Trans-Pacific Partnership: Common Good or Corporate Good?

By: Mark Anderson

There are a few issues on which liberals and conservatives agree. The idea that free trade has the potential to benefit all is one [1]. Free trade receives strong support from the American public, with over seventy percent of Americans reporting they believe free trade is good for the American economy [2]. So why then has there been such contentious debate over the Trans-Pacific Trade Agreement (TPP) despite the support for free trade? One answer is that TPP is less about free trade than managed trade, mostly to the advantage of corporate interest.

THE ECONOMICS OF FREE TRADE

Gains from Trade Based on Comparative Advantage and Specialization

In 1817, British stockbroker David Ricardo published his “The Principles of Political Economy [3].” In his treatise, Ricardo contested Adam Smith’s analysis of trade economics and conceived his own – Ricardo’s Theory of Comparative Advantage – which is admired by economists to this day [4]. Ricardo’s theory postulates two nations in autarky (a state of economic independence or virtually no free trade) can simultaneously achieve higher levels of wealth by engaging in free trade. According to Ricardo’s theory, each nation achieves this result by increasing production of the good(s) it has a comparative advantage in the production of and exporting those goods in exchange for the other good(s) in which they do not have a comparative advantage.

The concept of comparative advantage relies on the intuition of opportunity costs. An opportunity cost is any opportunity foregone when another alternative is chosen. To articulate an example, consider Jim, a member of the American labor force. If Jim works for an hour he can make a single car. If he works ten hours, he can knit a sweater. For Jim, the opportunity cost of creating one sweater is the ten cars he could have made instead (for simplicity, labor is the only factor of production considered in this example). If Jim wants one sweater and two cars, he will have to do twelve hours of work in total.

Li, Jim’s trading partner, is a member of the Chinese labor force. Since Li has access to the apparel industry’s leading technology, he makes a sweater in just one hour. Li does not know how to make cars though, so it would take him fifty hours just to produce one (he will have to read the entire “make-a-car instruction booklet.)

In autarky, the marginal cost of producing a car or sweater is the quantity of other goods that can be produced in the time it takes to produce one unit of cars or sweaters. For instance, Jim’s opportunity cost of producing one sweater is the ten cars he could have made in the ten hours. Jim’s opportunity cost of making a car is the 1/10th of a sweater he can make in an hour. For Li, the opportunity cost of producing a sweater is the 1/50th of an automobile he can produce in an hour, and the opportunity cost of producing an automobile is fifty sweaters. The argument affirmed in Ricardian theory is Li and Jim can both be better off by producing more of the good in which they have a comparative advantage, and then exporting that good in exchange for the other good where they lack comparative advantage. So if Jim wants one sweater to give his dad for Father’s day and Li wants a car to drive, both will be better off if Jim trades one of the cars he makes for one of Li’s sweaters than if they both produce the two goods independently. By specializing in the production of the good in which they have a comparative advantage and trading for the good which they do not, Li and Jim are both able to achieve higher levels of real income.

In this example, Li would export sweaters and Jim would export cars. Under free trade, Li is happy to exchange up to fifty of his sweaters in exchange for a single car. Meanwhile Jim is well served by trading up to ten cars for a single sweatshirt. The free trade price of a car will be less than fifty sweaters and greater than 1/10th of a sweater, and the free trade price of a sweater will be less than ten cars but greater than 1/50th of a car. At these relative prices, Li and Jim will both be better off as a result of free trade.

Jim and Li illustrate the gains from trade a nation attains by engaging in free trade based on comparative advantage. For example, if American workers have access to more advanced technology used to manufacture cars, but Chinese workers have access to more advanced technology used in the production of sweaters, American and Chinese workers face the same marginal productivities of labor as Jim and Li. Both nations become better off by partaking in free trade.

Empirical Evidence for Gains From Trade Based on Comparative Advantage

Example I: Gaza Strip and the West Bank

The gains from trade based on comparative advantage are most easily measured by comparing a nation’s real per-capita GDP in autarky and in free trade. If Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage holds true, a nation that moves from autarky to free trade should experience an increase in per-capita GDP.

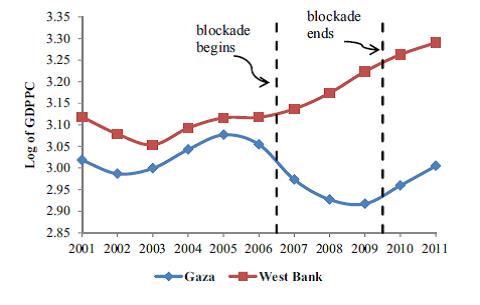

Though rare, there are several instances where a nation has undergone these changes in recent history. In “When trade stops: Lessons from the Gaza blockade 2007–2010,” Haggay Etkesa and Assaf Zimring examine the welfare consequences of an Israeli and Egyptian blockade on the Gaza Strip, which left the region in near autarky conditions [5].

Etkesa and Zimring write, “At the time the blockade began, the West Bank and Gaza had similar economic and political institutions, and, importantly, both before and after the blockade on Gaza, the two regions had very similar trends in prices and consumption.” Households in Gaza and the West Bank faced very similar economic conditions when both regions were exposed to free trade during the times before and after the blockade was put into place. By using the West Bank as a counterfactual economy for Gaza, Etkesa and Zimring compare GDP per-capita (GDPPC) in the two regions to measure the welfare consequences of Gaza’s autarky.

Their findings indicate the average welfare loss for households in the Gaza strip during the blockade was between fourteen and twenty-seven percent of pre-blockade expenditure value. Once the blockade was put into place, Etkesa and Zimring observe the production of manufactured goods, Gaza’s exporting industry, declined as production of services, previously Gaza’s importing industry, increased during the same time.

Example II: Japan’s Shift from Autarky

From the year 1639 till 1859, Japan maintained an isolationist policy. In the middle of the 1860s western nations intervened using military force to compel the Japanese shogun into abandoning his trade restrictions. Once exposed to free trade, Japanese firms could export goods like silk and tea which had a higher relative price in the global market than in the Japanese market (these two goods made up 35.9 and 28.2 percent of Japanese exports from 1868-1875, respectively). The result of Japan’s shift from autarky to free trade: Japan’s real income increased by up to 65 percent [6].

Gains from Trade Based on Market Competitiveness and Product Variety

Free trade affects the domestic economy by granting foreign firms access to domestic markets. This positively affects domestic markets by diminishing domestic firms’ market power in any monopolistically competitive industry. For example, consider a monopolistic or monopolistically competitive firm in the American sunglass industry. In the absence of free trade, this firm will curtail output and increase the price of sunglasses to levels below and above the competitive market equilibrium, respectively, in order to maximize its profits. If America allowed free trade of sunglasses, the domestic monopolist will no longer be able to control the domestic price of sunglasses by reducing outputs. The domestic monopolist will have to sell its glasses at market price. At any greater price consumers will simply elect to buy imported sunglasses from foreign firms.

Increased competition in domestic industry coupled with an increase in market size (as domestic firms may now sell their products to foreign consumers) has several favorable effects. Firstly, these changes cause inefficient firms with high costs of production to exit the market. Increased competition from foreign firms eliminates the most inefficient (and typically smallest) firms from the market, bolstering average efficiency of production. The number of domestic firms in the industry will decrease due to these inefficient firms exiting the industry. The total number of firms, however, increases due to the foreign firms that now have access to the domestic market.

If the U.S. and China were to move from autarky to free trade, the number of firms in the steel industry (for instance) decreases in both nations as the least efficient steel producing firms exit the market. Simultaneously, the average size of firms in the steel industry increases as a necessary consequence of inefficient firms leaving the market. This concept is fairly intuitive. For a given market size and demand for steel, when the number of firms selling steel decreases, each remaining firm must produce more steel so that overall industry output remains at the equilibrium level. In sum, the domestic industry becomes more efficient on average as the least efficient firms exit the market and the more efficient firms grow in size.

A third consequence of the U.S. and China enjoying free trade is that consumers gain access to a greater variety of goods. As mentioned previously, trade liberalization causes the number of domestic firms in a given industry to decrease, but causes the total number of firms in the industry to increase by allowing foreign firms to enter the market (the number of foreign firms that enter the market will be greater than the number of domestic firms that close down). A net increase in the number of firms in the market benefits consumers by allowing them to access a greater variety of goods. Going back to the U.S. and China example, consumers will now be able to choose between ten varieties or “brands” of domestically produced steel and ten types of Chinese steel. Previously consumers were able only to choose between fourteen varieties of domestically produced steel. The gains from increased product variety are even more sizeable in some industries. American consumers are better off when able to purchase four types of energy efficient cars, two sports cars, three minivans, or two motorcycles than when they may only choose between a van, a sports car, and a motorbike. Consumer utility is a nebulous concept and consequentially it is hard to measure the gains attributable to increased product variety. Though difficult to quantify, these effects are still palpable and relevant.

Empirical Evidence for Gains from Trade Based on Market Competitiveness and Product Variety

Example I: Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement

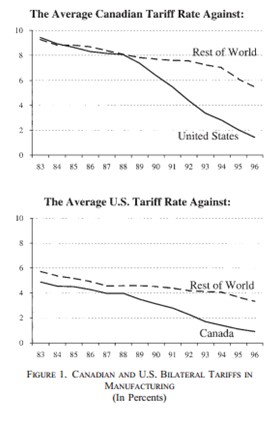

On January 1st of 1989, the United States and Canada signed a free trade agreement (FTA) which, significantly reduced barriers to foreign trade and investment between the two nations. With the FTA in place, industries subject to the largest tariff reductions (typically low-end manufacturing industries) experienced an astounding seventeen percent increase in labor productivity.

Industries that experienced the greatest Canadian tariff cuts saw plant-level labor productivity rise by twelve percent, while industries that experienced the largest U.S. tariff cuts enjoyed a fourteen percent increase in labor productivity. Trefler writes that half of these increases in productivity can be attributed to inefficent high cost firms contracting or exiting the market. The total number of firms in industries most affected by the tariff reductions also went down by eight percent due to inefficient firms leaving the market [7].

Free Trade and Employment

Opponents of free trade argue that free trade harms domestic employment by exposing domestic industry to “unfair competition” from foreign countries, often with fewer labor protection laws and lower minimum wages. While this may be the case in some industries over specified periods of time, there is almost no relationship between unemployment and free trade in the long run.

The misconception that free trade generates unemployment is pertinent to the comparative advantage example involving Jim and Li. Rather than examine two individuals though, say Jim and Li’s production possibilities represent the quantities of cars and sweaters America or China could produce with an hour of labor. When the two nations engage in free trade, America will produce more cars and less sweaters than under autarky. Consequently, employment increases in the automobile industry and decreases in the sweater industry. While this shift may cause some unemployment in the short term as laborers move from the sweater to the car industry, aggregate employment is unaffected by free trade longer term.

Empirical Evidence on Free Trade and Unemployment

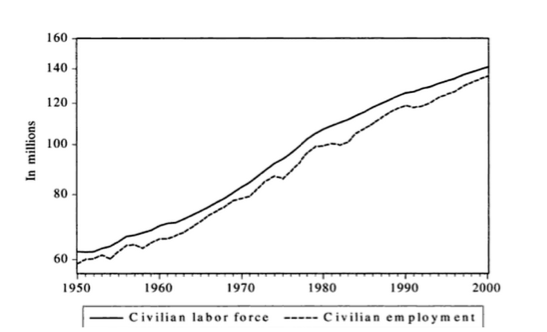

In the long run, it appears that the number of unemployed Americans is a function of the total size of the American population. The following chart suggests unemployment in the U.S. bears no significant relation to the nation’s exposure to free trade. Economist Douglas Irwin adds there is always some unemployment, which is represented by the difference between the two series on the graph. Irwin also adds the overall effect of free trade on unemployment in an economy is null, and the business cycle, demographics, and labor market policies dictate the rate of unemployment. This is why we see unemployment increase in 1980’s and early 1990’s due to an economic recession, but not respond to changes in trade policy that occurred during the same period.

While this evidence is not consistent with claims of free trade opponents that free trade increases unemployment, it refutes free trade proponents’ claim that free trade curtails unemployment. Opponents point to industries where free trade harms employment rather than noting aggregated changes in unemployment. Proponents do the opposite, focusing on industries where free trade reduces unemployment rather than the aggregated figures [8].

Empirical Evidence on Free Trade and Unemployment: Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement

Going back to the Canada-U.S. FTA example, we also can use employment statistics from the time before and after the policy was implemented to analyze the relationship between unemployment and free trade liberalization. After the FTA was put into effect, manufacturing experienced a five percent reduction in employment, a three percent decrease in output, and the number of manufacturing firms decreased by four percent [9]. While these short-run adjustment costs are sizeable, they diminished quickly, as manufacturing unemployment and output have rebounded since 1996. Meanwhile, the long-run gains from free trade are larger and benefit all economies involved for as long as they remain in effect.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement – what it is, how it will affect the American and global economies, and whether it should be adopted

Economic theory and empirical analysis affirm free trade can be a net-benefit for all nations involved. Free trade may be generally appreciated as a means of attaining higher levels of economic welfare. Yet, this does not necessarily mean trade agreements like the Trans-Pacific Partnership are desirable.

“This is not a trade agreement…David Ricardo is irrelevant” writes American Economist Paul Krugman on the TPP. While trade agreements of old strengthened the American economy as postulated by Ricardian theory, TPP opponents like Krugman argue the United States has already achieved such a high level of economic integration that further efforts to increase trade liberalization will hardly have any effect. For example, in 1995 when the average tariff on imported goods was roughly 3.3%, the welfare gain from trade liberalization was expected to be a 0.38% increase in GDP. By 2013, the average import tariff in the U.S. dropped to around 1.3%, and the expected welfare gain from trade liberalization fell to a small fraction of its 1995 value – an estimated 0.01% increase in GDP, or 1/38th of the projected gains from 1995 [10]. Japan’s conversion from virtual autarky to free trade resulted in a sizeable increase in per-capita GDP. In contrast, TPP will have a very marginal, almost negligible effect on the American economy.

What Does the TPP Contain?

Even if the TPP marginally benefits Americans, why has it aroused such stark opposition? First, we do not know what the deal contains because the government has yet to reveal text of the TPP to the public. Why the opacity? Senator Elizabeth Warren says, “We can’t make this deal public because if the American people saw what was in it, they would be opposed to it.” Thankfully, several members of congress have spoken about the deal, and a few chapters of the classified trade agreement have even been published by WikiLeaks.

Only 5 of 29 Chapters of TPP are about Trade

First, of the 29 chapters of the TPP, only 5 are about trade. Julian Assange, editor-in-chief of WikiLeaks reports:

“The others are about regulating the Internet and what Internet—Internet service providers have to collect information. They have to hand it over to companies under certain circumstances. It’s about regulating labor, what labor conditions can be applied, regulating, whether you can favor local industry, regulating the hospital healthcare system, privatization of hospitals [12].”

In other words, the remaining twenty-four chapters of the TPP cater to corporate interests. For instance, the Intellectual Property chapter of the TPP includes provisions that sacrifice internet freedoms in favor of corporate copyright protections. Specifically, the trade agreement compels internet services providers to block access to websites that violate copyrights, require they terminate service to customers with multiple allegations of copyright infringement, filter all internet content for copyright-infringing materials, and most concerning of all, forces internet providers to disclose copyright-infringing customer identities [13].

Environment: Corporations can Sue Governments

The Environmental chapter of the TPP sings a similar tune. This portion gives corporations the ability to sue governments – domestic and foreign – for enacting public interest legislation that may reduce corporate profits. This public interest legislation that corporations can challenge in court include environmental regulations and industrial efficiency standards [14]. Presidential candidate and Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders gives another example of what the TPP would allow “If a country or a state wants to protect its kids from tobacco and smoking, they could be taken to an international tribunal because they’re threatening the future profits of Phillip Morris [15].”

Corporations Helped Formulate TPP Policy

How did these corporate-empowering segments, unrelated to free trade, find their way into the TPP? While the terms of the agreement are withheld from the public, corporations not only get to see the details – they actually helped formulate the policy.

“Of the 566 committee members, 306 come from private industry and an additional 174 hail from trade associations. All told they represent 85% of the voices on the trade committees. They attend private meetings with administration officials and get access to documents that the public cannot see [16].”

Meanwhile, only 31 labor representatives are on the TPP committee. The overwhelmingly pro-corporate TPP is no coincidence; it is legislation written by corporations, for corporations.

Ethical Analysis

The TPP is hard to defend from a utilitarian perspective. It was written by and is intended to benefit the wealthiest members of society at the expense of the common good. The intellectual property chapter, for example, extends copyrights on brand name drugs, restricting millions of poor impoverished people from accessing live-saving drugs and treatments [17]. The deal prioritizes corporate profits, some would say, even over human lives. The other provisions embrace the same methodology, sacrificing internet freedoms to aid corporate profit, preventing environmental regulations that might harm corporate profits. The keynote of the so-called “trade agreement” is taking from those with the least and giving more to the few who already have too much. It seems inconceivable the TPP would maximize welfare among the people it affects. Thus, a utilitarian will disapprove TPP.

The TPP doesn’t fair well from a deontological perspective either. Americans emphasize freedom and democracy as moral law. Our nation and its political figures have a moral obligation to protect these values. But the TPP does the opposite. The secrecy of the deal makes it inherently undemocratic. The Senate’s vote to “fast track” Trade Promotion Authority on June 23rd, gave the President power to bring trade legislation to congress to vote on, but denies congress the ability to negotiate, amend, of filibuster the trade deal. This move is similarly undemocratic [18]. The unjustifiably pro-corporate trade policy will remain unjustifiably pro-corporate.

“The Trans-Pacific Partnership is a disastrous trade agreement designed to protect the interests of the largest multi-national corporations at the expense of workers, consumers, the environment and the foundations of American democracy. It will also negatively impact some of the poorest people in the world.”

-Bernie Sanders

-x-

[1] (http://www.cato.org/blog/super-majority-economists-agree-trade-barriers-should-go).

[2] Irwin, Douglas A. Free Trade Under Fire (Third Edition), Princeton University Press, 2009.

[3] Irwin (2009)

[4] Irwin, (2009)

[5] (https://www.dropbox.com/s/dwg4wt081yni2km/gaza_paper_jie.pdf?dl=0).

[6] Irwin (2009)

[7] http://www-2.rotman.utoronto.ca/~dtrefler/papers/Trefler_AER_2004.pdf

[8] Irwin, (2009)

[9] http://www.nber.org/papers/w8293.pdf

[10] (https://webspace.princeton.edu/users/pkrugman/krugman_nabe.pdf

[11] http://elizabethwarren.com/blog/you-cant-read-this

[12] http://www.democracynow.org/2015/5/27/julian_assange_on_the_trans_pacific

[13] (https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2012/08/tpp-creates-liabilities-isps-and-put-your-rights-risk

[14] http://action.sierraclub.org/site/DocServer/0584_TPP_Report_03_low.pdf?docID=14641

[15] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eY–mT28Jk8

[17] http://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/article/tpp-trade-deal-will-be-devastating-access-affordable-medicines

[18] http://www.dailydot.com/politics/senate-trade-promotion-authority-campaign-donations/

Photo: Courtesy of www.citizen.org