Some Solutions to Economic Inequality

The fourth in SPI’s series on Inequality

By: Remy Smith

For most families in the US, incomes are stagnating as real wages remain steady or are actually declining. Stagnating incomes mean that the “middle class is too weak to support the consumer spending that has historically driven our economic growth” (Stiglitz). Middle class households, “who are most likely to spend their incomes,” (Stiglitz) actually have lower incomes than they did in 1996, when adjusted for inflation. A strong middle class drives economic growth; however, today the middle class is pressed for money. This will lead to a consumer crisis in which aggregate demand will slump, as the middle class will not be able to purchase enough goods to sustain a thriving economy, and the affluent will not pick up the consumer slack (there is only so much one person could want to buy). Bottlenecking wealth limits economic prosperity, much like bottlenecking in biology limits a species’ evolutionary prospects.

Another element of wage stagnation is the loss of tax receipts. This prevents the federal government from implementing needed welfare programs or creating costly progressive policies. The government also cannot make “vital investments in infrastructure, education, research and health that are crucial for restoring long-term growth” (Stiglitz) without deficit financing. While viable, deficit spending is not politically feasible. Government spending is anathema to almost all Republicans. Many Democrats would also hurt their reelection chances by supporting new government spending programs. Unfortunately for many Americans, the creation of the Tea Party and fervent opposition to government spending comes at a time when additional governmental services are needed due to stagnating income.

Stagnant Wages

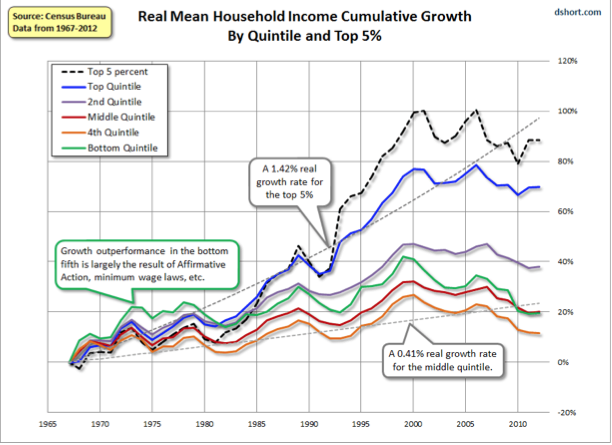

Wages have actually fallen for the lower and middle classes since the 1970s. The chart below was created using data from the US Census Bureau from 1967 through 2012. It shows wage growth for the five income quintiles and the top 5 percent of income earners. 1967 marks the beginning wage level, and each notch on the y-axis represents increments of 20 percent growth.

Figure 1

As made clear by the graph, the top 5 percent saw huge increases in income – almost 100 percent growth – whereas the fourth quintile experienced an annual growth rate of just 0.41 percent. Growth in the bottom quintile is largely attributed to redistributive policies, but even so, household income for the poorest Americans has increased just 20 percent since 1967. Most Americans are being excluded from the remarkable economic growth experienced by the elites within the top quintile.

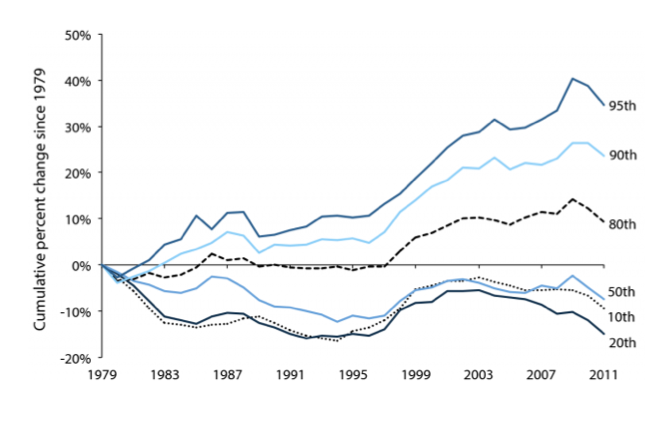

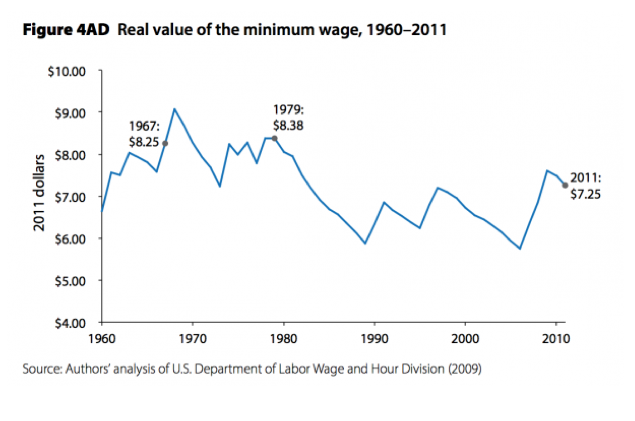

There’s more to the story, though. Altering the start year, we see the above graph is actually optimistic. The Economic Policy Institute compiled a graph (see figure 2) showing that since 1979, the income for the bottom fifth rose just 10.8 percent, and the middle fifth saw an increase of only 19.2 percent. Meanwhile, the incomes of the top 1 percent grew more than 240 percent over the same time period. This inequality can largely be explained by a decline in the real value of the minimum wage and the weakening of redistributive policies. During this time period, the wealthiest Americans saw their marginal tax rate fall dramatically, while the stock market, from which many of the most affluent make money, experienced historical gains.

Figure 2 (Source:Economic Policy Institute)

Figure 2 (Source:Economic Policy Institute)

Limiting the data to just men, the results are even more striking. A “typical male worker’s income in 2011 was lower than it was in 1968” by almost $1,000 (Stiglitz). Trends from the last two graphs continue here. In fact, wages for the 10th, 20th, and 50th percentiles of men actually fell between 1979 and 2011, and fell by a lot – up to 15 percent. The higher the wage percentile, the greater the wage gains (or lower the wage losses).

Figure 3 (Source:Economic Policy Institute)

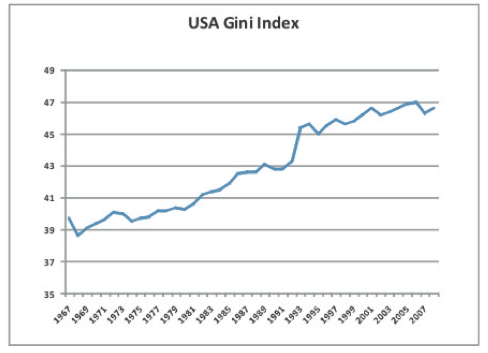

Increasing Inequality

Perhaps the most telling indicator of income inequality is the Gini index. The Gini index measures the income distribution of a nation. A Gini coefficient of zero implies perfect equality, meaning everyone has the same income. A coefficient of 1 describes perfect inequality, where one person has all available income and everyone else earns zero. This graph shows a steady increase in the US Gini index.

Figure 4 (Source:One Utah)

Clearly, there is growing inequality in wages, leading to inequalities in opportunity and the destruction of the middle class. But how did this come to be and what are some solutions to economic inequality?

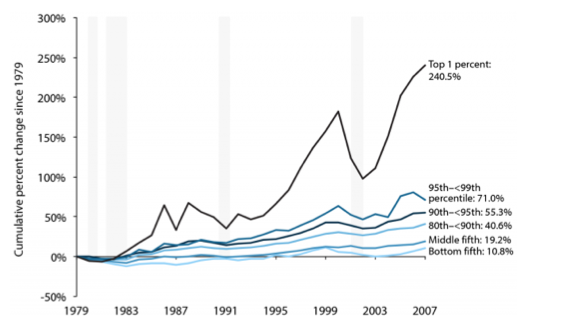

Minimum Wage

A major culprit of stagnant and declining wages for the lower quintiles is the declining value of the minimum wage. Upon inception, the minimum wage was not tied to inflation. Instead of increasing every year in tandem with the cost of living, the nominal value of the wage remains the same, so the real value falls. It takes an act of Congress to increase the minimum wage. Due to gridlock and politics, a minimum wage increase has happened rarely over the past four decades, leading to a decline in the real value of the minimum wage. The graph below depicts the real value of the minimum wage since 1960 (in 2011 dollars). Each uptick represents Congress raising the wage. Each decline is a period where inflation weakened the minimum wage value. The prolonged periods of decreasing value roughly match up with the decreases for the lowest quintile in the other graphs, demonstrating the importance of the minimum wage in determining wage values for the lowest income quintiles. Comparing the real value of the minimum wage to the Gini index graph, it is clear declining minimum wage directly corresponds to increased inequality. This is especially notable when looking at the data between 1980 and 1990 – an uninterrupted period of wage decline and a time of rapidly rising inequality.

Figure 5

Tax Cuts

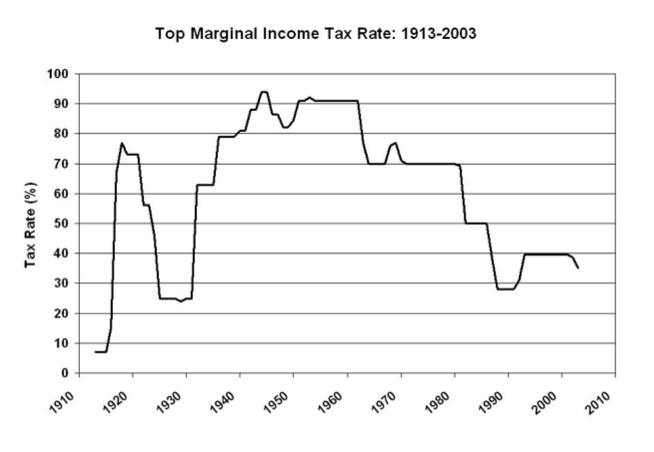

Another element behind growing inequality is the tax rate. The United States has a progressive income tax system, with the tax on one’s last dollar earned increasing as one’s income rises. In the 1950s, the top marginal tax rate on the wealthy was more than 90 percent, but it has since been drastically cut. High marginal tax rates on the rich allow for wealth redistribution and prevent inequality to the degree seen today. Such was the idea throughout presidential administrations in the 1940s, 50s and 60s.

Starting in the 1980s with Ronald Reagan, a wave of tax cuts took place, mostly benefitting high-income earners. The top rate fell to under 30 percent by 1990 and increased slightly under the Clinton administration, only to fall once more during the second Bush presidency.

Figure 6

The top 10 percent of income earners paid 71 percent of all federal income taxes in 2010, according to the Heritage Foundation. Our government relies on tax receipts from the wealthy to provide goods and services to others. Each marginal tax cut for the wealthy deprives the government of money. As mentioned before, a lack of money means the government cannot invest in its people, which is necessary to end inequality.

Of course there are many other contributing factors to the wild rise in income inequality, among them a decline in union membership, a resurgence in conservative ideology in politics, and huge stock market increases. The declining real value of the minimum wage and lower marginal tax rates for the wealthy, leading to decreases in government tax receipts, are two key factors.

Solutions

Income inequality is a problem, but it is a problem created by governance. It is not natural. That is the good news. If we created it, we can fix it. Progressive and enlightened policies can reverse the trends of the last three decades, increasing wage growth for the bottom income quintiles relative to wage growth for the top earners by raising the minimum wage to a livable level and raising top marginal tax rates. Expanding welfare rolls will also serve to curtail inequality and augment the purchasing power of the lower income earners. Long-term solutions can be crafted. Education is the most necessary investment to create economic sustainability and recreate class mobility.

- Raise the minimum wage.

Raising the minimum wage is the first step to reducing income inequality. Its sharp decline in real value means the lowest wage earners have no chance in keeping pace with those whose incomes are tied to the stock market or who have university degrees. Wages need to rise to a livable level.

Living wages take into account various costs an individual or family will encounter over the course of a year. These include food, childcare, healthcare, housing, transportation, and other necessities that vary by geographic location. Each city has a different living wage, data for which can be found on livingwage.mit.edu. Establishing a minimum wage fails to take into account any expenditures; it is simply a number that politicians and (some) economists find beneficial to low-income earners and society. The minimum wage needs to be tied to the living wage.

Since the living wage varies for each city, the federal government should make the minimum wage the lowest living wage of all cities for which data are available. The government also needs to mandate that each city adjust its minimum wage to equal the living wage and either tie it to inflation or necessitate that it change year by year based on rising prices of basic expenditures. Such a number likely will not differ much from President Obama’s proposal of $10.10 an hour and certainly will not be more than Seattle’s new minimum wage of $15 an hour. This will ensure no American will live in poverty and everyone will be able to afford the most basic needs.

The primary objection to raising the minimum wage or tying it to a living wage is the assertion that a higher value would increase unemployment. A recent CBO report found that raising the minimum wage could cost up to 500,000 jobs while increasing hourly wages for more than 16 million people. However, there is no economic consensus that raising the minimum wage necessarily leads to job loss.

Economist David Card examined a case in 1992, when New Jersey raised its minimum wage while Pennsylvania did not. Card found “the number of jobs actually went up in New Jersey…compared to the number of jobs in Pennsylvania” (Kestenbaum). The takeaway from this study is higher wages don’t necessary lead to unemployment. Higher wages can actually create employment by increasing the consumer power of low-income individuals, who will see an increase in wages and be able to spend more, thereby creating jobs.

Arindrajit Dube of the Brookings Institute asserts the decline in the real value of the minimum wage is a primary cause of income inequality and the best way to combat inequality is to raise the wage, adjusting as needed for cost of living. San Francisco provides a current case study. Until Seattle raised its minimum wage to $15 an hour, San Francisco had the highest minimum wage in the country. Unemployment actually dropped below 5 percent in San Francisco, whereas Oakland, located just across the Bay, maintained the federal minimum wage and faces unemployment of more than 8 percent. Raising the minimum wage has yet to demonstrably increase unemployment and be damaging to the economy.

Indeed, the government of Singapore, a nation that takes economic growth seriously, has overseen sustained increase in median income for Singaporeans over the last five years. Median monthly income from work of full-time employed citizens increased by 30 percent during the period. The technocratic government achieved this increase by public sector initiatives to raise incomes of low-wage workers. Yet, the unemployment rate of Singapore remains a low 1.9 percent.[i]

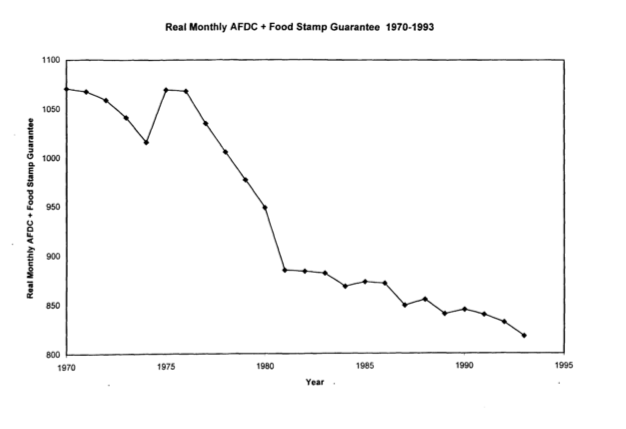

- Expand welfare benefits.

The chart below shows the decline in welfare benefits from 1970 through the 1990s. Compared with previous graphs, it’s easy to see the relationship between declining welfare benefits and increasing inequality.

Figure 7

Robert Moffitt, David Ribar, and Mark Wilhelm are the authors of an oft-cited study (from which the above graph is drawn) that concluded declining welfare benefits from the mid-1970s through the mid-1990s played a major role in the “increase in wage inequality in the labor market and the decline of real wages at the bottom of the distribution.”

The most important piece of welfare legislation is unemployment benefits. Those searching for a job need to receive benefits for the duration of their job hunt. In times of structural readjustment, older workers may struggle to find jobs. This is not necessarily their fault, and the argument they are “lazy” does not bear scrutiny. It falls to the government to make sure workers actively searching for jobs do not need to worry about poverty, foreclosure, and hunger. The government needs to care for its people, especially those seeking to become active members in America’s workforce.

Other welfare programs also need to be increased. Medicare and Medicaid need to be expanded to provide everyone with a basic degree of coverage. Medical expenses are rising much more rapidly than inflation, and many Americans are one illness or injury away from poverty – a talking line for many congressional Democrats. It is no far stretch or outrageous statement to say Americans deserve quality healthcare without risking poverty. Already hospitals cover the cost of the uninsured by charging the insured more. Studies show that insuring everyone will decrease costs for all.

Conservatives like to assert that welfare benefits cause “laziness” and complacency in life. They believe welfare actually inhibits individuals from pursuing better and higher-paying jobs. Is this proposition true? Studies find that only a few individuals are incentivized to curtail working hours because of welfare. This easing back largely occurs when benefits do not gradually decrease but rather end at a certain income level. An easy solution is for welfare benefits to decrease as income increases and to fade out after a certain level.

- Education

Raising the minimum wage and expanding welfare provide short-term solutions to income inequality. Sustainability, however, is found in education.

Failing to provide education directly perpetuates income inequality. During the Great Recession, those with a college degree faced an unemployment rate of around 5 percent, whereas those with less than a high school education saw unemployment rates reaching 15 percent.

Michael Spence, a Nobel Prize-winning economist, found that higher education leads to value-added jobs, which have higher incomes. Education begets higher wages, so education must be a priority to end rampant inequality. As Harvard’s Steven Strauss writes in the Huffington Post, the 2 percent unemployment amongst highly skilled workers in 2006 and 2007 is indicative of a skills shortage. Such a labor shortage leads to higher wages for the highly skilled. However, the many individuals who fail to achieve such skill levels enter fierce competition for low-skilled jobs, driving down wages and increasing inequality. Education solves this problem by turning out more highly skilled workers who will earn high wages.

Long-term economic growth and well-paying employment can be achieved by furthering education. The government, therefore, needs to provide accessible education. To do so, spending on education needs to increase. College tuition is rising quickly, turning away many lower-class and some middle-class students. These students will then earn lower wages, contributing to economically destabilizing wealth inequality, and will not be able to send their own children to college, furthering the dismal cycle. This cycle represents a market failure that requires government intervention. Doing so will provide professional jobs, economic growth, efficiency, innovation, and a natural distribution of income that will assure America economic stability and sustained growth for many years.

Governments should invest in higher education by covering tuition costs and living expenses for all students attending an accredited college or university. This will eliminate the main barrier – cost – to college attendance and ensure that all deserving students have an opportunity to further their education.

America can thrive again and create high-income jobs if it has a comparative advantage in education. We need to remain one of the world’s leading innovators in creating new technology and other jobs in burgeoning industries. Education will allow us to create wealth through new products and new creations. Education maintains the vibrancy and competitive edge in American industry.

Income inequality is a major problem in the United States. It poses a threat to long term sustainable economic recovery and prosperity. Wages are rapidly rising for the rich while they are stagnant – or even declining – for the poor. Economic inequality throughout society is increasing. A change is needed. Created by devaluing the minimum wage through a lack of action and unnecessary tax cuts for the rich, income inequality is a reversible trend. The minimum wage must be tied to the living wage to ensure that no working Americans live in poverty. Similarly, welfare benefits need to be expanded, namely unemployment benefits and medical care. These provide short-term solutions. Investing in education is necessary to create the types of jobs that will pay high wages for decades to come. Doing so will ease income inequality, as everyone has access to the institutions that enable workers to earn higher wages.

Voters need to recognize the importance of implementing such policies. In the end, it is the voters – the people – who have the final say in our elected officials and the course of action they take. Ending policies that create perpetual and increasing income inequality can be done, but it requires concerted action and agreement about what route is in the best interest of the nation.

http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/01/19/inequality-is-holding-back-the-recovery/

http://www.advisorperspectives.com/dshort/charts/census/household-incomes-growth-real-annotated.gif

http://www.epi.org/files/2012/charts-swa/2M.png.640

The State of Working America, 12th Edition (book by the Economic Policy Institute)

http://oneutah.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/gini_index.jpg

http://www.epi.org/publication/declining-federal-minimum-wage-inequality/

http://voteview.com/images/Top_Marginal_Income_Tax_Rate_1913-2003.jpg

http://www.heritage.org/federalbudget/top10-percent-income-earners

http://www.cbo.gov/publication/44995

http://www.npr.org/blogs/money/2014/03/06/286861541/does-raising-the-minimum-wage-kill-jobs

http://www.brookings.edu/research/papers/2014/06/19-minimum-wage-policy-state-local-levels-dube

http://www.nber.org/papers/w5774

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/steven-strauss/the-connection-between-ed_b_1066401.html

[i] Deutsche Bank Research, Asia Economics Monthly, 12 February 2015.

Editor: Angela Lutz

Picture: Google Images from www.usnews.com