Financing, Ethics, and the Brazilian Olympics

INTRODUCTION

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, will host the 2016 Olympics, a first for any South American country. In 2014, they will also hold the FIFA (Federation Internationale de Football Association) 2014 World Cup. Commitments to these mega-events mean that both the country and city of Rio de Janeiro have a lot of work to do before they are prepared and meet both FIFA and International Olympic Committee (IOC) standards. A mega-event is a large-scale cultural event that holds significant international importance and attracts tourism.[1] Both events have the potential to encourage growth of the country if structured properly and finances are allocated appropriately; mega-events can also negatively burden a host country in a number of ways. Brazil is unique in having the opportunity of hosting both events back to back. The hope is that these events will contribute to Brazil’s growth as an emerging economy and significant financial investments will continue to benefit the country post-Olympics.

While the citizens are excited about the Olympics, there are concerns about the large number of infrastructure projects and the expenses required in Rio. This case study explains Brazil’s current situation, details financing for the 2016 games, analyzes past financial issues with Olympics, and evaluates the socio-economic impact on citizens from an ethical viewpoint. The allocation of funds and resources for such improvements can be controversial, especially when plans get delayed and end up over budget. Publications focusing on implications of past Olympics, along with personal field research conducted in the summer of 2010 are utilized.[2] The focus will remain on the Olympics in 2016, however the 2014 World Cup will also be discussed due to the close time proximity in which these events will occur.

BRAZIL

Goldman Sachs named Brazil one of the four fastest growing economies in 2001 as part of their BRIC fund.[3] Brazil has experienced significant growth and development in the last decade. The country was affected by the latest global economic downturn, but it was one of the last countries to experience recession and the first to recover. Brazil is slightly larger than the United States, and is very rich in natural resources. The country leads South America and Latin America in terms of growth and economic status, and is currently among the 10th largest economies in the world. In the past, extreme poverty and income inequality plagued the country; today, the middle class is beginning to expand, thus decreasing the large disparity of wealth.[4]

In addition to economic growth and increased status as a world power, Brazil was granted the FIFA 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Summer Olympic Games. Preparation for these mega-events has begun; both will require a large amount of investment from the private and public sectors. Olympic events have varying impacts on countries. Barcelona is the example of success in hosting the Olympics, but Greece demonstrates how a country can also end up in debt and fall short in preparation. The ambitions of hosting these events may not be conducive to achieving the continued growth for which Brazil is hoping. Studies indicate that, “in developing countries, the economic impact by the Games is smaller than in industrialized countries.”[5] From interviews conducted in my field research, some interviewees expressed concern about hosting both events consecutively and following through with both successfully.[6] Brazilians are optimistic that these events will bring tourism, employment and strengthen the economy. Often to offset the financial burdens of a mega-event, governments promise to clean up corruption and fix social problems. The nod to host the Olympics, is representative of the progress that the country has made. However, acting as a host city cannot be seen as the cure-all for social and economic problems that currently hinder the country.

There is no doubt the World Cup and the Olympics will provide temporary jobs, increase tourism and influence foreign investment. Citizens anticipate an increase in job opportunities with the need for manual labor for building Olympic infrastructure. Research projects the increase in tourism and foreign investment will mainly impact the wealthy. Historically, “development is highly uneven and tends to benefit private developers and construction interests while creating spaces of leisure for wealthy residents and the international tourist class.” [7] The PAC (Federal Governments Plan for Accelerated Growth) satisfies the regulations of the mega-events by bringing social development to poor areas, but this comes at a cost of increased security. Planning and organizing is key in allowing the country to fully benefit from the mega-events. “There is an absolute necessity to consistently plan, to maximize the positives, and neutralize the negatives.”[8] Unfortunately, it has taken an Olympic Bid and World Cup to finally motivate much needed spending on infrastructure and security improvements.

Brazilians are skeptical about the government’s proposed urban reforms. The city of Rio underwent reform before the 2007 Pan American Games (Pan Am Games); the positive impacts were only temporary. The changes for the Pan Am games, “never resolved the issue of social control entirely; instead they merely introduced a new set of antagonisms and changed the contours of the struggle between those who were benefitting from the new Rio and those who were not.”[9] Brazilians hope that the impacts of the Olympics and large investments will be permanent, but historically, the government has not completed projects as promised.

OLYMPIC GAMES

The media has consistently quoted a large multiplier effect for the 2016 Olympics. A report by Haddad and Haddad calculated a 4.26 multiplier.[10] Projecting that for every $1 USD invested, $3.26 will be generated until 2027, or $51.1 USD billon. Often times the use of multipliers to indicate economic benefit is exaggerated; this seems to be the case for 2016. Tommy Andersson states that multipliers are often inflated 10-90 per cent.[11] Total economic impact of mega-events is difficult to measure and there are a number of studies with varying numbers. On average, the economic impacts of Olympic Games are under $10 billion.[12] The expenditure seen in Table 2 of the appendix indicates an estimate of 16.6 Billion USD in spending alone. The inflated numbers projected to the general public about total expected outcome may only disappoint Brazilians. Much profit received in terms of profits does not go back to the public, is goes to shareholders and investors. Public funding is sacrificed to host mega-events; increased taxes and spending cuts in other areas are not taken into account.

Barcelona is consistently quoted as the gold medal winner in terms of Olympic hosting successes, but many host countries have not been impacted like Barcelona. Montreal in 1976 and Athens in 2004 are examples of games that have left the host countries with large financial debts. The financial status of Greece is the center stage of the Eurozone. One-fourth of their current budget deficit was spent on the Olympics. While blame cannot be solely placed on hosting the Olympics, the events may have contributed to the country’s financial woes.

Many of the facilities built for the Greek Games, are currently sitting unutilized, yet use public funds for maintenance and operation.[13] The 2000 Games in Sydney have a similar story, underutilized stadiums and facilities are still costing $40 Million USD a year, as of 2009.[14] The use, or lack thereof, of facilities for post-mega-events is troubling. Brazil hosted the 2007 Pan American Games, which actually helped Brazil secure the Olympic Bid. However, facilities built for the Pan Am Games took large amounts of funds from Federal Workers Fund among other public programs, and are sitting empty. Some of the buildings were even built on wetlands, sank, and required additional investment to save the building. A few of the Olympic Stadiums and venues are to be built on the same wetlands, due to lack of available space in the city. This shows a lack of consideration of where facilities are located and further the ignorance of post-Olympic usability. Other high-cost stadiums sit empty, but are not up to Olympics standards, thus requiring further investment for 2016.[15] In all these cases the governments uses public funding from taxpayers to build arenas that do not benefit the public after the games. Obviously the expected outcomes of continuous inflow of money for Athens and Greece were not enough to provide funds for post-game upkeep. Questioning where public funds for Olympics would have gone, is valid. Funding for the Olympics can be validated to a certain extent with tourism, international attention and prestige. It can even be argued that a mega-event is the only motivation that some governments have to invest in infrastructure. The difficulty is deciding when the amount of public funding negatively impacts taxpayers.

Analyzing what Barcelona did differently from Montreal is difficult. Both cities made significant investments in infrastructure. In fact, all non-United States games after Montreal made large investments in infrastructure. As with all other host-countries, Brazil hopes to be a ‘Barcelona,’ but the key to success is finding the right formula. Infrastructure is important, but proper planning and exact execution seem to be where countries come up short. Mega-events are exciting and are something Brazilians are pleased to be apart of, but the expected long-term benefits of the infrastructure, social, and economic projects are problematic.

OLYMPIC PROJECTS

Infrastructure

The IOC initially had doubts that the city of Rio had infrastructure capabilities to host the games. Security was a huge concern. A description of infrastructure projects demonstrates the extent of work required before 2016. The long-term impact of such projects is contingent on proper and complete execution of these plans. Public Olympic Authority (APO), an extra-governmental organization, has the power of allocating US$15 million to improve infrastructure.[16] A theme of the 2016 Olympics in Rio is development acceleration. The details of how the development will be carried out have not been clearly defined.[17] To increase social standards and infrastructure the PAC has guaranteed an additional sum of money to accomplish and meet IOC expectations.

It is estimated that today, Rio would only be able to house 52,000 tourists; the expected number is 1 million. There is a massive need for housing, and transportation development. To cover housing issues, the port in Rio will dock an estimated six cruise ships to meet accommodation requirements.[18] To house these ships however, the port must also be revamped. Hotel accommodations will also be upgraded. Increases in occupancy will be useful during the Olympics, but as with other host cities the extra capacity will likely not be utilized after the event. In an effort to ease transportation demands, an estimated US$5 billon is allocated for transportation. The plan includes an extended subway to suburban Rio de Janeiro, an expansion of the current subway. The Olympic Village is not in the city center so the government will have to renovate transportation facilities.

Both airports in Rio, along with four other nationwide airports will undergo remodeling for the World Cup and Olympics. The traffic to and from the airport is planned to improve with more shuttles and bus routes. Traffic in Rio de Janeiro is congested during most hours of the day. The Bid for 2016 also provides details on the following: upgrades to meet technology requirements, satisfying IOC regulatory demands, increasing the work force, a solid marketing campaign, additional standards for the Paralympics, and many other details of the planning process. Proper completion of these projects has two positive outcomes: it will aid in the overall success of the event and will also lead to future lasting benefits for the community.[19]

Security

The IOC has serious concerns about overcrowding, crime, and drug trafficking in the favelas.[20] The government must now clean up these areas to make them suitable for the crowds of Olympic spectators. Thus, Rio is on a timeline to make many improvements before 2016. In an effort to prepare for the Olympic bid, twelve projects have been initiated to improve the quality of the police force, with an emphasis on training and increasing task forces.

In addition to increasing the quality of police forces, another method used by the Brazilians to reduce crime is making international headlines with the invasion of favelas.[21] To understand the complexities of security in these areas, one must understand the definition of a favela. The census conducted in 2000 by the IBGE (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatistica) defines a favela as an aglomerado subnormal (sub-normal agglomerate). To be classified, as an aglomerado subnormal an area must have the following: more than 51 houses in an area and the majority of houses lack land title or official land documentation. In less official terms, favelas are slums in Brazil and are generally considered squatter settlements. The same census in 2000 indicated the state of Rio de Janeiro has 811 favelas; when the 2010 census is accessible, it is probable these figures will increase.

Part of the security funding for Rio, is allotted to increase police numbers and raise salaries. This funding is necessary to employ the UPP (Unidade de Polícia Pacificadora) and other special forces known as the BOPE (Batalhão de Operações Policiais Especiais).[22] In favelas without UPP’s, the drug traffickers serve as a form of a police force to enforce control and order in the community. Favela residents originally occupied land that was not theirs because the residents could not afford housing. Now, favelas are a part of Brazilian society and culture, but unfortunately also are a source of violence and drug trafficking. The UPP serves to pacify or control favelas, where police currently have no authority. Eighteen favelas are now under UPP’s power. By the 2016 Olympics these units will run all major favelas in Zona Sul (the south zone) of Rio de Janeiro. Rocinha, where I conducted research, arguably the largest favela in Brazil, was just occupied in November.

The process of pacification is complicated and violent. From various interviews, here is a collected summary of the process.[23] A favela is targeted and scheduled for pacification on a day unknown to the public. BOPE invades the favela, usually in the very early morning around 5 a.m. This force has already mapped and targeted houses they are going to raid. Generally the most powerful drug traffickers live toward the top of the hill of the favela, and the BOPE begins there. In the early morning invasion the BOPE opens fire and usually kills a select group they believe are the most powerful traffickers of the area. The next few days are violent, full of gunfire and hundreds of police occupy and control the surrounding area. Citizens avoid leaving their homes, so they are not victim to stray bullets. The BOPE works day and night to arrest and clear the community of traffickers. Once they believe most are jailed, dead or fled, then the UPP takes over to pacify the favela. The UPP works to maintain peace in the community to keep the pacified favela free of trafficking. The UPP works on a more personal level with the community to gain trust and enact social change. This type of police task force use favela citizens as UPP police. This method of policing is significantly different from a traditional force. The end goal is for favela citizens to enjoy community security without traffickers controlling the neighborhood.[24]

The ethics of the pacification process is not depends on the methods used in the pacification process. Innocent civilians are sometimes killed in the invasion process and the raid is violent. The BOPE has been the subject of criticism from Amnesty International and other human rights activist groups because of the police to civilian death ratio during raid and other encounters. In one view, greatest good is created, if drug trafficking is considerably decreased or eliminated. The process of pacification is not just or fair, does not demonstrate virtue in action, and violates right to life, privacy and security. While previous pacifications were fatal, the most recent pacification of Rocinha, was less violent due to pressures from various organizations. If pacification continues without high levels of violence, then the process would be more ethical by helping people and creating a better environment for society.

Governing bodies argue that the high number of deaths is warranted because they see no other option to fixing the historic problem of the favela. They justify their actions by contending their duty is to protect tourists and the larger number of citizens outside the favela. While the tourists may be safe during the Olympics and the World Cup, the preparation leading to the mega-events comes at an expense Brazilians. Costs include loss of direct benefits of tax funding social programs, potential rises in taxes and human rights violations. There has been no other solution to date that has been effective in “securing” favelas. According to utilitarianism only the consequences of an action matter in the ethical calculation. The greatest good for the greatest number is what counts. Therefore, the current method of pacification of favelas is ethical from a utilitarian viewpoint.

Financing

Preparing the Bid for the 2016 Olympics required a report on how Brazil was to finance the event. In the Finance section of the Candidature File, Brazil reports they allocated USD $240 billon for the Olympics. These funds are from the PAC. The PAC has provided much needed infrastructure, ecological conversation, educational developments, and social programs for the poor among other positive developments. Before the bid was granted, the government had “allocated” funds away from a very successful project that had positive impacts for Brazilians. The Federal, State and City governments guarantee the following: (1) finance and fund the OCOG (Organizing Committee of the Olympic Games) and non-OCOG budget, (2) cover any potential economic shortfalls of the OCOG, and (3) cover refunds of IOC (International Olympic Committee) advance payments or other IOC contributions to the OCOG.[25] To most successful use funding it is suggested:

The Rio 2016 Olympic Committee’s adherence to the sustainability concept, coupled with the proven public partnership concept will decrease the risk of marginal cost. Alternative spending on education and other public infrastructure is just another possible destination for funding, but economic forecasts hope that such change will also be brought about by the games.[26]

Before Brazil was granted the Olympics, the government had to guarantee financial backing. If the games are over budget, don’t received expected financial outcomes, or have unexpected financial burdens, the Brazilian government has complete fiduciary responsibility.

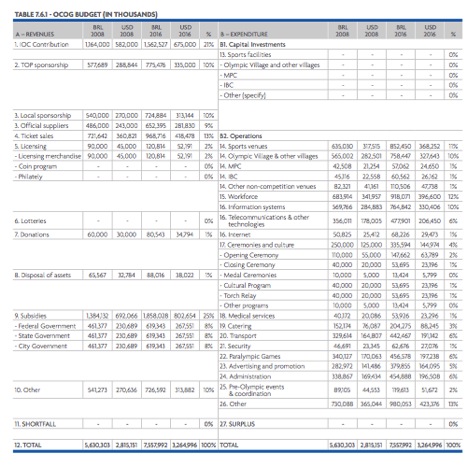

Table 1 and Table 2 in the appendix are excerpts from the Candidature File. Table 1 shows TOP Sponsorship around 10%. This number is realistic, as investment from TOP Sponsorships are ones such as Coca-Cola, McDonald’s etc. who make significant contributions. The Federal, State and Local Government account for 25% of funding. However, if any of the categories fall short, these “subsidies” will be required to make up the difference. The non-OCOG Budget for periphery projects such as infrastructure, security, medical and other investments are expensed at 3.7 million USD. These projects are more permanent projects for city infrastructure, except for the sports villages and venues. Proper implementation of these projects has the largest potential to do the most good for the citizens.

The file also shows a timeline of how much the government and other bodies will be spending per year. According to this, they don’t expect to spend any more funds on the Olympics after 2016. Sydney, Australia probably did not anticipate sending more money on the Olympics four years after the events. The Olympic projects are already behind schedule. Not keeping to a schedule usually means increases in cost. The Pan American Games was 10 times over its original budget.[27] This was a much lower-scale event. If the Brazilian Games were to go 10 times over budget, the impact on taxpayers will be enormous.

ETHICS

How much spending of federal, state and local public funding is the right amount for a mega-event such as the Olympics? There is not going to be a clear-cut answer and number to this question. Besides expectations of financial revenues, world attraction and hopes to spur future tourism, benefits for taxpaying citizens comes from long-term infrastructure projects. The proper implementation and use of funds with completion of infrastructure projects is crucial in order for citizens to receive benefits from hosting the Olympics. If the IOC remains sustainable in following through with post-Olympic plans while maintaining the permanent infrastructure projects, the events will be worth the time and investment. The greater amount of benefit experienced by citizens will increase the justification for hosting the events.

If all the infrastructure projects are successfully and completely installed, the benefits are numerous. Access to the subway by a greater number of people, especially those in low income groups may allow for more job and educational opportunities that were previously difficult to reach without transportation accessibility. The subway also reduces the number of automobiles and pollution on the streets. The work in airports is also necessary for the growing city even without the Olympics. Smaller aesthetic projects that clean up waterways and parks promote environmental awareness. Ecological efforts are nearly always positive. An increase in the number of jobs is good for the unemployed and for the economy. However the increases may be merely temporary. The increases in housing is only positive in the event that post-Olympics, the accommodations are converted to condominiums for permanent residence. Housing is an issue in the city. The investments in security, if UPP continues to be funded after 2016, have potential to change the face of Brazil. The historical impact of violent favelas will be altered. Poor residents will have better opportunities, in a safe environment, without the adverse influence of drug trafficking.

CONCLUSION

The Olympic Organizing Committee has the responsibility to make decisions that do not infringe on citizens’ rights. Spending too much of taxpayers’ money on the event, so that social programs lose funding, would infringe on people’s rights. Governing bodies and committees have fiduciary duties to allocate taxpayers’ money in a responsible manner. Hosting an Olympics game does not usually help in upholding these duties because these events generally benefit the few. Federal funds are also being directed at one city in the country instead of being spread out around the country.

The Olympics will only be worthwhile if the games create a form of benefit or advance for Brazilian society as a whole. This goal relies on the government and committees to fully keep their promises. A large increase in tourism and an inflow of profits have the potential of being advantageous to some Brazilians. A more achievable result is stable infrastructure. As seen with the Pan American Games, promises on budgets and facilities post-events were not met. For the large amount of public financing that is being channeled into mega-events to be ethical, the money spent must have benefits for Brazil’s citizens. Proper implementation and allocation of time and resources will help achieve social improvement goals and promises. Brazil may not continue to see tourism and profits from the Olympics post-2016, but hopefully the infrastructure and security investments will be worthwhile. The most ethically justifiable reason for hosting an Olympics is positive results from infrastructure and security investments. It is a hope that these infrastructure investments will continue to serve the city and encourage post-Olympic tourism. Given the projected spending and in view of past profits gained by other host countries, a net positive benefit from hosting an Olympics in Brazil will likely be difficult to achieve.

BY: ERIN ELEANOR SHERIDAN

APPENDIX

Table 1.

Numbers in Thousands. 2016 Numbers are projects considering inflation. Exchange rate is 2 BRL=1 USD

Table 2:

Numbers in Thousands. 2016 Numbers are projects considering inflation. Exchange rate is 2 BRL=1 USD

[1] Christopher Gaffney, “Mega-Events and Socio-Spatial Dynamics in Rio de Janeiro, 1919-2016,” Journal of Latin American Geography 9, no. 1 (2010).

[3] Goldman Sachs, “BRIC Fund,” in Financials (2010).

[4] The World Bank Group, “Brazil Country Brief,” (World Bank 2010). http://go.worldbank.org/C7LQJLFV30

[5] Gaffney, “Mega-Events and Socio-Spatial Dynamics in Rio de Janeiro, 1919-2016.”; ibid.

[6] Erin E. Sheridan, “UPP: Field Research in Rio de Janeiro Brazil ” (August 2010).

[7] Barbara Schausteck de Almeida, Fernando Marinho Mezzadri, and Wanderley Marchi Junior, “Condsideracoes Sociaisa e Simbolicas sobre sedes de Megaeventos Esportivos,” MotrivivÍncia Ano XXI, no. 32-33 (Jun-Dez 2009).178-192.

[8] Barbara ibid. Translation form Portuguese to English.

[9] Quoted in, Christopher Gaffney, “Mega-events and socio-spatial dynamics.”

[10] Eduardo A. Haddad, and Paulo R Hahhad, “Major sport events and regional development: the case of Rio de Janeiro 2016 Olympics Games,” Regional Science Policy & Practice 2, no. 1 (July 2010).

[11] Tommy D. Andersson, John Armbrect, and Erik Lundberg, “Impact of Mega-Events on the Economy,” Asian Business & Management (2008). http://www.palgrave-journals.com.www2.lib.ku.edu:2048/abm/index.html.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Derek Gatopoulos, “Greek Financial Crisis: Did 2004 Athens Olympics Spark Problems In Greece?,” Huffingtonpost.com, 06/03/2010 2010. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2010/06/03/greek-financial-crisis-olympics_n_598829.html.

[14] Benjamin McGuirk Wagar, “Marginal Benefits of Hosting the Summer Olympics: Focusing on the BRIC National Brazil (Rio 2016),” DigitalCommons@Providence (2009). 5.

[15] Gaffney, “Mega-Events and Socio-Spatial Dynamics in Rio de Janeiro, 1919-2016.”, 20.

[16]Brazilian Olympic Brazilian Olympic Committee, “Candidature File for Rio de Janeiro to Host the 2016 Olympic and Paraolympic Games,” Ministerio do Esporte (2009).,

[17] Gaffney Gaffney, “Mega-Events and Socio-Spatial Dynamics in Rio de Janeiro, 1919-2016.”

[18] Sheridan, “UPP: Field Research in Rio de Janeiro Brazil “.Unpublished Research.

[19] Brazilian Olympic Committee, “Candidature File for Rio de Janeiro to Host the 2016 Olympic and Paraolympic Games,” Finance, no. 7 (2009).

[20] Brazilian Olympic Committee, “Candidature File for Rio de Janeiro to Host the 2016 Olympic and Paraolympic Games.”

[21] IBGE, “Censo 2000,” (2000), ftp://ftp.ibge.gov.br/Censos/Censo_Demografico_2000/Dados_do_Universo/.

[22] A book written about the BOPE and turned into an internationally accredited film, Tropa de Elite (Elite Squad).

[23] Erin Sheridan, “UPP: Field Research in Rio de Janeiro Brazil “.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Brazilian Olympic Committee, “Candidature File for Rio de Janeiro to Host the 2016 Olympic and Paraolympic Games.”

[26] Wagar, “Marginal Benefits of Hosting the Summer Olympics: Focusing on the BRIC National Brazil (Rio 2016).”

[27] Gaffney, “Mega-Events and Socio-Spatial Dynamics in Rio de Janeiro, 1919-2016.”

Bibliography

Andersson, Tommy D., John Armbrect, and Erik Lundberg. “Impact of Mega-Events on the Economy.” Asian Business & Management (2008): 163-79. http://www.palgrave-journals.com.www2.lib.ku.edu:2048/abm/index.html.

Brazilian Olympic Committee. “Candidature File for Rio De Janeiro to Host the 2016 Olympic and Paraolympic Games.” Ministerio do Esporte (2009).

———. “Candidature File for Rio De Janeiro to Host the 2016 Olympic and Paraolympic Games.” Finance, no. 7 (2009 2009): 114-35.

Gaffney, Christopher. “Mega-Events and Socio-Spatial Dynamics in Rio De Janeiro, 1919-2016.” Journal of Latin American Geography 9, no. 1 (2010): 21.

Gatopoulos, Derek. “Greek Financial Crisis: Did 2004 Athens Olympics Spark Problems in Greece?” Huffingtonpost.com, 06/03/2010 2010. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2010/06/03/greek-financial-crisis-olympics_n_598829.html.

Haddad, Eduardo A., and Paulo R Hahhad. “Major Sport Events and Regional Development: The Case of Rio De Janeiro 2016 Olympics Games.” In, Regional Science Policy & Practice 2, no. 1 (July 2010): 80-99.

IBGE. “Censo 2000.” In, (2000). ftp://ftp.ibge.gov.br/Censos/Censo_Demografico_2000/Dados_do_Universo/.

Sachs, Goldman. “Bric Fund.” In Financials, 2010.

Schausteck de Almeida, Barbara, Fernando Marinho Mezzadri, and Wanderley Marchi Junior. “Condsideracoes Sociaisa E Simbolicas Sobre Sedes De Megaeventos Esportivos.” MotrivivÍncia Ano XXI, no. 32-33 (Jun-Dez 2009): 178-92.

Sheridan, Erin E. . “Upp: Field Research in Rio De Janeiro Brazil “, August 2010.

The World Bank Group. “Brazil Country Brief.” World Bank 2010.

Wagar, Benjamin McGuirk. “Marginal Benefits of Hosting the Summer Olympics: Focusing on the Bric National Brazil (Rio 2016).” DigitalCommons@Providence (10/1/2009 2009): 12.

Photo: www.flickr.com/photos/maewest/3205101172/in/photostream/