using the most widely accepted names for these forms. We can apply consequentialism to a decision by using its two forms: act consequentialism or rule consequentialism. Act consequentialism examines each act individually and determines the right act to be the one that produces the greatest number of consequences consistent with the desired outcome. (Frost) Rule consequentialism determines the morally right action to be the one that follows a rule whose observance would produce the desired outcome. (Sinott-Armstrong)

There are many desired outcomes. Two of the most widely known are: creating the most good for the most people – utilitarianism, and creating the most good for one’s self – egoism. We discuss utilitarianism in greater detail. Egoism is a selfish way to make ethical decisions, but some philosophers argue it truly is in everyone’s best interest for everyone to act in his or her own self interest (Shaw). To some degree everyone must act in her own self interest – the opposite extreme, altruism, means we act completely selflessly and only in the interest of others. The problem with altruism is that eventually, one who is completely selfless will have nothing left to give. Thus, the altruist destroys her ability to act in the interest of others.

- Strengths of consequentialism

We can apply consequentialism ubiquitously, because all decisions have measurable consequences. Deontology requires a rule to govern a decision, and not all decisions have a rule or duty associated with them. Virtue ethics examines a decision in the context of one’s character, but there is some debate as to what dispositions are virtues. We can apply consequentialism systematically. If we assign a numerical value to consequences, we can reach an ethical decision through mathematical evaluation. In summary, the biggest strengths of consequentialism are the relative ease of universal application and its usefulness for practical application.

- Problems with consequentialism

Despite its ease of universal application, applying consequentialist theory to a decision can be quite time-consuming and complicated in practice. In the ideal case, all consequences are identified and accounted. However, in almost all real decisions this is not possible. The process of identifying and weighing all the consequences, or even a number of consequences deemed sufficient to make the decision, is often too time consuming for decisions that need to be made quickly.

A second problem with applying consequentialism is observer or agent limitation. Once again the ideal case is a completely unbiased ethical agent weighing all possible consequences with equity and neutrality towards all affected parties. This godlike position is not attainable. No one person can know sufficient information about the consequences to make perfect judgments about a decision. In real world cases, observers are supposed to inform themselves as much as possible about the consequences to make the best judgment possible.

A third problem with consequentialism is dealing with actual and expected consequences. It is problematic to evaluate the morality of decision based on actual consequences as well as probable consequences. If an observer scales the weight of consequences based only on probability, some poor decisions can be made. A highly undesirable consequence may appear to be the result of a morally wrong decision. But to the decision maker, this consequence may be disregarded because it is highly improbable.

2. Utilitarianism

- Definition

Utilitarianism is a consequentialist moral theory focused on maximizing the overall good; the good of others as well as the good of one’s self. The notable thinkers associated with utilitarianism are Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill. These utilitarians are hedonistic, meaning, their ideas of good are associated with pleasure or happiness. (Driver) Thus, classical utilitarianism guides ethical decision makers to make decisions that bring the most pleasure for the greatest number of people. Utilitarianism is very closely associated with consequentialism, to the point where some use the terms interchangeably. Indeed, utilitarianism and consequentialism share many of the same tenets. One difference, however, is consequentialism does not specify a desired outcome, while utilitarianism specifies good as the desired outcome. For example, rule utilitarianism is the same as rule consequentialism except rule utilitarianism specifies that decisions should follow rules promoting the most good, instead of the more general assertion that rules should promote a certain desired outcome. To summarize with a concise definition: Utilitarianism is a consequentialist moral theory. Utilitarianism’s desired outcome the greatest amount of good possible.

- Problems with Utilitarianism Illustrated by Example

Utilitarianism as a sub-category of consequentialism means the theory has many of the same benefits and drawbacks. There are problems specific to utilitarianism. We illustrate examples of drawbacks with hypothetical situations.

First, utilitarianism can justify making decisions that violate a person’s human rights. What may be considered good for some people can violate rights of others. An example of this problem is a wealthy person who needs an organ transplant. If the wealthy person offers to donate a large sum of money to a charity to help thousands in exchange for being the top of the list for an organ transplant, utilitarianism says the wealthy person should be placed at the top of the list. Why? Because more good comes results from the wealthy person receiving the organ than would result if the next person on the list receives the organ. However, the next person on the list for the organ has the right to receive the organ first, and it seems unfair for the wealthy person to use her wealth as an advantage.

Another problem with utilitarianism is that it requires an impartial decision maker. Total impartiality does not allow special relationships like friends or family. The decision maker naturally considers the good of people close to her before more distant stakeholders. The celebrated train dilemma illustrates the impartiality problem. Suppose you can save a trainload of people heading for a collapsed bridge by pulling a switch to re-route the train. In doing so, your wife and children will certainly die because they are in the path of the train if it takes the alternate route. Many will not knowingly sacrifice their family for strangers. But utilitarianism forces the decision maker to weigh the overall good. Depending on the number of people on the train one may have to sacrifice the family.

A final criticism of utilitarianism is that it answers the question “what decision is right?” by answering “what decision brings about the most good, pleasure or happiness?” But the questions are not the same. It does not necessarily and logically follow the answer to one question will be the answer to the other. (Rachels) The argument is especially pertinent when applying act utilitarianism and thinking only of the consequences in the immediate future. For example, we can use utilitarianism to justify lying to another person to avoid immediate negative consequences of hurting feelings or damaging the relationship. But if no one ever provides truthful answers to tough questions adverse long-term consequences can result. The lie lead to further bad decisions made from ignorance or bad information, leading to far more dire consequences.

- Utilitarian Calculations

We apply utilitarian calculations on whether it is right to save a large private business from bankruptcy. These calculations are meant to illustrate the use of utilitarianism and are not comprehensive to the extent that all possible short and long-term consequences have been considered.

General Motors Bailout

Consider the bailout of General Motors (GM). Is it right to use government, i.e., taxpayers’ money to rescue a private corporation?

First, who are the primary stakeholders affected?

- Government

- Taxpayers

- GM

- Employees

- Shareholders

The secondary stakeholders are:

- Customers

- Suppliers

- Competitors

Second, examine the consequences for these stakeholders, and evaluate their significance.

- For government:

Negative consequences: generating a moral hazard. Large private companies will take on risk knowing the government will bail them out because they are perceived to be too large to fail. Without bankruptcy, firms will evaluate risk incorrectly.

Positive consequences: unemployment will not skyrocket in Michigan and its environs. Government will not have to pay unemployment benefits and there will not be a spiraling down effect on the economy.

- For taxpayers:

Negative consequences: Losing tax dollars that can be spent elsewhere. A probable consequence is a cut in spending on other government projects such as infrastructure or welfare.

The initial desired positive consequence: a stable business environment. The long-term desired consequences are stable to growing employment and a stronger economic community.

- For General Motors:

Positive consequences: the desired positive consequence for the bailout is to continue or even strengthen its business, avoid bankruptcy, and maintain the company’s reputation with customers. Although the bailout itself hurts the company’s reputation, an actual bankruptcy could be worse for its reputation among consumers.

Negative consequences: government control in GM’s operations and the required changes that are be painful and costly to make. However, a long-term consequence could be that the changes made would not be drastic enough. Even with the bailout, GM may go bankrupt in the future anyway.

- For employees:

Positive consequences: A very positive consequence for GM employees is that fewer people are laid off.

The same positive consequence applies to GM suppliers and their employees. Uninterrupted production means more business and job stability.

For competitors, the bailout would be short term negative, because they may gain more market share. Losing out on that extra market share also has negative consequences for the people who work for the competition such as lower wages resulting from lower sales.

Ultimately, we need to consider if the positive consequences are greater than the negative consequences. If the positive does outweigh the negative consequences, then we arrive at a decision that says it is ethical for government to bailout GM. That decision creates the most good or happiness for the greatest number of people.

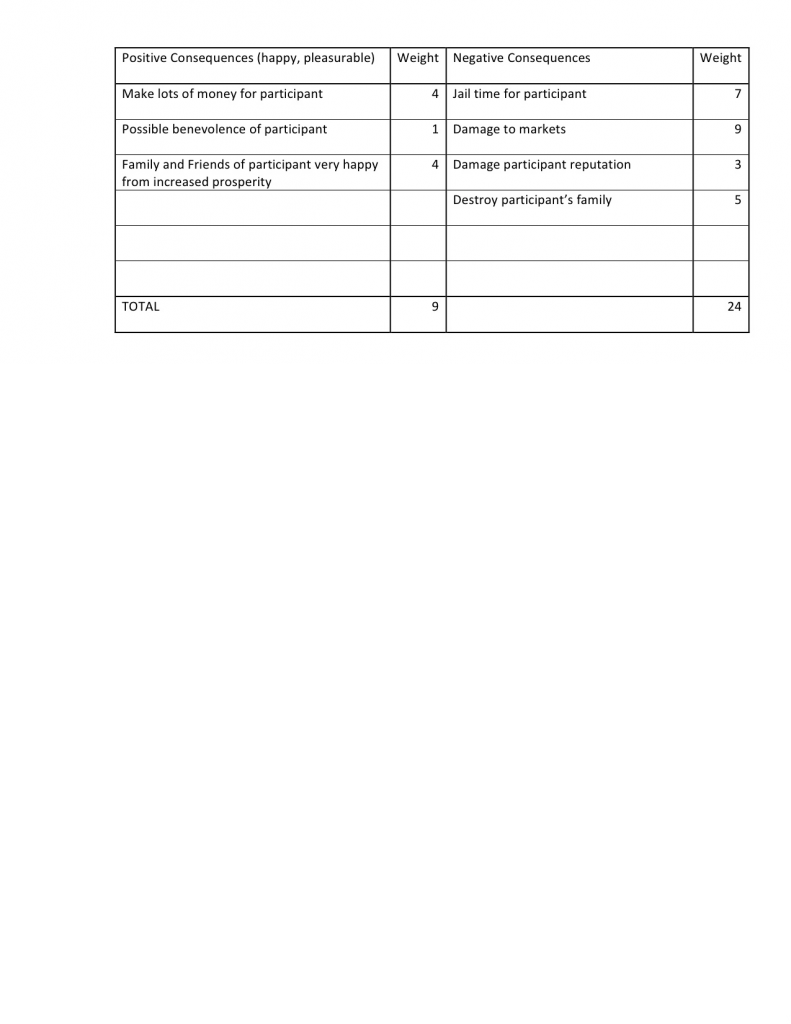

Numerical Example- Insider Trading

The second example is on insider trading. This example attempts to assign numerical weights to consequences to arrive at a decision. Recall, the principle driving utilitarianism is to choose the decision that leads to the most good for the greatest number. We need to examine the consequences for those affected either directly or indirectly.

The primary stakeholders in the decision on whether to commit insider trading is the person wanting to do insider trading (the tippee), the person who gives the insider information (the tipper), and the company about which they have the information. Secondary stakeholders are other investors in the market.

The primary purpose of insider trading is to make money for the insider involved. This is a huge positive consequence, especially when viewing the decision as an egoist. On the other hand, the insider may go to jail, not a pleasurable experience by any account. Another possible positive consequence is that those who get rich from insider trading will be benefactors to society through their philanthropy for instance.

For society at large, insider trading means trading unfairly through information not available to the market. This unfairness may cause people to stop participating in the market because the market is viewed as an unlevel playing field. If people do not participate in the market, the market will slowly wither. If the market suffers, capital formation and allocation also will suffer and in the longer term, the economy as a whole suffers. Applying some numbers in a table to help with the decision (weight scale 1-10):

Decision: To participate in insider trading or not (See Appendix 1)?

In this example, the total weight of positive consequences is much lower than the weight of the negative consequences, and thus the possible amount of happiness produced is greatly outweighed by the possible unhappiness- the decision should be to avoid participating in insider trading. From this utilitarian calculation, insider trading is unethical.

3. Conclusion

Consequentialism and utilitarianism are commonly used in decision making. It is natural and logical for a person to think of the consequences of their actions before acting. However, these ethical theories have their weaknesses and should perhaps be applied in combination with other normative ethical frameworks. In many cases, the ethical choices each theory recommends are the same.

By: Gerald Hart

Bibliography

- Frost, Martin. “Consequentialism.” Welcome Back to The Frost Blog. Web. 03 Nov. 2011. <http://www.martinfrost.ws/htmlfiles/consequentialism.html>.

- Driver, Julia. “The History of Utilitarianism.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 27 Mar. 2009. Web. 03 Nov. 2011. <http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/utilitarianism-history/>.

- Haynes, William. “Consequentialism.” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 24 Mar. 2006. Web. 03 Nov. 2011. <http://www.iep.utm.edu/conseque/>.

- Feiser, James. “Ethics .” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 29 June 2003. Web. 03 Nov. 2011. <http://www.iep.utm.edu/ethics/>.

- Ferrell, O.C., John Fraedrich, and Linda Ferrell. Business Ethics. 4th ed. Houhgton Mifflin. Photocopy.

- Rachels, Stuart, and James Rachels. The Elements of Moral Philosophy. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2010. Print.

- Shaw, William H. Business Ethics. Australia: Thomson Wadsworth, 2008. Photocopy.

- Sinott-Armstrong, Walter. “Consequentialism.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 20 May 2003. Web. 03 Nov. 2011. <http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/consequentialism/>.

Photos: Brizzle born and bred, Axel.Foley

APPENDIX 1